Art history has traditionally narrated the early modern city through the monuments and buildings that constituted its environment and with reference to its spatial distribution. This special issue invites readers to consider the city instead via the social: to think about the people who once inhabited those buildings, admired those monuments, those who shared the spaces and resources of the city, and the ideas, beliefs, and practices invested in and inspired by it.

For Aleksandr Bierig, the social is social life literally speaking, and that which the city must foster through clean air. In a close reading of Timothy Nourse’s 1700 critique of London’s coal-induced smog, and his proposal to purify the capital’s atmosphere by reverting to wood, Bierig shows that Nourse’s “restoration” acknowledged various trade-offs between social needs and industry but did not propose to turn back the clock, either socially or ecologically. Rather than retreat to pastoral, Nourse envisioned the relocation of industry to the city limits, as well as the plantation of an orbital forest to supply London. He viewed nature as a resource—in the modern sense of an object uniquely for commercial exploitation—of the good city.

Stacey Sloboda’s essay on London’s St. Martin’s Lane engages with the social on the scale and in the terms of neighborhood, a concept in which the built and the social are united. By following inhabitants of St. Martin’s Lane through rent registers and other sources, she explores the imbrication of artistic and artisanal practices that academies and art theory often obscure. Moreover, she complicates the binaries we draw to distinguish the modern and pre-modern city: between an older world of dense, low-rise housing and inward-looking community living, and the modern, outward-facing city produced by industrialization and migration. The St. Martin’s Lane school drew both some of its agents and some its artistic ideas from Europe and thought its taste modern.

Questions of place and emplacement are key also to Anne Hultzsch’s essay. However, she explores not the community and the rootedness associated with neighborhoods, but the individual’s embodied relationship to site. She reviews Sophie von La Roche’s writings on the city as “situated criticism,” situated both in the literal sense of point of view, and sociologically as a woman of a certain class. What distinguishes Hultzsch’s take on the social and sets it apart from late twentieth-century social and political histories of art criticism is her discussion of La Roche’s experience of the visual, and her use of biography to lay bare her subject’s identity in its intersectional complexity.

The two shorter pieces, each with a more historiographical focus, center on the figure of the urban observer. Richard Wrigley argues that the personage of the flâneur, normally characterized as disengaged and associated with the July Monarchy, had in fact originated in the political culture of the French Revolution, and as an effect of self-determined mobility within the city enabled by liberty. In so doing, he restores an essential political context to the phenomenon of flânerie that has long been obscured by its limiting association with the burgeoning consumer culture emblematized by the Paris passages. Sigrid de Jong, meanwhile, analyses the eighteenth-century literary trope of urban comparison. Situating such description in relation to current scholarly recourse to comparative history, she focuses on Paris and London in texts by Louis Sebastien Mercier and Helen Maria Williams, respectively. She suggests that their kind of explicitly situated subjectivity offers a privileged entry to the specifically social limitations and possibilities that structure real experiences of the city.

By variously answering such historical questions as—How did the city make room for sharing (air, ideas, experiences, space)? How did different kinds of urbanites (writers, artists, tourists, women) use, exploit and otherwise appropriate urban space? And how were the limits and possibilities of city social life made sensible in word and image (maps, views, description)?—these case studies collectively propose a richer yet less stable view of the proto-modern European city.

Issue Editors

Katie Scott, The Courtauld Institute of Art

Richard Wittman, University of California, Santa Barbara

ARTICLES

Restorations: Coal, Smoke, and Time in London, circa 1700

Aleksandr Bierig

St. Martin’s Lane: Neighborhood as Art World

Stacey Sloboda

The City “en miniature:” Situating Sophie von La Roche in the Window

Anne Hultzsch

SHORT PIECES

The Revolutionary Origins of the Flâneur

Richard Wrigley

The City and its Significant Other: Lived Urban Histories beyond the Comparative Mode

Sigrid de Jong

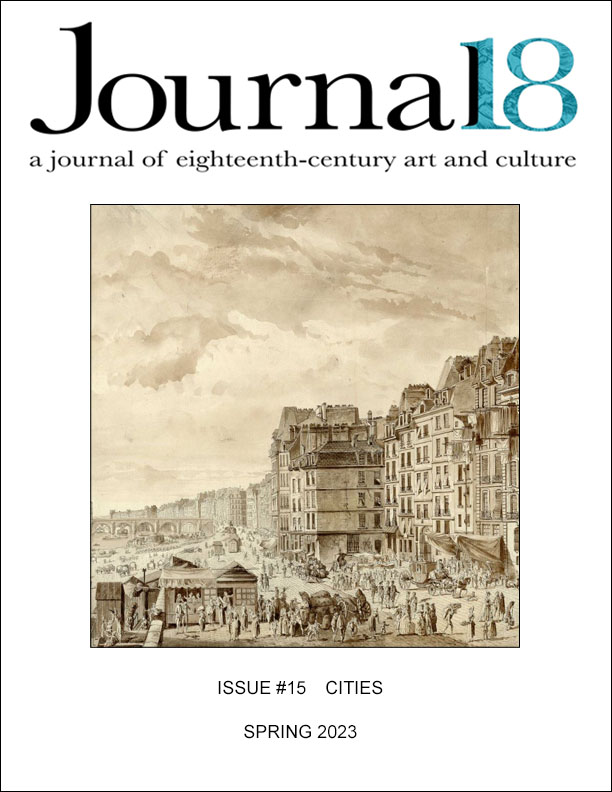

Cover image: Unknown artist, “Vue intérieure de Paris representant le port au blé depuis le marché aux vaux [sic] jusque au pont Notre Dame,” 18th Century. Pen drawing and brown ink wash on paper, 37 x 62.5 cm. Image source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.