Freya Gowrley

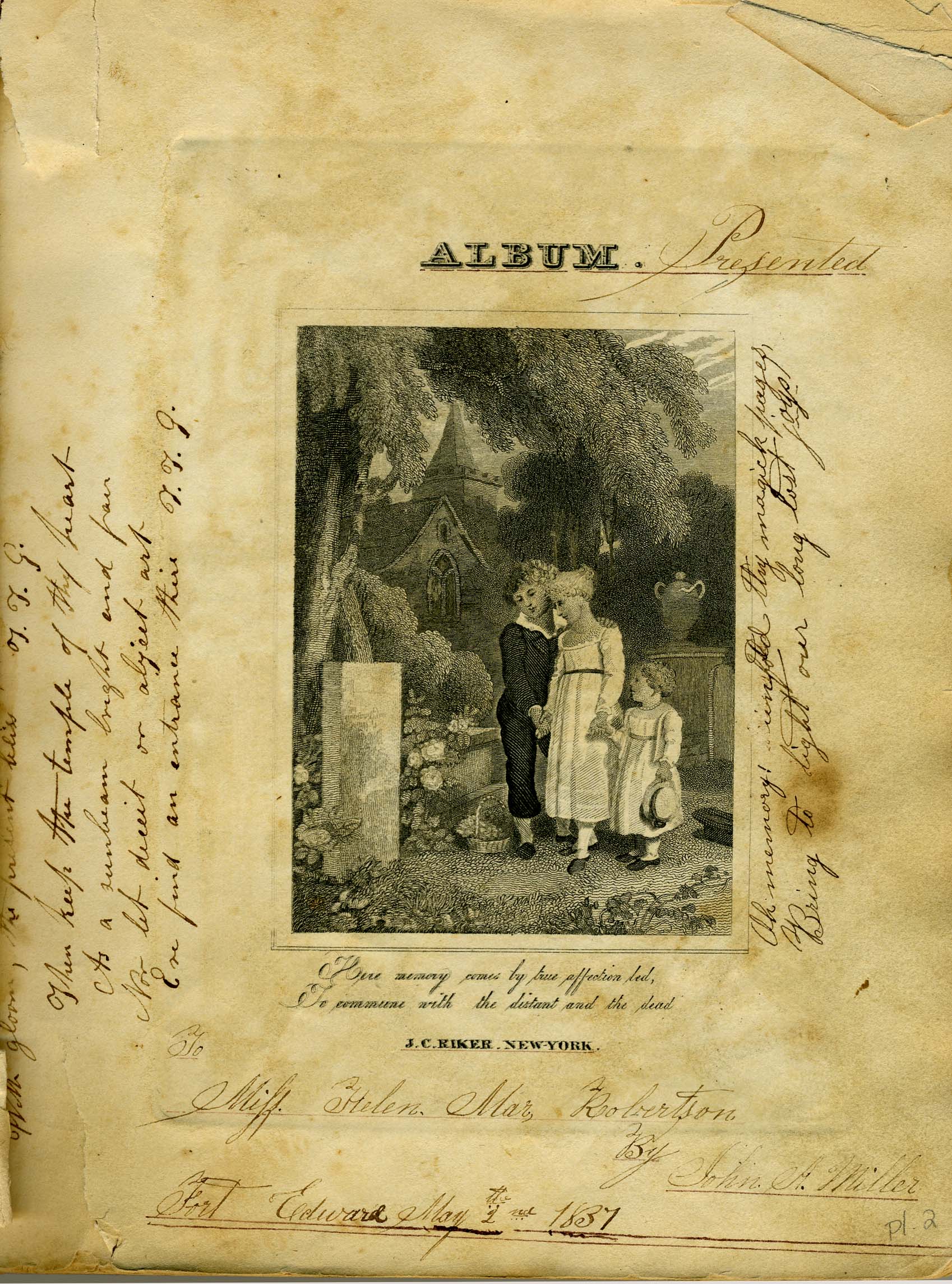

Between 1837 and 1852, an “Album” of poetry and personal sentiments was compiled for a woman named Helen Mar Robertson, who lived near Fort Edward, New York. Housed in a mass-produced volume, around quarto size, and labelled “Album” on its spine, the volume was published and sold by J. C. Riker in New York. In addition to its many blank pages—now filled with handwritten effusions of love and affection—the Album came with several engravings depicting both European and North American landscapes. Two of these inclusions are accompanied by hand-drawn illustrations of flowers, and another page features a drawing of a woman in profile, identified as “Ellen Terry.”[1]

In many ways the characteristics of Robertson’s album as outlined above are typical of the genre discussed in this article, that of the “sentimental album,” a term I employ to denote any album whose sentimental function seems to be the primary motivation behind its construction. Yet to talk about a “typical” sentimental album is something of a misnomer. As the preface to Robertson’s own volume declares:

an album is a book destined to preserve the autographs of friends and acquaintances, and in a word, to reflect the thoughts, feelings, and passions of those who engrave them on its pages. Who then dare anticipate the future contents of this book! Its sentiment, its tone, and its talent, all will be different, almost every page will bear the imprints of a different character—what an emblem of our own minds!

The passage highlights the fact that it is the very plurality, complexity and multi-vocality of this media that characterizes its production.

Indeed, such albums were made by both men and women, young and old; they could be compiled by the album’s owner, or friends or family on their behalf; and individuals might own or create several examples over their lifetimes. Produced at a time when emotional expression often found material form in Britain and America, sentimental albums commemorate deeply personal feelings of joy or sorrow, yet we often know very little about their owners beyond their names and where they lived, which is the case for all of the albums discussed in this article.[2]

Albums’ material qualities are similarly varied. They could be hand-made or purchased from a publisher, and although usually around quarto size, they can be much smaller than this. Bound in leather, albums might be black, brown, navy, magenta or bottle green in color, and their covers often feature gold tooling, perhaps with the word “Album” on the front or spine. Their contributions range from the textual to the visual to the material, with anything from poetic couplets, prose, locks of hair, cuttings from plants, drawings and collaged paper added to their pages. Even the terminology we use to describe such volumes is inherently mutable–depending on the institutional repository in which they are held, they might variously be labelled as albums, commonplace books or even scrapbooks, making it hard to discuss such volumes as a discrete form of artistic practice.[3] As a result, album culture is often absent from histories of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century visual and material culture, despite its ubiquity during this time.

