Aleksandr Bierig

Early modern London was the planet’s first coal-fired city. While the causes and timing of its transition to fossil fuel are still debated, historians have argued that the change was initially triggered in the early seventeenth century, when apparent timber shortages began driving up firewood prices in the metropolis. At the same time, the chance existence of waterways near the coalfields of Durham and Northumberland, three hundred miles north of London, afforded the possibility of shipping fossil fuel along the eastern English seaboard during a period of highly constrained transportation. While coal had been extracted from these areas for centuries, its scale was always limited; coal remained a specialty fuel, considered appropriate only for heat-intensive activities like firing limekilns or blacksmithing. But in the decades around 1600, necessity and circumstance compelled Londoners to dramatically expand their consumption. The city adopted coal—previously considered too dirty and noxious for widespread use—as its general fuel.[1]

As London embarked on its experiment in fossil fuel use, how would coal-fired cities become different from previous ones? First and foremost, fossil fuel provided London with a novel and powerful source of heat. On the whole, summarizes Derek Keene, coal “endowed London with a virtually unlimited source of energy to support its physical growth.”[2] To take one striking example, coal was crucial to the reconstruction of London in brick following the Great Fire of 1666; in the aftermath of the destruction, as many as 100 million bricks were manufactured each year, a scale and speed of production that would have been impossible with any other fuel.[3] From a broader perspective, Britain’s adoption of fossil fuel allowed for an unfamiliar, indeed unprecedented, type of urban, economic, and demographic growth.[4]

Beyond these sweeping changes, which unfolded over decades and generations, the most infamous and immediately perceptible consequence of London’s early coal use was smoke. Above all, urban coal smoke was sensible to sight, smell, and taste. In one of the earliest evocations of London’s pollution—Fumifugium, or, The inconveniencie of the aer and smoak of London dissipated together with some remedies humbly proposed (1661)—botanist and diarist John Evelyn expressed his “Indignation” that London, “this Glorious and Antient City,” should suffer a condition that “darkens and eclipses all her other Attributes.”[5] In his pamphlet, Evelyn seemed particularly concerned with the effects of pollution on human health, anticipating another theme that would persist for centuries. He claimed that Londoners were subject to the “disordering [of] the entire habits of their Bodies; so that Catharrs, Phthisticks, Coughs and Consumptions rage more in this one City than the whole Earth besides.”[6] Coal smoke, he noted, also seemed to affect other living things. When coal supplies temporarily ceased during the English Civil War a decade earlier, Evelyn recalled that “Gardens and Orchards planted even in the very heart of London, were observed to bear such plentiful and infinite quantities of Fruits, as they never produced the like either before or since.”[7] London’s smoke, like its use of coal more generally, was aberrant, and it produced aberrations. The city’s early entanglement with fossil fuel had enabled explosive growth, but it also seemed to disorder life in the city.

These themes are well known. Many scholars have explored how urban pollution became the sign of London’s anomalous source of energy, offering visible evidence of the unplanned consequences introduced by the widespread consumption of fossil fuel. William Cavert, who recently published the definitive history of pollution in early modern London, has shown how, as early as the seventeenth century, “smoky air became a symbol of urban life.”[8] His comprehensive scholarship complements scores of studies on urban pollution in London, which have tended to focus on its regulation, its effects on health, and its presence in literary culture.[9] These writers cast atmospheric pollution as a hallmark of what Cavert calls the city’s “early modernity,” prefiguring a more general condition of urban life in the modern period.[10]

The repeated use of the word “early” here should remind us that, before other places adopted coal in the nineteenth century, London’s pollution was unlike anything else in the known world. It was also the result of circumstance. The city lies in the Thames River valley, providing the topographical setting for a phenomenon known as “temperature inversion.” As cold air becomes trapped beneath warm air, it creates a lingering fog; in London, this atmospheric mist combined with the sulfur and particulate matter that was released from burning bituminous coal. In addition to visible pollution, this mixture creates the compound sulfur dioxide, an acid that corrodes surfaces of all kinds. Retrospective calculations by Peter Brimblecombe and Carlota Grossi estimate that the concentration of pollutants in London’s air exceeded modern levels as early as the mid-seventeenth century.[11]

