Grand Salon from the Hôtel de Tessé, Paris (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Image courtesy of www.metmuseum.org.

Can a period room be brought back to life? In the spring of 2015, twelve Barnard and Columbia undergraduates and I made the attempt, in a seminar called “A Virtual Enlightenment.” We had the support of the Mellon Foundation, the collaboration of Metropolitan Museum of Art curators Jeffrey Munger and Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide, and the skills of Alex Gil from the Columbia Digital Humanities Center. Our goal was to make one of the Met’s Wrightsman Galleries period rooms, the Tessé Room, digitally usable.

By “digitally usable” I meant two things. The first was to make visible or legible the uses to which the room and its contents had been put. The second was to train undergraduates to use digital technologies. Those two aspects of the project proved to be intertwined. At “usable” the eighteenth century met the twenty-first.

As I prepared and taught “A Virtual Enlightenment,” I became convinced that digital technology, at the very least, enables us to see uses of the decorative arts invisible since the eighteenth century. I now would argue that digital technology inspires attention to use, and summons questions that before would have been inconceivable. We may be at one of those moments in the history of the history of art at which some essential moves forward are not only about content, but also about form.

This may be truer of three-dimensional than of two-dimensional art, and truest of the usable three-dimensional arts. And where better to start than with the material culture of eighteenth-century France, which swerved the daily life of ordinary people in such a decisively modern direction? Our century’s digital knowledge can build a bridge back to a lived Enlightenment knowledge. Meanings that were forgotten can now be perceived. A new era of decorative arts scholarship could be emerging.

Needless to say, a collection like the Met’s might not, at first, seem appropriate to such a project. The Met’s decorative arts collection was assembled according to aesthetic or technical criteria, and sometimes according to provenance. What might seem to distinguish the Met’s period rooms and their contents is their luxury and opulence, along with the exceptional rank of those who commissioned and owned them. Decorative arts scholarship prior to about the 1990s was largely devoted to the aesthetic quality judgments and factual research that assembled such collections.[1] For generations, finely grained knowledge accumulated about style, authorship, and techniques. Without this knowledge, we would have no foundation on which to build new sorts of inquiries.

One student team did work on an exceptionally beautiful furniture pair by Jean-Henri Riesener, a secrétaire and a commode, with a magnificent provenance. They first belonged to Queen Marie-Antoinette. Rather than stop the furniture’s story there, however, students used authorship, technical prowess and pedigree to launch projects about issues that innovative scholarship has recently introduced us to: projects on the global trade that brought to France the furniture’s Japanese lacquer panels; on the personal child-parent relationship between Marie-Antoinette and Empress Maria-Theresa, whose gift of a lacquer collection inspired her daughter’s commission from Riesener; and on the commodity culture that promoted luxury goods.

These sorts of student projects showed how points or arguments that scholars have been making over the past two decades can be reinforced when they are combined with their digital visualization. One student, for instance, used Photoshop to pull apart the Riesener secrétaire’s Japanese lacquer from its quintessentially French gilt-bronze mounts, in order to compare and contrast their color schemes and styles. Another project used Photoshop to put Maria Theresa’s lacquer collection gift right back into the rooms at Versailles where Marie-Antoinette first displayed them.

Alongside studies of a global eighteenth century, and studies of individual identities constructed with things, historians of eighteenth-century “decorative arts” have drawn increasing attention to the meanings of use. Attracted by the simple fact that many (though not exactly all) the decorative arts were designed to be used, historians have initiated what I would call a phenomenology of use. Desks, in particular, have been compellingly re-thought. Desks’ kinetic complexity, delicacy, lockable drawers and keyholes have all been revealed. Desks, it turns out, were privacy machines. Here too, “Virtual Enlightenment” students realized how use could be digitally recreated. One did an animation of Riesener’s secrétaire, so that its many drawers and compartments gradually open before our eyes. Then, virtually, the student put some of the Queen’s most personal possessions into the opened drawers.

Spurred by each other’s digital experiments, students discussed the meanings of use. We are accustomed to the textual enunciation of ideas. Of course, words express ideas, for instance a declaration of equal rights in words. But things, too, express ideas, to some extent in their transformation of raw material or treatment of form, and more as they are used. Some meanings, especially in the decorative arts, could be considered latent in form, or inert, until use.

Use enunciates ideas. Equal rights, to return to the previous example, are declared when everyone in a group sits on a matching chair or sofa. Individual self-actualization is felt while reading and writing on comfortable upholstered chairs with ergonomically designed arms and legs. The written declaration of equal rights has the advantage of concentrated eloquence. The seats have the advantage of long and repeated use. Things create habits of body and habits of mind.