Reflexivity

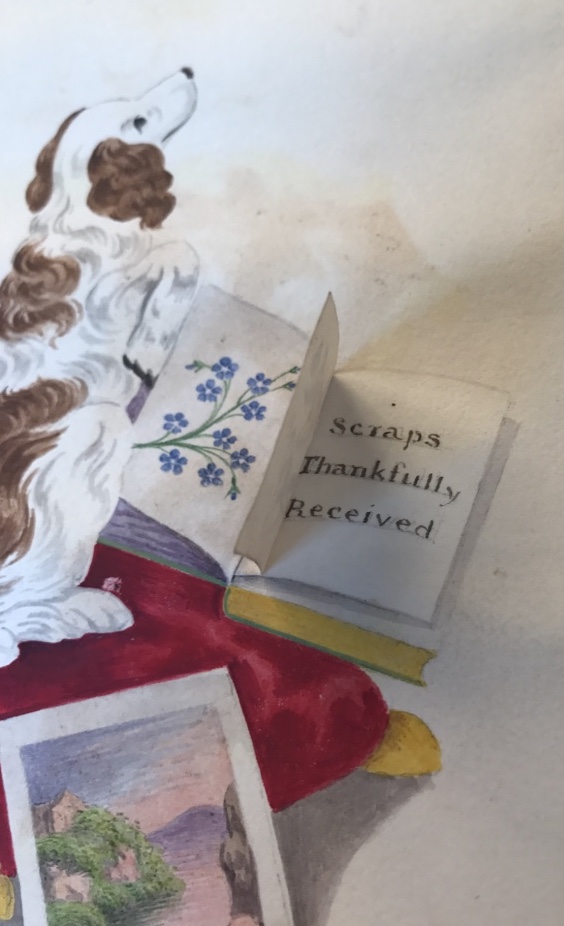

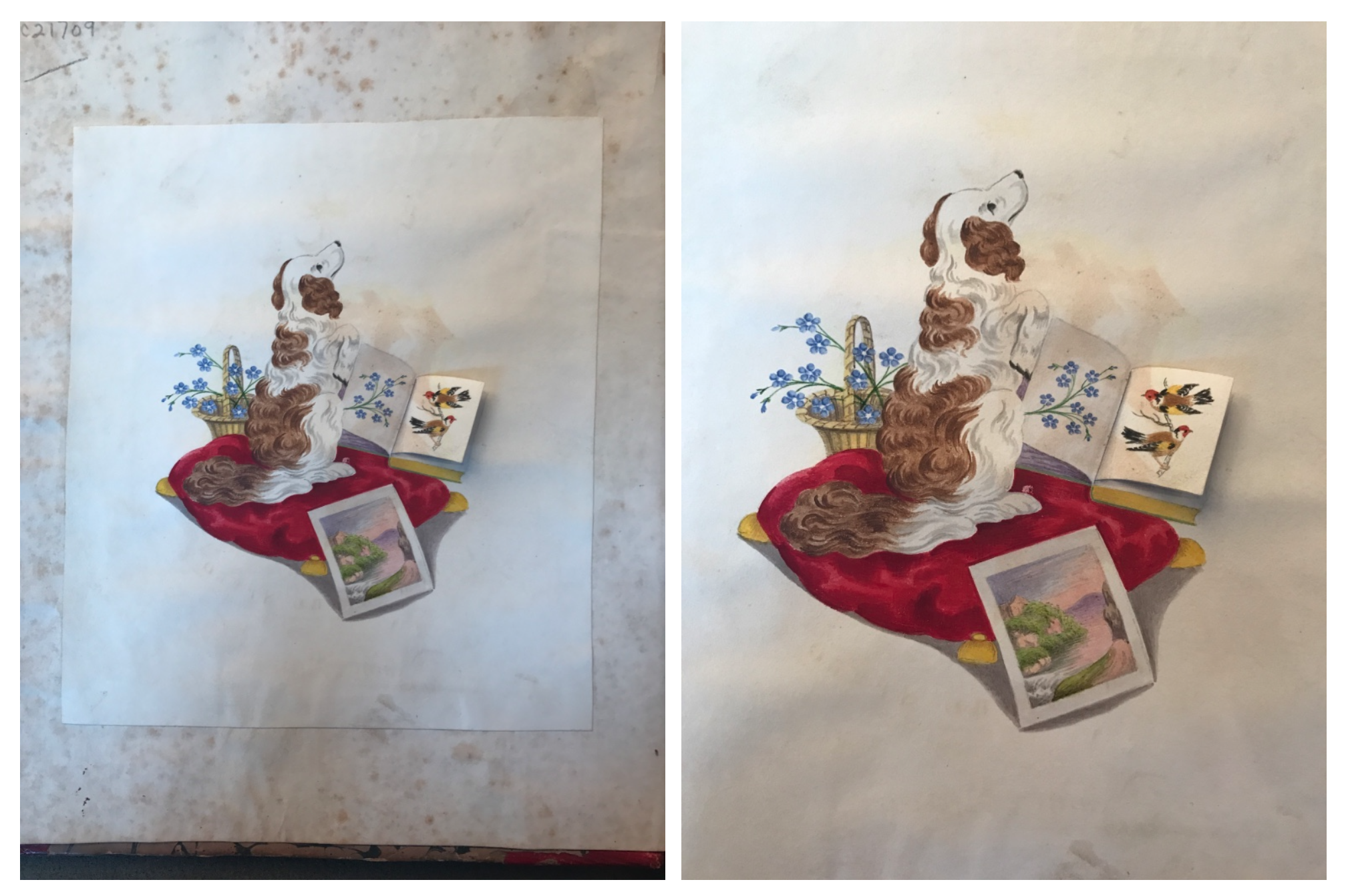

LEFT: Fig. 1. John Hearne, Commonplace Book, 1820. Watercolor, 26cm. PN6245.H43 C66. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. Photograph by the author.

RIGHT: Fig. 2. Detail of Fig 1.

An example of the type of album described above is the Commonplace Book of a man named John Hearne, dating from around 1820, which opens with a hand-drawn, hand-made frontispiece in which a spaniel begs for scraps (Figs. 1 and 2). An example of witty linguistic play, the frontispiece imitates those of commercially-sold albums produced on both sides of the Atlantic in this period.[4] The “scraps” here are of course two-fold, denoting, firstly, the culinary remains that might be offered to a canine companion at the end of a meal, and secondly, a more unusual kind of material donation. Rather than begging for food, here the supplicating spaniel asks for a different type of scrap: cuttings clipped from a branch of forget-me-nots and drawings pulled from a sketch-book, which wait to be transposed into a new volume. Closer attention to the depicted album reveals that its right-hand page is in fact a movable flap, beneath which reads “Scraps Thankfully Received” (Fig. 3). Like the depicted spaniel, then, the frontispiece itself functions to request scraps from those into whose hands the book might fall. As a culmination of representation and reality, this turnable album page—an album within an album—is a characteristic example of the genre’s reflexivity, a knowing reference to the typical forms and functions of sentimental albums during the early nineteenth century.

Like the spectral meal to which its punning refers, the dog’s begging also invokes the exchange of sociable objects and images that characterized and comprised such volumes. Although the title “commonplace book” (a term often used to denote a manuscript compiled from extracts of published texts) suggests an introspective and even private volume, in fact Hearne’s book is more similar to what we might traditionally consider as a sentimental album: an inherently variable volume made from a range of visual, material, and literary contributions by many hands. The scraps that the dog and, by extension, the album itself begs to receive therefore highlight the sentimental album’s collective and collected nature. Slippery nomenclature aside, Hearne’s is a prototypical album, a complex manuscript featuring scrappy donations from a range of friends and relatives, including collaged inclusions, textual excerpts, and paper fragments that were given to Hearne by a range of donors. These donations were not merely aesthetic inclusions, however, but deeply emotional gestures that testified to and materialized the affective bonds between album-owner and album-contributor. The reflexivity of these designs, then, does not merely provide a meditation of the specific materiality and medium of the album as a form, but is rather an active reflection upon how that materiality could construct and sustain relationships.

This article unpacks the correlation between the fabrication of sentimental albums and the creation of intimacy in early nineteenth-century Britain and North America, focusing on the reflexive gestures made by such albums. In so doing, it extends Christina Lupton’s ideas of reflexivity outlined in Knowing Books: The Consciousness of Mediation in Eighteenth-Century Britain (2012), in which she defined literary reflexivity as the way that eighteenth-century texts were written “so as to suggest that they have […] a sentience that emanates from their material form in print and announces itself as a knowledge of the relationship between an author, narrator and audience.”[5] Just as Lupton identified and discussed an array of material texts that used “a wide variety of discursive tricks” to “appear cognizant of how they are made,” including the use of language “to project their text’s physical form as print, paper, and commodity, and to make texts able to register their physical origins, movement, and arrival, in a reader’s hand,” this essay examines albums’ knowing references to their very materiality, their typical characteristics, and the physical and intellectual processes through which they were made.[6]

Building on the existing scholarly literature on albums, which firmly demonstrates their social and emotional character, I explore connections between the emotional self and the album’s physical self.[7] Examining how albums expressed these sentimental functions, I argue that they self-consciously employed a kind of medium specificity that deliberately drew on their own characteristics, and which was in turn crucial to how the genre allowed multitudinous owners, authors, and viewers to reflect on their affective ties. By examining a number of previously unpublished albums produced in Britain and North America between 1800 and 1860 from the holdings of the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library as well as the Yale Center for British Art, I focus on how the covers, frontispieces, dedications, and poetic inclusions of these volumes actively expressed their affective natures. By unpacking these reflective and reflexive visual, material, and textual gestures over the first half of the nineteenth century, I ultimately show how such gestures constructed album and album-maker alike.

Self-Conscious Objects

In her seminal work on Victorian women’s albums, Patrizia di Bello defines the genre in terms of its etymological origins, with its name taken from the Latin albus, meaning white, and the Roman albo, meaning blank.[8] This description can be nuanced and elaborated on by paying attention to albums themselves. As is typical of their reflexive makeup, such volumes often included definitions and musings on their own proper form and character, particularly in an early, and therefore appropriately introductory, part of the book. For example, Helen S. Grover’s mid-nineteenth-century “Album of Beauty,” made in New York, opens with an extensive meditation on the album’s function. Written by the contributor “William” in 1857, it is worth quoting at length:

An album is intended to receive the literary contributions of friends […]

Each inscribes a few lines expressive of the estimation in which the possessor of the album is held. Of course, there will be as great a variety of expression as there are writers; but fulsome adulation and insecurity should never be found. Good judgement, as well as affection should dictate every word: the blending of these will produce words, that will be a truthful expression of the real feeling of the writer. Let every word of praise that be written herein be true; every hope and wish that here finds place, sincere. As you from time to time read over these memorials, may you be cheered with the thought that these are the words of your friends who are ready—as far as in their lines—to make life’s pathway pleasant.

The apostle Paul commends to our regard, Love & Virtue, Purity & Justice, Truth & Honor; all of these I am sure you possess, and to each and all I dedicate your album.[9]

William’s dedication reinforces the album’s inherently social nature, identifying it as a repository for the writings of friends, whilst emphasizing the importance of purity and truth in its various contributions. The text also stresses the enduring emotional significance of such writings, speaking of the album-owner’s eventual reading and re-reading of the manuscript. In this way, the dedication also speaks to the temporality of the manuscript album, formed, like friendship itself, over a period of months and years. The dedication therefore serves to address both the album’s owner and its future contributors, who are to heed William’s advice as they compose affectionate and sincere works for its pages.