If many worried about London’s pollution—writers, natural philosophers, physicians, and politicians, as well as the scientists and scholars that followed in their wake—very few imagined that anything could be done about such a pervasive and entrenched problem. The two authors discussed in this essay were the exception and among the earliest to do so. Both John Evelyn and his lesser-known contemporary Timothy Nourse began from the problem of London’s smoke, only to find themselves pulled into acts of urban planning. They both devised schemes to repair the city’s pollution and, in doing so, expressed a kind of early environmental nostalgia. Writing towards the end of the seventeenth century, Evelyn and Nourse both dreamed they might restore the city and its air to a time before London had embarked on its fossil-fueled urban life.

Their proposals, however, were very different. Evelyn’s well-known and well-studied pamphlet, Fumifugium, put forward a spatial solution: he proposed reorganizing London by relegating smoky industries outside of the city, beyond the poorer eastern edge of the metropolis. By contrast, Nourse’s proposal, “An Essay upon the Fuel of London” (1700), outlined a material solution, a scheme to restore wood as London’s primary fuel. If Evelyn’s text is well known as a formative historical example of environmental and urban planning, in this essay I will argue that it was Nourse’s plan that showed more clearly how the coal-fired city presented new problems, which were less about the appearance of space than about the composition of a new, fossil-fueled urban metabolism that had social, spatial, and temporal consequences.[12] Nourse implied that it was only by attending to this material directly—by restoring wood as the fuel of the metropolis—that London might be returned to a more manageable state.[13]

A focus on Nourse’s unusual plan, in turn, offers a different view of the implications of coal smoke: of what pollution ultimately meant for the direction and fate of the city. Opposed to the predominating concerns with the aesthetic and medical consequences of smoke, Nourse’s text dwelled on a stranger and less immediately sensible problem: he drew attention to the ways in which coal’s pollution seemed to speed up the material decay of the city, dissolving the surfaces and connective tissues of its built environment—smoke corroded London’s stone facades and ate away at mortar joints and iron hinges. Indeed, smoke seemed to attack any object of human fabrication, damaging buildings, furniture, tapestries, and clothing. If the visibly polluted air of London and its effects on human health have been the subject of much historical interest, this kind of progressive material disintegration was more difficult to capture. It did not merely affect the eyes and lungs, but it disrupted the reliability of time itself.

In exploring these ideas, Nourse’s essay suggested that coal had introduced a new kind of inorganic, artificial ecology that would prove fateful for this city and, eventually, all others.[14] Before the modern steam engine, before coal-fired iron production, before canals and railways and fossil capital, his attention to the interaction between coal, smoke, and the built environment suggested that there might be an intrinsic relationship between fossil fuel and the unruly temporal relations that it unleashed. Even at this first, urban scale, the unfamiliar cycles of production, consumption, and destruction set off by coal use had, in a sense, accelerated the speed of time.

Designs on the City: Spatial and Material

Before exploring Nourse’s essay, however, it is worth reviewing John Evelyn’s earlier text on coal, smoke, and the shape of the city. Evelyn’s Fumifugium is rightly seen as a seminal text of urban planning and, like most acts of planning, it emerged from a close connection with political power. The twenty-six-page essay appeared in 1661, the first year of Charles II’s restoration to the English throne, and it was directly addressed to the reinstated king.[15] In offering a response to London’s pollution, the royalist Evelyn imagined that political control over the city would be restored, just as the monarchy had been the year before. Fumifugium, according to this reading, was not so much an urban design as an articulation of an elaborate political allegory. Evelyn’s smoke, argues historian Mark Jenner, served as “a metaphor of the political disorder of the Interregnum and his proposal was intended as a “panegyric to the new regime.”[16] Reinstating a smokeless urban order would give credit to the king’s restored position.

If Evelyn interpreted London’s pollution as a political problem, he also understood it as a distinctly spatial one. Fumifugium began by recounting how a wave of “presumptuous Smoake” had infiltrated the king’s palace at Whitehall, flooding in until “all the Rooms, Galleries, and Places about it were fill’d and infested.”[17] It was this violation of physical space, directly imposing on the body of the monarch, that set the stage for his essay. Evelyn cast London’s smoke as a challenge to royal authority and, in response, he proposed that the king should eliminate pollution throughout the city as proof of his power.