Four seminar sessions at the Met, where Munger and Kisluk-Grosheide generously allowed students to look closely and hold real objects, incited students to believe that use by owners can be encoded in materials and form. High-resolution details allowed them to present objects as if they were in use, to reconstruct an experience of them, with a visual intimacy lost behind vitrine glass or period room cordons. This could be called a part of the material turn in art history. But it was striking to me that undergraduates needed no historiographic prompting to take that turn, only the combination of physical experience and huge digital files.

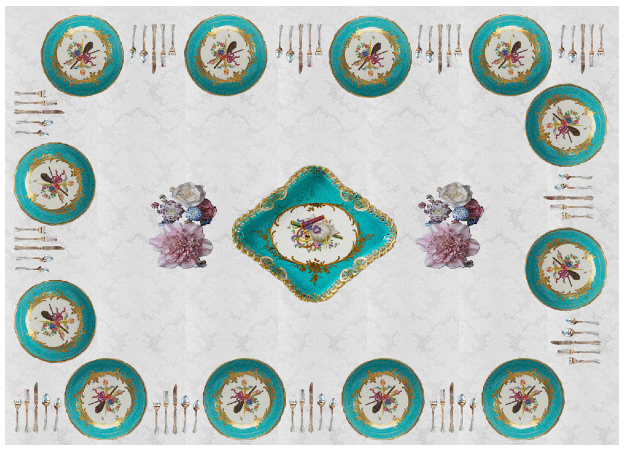

After, for example, Munger had shown students how snuff boxes were twirled in the hand, and how, therefore, all six sides of snuffboxes were decorated – whereas snuffbox backs and bottoms can rarely be seen in a vitrine – one student realized that the handling of a snuffbox looked very much like the conventions of movement in 3-D Rhino modeling. As a result, now one of the Met’s most important snuffboxes rotates in space online, at your command. Another student was fascinated by how bright the colors invented by the Sèvres porcelain manufacture looked in person at close range. She designed solid color blocks to bring out the hues, and recreated the visual effect of an eating surface covered with plates.

These and countless other possible digital devices enhance visibility to such a degree that the borderline between the visual and the tactile becomes very fine. The digital sight of something can be so intimate, so close or so mobile, that it convincingly evokes the sense of touch. Once touch is evoked, it becomes inevitable to summon the bodies that did the touching.

From the start of the seminar, students wanted to repopulate the Tessé Room. To begin with, they felt that many aspects of the room’s use were hard to imagine without the scale and clothing of human beings. Did a desk designed for women not look much more feminine when its legs vanished amid the billowing skirts of a woman pulled up to it in a chair? If the angle of a chair-back was exactly the same as the angle of a set of stays, would women not be rather more at ease in a chair than we might assume? Several projects digitally reinserted members of the owning class into the room.

More important to the seminar students, however, was the reinsertion of people who might have seemed invisible in a room like the Tessé Room even in the eighteenth century. Servants are the feature most sorely missing from every period room. The more lavish the room (the more, that is, like a Met period room) the more servants it required. Teams of servants spent entire adult working lives managing, cleaning, repairing, or guarding the decorative arts. Their experience was a kind of use as vital as use by owners, and as productive of meanings.

One of the easiest accusations to make against a period room like the Met’s Tessé room is its ostentatious expense, which could seem to make it relevant only to a tiny aristocratic or royal elite. Yet the opposite is true, and we can make that truth visible. We can visualize the work that put servants in constant physical contact with the decorative arts. That work, furthermore, can be productively understood through a new attention to materials and form. The instant students looked closely at a great silver coffeepot by François-Thomas Germain, for example, they began to contemplate how long it would take to polish all its details. Whatever expansion of an owner’s world horizons was suggested by drinking coffee imported from Africa, Sumatra, Java, Brazil, or Martinique out of silver imported from South America, some version of the same must have occurred to the servants who served the coffee and polished the silver.

Close attention to materials and form also brings artisans back into the period room. Once the extraordinary degree of finish and intricacy of any of the eighteenth-century decorative arts becomes inescapably visually evident through close up or animated digital imagery, it immediately confronts us with the skill involved in their making. Both the quality and the quantity of labor become visible. Or rather, they become publicly visible. The evidence was always there, in the object itself. Yet inside a vitrine, behind a period room cordon, it can hardly be seen, especially when light levels are low for conservation reasons. A favorite seminar example was lace. Until high resolution images makes visible every knot and stitch, it is impossible to understand the labor that produced lace. The minuscule part demands a calculation of the whole. If every stitch had to be made by hand, how many hours did it take to make a single engageante sleeve ruffle, or for all the lace represented in one portrait to be made? From the oblivion of history, work resurfaces.