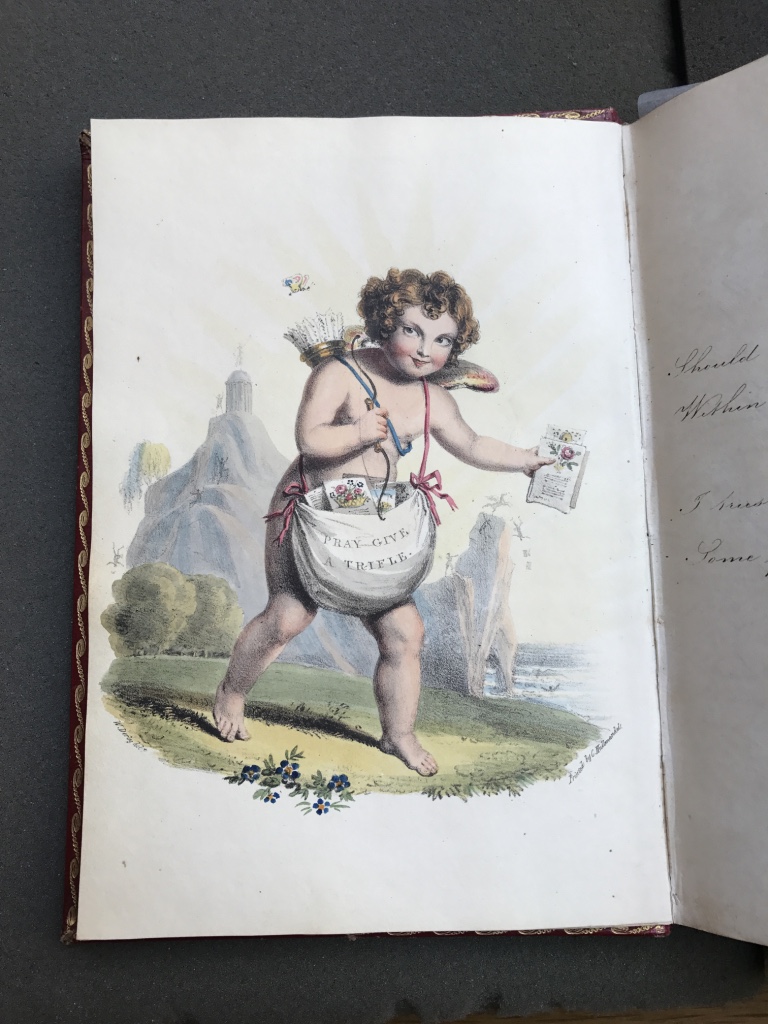

Fig. 4. Catharine Muriel, Commonplace Book, 1824-1835. Engraving, 23cm. PN6245.M87 C66 1833. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. Photograph by the author.

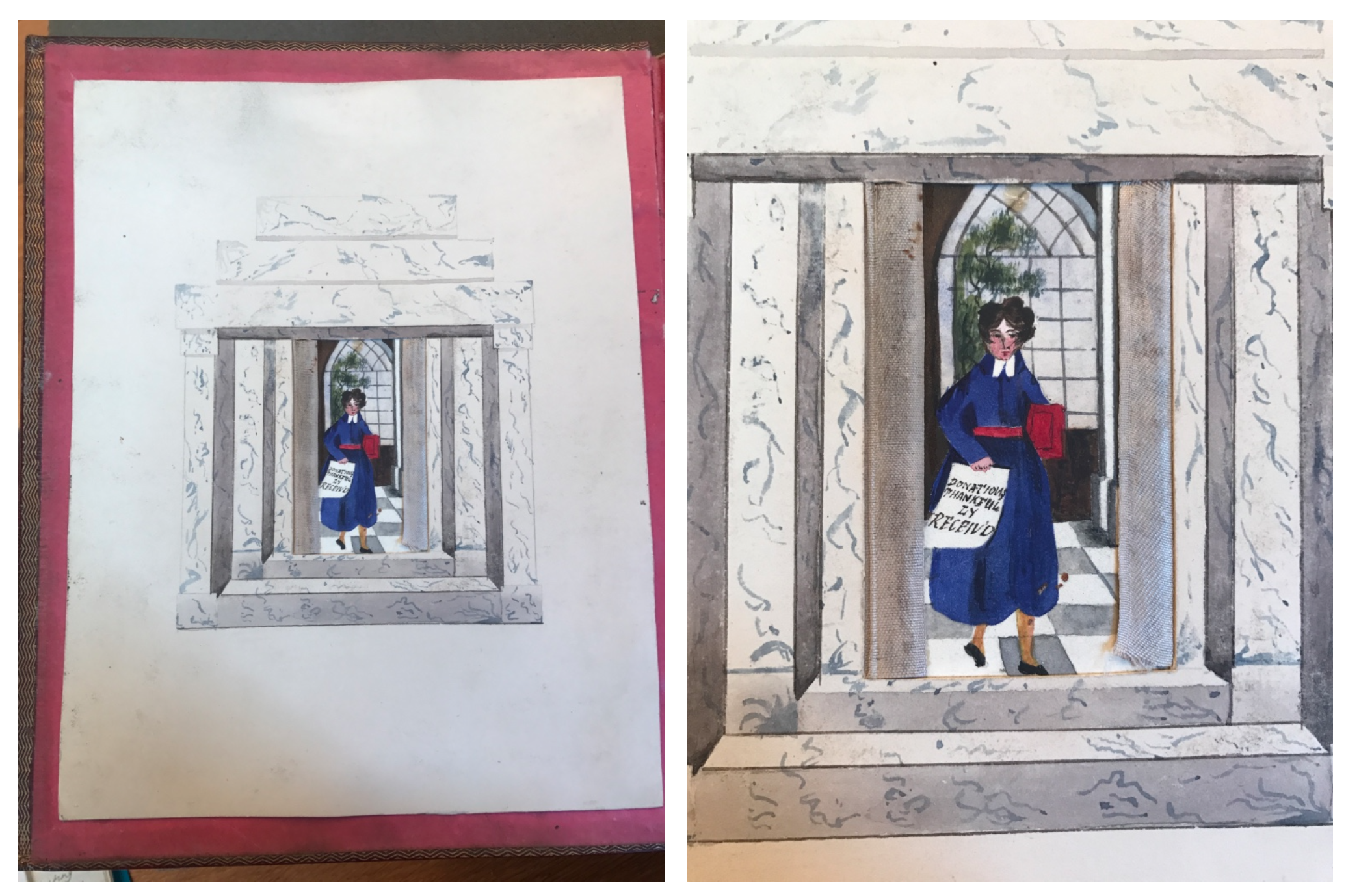

As such, the dedication functions comparably to the frontispiece of Hearne’s commonplace book, which is itself a typical example of an album frontispiece that directly addresses potential donators. The printed frontispiece to Catharine Muriel’s Commonplace Book (1824-1835), for example, features a gleeful cupid whose sack directs the reader to “Give a trifle” (Fig. 4). With his hands and bag full of album pages featuring poetic verses and watercolor flowers, these sheets pair with Cupid’s bow and arrows, notably poised for action, to form a visual nexus of the encouragement and generation of affection. Likewise, the painted frontispiece to an anonymous 1834 Commonplace Book currently in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art similarly petitions its viewers for a contribution (Figs. 5 and 6). Showing a woman standing in a marble doorway, holding her album in one hand and a sheet reading “Donations Thankfully Receiv’d” in the other, the album’s status as a collective and social enterprise is made clear. Crucially, in these frontispieces contributions are solicited using the shared visual language of album culture, a language that deploys both recognizable images of albums and album pages, as well as the very materiality of the album form, reproduced in miniature. This self-conscious mobilization and deployment of the album’s characteristics highlights the role played by such reflexive practices in both its physical and emotional construction.

LEFT: Fig. 5. Anonymous, Commonplace Book, 1834. Watercolor, 24cm. PN6245.C66 1834. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. Photograph by the author.

RIGHT: Fig. 6. Detail of Fig. 5.