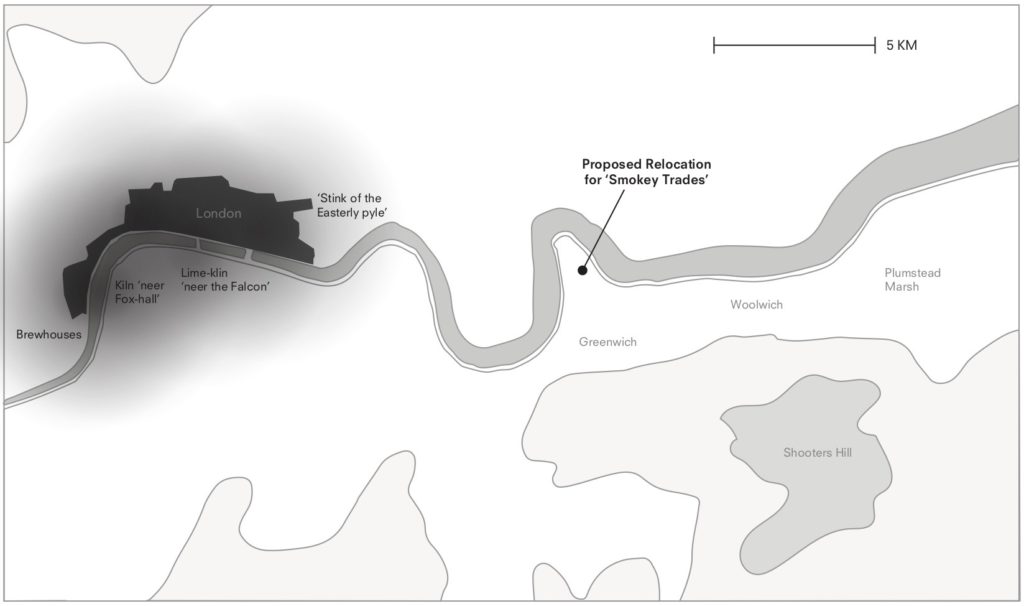

Like his motivating concern, Evelyn’s solution was also spatial: he proposed moving what he called the “smokey trades” beyond the southeastern edge of the city, as can be seen in a diagrammatic map (Fig. 1). London’s “Brewers, Diers, Lime-burners, Salt, and Sope-boylers,” he explained, were located along the Thames River close to the city center. One of their “Spiracles alone,” Evelyn judged, “does manifestly infect the Aer, more than all the Chiminies of London put together besides.”[18] In fact, he was probably wrong to single out these sources as the primary cause of the city’s pollution; despite the spectacular emissions generated by workshops and breweries, it is likely that domestic fireplaces accounted for the vast majority of emissions.[19] Evelyn’s reasoning, however, underscored the spatial and aesthetic nature of his inquiry. The smoke coming from intensive coal use was concentrated and visible in the city center. According to this logic, those activities would need to be removed.

Evelyn did not go into detail regarding how such an enormous industrial transfer might be implemented or who it would affect. He briefly imagined that his plan would create more work for those “Thousands of able Watermen” working the small rivercraft on the Thames—if manufacturing moved eastward, the workers moving goods along the river would find even more employment, he wrote, bringing “Commodities into the City.”[20] But the broader implications of this immense spatial reorganization were left unexplained. Evelyn’s aim was to sever the visible co-dependence of the city and its dirty fuel, not to explain the interactions and complications engendered by coal use. Like so many later acts of urban planning and industrial zoning, his proposal imagined a spatial segregation of production and consumption.

