Christine Casey, Making Magnificence: Architects, Stuccatori and the Eighteenth-Century Interior, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017.

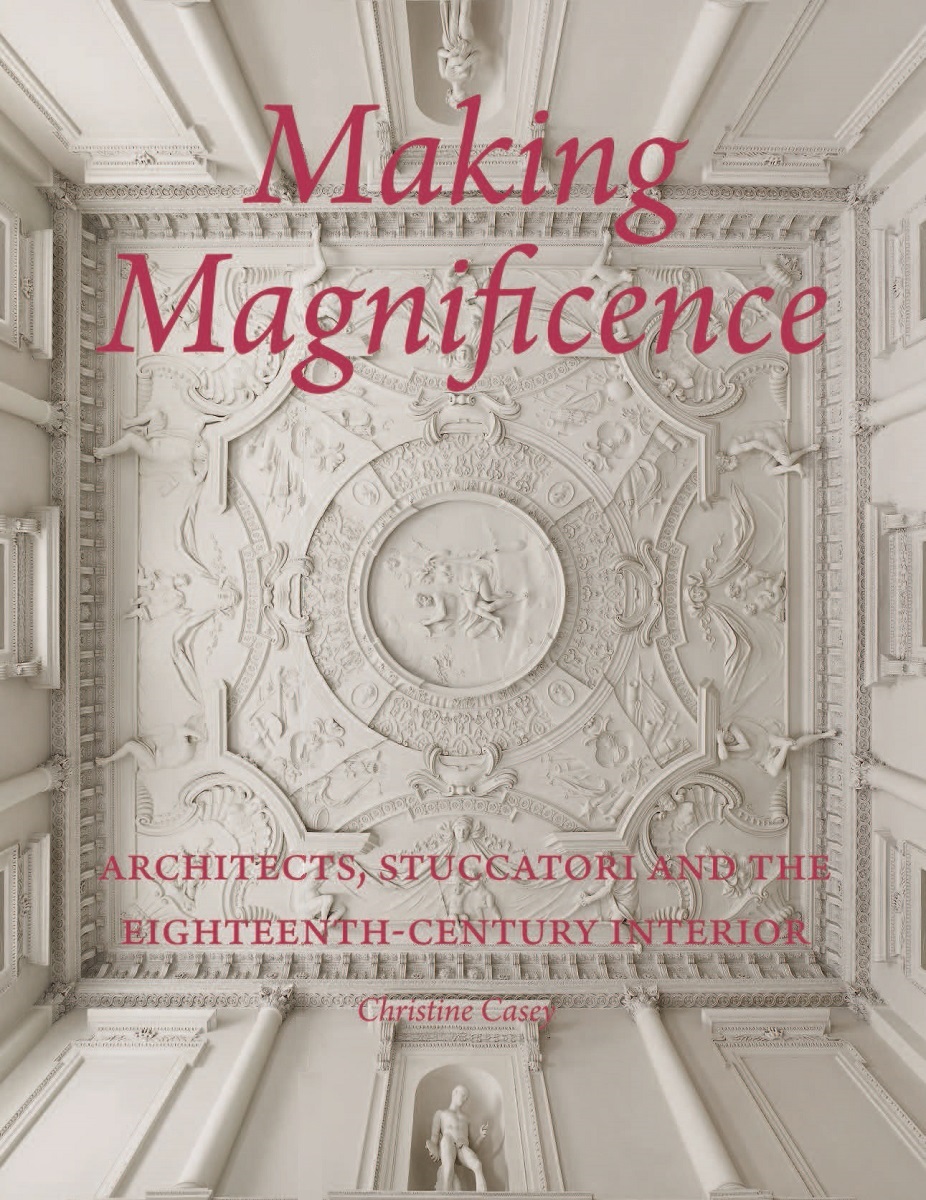

Combine lime and gypsum with water, then add stone dust or sand and animal hair to strengthen it: this modest, somewhat dubious-sounding recipe produces stucco. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, stucco was used to create massive illusionistic interior architecture, to frame paintings with anything from gambolling cherubs to modest garlands of foliage, or to offer its own pictures, be they of saints and angels springing off the walls or of gods and goddesses set against the most delicate reliefs of clouds. Christine Casey’s Making Magnificence explores the lives of the stuccatori, the master craftsmen who worked with a material that she characterizes as a “chameleon,” emphasizing stucco’s remarkable versatility and its ability to simulate a wide range of other substances (p. 9). While studying the craftsmen does lead Casey to comment on specific stucco projects extensively, she doesn’t engage with stucco in the way that art historians interested in materiality have engaged with other materials elsewhere. Ultimately, her work is instead a rich contribution to the social history of architecture, and it invites reflection on the relationship between architectural materials and designs.

