Paris Amanda Spies-Gans

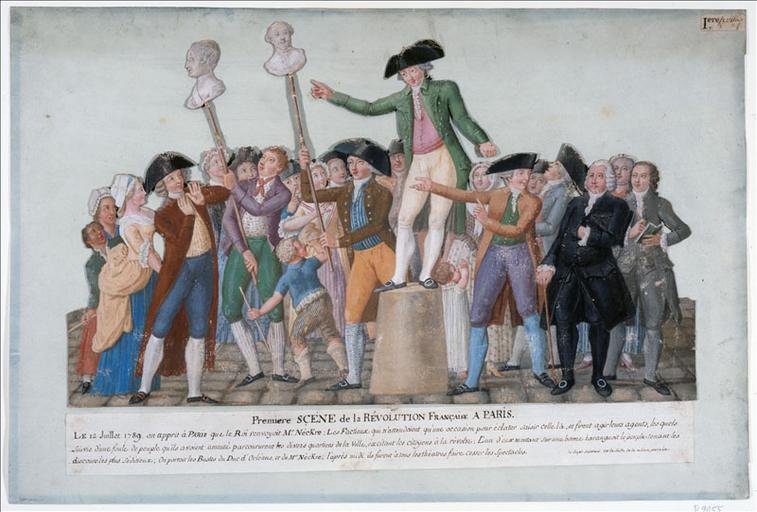

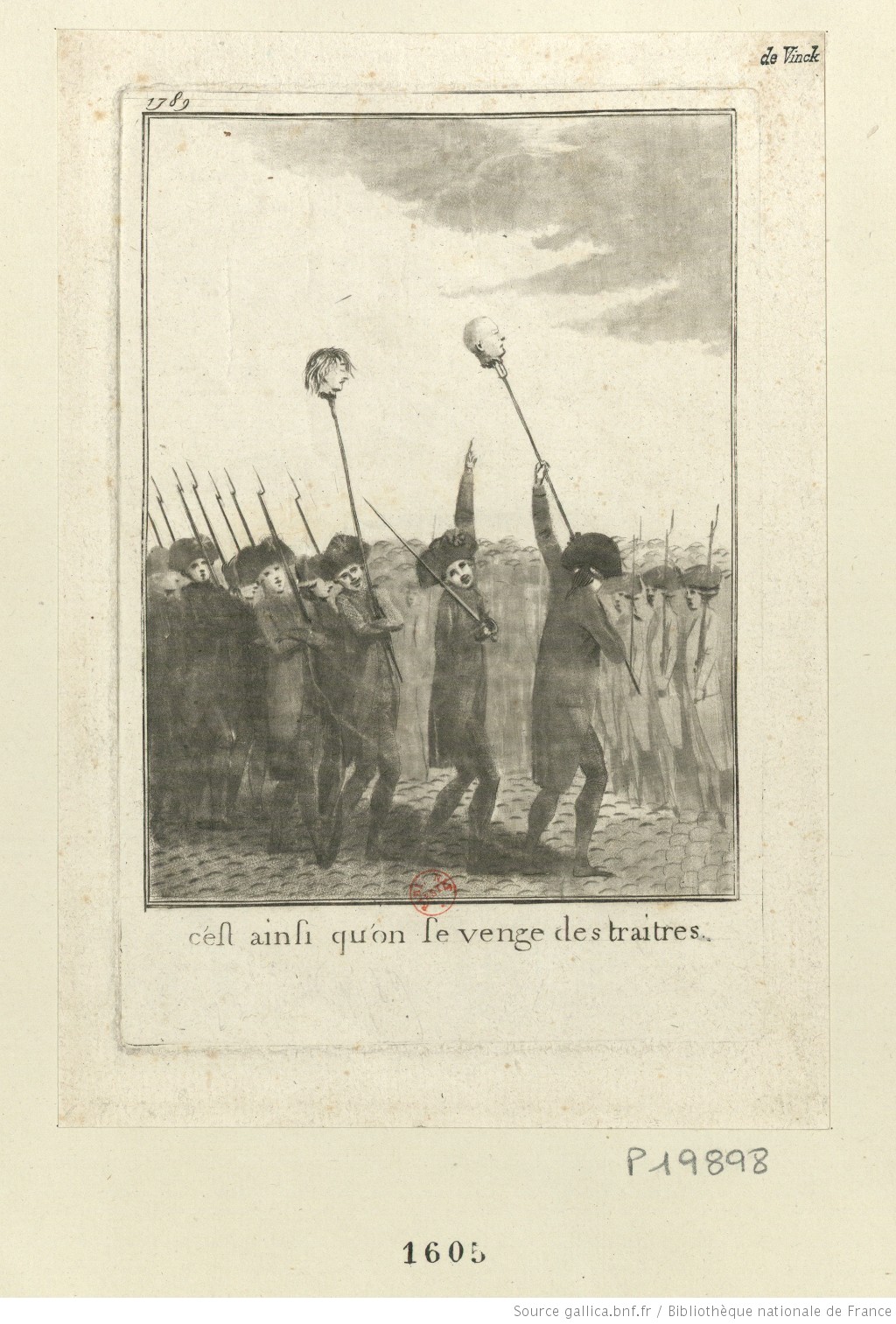

On July 12, 1789, Parisians began to revolt. News had just arrived that France’s King Louis XVI had dismissed his trusted finance minister, Jacques Necker. Accordingly, in a contemporary print by Jean Baptiste Le Sueur, The Beginning of the French Revolution, the orator Camille Desmoulins advocates a search for arms, anticipating imminent governmental repression and the need for defense (Fig. 1). Yet Le Sueur does not depict weapons. Rather, he directs viewers to two mounted portrait busts—the elevated wax heads of Necker and the duc d’Orléans, the popular, anti-royalist cousin of the king. Earlier that day, the crowd had borrowed these two figures from Philippe Curtius’ popular Salon de Cire on the boulevard du Temple, and then paraded them, shrouded in funereal black crêpe, to the Place Vendôme. The Royal Guard allegedly refused to salute the wax portraits and, instead, opened fire, initiating the first bloodshed of the Revolution.[1] The battle-scarred busts were returned a few days later to Curtius’ Wax Salon, which had, in the interim, received two additional heads on pikes: the real heads of crown servants who had defended the Bastille on July 14. They, too, had been paraded triumphantly through Paris, as depicted in an anonymous etching from 1789 (Fig. 2). Curtius had joined in the storming of the Bastille, and was not at the Salon to receive these heads. Instead they were taken in, and immediately immortalized in wax, by his twenty-eight-year-old protégée, Marie Grosholtz, later Tussaud. Taken quite literally to embody Revolutionary heroes and victims, wax portraits played a pivotal representational role in the momentous summer of 1789.