As a counterpart to this displacement, Evelyn also proposed surrounding the metropolis with newly planted fields of “the most fragrant and odoriferous Flowers … aptest to tinge the Aer upon every gentle emission at a great distance.”[21] It was not enough, in other words, simply to remove pollution from central London; Evelyn also wanted to renovate the air itself. In his reformed city, appearance would be paramount, and his design aimed at the top of the social hierarchy, at the royal court and its elite audiences to whom he addressed his essay. Had the reforms been enacted, the jumble of wharfs and factories that littered London’s riverbanks would have been replaced by grand residences for the city’s elite—a plan, Cavert summarizes, “quite literally, to gentrify London.”[22]

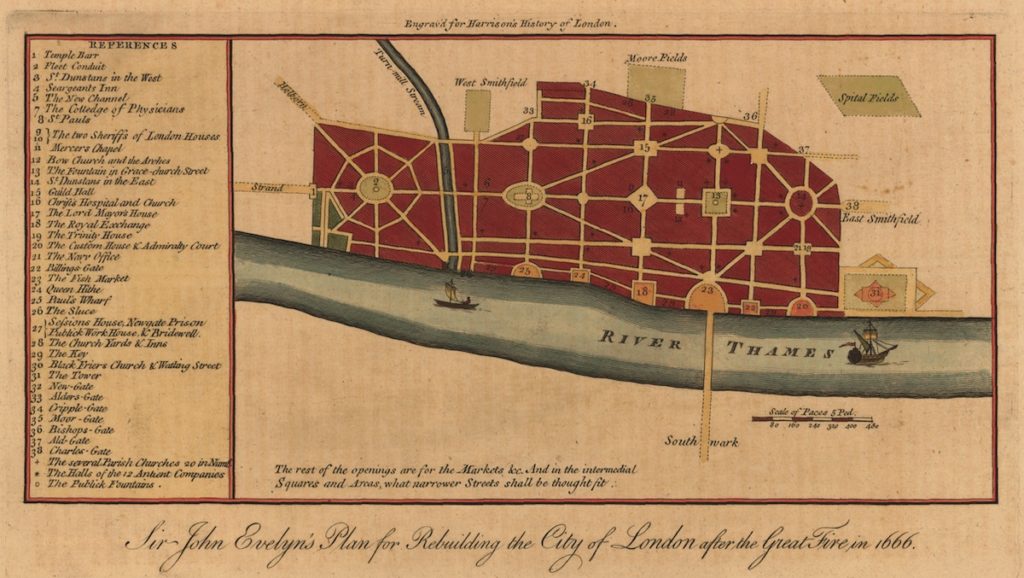

These ideas resonated with Evelyn’s enduring belief in the political importance of architecture and urbanism. He admired the aesthetic absolutism of Louis XIV’s France, which he had witnessed firsthand during the English Civil War. One of his earlier essays, A Character of England (1659), offered ideas and plans for a redesigned London, beginning from another diagnosis of the city’s ills.[23] In that essay, a fictional French visitor complained that in ramshackle London, “the buildings are as deformed as the minds and confusions of the people.”[24] Likewise, following the Great Fire of 1666, he offered a plan to rectify the chaos of the central city, straightening its streets and clearing out its warrens of alleys and byways (Fig. 2). Everywhere he looked, Evelyn seemed to find a world that needed to be brought into order.

Some thirty years later, London’s smoke once again prompted a writer to imagine an immense reform. Much had changed during the intervening decades—a devastating fire and a deposed monarch—but the city’s pollution remained persistent. In response, Timothy Nourse’s “An Essay Upon the Fuel of London” imagined planting an immense forest to surround the metropolis, a new supply source that aimed to reinstate wood as London’s fuel. Instead of reorganizing the space of the city, as Evelyn had proposed, Nourse argued that its pervasive smoke could only be drawn back through a deliberate material restoration, a return to wood. While Evelyn had briefly contemplated this same idea, he quickly dismissed it: “to talk of serving this vast City (though Paris as great, be so supplied) with Wood [would be] madnesse.”[25]

As we will see, Nourse took this “madnesse” seriously, methodically working through the requirements of his plan. If London’s material relations had been disordered by the importation of coal from hundreds of miles away, Nourse imagined that his proposed forest around London would restore a legible order. Once wood was restored, the long-distance supply chain that provided fossil fuel to the city would be replaced by a direct relation of interior and exterior, city and hinterland, consumers and producers. At the same time, Nourse’s plan also underscored the immense differences that already existed between coal and wood. In comparing the two fuels, he revealed how difficult, if not impossible, it would prove to find an adequate substitute for the surplus energy of fossil fuel.