In each of these images, the album functions as an autonomous and almost self-conscious object, one that can act independently if necessary, asking for donations from its owners’ friends and family even when they themselves are absent. Indeed, we know that this was a common practice, seen for example in the album of Charlotte Rose, made in Connecticut between 1825 and 1864. As one of its first entries details, the contributor was presented with Rose’s commonplace book through the hand of a mutual friend, with a request from Rose “that I insert something therein as a memorial of myself.” The text confirms that albums were inherently public documents, passed around and shared among members of social circles.[10]

Other dedications and opening inclusions also talk about albums’ peregrinations, which are sometimes likened to a pilgrimage, a term whose use interestingly conflates religious practices and sentiments with those of contemporary friendship. This is demonstrated in Emma Danforth’s 1843 album, made in Delaware, whose inner cover features an instructive couplet directly addressed to her diminutive volume, asking it to “Go forth […] and return to me.”[11] Such explicit directions also characterize the dedication to Anna Taylor’s Excelsior Album (1855-1859), written by a friend on its first pages, which implores the book to “gather up within thyself, the offerings of love, And purity, and goodness,” to “Let thy pages Call up thrilling memories,” and to “Make of thyself a storehouse, where each heart, May come and leave unfading impress, Of its love and kindred sympathy.”[12] Here, the dedication uses both specific social practices and material qualities associated with the album to ruminate upon its purpose, stressing its ability to collect and gather, while conjuring notions of the albums’ leaves as storehouses and repositories, a characterization that recalls not only di Bello’s definition of albums as belonging to “a broad category of containers of miscellaneous items, such as repositories, cabinets, and magazines, defined by what is placed within them,” but also the idea of the album as a site that sustained community and continuity among individuals.[13]

The autonomous agency of the album was also reinforced by their makers’ use of first person pronouns, as found in Charlotte Stewart’s 1838-1852 album. Here, the album opens with a jovial petition, tellingly written by “Album & Co.” (a reference, of course, to the album itself), which asks readers to “Greet my petition with a smile, as to each friend I roam; Detain me but a little while, Then send the wanderer home.”[14] Moving between owners and authors, friends and relatives, and back again, the album recalls the material protagonists of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literary genre known as the “it-narrative” or sometimes the “novel of circulation.” Once a common genre, it-narratives were a type of novel whose plot would follow the trials and tribulations of a nonhuman object, such as a lapdog or a coin, which functioned as the text’s protagonist. Like the objects that populate and narrate such texts, the early nineteenth-century album is a key inheritor of what Deidre Lynch has called the “sentimental animism” that emerges in the late eighteenth century, in which “personal effects became key to the organization of an individual’s affection.”[15] As Sara Landreth has argued, it-narratives focus not only on self-conscious objects but more explicitly on things that feel, think, sentimentalize, and ultimately empathize through narratives of material interconnectedness.[16] As such, they are a historically specific reflection on the relationship between material culture and emotion and are therefore useful for thinking about the capacity of inanimate objects like albums to provoke feelings of pleasure, comfort, and pain.[17] Beyond their shared participation in narratives of loving and leaving, both it-narratives and albums allow for a consideration of how material culture shapes the self, as evidenced by the constant slippage between subject and object.[18]

Owner and/as Album

Although their imploring frontispieces demonstrate how albums could act in lieu of their owners, the anonymous 1834 example (see Figs. 5 and 6) also highlights the parity between such volumes and their possessors. By featuring a contemporaneously dressed woman shown holding her own album, the frontispiece creates a suggestive portrait of its owner-maker, one that reinforces her implied presence in this social transaction. Visual identifications between sitter and codex were relatively common during this period, as in George Spratt’s image of a woman made entirely out of printed books, manuscript notebooks, and albums, produced in the 1830s as part of his series Twelve Original Designs.[19] Such dynamics were also explicitly addressed within contributions to albums, for example in the poem “Ladies are albums,” written by a contributor identified as “Jon” in Martha Fletcher’s album sometime after 1848.[20] Directly comparing women’s characteristics to the physical features of an album, Jon writes that “The Binding is the dress, and the unsullied page, the spotless mind. The contributions Love, Virtue, Chastity, Beware how you admit blots or stains, For all the scouring of ages will not from the fair surface remove them.”[21] Reflecting characteristically Victorian attitudes towards appropriate femininity, the poem offers a moralizing and didactic warning to keep Fletcher’s album’s pages—as well as her own character—“stainless.”

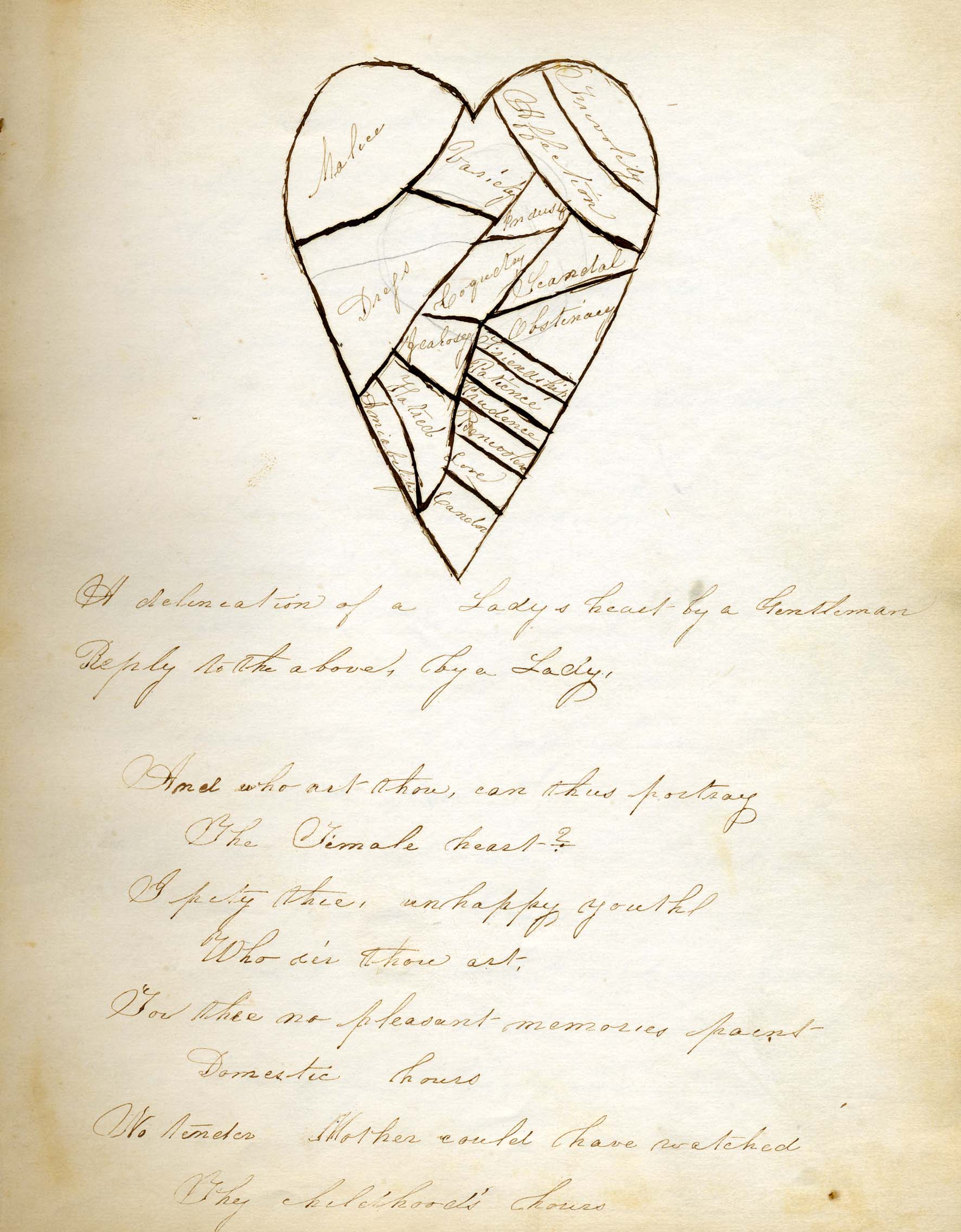

Fig. 7. Martha Fletcher, Album, 1848-1862. Pen and ink, 21cm. Doc. 1522. Winterthur Museum, Delaware. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

This revealing example of the equivalency between page and person is symptomatic of a broader trend conflating owner and object that was prevalent during the early to mid nineteenth century. Charlotte Stewart’s album likewise opens with a couplet that muses “As pure and as spotless may Charlotte’s heart be, As this leaf in her Album here scrall’d on by me,” whilst Mary Eliza Bachman’s 1831 album includes a poem that reads “May thy Album prove the Emblem of thy life, And no dark shade upon its page appears, Each page a day, each day devoid of strife.”[22] Like the frontispieces discussed above, these poetic fragments exploit typical aspects of the album’s materiality—specifically, their variously blank or filled pages—to opine on the nature of contemporary femininity, particularly the need to remain pure. When such pages are eventually written on, often by men, this act is related to an almost aggressive scrawling on the page, a poetic image that again draws upon the physicality of the practices comprising album culture to create a narrative of emotional and material possession. It is telling that in another contemporaneous album where a man illustrates a woman’s emotional life, it is with the image of a patch-worked and collaged heart (Fig. 7). Though a teasing representation—giving more space to malice, dress, and coquetry than love—the fragmented image deliberately and specifically echoes the fragmentary form of the album in which it appears. In the context of the album, the heart constitutes one of many collaged elements that together made the volume whole. At the same time, its inclusion also reinforces the connection between the album and its owner’s emotional life, echoing the assertion in Helen Mar Robertson’s Album (1837-1852) that her book was “the temple of [her] heart.”[23]