Fig. 1. Jean Baptiste Le Sueur, Première scène de la Révolution française à Paris, 12 juillet 1789, c. 1792-95. Gouache on cardboard, cut and glued onto a sheet of watercolor paper, 26 x 53.5 cm. Musée Carnavalet, Paris. Image in the public domain.

Fig. 2. Anonymous, C’est ainsi qu’on se venge des traitres, 1789. Etching and aquatint, 18 x 12 cm. Image source: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France.

While the story of these paraded wax busts remains famous in Revolutionary history, Tussaud’s artistry rarely features in studies of the era.[2] Instead, she is often dismissed as a craft worker, or simply non-Academic, due to her choice of material and dominant mode of exhibition: a ticketed, traveling show. Yet Tussaud’s wax figures were central to the Revolutionary world, both as portraits and as lifelike representations of their subjects. While it is difficult to analyze Tussaud’s oeuvre, as only her original molds survive, contemporary prints, correspondence, advertisements, and reviews testify to the lasting impact of her work. Even while operating outside of Academic institutions, Tussaud was an active participant in the art historical currents of her time, engaging with trends and influencing others. Ideas of lifelike portraiture were essential to her work, and her career had widespread implications for the self-fashioning of female artists and for a public that vocally admired her artistry for over half a century. This short essay advocates for a more serious study of Tussaud’s career through the lens of art history, and for her placement in the historiography of the Revolutionary era more broadly.