What led Nourse to this unusual idea? Compared to the well-known Evelyn, Nourse’s motivations are less clear. Little is known about him. He was, according to one account, from an “old Royalist family which had formerly held estates in Bucks, Oxford and Hertford.”[26] He studied at Oxford, became a preacher, and wrote about religious topics. His “An Essay upon the Fuel of London,” however, appeared at the end of a long treatise on agricultural improvement, which was initially published in 1700, the year following his death.[27] Despite appearances, however, it is precisely this unusual context that helps explain aspects of Nourse’s perspective and raises a number of troubling questions about planning and conservation in its wake.

Understanding Nourse’s proposal to return from coal to wood, in other words, requires a detour into the content and contexts of the book it appeared in: Campania Fœlix, or, A Discourse of the Benefits and Improvements of Husbandry (1700). Like many other contemporaneous works on agricultural management, it was a profoundly conservative text, offering fifteen chapters of advice on how to manage a countryside estate. Nourse offered a catalogue of techniques to both improve agricultural yields and, perhaps more importantly, to conserve the social hierarchy of the rural world. In his view, the country landowner, the tenant farmers who paid rent, and the poor landless cottagers each had their established place in the social order.[28] This hierarchy, however, was not stable but fragile; it depended on incentives and designs imposed from above. “An Essay upon the Fuel of London” can only be understood in relation to these larger themes—in particular, Nourse’s abiding interest in the relationship between human intentions, material design, and the social consequences that such designs gave rise to over the course of time.

Campania Fœlix was a late entry in a long tradition of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century texts on agricultural “improvement,” which advised landowners how best to supervise their rural holdings. As in many of those earlier works—such as Walter Blith’s defining pair, The English improver (1649) and The English improver improved (1652)—Nourse’s recommendations were founded on a belief that to improve one’s estate was to carry out God’s work.[29] As he explained in his preface: “The same spot of Ground, which some Time since was nothing but Heath and Desart, and under the Original Curse of Thorns and Bryers after a little Labour and Expence, seems restor’d to its Primitive Beauty in the State of Paradise.”[30] For Nourse, as for his improvement-minded predecessors and contemporaries, agricultural management was understood as a path towards the re-creation of a prelapsarian abundance.

Beyond these grand beliefs, however, most of Campania Fœlix detailed smaller problems. It offered pages of advice on topics like the rotation of seasonal crops or how to best synchronize the pollarding of trees. Most notably, Nourse implored landlords to think through the intricate, cascading social effects of what we might now call their design decisions.[31] Take his fourth chapter, “On Fences.” When building fences for fields “near Cities,” he explained, it was better to use “Banks of Earth” rather than hedges. Near urban areas, “the great Numbers of Poor who inhabit the Out-skirts, who upon all Occasions, and especially in cold Weather, will make Plunder of whatsoever is combustible.”[32] If hedges of hazel or holly were liable to be ransacked for fuel by the urban poor, Nourse advised that landlords could plan ahead and protect their investment by building what he called “Dead Fences”—either ramparts made of earth and stone—or by digging ditches to mark the edge of a property. The very substance of a constructed boundary, he implied, carried a choreography of incentives that would have to be carefully and deliberately considered.

The larger challenge Nourse described, which would reappear in his discussion of London’s coal, was how to strike a delicate balance between private property and the public good, between individual interest and social stability. Those who owned land held a privileged position, but it was one that relied upon other people and other things. In another chapter, he suggested that landlords should build cottages for their landless laborers, depicting these dwellings as self-contained, dignified units: “its little inclosures lying round about it … every such Cottage seems to be an Epitome of a more Voluminous Farm.” While the rights to own property were sacred, they did not exist in isolation; “when a particular Man’s Concerns is so twisted with that of others,” he wrote, “all must either sink or swim together.”[33] This led to one of Nourse’s broadest interpretations, which outlined a complicated role for the rural poor within a large story of national interest. While he mistrusted commoners, he also saw the rough independence of the rural laborer as an asset and even a national advantage—in his view, the unruliness of the rural poor also made them ideal military recruits.[34] For reasons small and large, then, the landowner should cautiously respect the commoner, incentivizing, but not coddling, the landless laborer. This approach would be embodied in ditches and fences and cottages. The social and material order of things were intertwined.