As student website projects got underway, plates from books about the arts et métiers, especially the Encyclopédie, became an increasingly appreciated resource. The more students saw in objects, the more they valued the tools and hands that had made what they saw. The evidence of the visible led from tools to hands back to raw materials, just as Denis Diderot intended. And in the spirit of Diderot, a website can easily re-join any object in a period room with the type of artisan who made it and with the conditions of its making, through an arts et métiers plate. Channeling Diderot, a finished object and its maker can also be reunited with raw material, through a photograph much more realistically colored and textured than a black and white engraving.

In the end, “A Virtual Enlightenment” pushed furthest away from existing decorative arts scholarship when it tried to do for artisans what scholarship has done for the owning class. If the post-creation use of decorative arts by owners performed meanings, I would argue that the creation process did so too. The ideological usability of objects, “A Virtual Enlightenment” proposes, begins the moment a design process originates and extends throughout the entire execution of objects. A seamstress updating the style of a sleeve was absorbing consumer culture. A locksmith making a keyhole was learning about privacy or freedom of thought.

And again, as in the case of servants’ relationships to decorative arts, the luxurious excellence of the sort of decorative arts in the Met’s collection only magnified their ideological impact on artisans. The longer it took to make something, or the longer it had taken to acquire the skills to make it, the more evidently valuable must its ideas have been to the one who did the making. Perhaps, for instance, the new buying power of women was not articulated as an abstract concept or a written text in Martin Carlin’s workshop, where porcelain plaques painted with flowers were integrated into delicate tables dedicated to feminine occupations. It was certainly, however, an idea learned during countless hours of labor.

Ultimately, I would hazard this proposition: that workers in the arts et métiers experienced the Enlightenment first and foremost in the making of things, at its most refined level, in the making of decorative art objects. First, because chronologically, the decorative arts of the Enlightenment came before its great textual enunciations. Foremost, because it was learned as skill, as knowledge inculcated by years of apprenticeship and gradual mastery.[2] Skill is knowledge that works on both sides of the divide between mind and hand. “A Virtual Enlightenment” dedicated itself to those historically specific meanings skill invented during the extraordinary burst of creative invention between about 1680 and 1720, perfected in the following decades, and culminated – arguably — in the French Revolution.

Like skill, the word “usable” swings alternately toward practical use and toward knowledge. This from your nearest online dictionary: “us·a·ble/adjective: useable/able or fit to be used, as in: ‘usable information’.” The meanings expressed in the decorative arts could be considered usable information.

If the word “usable” sounds familiar, it is because it has been become a mantra of digital information technology. It is tightly associated with the new digital concept of “universal usability.” Universal usability, according to Wikipedia – the namesake of Diderot’s Encyclopédie, which also, in its time, aspired to universal usability – applies equally to designers, developers, and users. A useable period room, I would say, is one whose original meanings, experienced by its designers, makers, and users, are made universally accessible by today’s digital designers and developers to museum and internet users.

The usable period room website is a work in progress. Two current senior essays continue to add to it. The seminar will be held again in the fall of 2016, which will expand the website in unforeseen directions. Other period rooms could be added, from the Met, or potentially from other museums. Other topics or approaches could be tried. Other schools could join the project. All suggestions are welcome.

Anne Higonnet is Professor of Art History, Barnard College, Columbia University, NY

[1] Especially helpful to students were: Dena Goodman, Becoming a Woman in the Age of Letters (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), Part III: “The World of Goods”; Mimi Hellman, “Furniture, Sociability, and the Work of Leisure in Eighteenth-Century France,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, 32:4 (Summer 1999), 415-445; Daniel Roche, La culture des apparences. Une histoire du vêtement (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles) (Paris: Fayard, 1990), “Introduction: Culture and Material Civilization,” “Clothing and Appearances,” and “From Scarcity to Luxury”; Carolyn Sargentson, “Looking at Furniture Inside Out: Strategies of Secrecy and Security in Eighteenth-Century French Furniture,” in Dena Goodman and Kathryn Norberg, eds, Furnishing the Eighteenth Century: What Furniture Can Tell Us about the European and American Past (New York: Routledge, 2007); Katie Scott, “Framing Ambition,” Art History, 28:2, (April 2005), 248–290; William Sewell, “The Rise of Capitalism and the Empire of Fashion in Eighteenth-Century France,” Past and Present, 206:1 (2010), 81-120; Kristel Smentek, Rococo Exotic: French Mounted Porcelain and the Allure of the East (New York: Frick Collection, 2007); and Michael Elia Yonan, “Veneers of Authority: Chinese Lacquers in Maria Theresa’s Vienna,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 37:4 (Summer 2004), 652-672.

[2] This is of course not new to the eighteenth century, indeed it calls to mind Pamela Smith’s Making and Knowing Project, concerned with the sixteenth century.

Cite this note as: Anne Higonnet, “A Digitally Usable Period Room”, Journal18 (2015), https://www.journal18.org/224

Licence: CC BY-NC