Other prefatory inclusions use this subject-object dynamic to stress the connection between contributor and album verse. As the preface to Robertson’s album declares, it was “the happy lot of [the album’s] fair owner, never to mingle with those who would contaminate the purity of its spotless character.”[24] The preface is directly followed by an indicative poetic inclusion, whose lines attest to the evocative potential of albums to recall those who wrote in them. Echoing the above assertion that an album reflected “the thoughts, feelings, and passions of those who engrave them on its pages,” the poem reads “So when, this page, thou readest alone, May mine attract thy pensive eye. And when, by thee, that name is read; Perhaps in some succeeding year, Reflect on me, as on the dead, but think my heart is buried here,” once again recalling a kind of intimate bodily connection between album and individual.[25]

Albums and Mourning Culture

Fig. 8. Helen Mar Robertson, Album, 1837-1852. Engraving with pen and ink, 20cm. Doc. 836. Winterthur Museum, Delaware. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

The album as an embodied stage for absent or dead loved ones also had an important pedigree during this period, and found consistent articulation in its visual language and characteristic inclusions. Like its preface, the frontispiece to Robertson’s album also highlights this function, this time through its printed image: an illustration of three children surrounded by flowers and urns in a graveyard who gaze longingly at a tombstone (Fig. 8). Grave-visiting had become an important site of remembrance and meditation by the early nineteenth century, because, as Pat Jalland suggests, it helped mourners “to evoke a sense of closeness to the dead person, by associating him or her with a particular place. Graves could thus become shrines which mitigated grief during a temporary period of tense anguish by keeping alive the memory of a dead person in a particularly vivid manner.”[26] Following this interpretation, the grave site can be read as functioning analogously to the album itself, with the image underscoring their shared reflective purpose.

Beneath the sentimentalizing vignette of Robertson’s frontispiece, a hand-written caption has been added that reads “Here memory comes by true affection led, To commune with the distant and the dead.” The album’s particular role in the memorialization of affection is also signaled by another inscription on the page, this time appended to the right-hand edge of the image. It reads: “Oh memory! Unfold thy magic pages, Bring to light our long lost joys!” Here, the album page is directly conflated with memory itself, where it is portrayed as acting as a crucial mnemonic device designed to prompt reflections on long enjoyed friendships and affections. Such meditations also proliferate throughout Anna Taylor’s album, compiled in and around Philadelphia in the 1850s. Opening with lines that declare “May this thy Album be to thee, when friends are scattered, early ties are broken, the strongest link in the mystic chain, that connects the present with the hallowed past,” it is filled with contributions that stress the album’s capacity to act as a “link in the mystic chain.”[27] The donator “J.A.,” for example, wrote the following in 1859: “In after years, when thou perchance […] should thine eyes, Rest on this tribute, think of me,” lines that stress how memory could be conjured while reading and re-reading album inscriptions at a later date. Finally, Taylor’s album closes with a lengthy meditation on its projected legacy within her affections:

When o’er these lines in future days,

Thine eyes shall rove in pensive thought,

Oft shall the Enchantress Memory raise,

The fairy forms of friends forgot.

The cold, the changed, the loved, the dead,

Have here alike inscribed these lines;

But since a few short years have fled,

What change is theirs, What change is thine?

Their hands have pressed thine Album’s page,

They’re left their record–passed away;

Time onward speeds–youth turns to age;

Their lines are here, but where are they?

Thy companion too, has gone her way,

Who traced these lines,–and where is she?

Yet she would at parting say,

Think, Annie, sometimes think of me.

The poem traces the contours of the complex relationship between the album and emotional performance, imagining a future where Taylor will return to the album to look over the contributions made by lost friends, family members, and loved ones. Repeatedly stressing “change,” either in the form of time passing, people aging, or even the physical changes enacted on the body by death, this mutability is contrasted with the enduring permanence of the album, which allows Taylor to reprise their collective memories. As such lines suggest, memory was particularly important during this era as a source of consolation in grief, and one intimately tied to the act of writing about such feelings.[28] Crucially, in these passages, it is the very fundamentals of the album form—pages, lines, and even individual words—that are deployed to conjure memory, as in Maggie Campbell’s 1834 album, which contains a poem that asks Campbell to “accept these lines, E’er traced in friendship’s hand, A token that love, twines, Round heart with mystic band,” wherein the lines of the poem are what ties hearts together.[29] The poem in Taylor’s Album similarly emphasizes the residual importance of the haptic act of writing in such volumes, citing hands that had “pressed thine Album’s page,” a line that underscores how reading such volumes was as much about emotional as physical affect.[30] Again, Campbell’s album offers a parallel in the form of a piece written by her cousin Frank Mariner in 1842 entitled “Remember Me.” In it, he asks Campbell to “Look through your library” to find “an ancient album,” and to “Turn over its leaves, stained by the finger of time, sit down and ponder upon the names enrolled on them, each speaks, each says, Remember Me.”[31] As Jalland has argued, such accounts were “consoling memories which sustained their sense of closeness to the deceased as well as helping them through the grieving process.”[32] Yet beyond the sentimental effusions written on their pages, the physicality of the album—as an object touched, held, and altered by the absent or the dead—also functioned across time to connect owner and contributor.

“Mine Album is a garden spot”

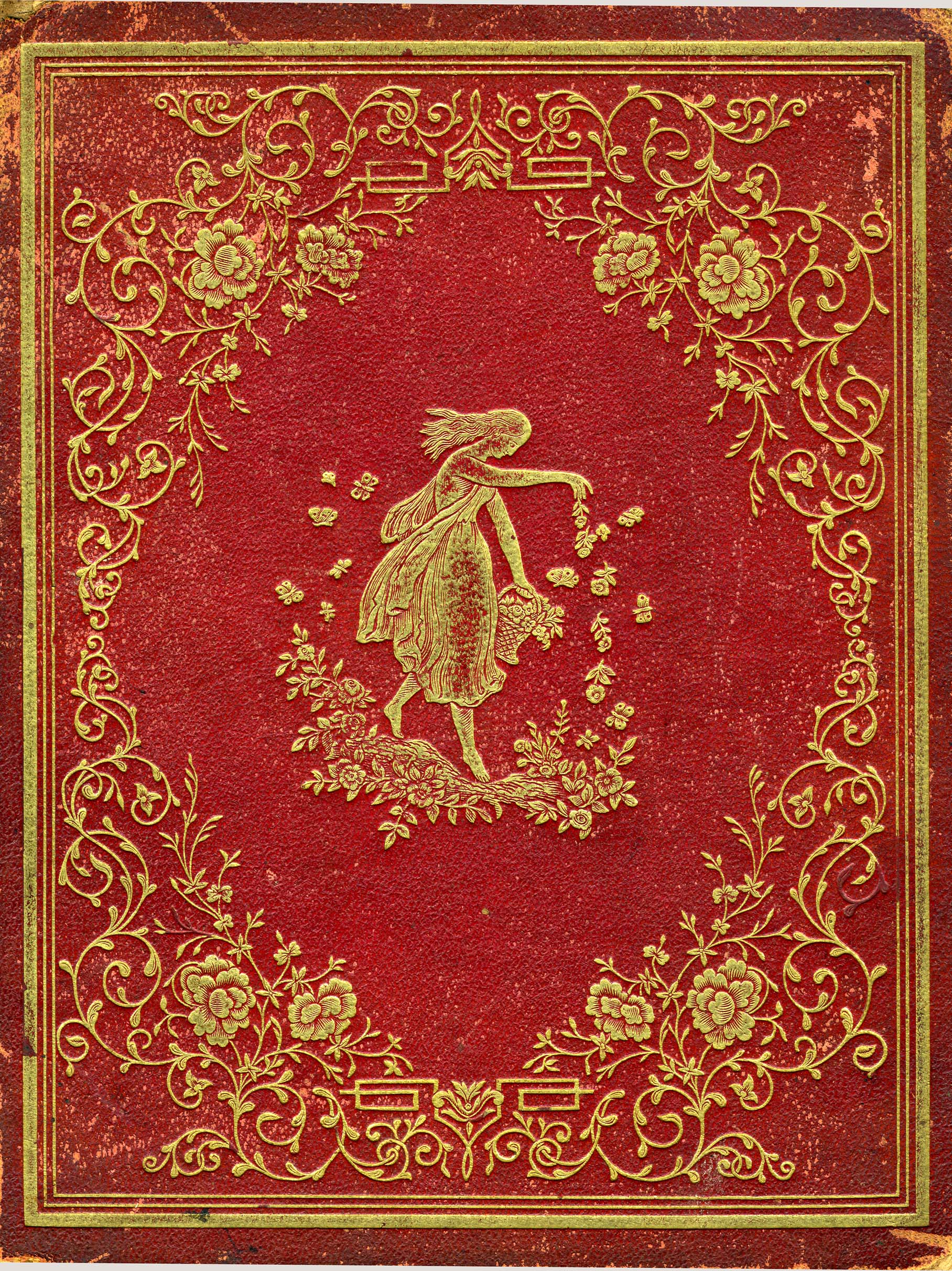

Fig. 9. Martha Fletcher, Album, 1848-1862. Leather album, 21cm. Doc. 1522. Winterthur Museum, Delaware. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

Aside from its ruminations on memory as a process materialized by album production, the frontispiece of Robertson’s album, with its graveyard strewn with flowers, also plays on the association between garden and graveyard and, by extension, between nature (specifically flowers) and emotion.[33] Outside of images of graveyards, the connection between green space and album also functioned on a more metaphorical level, in descriptions of the album as a garden. The first page of Fletcher’s Album, for example, opens with the oft-included lines “Mine Album is a garden spot, Where all my friends may sew; Where thorns and thistles, flourish not, But flowers, forever grow.”[34] Playing on the associations between an album and its inclusions, which are analogized to the whole garden versus the individual flower or plant, these lines are found in numerous albums produced between 1800 and 1860.[35] In the case of Fletcher’s album, the text corresponds directly with the volume’s front cover (Fig. 9), a maroon binding with gold tooling that depicts an image of a young, diaphanously dressed woman, who sprinkles or “sews” flowers with one hand from a basket full of cuttings in the other. Like the “garden spot” verses, versions of this cover appear on multiple contemporaneous albums, sometimes titled “Flower Tokens,” a title that reinforces the fungibility between a literal floral addition and the poetic or textual treasures donated by contributors.[36] Furthermore, both of these examples show how such sentimental verses, like the mass produced codices in which they appeared, were part of a specific and didactic language of album production that was immediately recognizable to readers and viewers.