Marie Tussaud (1761-1850) grew up in the household of the anatomical wax modeler Philippe Curtius (d. 1794), who trained her from a young age.[3] She would always refer to him as her “uncle” and, at his death, Curtius left her his entire collection, calling her “my pupil in my art.”[4] This domestic context is important—Tussaud learned her craft from a father figure, in an apprentice-like relationship, much as other women artists learned to paint in male artists’ Louvre studios in these years. The genre painter Marguerite Gérard (1761-1837) lived and trained with her sister and brother-in-law, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, in their Louvre residence from the age of fourteen; portrait painter Marie Éléonore Godefroid (1778-1849) initially grew up in the Louvre studio of her father and teacher, Joseph Ferdinand-François Godefroid; and Joseph Ferdinand-François himself continued the work of his mother, the painting restorer Marie-Jacob Godefroid.

Curtius’ waxworks Salon became a meeting place for intellectuals and, fittingly, Tussaud’s first work, as a teenager, was a portrait of Voltaire. It also became a popular venue for entertainment. In a 1784 print caricaturing the Salon, heads on stuffed torsos are switched as they go in and out of fashion (Fig. 3). A shelved repository provides several waxen options; one lies discarded on the floor. Onlookers are intrigued and engaged, the text beneath lamenting the French propensity for quickly changing fashions. These displays remained potent in visitors’ cultural imagination for decades.[5]

Fig. 3. Pierre Charles Duvivier, Changez moi cette Tête!, c. 1783. Etching, aquatint, brown ink, 20.4 x 27.7 cm. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2016.PR.13*). Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

The Revolution had a profound effect on Curtius’ Salon and his pupil. Following the fall of the Bastille, Tussaud modeled dozens of death masks, including those of Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette, and Robespierre. It seems that decapitated heads were often brought to her straight from the guillotine, although at times she went to the cemetery to seek out her subjects, on reputedly secret orders from the National Convention. The exact process remains unclear. Tussaud’s Memoirs, the main source of this information, is undoubtedly full of embellishments. Yet Curtius’s Salon was where many Parisians came to keep abreast of Revolutionary events and turns of fate, and contemporary sources affirm the visual accuracy of Tussaud’s heads.[6] As Curtius increasingly involved himself in Revolutionary events, it progressively fell to Tussaud to keep the Salon up to date. This necessitated being excessively aware of partisan turns, removing busts as soon as their subject lost favor—and rapidly modeling whoever replaced them in the turbulent political hierarchy.

Over these tumultuous years, Tussaud mastered a practice that aimed to take full advantage of wax’s lifelike nature. For her models of Revolutionary victims, Tussaud would have quickly made plaster casts of the severed heads, from which she made reusable clay molds. This technique ensured the exact replication of a sitter’s features and allowed her to make multiple portraits of each subject. When casting from life, Tussaud’s process was nearly identical, with the additional insertion of quills into a sitter’s nostrils, so that he or she could breathe while the plaster hardened.[7] Wax portraits could seem strikingly realistic, a vital visual element that endures in Curtius’ 1782 Self-portrait (Fig. 4). Moreover, Tussaud used real human hair and, whenever possible, teeth. Sitters meant to appear alive were given glass eyes. Her busts of the royal scaffold victims, eyes closed to appear serene, were not displayed until after her death. However, Tussaud and Curtius still exhibited other victims of the Revolution, often covered in fake blood for full effect.

Fig. 4. Philippe Curtius, Self-portrait, c. 1782. Wax and mixed media. Musée Carnavalet, Paris. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

By 1802, Tussaud sought new opportunities. Curtius had died in 1794, and she found herself supporting a lackadaisical husband and their two sons. During the brief Peace of Amiens (1802-1803), she accepted a business collaboration and crossed the Channel to England with her youngest son, a few wax figures, and her molds.[8] In her first surviving letter, from April 1803, she told her family “I must go alone and seek fortune,” attesting to both her unhappy partnership and increasingly entrepreneurial mind.[9] In February 1804, after successful shows in London, Edinburgh, and Dublin, Tussaud bought out her contract and embarked on a solo exhibiting career. Over the next thirty-three years, she took her waxworks exhibition to seventy-five towns in England, Scotland, and Ireland, permanently settling her artistic business in London in 1835. When she left Paris, Tussaud did not speak English, and had always worked in a domestic, family-based setting. How was she able to wield her wax artistry to forge a profitable and lasting independent career in a foreign country?

