Animal, animality: this issue of Journal18 is devoted to a category of

being that stumped many eighteenth-century thinkers. How could something so

broad be reasonably and securely defined? Even in the Encylopédie’s entry on “Animal,” the word resisted definition, for

despite “the general idea of what we mean, […] there is not a single one that

constitutes the essence of the general idea.”[1]

Animals might be defined in opposition to what they are not, notably plants,

but even this exclusion proved problematic. The Encylopédie’s authors proposed that form, movement, perception,

relative sensitivity, and method of nourishment separated plants from animals,

though not always. The attempt to define a set of distinctive traits for animals

paradoxically led the authors to declare a “manifest impossibility of

reasonably excluding any living being from the animal class.”[2]

The acknowledgement that animals cannot be demarcated from other forms of life

and the fact that they are conceptualized as something akin to life itself

speaks to their pivotal role in shaping knowledge, experience, and humanity’s

perception of itself. In

eighteenth-century art and visual culture, visual representations of animals

served as a basis for humans to negotiate the boundaries of this dauntingly

expansive category to which they also belong.

Expanding on a recent “animal turn” in the humanities and social sciences, this issue of Journal18 explores particular instances of animal-driven forms of meaning in an array of visual objects produced in the long eighteenth century. Amy Freund and Michael Yonan look to the strangeness of French cats, examining the material and philosophical challenges they posed for Enlightenment artists and thinkers. Daniel Greenberg explores the birds of China, through an album that offers a space for considering the intersections of natural history, art history, and cross-cultural conceptions of avian life during the Qing dynasty. And in Catherine Girard’s article on Canadian caribou, it is the animal skin itself, made into coats and painted by Innu women, which offers a haunting, poetic meditation on human-animal relations.

In addition to these articles, this issue’s “Menagerie” of shorter vignettes includes animals ranging from the miniscule to the monumental. Patricia Simons focuses our attention on the visual poetics of elusive flies, while Meredith Martin examines an elephant monument to Louis XV as a methodologically and theoretically capricious beast. Alex Weintraub explores the ambiguity of avian liveliness in Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s dead birds, and lastly, Stephanie Triplett examines the use of classicizing animal motifs on the walls of an animal dissection theater. Pushing back against the idea of the animal as a mere foil for more significant human drama, together these contributions reassess the role of animals as the very actors, agents, and materials of art’s histories.

Issue Editor

Katie Hornstein, Dartmouth College

ARTICLES

Cats: The Soft Underbelly of the Enlightenment

Amy Freund & Michael Yonan

Innu Painted Caribou-Skin Coats, and Other Tales of Elusiveness

Catherine Girard

Taxonomy of Empire: The Compendium of Birds as an Epistemic and Ecological Representation of Qing China

Daniel M. Greenberg

MENAGERIE

Monstrous Assemblage: Charles-François Ribart’s Elephant Monument to Louis XV

Meredith Martin

Isabelle Pinson’s Fly Catcher (1808): Genre, Anecdote, and Pictorial Theory

Patricia Simons

Creaturely Classicism in Christian Bernhard Rode’s Tieranatomisches Theater Frescoes

Stephanie Triplett

On Girls and Birds: The Structure of Aesthetic Feelings, c. 1800

Alex Weintraub

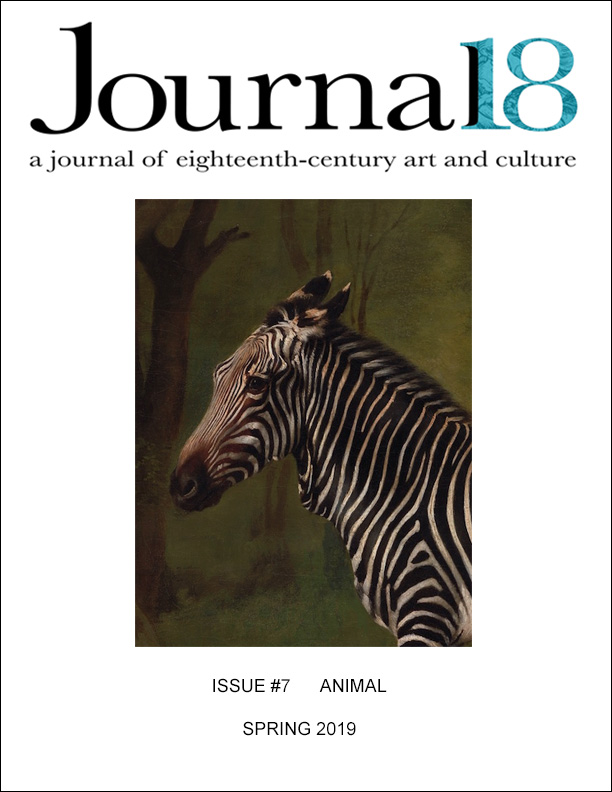

Cover image: George Stubbs, Zebra, 1763. Oil on canvas, 102.9 x 127.6 cm. Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven. Image courtesy of Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

[1] “Animal,” in Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, ed. Denis Diderot et Jean le Rond d’Alembert (Paris: Société typographique, 1778), vol. 2, 672.

[2] “Animalité,” in Encyclopédie, vol. 2, 686.