Although the book keeps recent theories of materiality at arm’s length, it is firmly grounded in studies of plasterwork. It represents a relatively unusual approach: in comparison to studies of materiality in art works and objects, studies of materiality in architecture are rare. Casey’s exploration of what could be achieved with stucco encourages readers to consider this, and it also offers a compelling argument for greater attention to the relationship between ornament and architecture. Casey cites writings by James Trilling and David Brett as inspiring her own methodological approach to the role of decoration in interiors.[1] In re-examining the relationship between ornament and architecture in early modern interiors, her work complements recent projects that have demanded reappraisals of the so-called decorative in other media, such as studies on decorative history paintings in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Britain and the exhibition Taking Shape: Finding Sculpture in the Decorative Arts (2008-2009) curated by Martina Droth for the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Henry Moore Institute.[2] Casey explores ornament and design, hierarchy and craft through an intense focus on the stuccatori (especially those active in Britain and Ireland), the European tradition they came from, and the way their works ranged from the sensual and gestural to the formal and orderly.

In the first three chapters, Casey builds up a rich picture of the lives of the stuccatori, of their home communities and journeys through Europe. Most of these men came from one of the villages surrounding Lake Lugano, now part of Canton Ticino, a long narrow region of Switzerland stretching into Italy. The foothills of the Alps supported several trades and crafts related to stone; the art of the stuccatore, who transformed stones into highly versatile plaster, was a prestigious and potentially lucrative trade, albeit one that required prolonged absences from home. Connections between families and workshops were extensive, creating extraordinarily powerful and productive networks. Throughout the book, there is a subtle tension between the role of the individual and the strength of the collective: while Casey successfully outlines the careers of a number of master stuccatori, identifying their major projects and the attributes of their different styles, she also implies that to invest too much energy in this direction would be to miss the point entirely—success with stucco depended on cooperation more than individual genius. She identifies agency, organization and consumption as critical criteria for analysis (p. 38), and she entwines her insights into the lives of individual stuccatori with broader questions about their practices. While examining the professional training and workshop practices of the stuccatori, for instance, she discusses the significance of disegno for designing stucco, exploring the role drawings played in dealings with clients and architects. It is the latter relationships which are among the most fascinating elements of the book: in spaces where it is practically impossible to tell where architecture ends and stucco ornament begins, the extent to which architects and stuccatori relied on each other and their abilities to collaborate successfully were fundamental to effective design.

In the second part of the book, Casey turns her attention to close discussion of stucco projects. Stuccatori worked in a wide range of religious and secular buildings: major works examined here include the palace of Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden-Baden at Rastatt (Fig. 1), the Abbey Church at Fulda, the Hôtel de Ville at Liège, the Palatine Chapel at Aachen, Saint Martin-in-the-Fields (Fig. 2), Houghton Hall, Wentworth Castle and Carton House. Taken together, these buildings illustrate how the craft of the stuccatori was adapted for German, Austrian, British and Irish interiors such that the tastes of different nationalities were satisfied while the stuccatori continued to build on the successes and strengths of their practices. These were craftsmen who were deeply conscious of cultural and national divisions—for instance, many struggled with the challenges of worshipping according to the Roman Catholic faith while working in Protestant countries—and yet they regularly moved across them, reinventing magnificence for a wide range of patrons. The stuccatori could deploy their “chameleon” material in a wide variety of ways, and for a comparatively low price.

In introducing her project, Casey speculates that it has “a hint of the manifesto” in it (p. 6). There can be no doubt that some of this book’s most powerful lessons are not really about the stuccatori at all. Rather, by rigorously and comprehensively investigating the use of stucco it challenges us to look critically at interiors, to make ornament integral to analyses of space and to reflect on our own preconceptions about the decorative. In their own time, the stuccatori were often relegated to a lower status than architects and artists, and modernist attacks on ornament have reverberated for decades, diminishing them even further.[3] Above all else, Making Magnificence demonstrates that the stuccatori deserve to be recognized for the crucial role they played in creating spectacular interiors in eighteenth-century Europe.

Jocelyn Anderson is an art historian specializing in eighteenth-century British art and architecture. She is based in Toronto.

[1] James Trilling, The Language of Ornament (London: Thames & Hudson, 2001); James Trilling, Ornament: A Modern Perspective (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003); David Brett, Rethinking Decoration: Pleasure and Ideology in the Visual Arts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

[2] See, for instance, Richard Johns’s “‘Those Wilder Sorts of Painting’: The Painted Interior in the Age of Antonio Verrio,” in A Companion to British Art: 1600 to the Present, ed. Dana Arnold and David Peters Corbett (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 79–104; and “Antonio Verrio and the Triumph of Painting at the Restoration Court,” in Court, Country, City: British Art and Architecture, 1660 – 1735, ed. Mark Hallett, Nigel Llewellyn, and Martin Myrone (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016), 153–76. See also Lydia Hamlett, “Rupture through Realism: Sarah Churchill and Louis Laguerre’s Murals at Marlborough House,” in Court, Country, City, 195–216; and Taking Shape: Finding Sculpture in the Decorative Arts, ed. Martina Droth and Penelope Curtis (Leeds: Henry Moore Institute, and Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2009).

[3] James Trilling, Ornament: A Modern Perspective (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 4.

Cite this note as: Jocelyn Anderson, “Making Magnificence: A Review,” Journal18 (August 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1895

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.