I would suggest that the unprecedented nature of Tussaud’s success was intimately connected to the medium of wax itself. Tussaud lived at a time when women were scarce in all professional vocations, and their public activities were intensely critiqued. For a woman to succeed as an artist, her choice of material was pivotal to her professional identity and success. The use of wax to depict royalty was not new in either country—Antoine Benoist had modeled Louis XIV in 1705, whereas in London, Mrs. Salmon’s popular waxworks show featured a representation of King Charles I on the scaffold from 1711, and the American sculptor Patience Wright had developed her own wax show and studio in 1775.[10] Catherine Andras, who exhibited several wax reliefs at London’s Royal Academy from 1801 to 1824, was appointed Modeler in Wax to Queen Charlotte in 1802. Yet waxwork was primarily seen as an amateur medium. It was never considered a mainstream artistic pursuit, nor readily celebrated as an artistic accomplishment. Rather, wax was often dismissed as a malleable material; requiring less strength and skill than other sculptural techniques, it was thought to be easier for women to mold.

Navigating an age marked by perpetual negotiations of public gender roles, Tussaud achieved unprecedented success by fusing her command of wax portraiture with a didactic bent. She used her French background and recent experiences to her advantage, presenting her traveling gallery as a venue for viewing famous Revolutionary figures almost literally in the flesh. She always exhibited portraits of Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette, Robespierre, Napoléon, and Joséphine, and visitors came in droves to walk amongst these uniquely natural impressions, conveyed so convincingly by the softness, translucency, and fleshly lifelikeness of the wax. As she explained in a letter to her family, “Nothing like them have previously been seen.”[11] Tussaud’s exhibition catalogues read like history books, detailing Napoléon’s military career alongside Charlotte Corday’s letters written from jail. She also used local newspapers to advertise the private sittings customary for traveling portraitists, once announcing, “The artist can also model from the dead body as well as from animated nature,” all “in the fullest imitation of life.”[12] From as early as 1819, Tussaud placed her own wax self-portrait in the middle of the gallery. Newspaper reports abound of visitors who mistook the figure for Tussaud herself, and felt snubbed by its lack of response.[13]

Tussaud’s ability to bring portraits to life was essential to her show’s lore, and wax was central to this process. By expertly wielding a material often stigmatized by the male-dominated Academic scene, she not only achieved more wide-ranging and financial success than almost any of her female contemporaries, she also established a unique form of art. Her work and its recognition suggests that her contemporaries perceived more fluid boundaries between hierarchies of media than is generally acknowledged, at least for portraiture. Even more, her story reveals vital means by which women could artistically, resourcefully, and professionally navigate the Revolutionary world.

Paris Amanda Spies-Gans, a PhD candidate at Princeton University, NJ, is writing a dissertation entitled Claiming a Visual Voice: How Female Artists Navigated the Revolutionary Era in Britain and France, ca. 1760-1830

[1] This episode is frequently cited with reference to Madame Tussaud. See, particularly: Tessa Murdoch, “Madame Tussaud and the French Revolution,” Apollo 130:329 (July 1989), 9-13; Helen Hinman, “Jacques-Louis David and Madame Tussaud,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 96 (December 1965), 331-338; Jean Adhémar, “Les musées de cire en France, Curtius, le “banquet royal”, les têtes coupées,” Gazette des Beaux Arts 92 (1978), 203-214; and, for the most detailed analysis, David McCallam, “Waxing Revolutionary: Reflections on a Raid on a Waxworks at the Outbreak of the French Revolution,” French History 16:2 (2002), 153-173.

[2] Of course, Tussaud features in several histories of waxworks, the most thorough of which is by historian Pamela Pilbeam. Former archivist Pauline Chapman’s several biographies on Tussaud are mainly narrative, and depend heavily on Tussaud’s own Memoirs, published in 1838. Dictated to Tussaud’s friend, the French-born British writer Francis Hervé, the Memoirs present many historically questionable accounts, including Tussaud’s claim to have spent years at Versailles as an art tutor to Princess Elisabeth, sister of Louis XVI. See: Pamela Pilbeam, Madame Tussaud and the History of Waxworks (New York: Hambledon and London, 2003); Anita Leslie and Pauline Chapman, Madame Tussaud: Waxworker Extraordinary (London: Hutchinson & Co. Ltd, 1978); Pauline Chapman, The French Revolution as seen by Madame Tussaud, witness extraordinary (London: Quiller Press, 1989); Pauline Chapman, Madame Tussaud in England: Career Woman Extraordinary (London: Quiller Press, 1992); and Marie Tussaud, Madame Tussaud’s Memoirs and Reminiscences of France, Forming an Abridged History of the French Revolution, ed. Francis Hervé (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838).