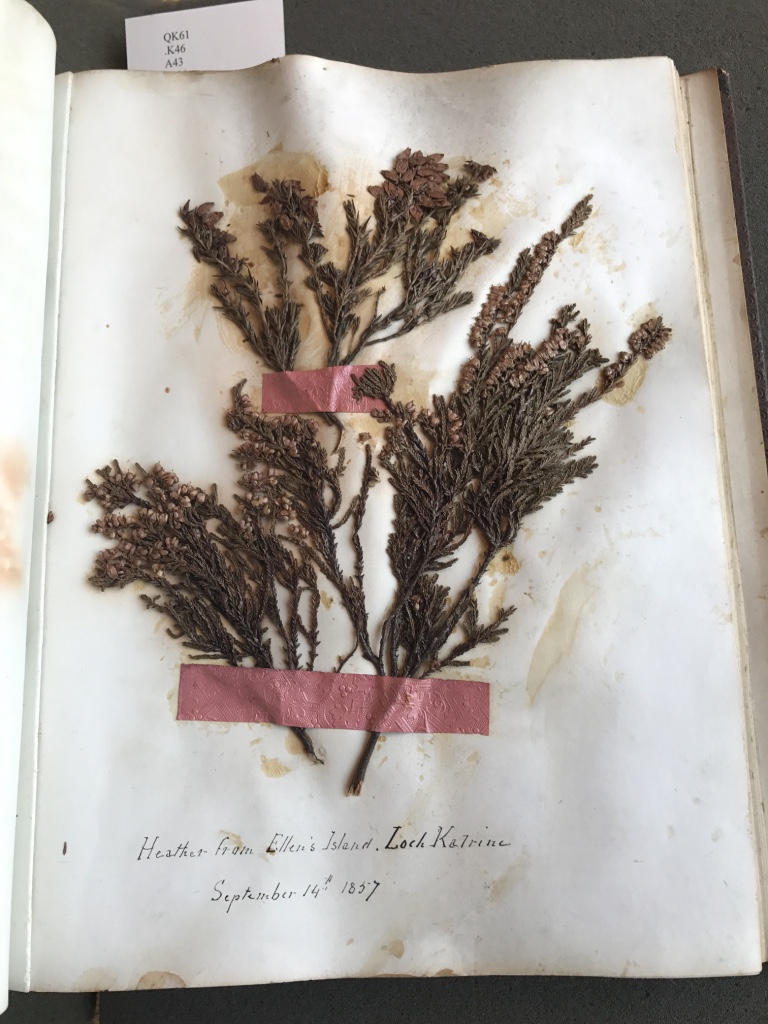

Fig. 10. Elizabeth Gray Kennedy, Album of Pressed Plants Collected during a Tour of Europe, 1857. Heather, paper, and pen and ink, 27cm. QK61.K46 A43 1856+ oversize. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. Photograph by the author.

Exploiting the genre’s varied materiality and diverse nature, albums also included an array of physical and representational floral arrangements that stressed flowers’ emotional connections and physical characteristics. An album given to Anna Gurney in Philadelphia in 1838, for example, included a beautifully drawn half-wreath of flowers encircling verses that describe the fleeting vibrancy of such blooms in real life (as countered by this replicative insertion, which would not itself fade).[37] Robertson’s own album included a similar wreath, although this was originally made from real flowers—specifically, from ragged soldiers, a wild plant native to Pennsylvania.[38] Like Gurney’s wreath, this example similarly opposes the album’s enduring survivability with its natural embellishment, and relates this contrast to the lasting, reciprocal relationship between donor and recipient. Other albums presented floral specimens that more literally connected clipping with memory. Elizabeth Gray Kennedy’s travel album of pressed plants assembled during a tour of Europe, for example, includes fronds of heather collected from “Ellen’s Island” in Loch Katrine, a spot made famous in the nineteenth century due to its association with the poetry of Sir Walter Scott (Fig. 10).[39] Functioning as a souvenir that collapsed time, space, and place, such inclusions allowed albums to conjure memories of shared experiences and affections, whilst exploiting the medium specificity of the album as a repository for a variety of sentimental inclusions, be they poetry, prose, or specimens plucked from a landscape.

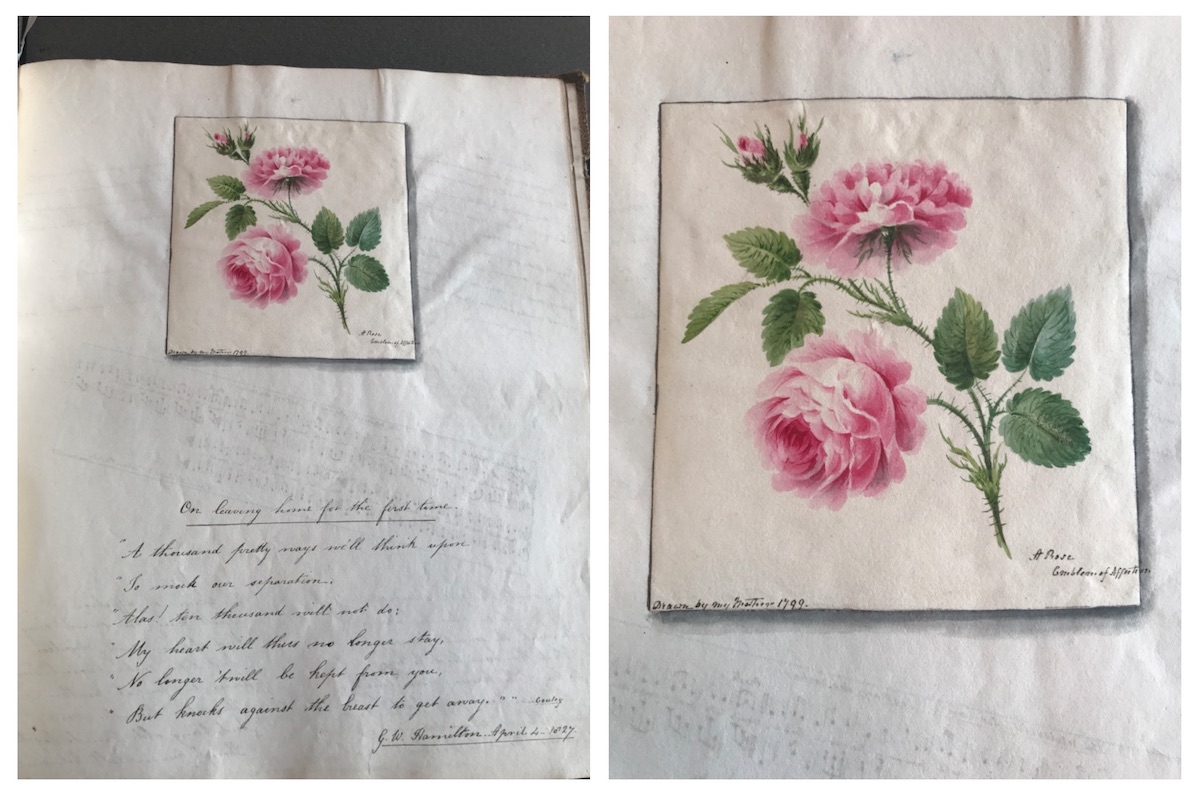

LEFT: Fig. 11. Catherine Fraser, Commonplace Book, early nineteenth century (uncatalogued at time of photography). Watercolor with pen and ink, 21cm. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. Photograph by the author.

RIGHT: Fig. 12. Detail of Fig. 11.