[3] Tussaud was born Marie Grosholtz in Strasbourg in 1761; her father, a soldier, had died just before her birth. She and her mother soon moved to Bern, where her mother worked as Curtius’ housekeeper. They moved to Paris with Curtius in 1765. In 1795, after Curtius’ death, she married François Tussaud (1767-1848), a civil engineer. Recent research has found that her father’s family worked as executioners in Strasbourg; this may partially explain her comfort with guillotine victims, and certainly adds an interesting interpretive layer (see http://television.telerama.fr/television/madame-tussaud-un-destin-grave-dans-la-cire,150582.php).

[4] He refers to her as “mon élève dans mon art.” “Testament de C. Curtius,” 14 fructidor an II (August 31, 1794), Archives de Paris, Minutier central des notaires. Transcribed and translated by Pauline Chapman in 1976 for Madame Tussaud’s, London.

[5] Carol Ockman argues that it even influenced Théodore Laborieu’s description of Ingres’s odalisques in 1855. Carol Ockman, Ingres’s Eroticized Bodies: Retracing the Serpentine Line (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995), 100-103, citing Laborieu, “Les peintures des beaux-arts” (1855).

[6] Tensions in Paris were high, and the Salon’s artists wanted their allegiance to be clear. Curtius even published a pamphlet in 1790 to affirm his (minor) role in the storming of the Bastille and commitment to the Revolutionary cause. Philippe Curtius, Services du sieur Curtius, vainqueur de la Bastille (Paris, 1790).

[7] For the process see Pilbeam, Madame Tussaud, 28; she further cites Edward V. Gatacre and Laura Dru, “Portraiture in Le Cabinet de Cire de Curtius and its Successor, Madame Tussaud’s Exhibition,” Biblioteca della rivista di storia delle scienze mediche e naturali 20 (1977), 617-638, extract from Atti del I congresso internazionale sulla ceroplastica nella scienza e nell’arte (Florence, June 1975); and Edward Gatacre and Jean Franser, “Madame Tussaud’s Methods,” Biblioteca della rivista di storia delle scienze mediche e naturali 20 (1977), 639-647, extract from Atti del I congresso internazionale sulla ceroplastica nella scienza e nell’arte (Florence, June 1975).

[8] An old friend of Curtius, Tussaud’s partner, Philipstal, had just renewed a lease at London’s Lyceum theatre for his Phantasmagoria, a magic lantern show. According to the terms of their initial arrangement, Philipstal was entitled to fifty percent of her profits, and was himself responsible for advertising and transportation costs. Yet, as Tussaud’s letters show, she received minimal help from her partner, even while she continued to reap and divide her earnings.

[9] Marie Tussaud to M. [François] Tussaud, Boulevard du Temple No. 20, Cabinet de Curtius, Paris, April 25, 1803 [dated: “London Le 25 avril L[‘]a[n] II]. Madame Tussaud’s, London.

[10] Charles Coleman Sellers, Patience Wright, American Artist and Spy in George III’s London (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1976); and Richard Altick, The Shows of London (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1978), 52-53.

[11] Marie Tussaud to Monsieur [François] Tussaud, Boulevard du Temple No. 20, Cabinet de Curtius, Paris, May 26, 1803. Madame Tussaud’s, London.

[12] Chapman, Madame Tussaud in England, 22, citing the Glasgow Herald and Advertiser.

[13] See, for example, Lincoln, Rutland and Stamford Mercury, July 22, 1819; Nottingham Journal, October 2, 1819; Leeds Intelligencer and Yorkshire General Advertiser, Editorial, May 8, 1820; Manchester Mercury, August 22, 1820.

Cite this note as: Paris Amanda Spies-Gans, “‘The Fullest Imitation of Life’: Reconsidering Marie Tussaud, Artist-Historian of the French Revolution,” Journal18, Issue 3 Lifelike (Spring 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1438. DOI: 10.30610/3.2017.8

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.