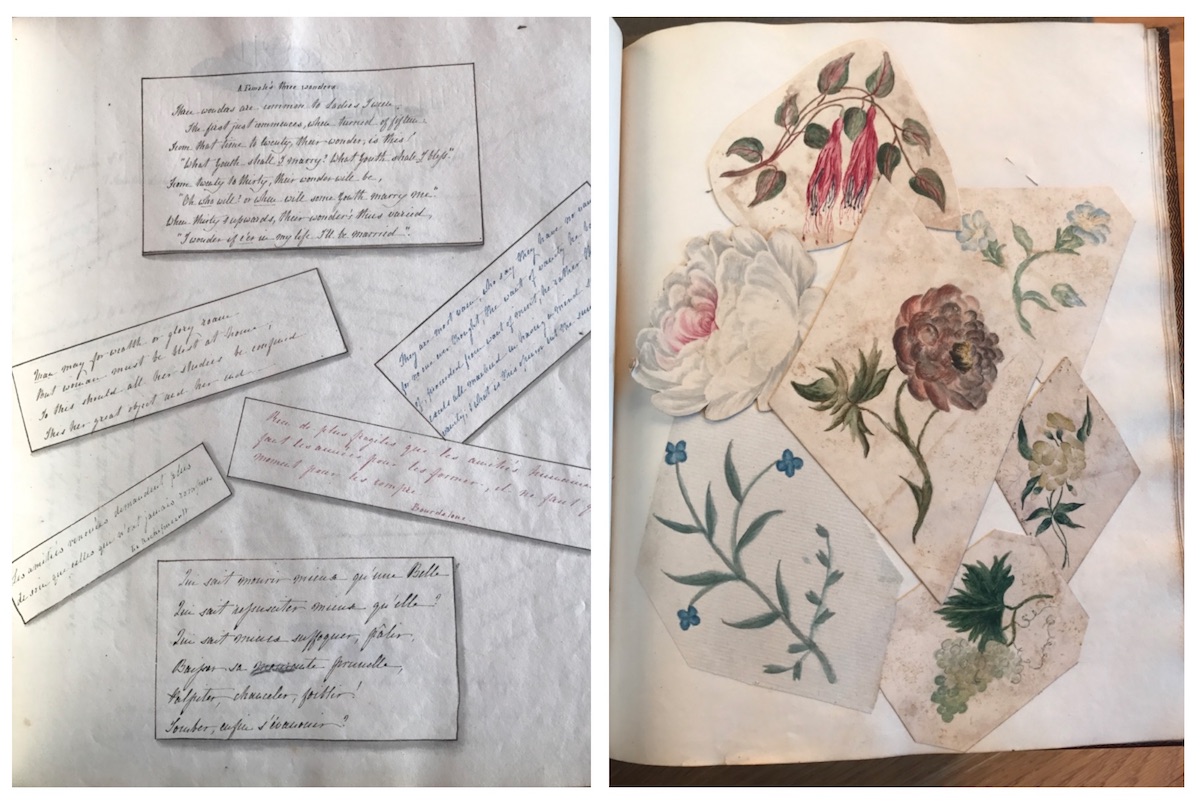

Some floral insertions played directly on the trope of album as container, as in Catherine Fraser’s early nineteenth-century commonplace book. Fraser’s album features an image of a rose painted by her mother in 1799 (Figs. 11 and 12).[40] Though a representation of a flower, as opposed to a real specimen, the illustration deploys a typical album convention: the use of trompe l’œil to suggest images and objects that were pasted or stuck onto its pages. This technique was also adopted in contemporary albums as a way to frame and delineate individual textual inclusions, or to suggest an overlapping pile of cartes de visite mounted in the album, which in reality was composed of contributors’ signatures outlined in different colors (Fig. 13).[41] Like paper assemblages of floral illustrations found in other albums (Fig. 14), collected together and subsequently glued and layered onto the page, these trompe l’oeil creations can be seen as a direct meditation on the album’s composite and collaged nature.

LEFT: Fig. 13 Catherine Fraser, Commonplace Book, early nineteenth century (uncatalogued at time of photography). Watercolor with pen and ink, 21cm. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. Photograph by the author.

RIGHT: Fig. 14. Anonymous, Commonplace Book, 1834. Watercolor, 24cm. PN6245.C66 1834. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. Photograph by the author.

More than witty visual play that merely reflected the album form, however, such illustrations also communicated the deeply affective role played by the processes of contribution that produced such volumes. The rose in Fraser’s commonplace book, for example, is labelled an “Emblem of Affection,” which, given the fact that it was drawn by Fraser’s mother, may be read as materializing powerful maternal bonds. Indeed, such emotive objects were directly tied to the birth of the album genre in dedicatory poems like that found in Mary Eliza Bachman’s 1831 album, which opens with a piece on the “Origin of Albums” that describes “a brilliant wreath” made by Friendship’s “flow’ry emblems.” Playfully stolen by Cupid, the wreath was eventually replaced by an album.[42] Again, this poem highlights the mutability between the album and the types of objects it contained, figuring both in terms of comparable emotional transaction: whereas the wreath had been made by Friendship to “speak the hopes, which language could not dare,” the album is a gift from the “Gods Above,” delivered by “the hands of Love.”

Materiality and Memory

In their meditations on long-lost friends, relatives, and lovers, albums play an active and mediating role in the dialogue between absence and presence, life and death. Like the frontispiece to Bachman’s album, which features the oft-deployed trope of the woman gazing out the window as she waits for her absent lover, the images and texts that albums include reinforce this dialogic paradigm.[43] The pages of the Fletcher album, housed in a readymade example sold by the stationer J. C. Riker in New York, for example, are punctuated by a number of typically sentimentalizing engravings. These inclusions highlight how the album was both a highly personal and particularized object, representative of the commodification of emotion that occurred from the second half of the eighteenth century.[44] Alongside representations of landscapes, the volume includes an engraving entitled “Happy Moments,” portraying a couple huddled together to enjoy an open volume. Another print depicts a young woman looking up from what looks like a letter. The image’s title, “The Valentine,” identifies it firmly as an affective document. These pictures are typical examples of the genre known as “keepsake beauties” that were part of early Victorian literary culture, appearing in annuals like The Keepsake (first launched in 1828) that were illustrated with images of beautiful young women.[45] In the Fletcher Album, such “beauties” perform a secondary and reflexive role, serving to comment on the function of the album itself as a sentimental object that conveys affection (as in The Valentine) or that might be read communally (as in Happy Moments).

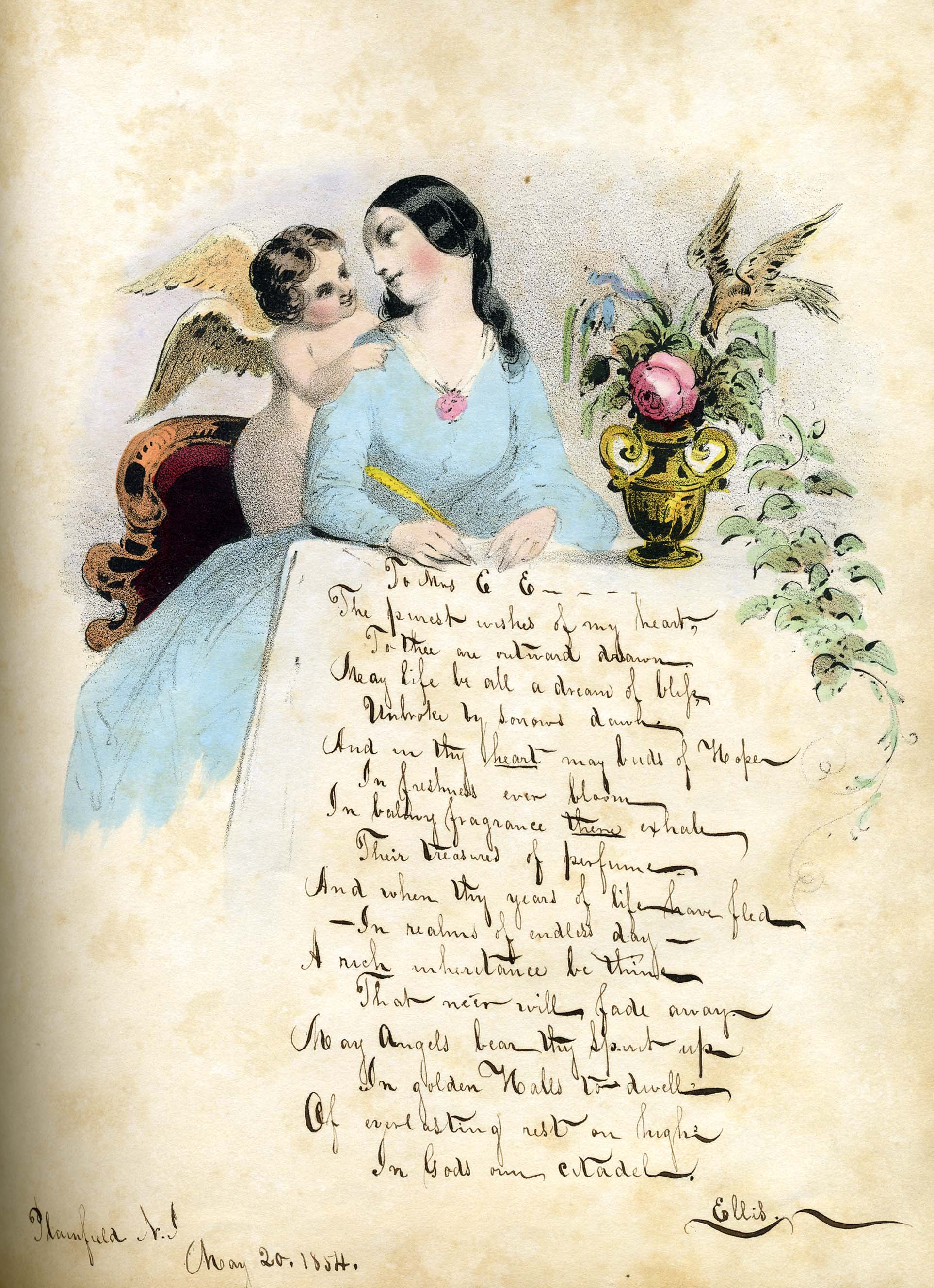

Fig. 15. Elizabeth R. Elwell, The Young Ladies Album, 1850-1883. Engraving with pen and ink, 25cm. Doc. 1409. Winterthur Museum, Delaware. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

This reflexivity is not limited to images that comment on the emotional practices of album culture. It is also characteristic of those engravings that relate to the material practices of that culture: of drawing, writing, and engaging with the physicality of the album-object. This is clearly evidenced in Elizabeth R. Elwell’s copy of The Young Ladies’ Album completed around 1850, in which saccharinely-colored keepsake beauties hold aloft the very pages that the contributor is invited to write upon.[46] In a key example, a woman bracketed by a cherubic figure on the left and a vase of flowers on the right is shown in the act of writing, quill poised above a sheet of paper that itself forms the blank space of the album’s page (Fig. 15). That such images actively influenced the responses made by an album’s recipients is made clear by the contribution’s poetic reply, which invokes a desire that “buds of Hope” may “in freshness ever bloom” in Elwell’s heart, before referencing “treasures of perfume” and asking “May Angels bear thy spirit up,” lines that correlate directly with the illustration above. This relationship between the “real” and the depicted writer is compounded via a tandem writing practice: joined at the center of the page by the paper they share, with each presumably expressing the feelings of love and affection that were typical of these volumes. Functioning as a visual shorthand for sentimentality, such engravings allowed albums to signal emotional bonds between owner, writer, and reader, a task they continue to perform for the viewer and reader today, ensuring that, even once removed from the intimacy of those relationships and the biographies of their makers, their role in the construction of affection remains clear.

Indeed, though albums are deeply biographical objects, they are often dramatically severed from those biographies through processes of archival loss and historical distancing. Though some have clear ownership and provenance, and are thereby firmly associated with owners who themselves have richly documented biographies, many are completely anonymous, or associated with a name alone. This absence of information complicates any examination of their use in the processes of self-fashioning, emotional construction, and identity formation in the period in which they were made. Despite this disruption, the reflexivity shown by these albums is a useful way of understanding their affective transactions, even after biographical ties are dissolved. Providing an active comment on the very processes and practices that they enact, this reflexivity relates directly to the specificities of the albums’ medium—the pages, frontispieces, and lines of poetry that comprise it—which in turn show how they are very much collective, social enterprises as well as documents of introspective creativity. Whether referring to an intensely personal moment and intimately tied to a specific group or pair of individuals, or functioning as a generic and typical expression of friendship or love, by the second half of the nineteenth century the album became a visual and material synecdoche for an intimate moment shared. Though they may be characterized by a recurring repository of visual referents, and couched in staid sentimentalizing language, this “standardization” was fundamental to their deeply self-referential nature, which was in turn crucial in allowing albums to construct and reflect the relationships that they facilitated and preserved.

Freya Gowrley is a Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art Postdoctoral Fellow (2018-2019) and Visiting Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh

[1] Doc. 836. Helen Mar Robertson, Album (1837-1852). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[2] On emotional objects in this period, see for example Teresa Barnett, Sacred Relics: Pieces of the Past in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

[3] For simplicity, this article will adhere to the terminology used by the collection in which the album is currently held.

[4] See Doc. 710. Frontispiece (early C19), in Lucy R. Tatnall Scrapbooks (1 of 2) (1810-1936). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[5] Christina Lupton, Knowing Books: The Consciousness of Mediation in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), ix.

[6] Lupton, Knowing Books, 1.

[7] See, among others, Patrizia di Bello, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts (Abingdon: Ashgate, 2007); and Samantha Matthews, “Importunate Applications and Old Affections: Robert Southey’s Album Verses,” Romanticism, 17:1 (2011), 77-93.

[8] Di Bello, Women’s Albums, 30.

[9] Doc. 1663. Helen S. Grover, “Album of Beauty” (1855-1867) (New York: Leavitt & Allen, c.1855). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[10] Doc. 170. Charlotte Rose, Commonplace book (1825-1864). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[11] Col. 869. Emma Danforth, Album, in Janvier, Danforth, and Bush family papers (1842-1880). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[12] Doc. 1589. Anna Taylor, Excelsior Album (New York: J. C. Riker, 1855-1859). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[13] Di Bello, Women’s Albums, 30.

[14] Doc. 954. Charlotte Stewart, Album (1838-1852). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[15] Deidre Lynch, “Personal Effects and Sentimental Fictions,” in Mark Blackwell, ed., The Secret Life of Things: Animals, Objects, and It-Narratives in Eighteenth-Century England (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2007), 64.

[16] Sara Landreth, “The Vehicle of the Soul: Motion and Emotion in Vehicular It-Narratives,” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 26:1 (Fall 2013), 94.

[17] Landreth, “The Vehicle of the Soul,” 94.

[18] For a discussion of this, see Mark Blackwell, ed., British It-Narratives, 1750-1830, vol. I (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2012), viii.

[19] George Spratt, Twelve Original Designs (Baltimore: Toy & W.R. Lucas, 1831). American Antiquarian Society, Philadelphia.

[20] Doc. 1522. Martha Fletcher, Album (1848-1862). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[21] Fletcher, Album (1848-1862).

[22] Stewart, Album (1838-1852), & Doc. 722. The friendly repository and keepsake of Mary Eliza Bachman (1831-1839). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[23] Robertson, Album (1837-1852). As Kirstie Blair argues, the heart was often explicitly gendered as female in the nineteenth century because of its “associations with intense personal emotion and feeling rather than will or reason.” Kirstie Blaire, Victorian Poetry and the Culture of the Heart (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 103.

[24] Robertson, Album (1837-1852).

[25] Robertson, Album (1837-1852).

[26] Pat Jalland, Death in the Victorian Family (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 291.

[27] Taylor, Excelsior Album (1855-1859).

[28] Jalland, Death in the Victorian Family, 286-287.

[29] Doc. 1725. Margaret S. Campbell, Album (1834-1916). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[30] Taylor, Excelsior Album (1855-1859).

[31] Campbell, Album (1834-1916).

[32] Jalland, Death in the Victorian Family, 287.

[33] As historians of Victorian mourning have documented, the addition of flowers and shrubs to gravesites was a practice that emerged during this time. Jalland, Death in the Victorian Family, 294. On the Victorian language of flowers and their emotional symbolism, see Beverly Seaton, The Language of Flowers: A History (Charlottesville & London: University Press of Virginia, 2012).

[34] Fletcher, Album (1848-1862).

[35] For example, they are also found in Stewart, Album (1838-1852).

[36] Doc. 369 “Flower Tokens” Album (c.1840-c.1849). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[37] Doc. 23. The American Offering (1838). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

[38] Robertson, Album (1837-1852).

[39] QK61.K46 A43 1856+ oversize. Elizabeth Gray Kennedy, Album of Pressed Plants Collected during a Tour of Europe (1856-57). Yale Center for British Art, New Haven.

[40] Catherine Fraser, Commonplace Book (uncatalogued at time of writing). Yale Center for British Art, New Haven.

[41] See for example, PN6245. P1861. Commonplace Book in Numerous Hands (early nineteenth century). Yale Center for British Art, New Haven.

[42] The friendly repository and keepsake of Mary Eliza Bachman, 1831-1839.

[43] The friendly repository and keepsake of Mary Eliza Bachman, 1831-1839.

[44] Fletcher, Album (1848-1862).

[45] Kathryn Ledbetter, “‘White Vellum and Gilt Edges’: Imaging The Keepsake,” Studies in the Literary Imagination 30:1 (Spring 1997), 35-47.

[46] Doc. 1409. Elizabeth R. Elwell, “The Young Ladies Album” (1850-1883). Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

Cite this article as: Freya Gowrley, “Reflective and Reflexive Forms: Intimacy and Medium Specificity in British and American Sentimental Albums, 1800-1860,” Issue 6 Albums (Fall 2018), https://www.journal18.org/3036. DOI: 10.30610/6.2018.4

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.