The most vivid example of Nourse’s method of social management through material design appeared in the first essay appended to the main text of Campania Fœlix: “An Essay of a Country-House.” In this text, Nourse painstakingly described the architecture and planning of a countryside villa. Landscape historians have discussed this essay, placing it in the long tradition of the idealized rural residence from Varro to Palladio.[35] The essay also drew on what architectural historian James Ackerman called the “villa ideal”—the villa as a particular product of the metropolitan idealization of the pastoral world.[36] Nourse hinted at this lineage. Unlike the rest of his book, the “Country-House” was not intended for the manager of an agricultural estate. Instead, he imagined the design for an absentee urban landowner, fit “to lodge a Nobleman endu’d with ample Fortunes and a vertuous Mind,” a place to retreat from the city in “the solid and serene Enjoyments of the Country.”[37]

Nourse offered no drawings of this structure, but he did describe the design in thousands of words of exhaustive detail. The width of the main staircase would extend eight feet, with “the Rails of the Stairs [to be] laid in Oil to prevent Rust.” The windows on the upper floor should number fourteen on the front façade and seven on the lateral side. Three separate gardens would flank the house and extend into the landscape. He even suggested that “a little Town or Village” should be designed at the perimeter of the estate, a model community filled with “all sorts [of] Artificers and Labourers, which any Nobleman’s House can stand in need of”.[38] This anticipated the form known, many decades later, as a ferme ornée, or ornamental farm imagined as a kind of stage set for its wealthy owner.[39]

At first glance, this elaborate description seemed unburdened by the complex rural social structures explored through the rest of Campania Fœlix. The “Country-House” would cast a willful, dominating design over the landscape. In the last few pages of his essay, however, Nourse introduced an alternative to this vision that seemed at odds with what he had taken thousands of words to construct. After pages and pages of intense description, Nourse suddenly compared the plan to King Solomon’s “stately Palaces” in Ecclesiastes. Grand projects like the “Country-House” might at first appear “divinely inspir’d,” but “all such Delights are Vanity, as are all other contrivances and enjoyments whatsoever compar’d with what is truly durable and solid.”[40] Those who could not afford an extravagant villa, he wrote, might instead build a “little, well design’d House, neatly kept,” a structure that would embody the small comforts of “that middle Region of Happiness which lies above Oppression and Necessity, and below the Menaces and Storms to which higher Fortunes are expos’d.”[41] Rather than monumentalizing power, the landowner’s house could promote a virtuous, unassuming modesty. Architecture, in these terms, might mediate the social tensions on the agricultural estate. The landowner’s house could become another instrument to maintain the fragile order of the rural world.

Coal’s Urban Ecology

Nourse’s interest in the social implications of spatial and material design reappeared in the concluding text of his book,“An Essay upon the Fuel of London.” Here, he positioned himself between city and country, and perhaps it was this outside perspective that allowed him to envision the replacement of the city’s fuel. He aimed to turn the teeming, polluted metropolis into a place of deliberate natural and social management. He saw the city as if it were an estate.

As in his “Country-House” essay, Nourse began his closing text with a grand testimonial, celebrating London’s wide streets, its central river “cover’d always with such Ships laden with inestimable Riches,” and its many monuments of such “Greatness and Solidity, as will not easily be out-fac’d by Time.” Then, once again, he reversed course. Of all the cities in Europe, he continued, “there is not a more nasty and unpleasant Place.” He mentioned a litany of “Disorders”—excessive liquor, expensive food, and “Irreputable Traders” —but arrived at one problem that, he wrote, “if redress’d would extreamly Contribute to the Benefit and Beauty of this City; and if continu’d, will leave it expos’d to many fatal Inconveniences.” The potentially fatal issue was, naturally, the burning of coal and its attendant smoke. “This indeed is that one great Nuisance which sullies all the Beauties of the City,” Nourse wrote, noting that coal’s pollution “may be seen, felt, smelt, and tasted at some Miles distance, so obvious is it to all our Senses.”[42]

Though he began with the sensible and perceptible effects of coal smoke, Nourse seemed less concerned with human bodies than with inanimate things—how the very material of the city was undermined by pollution. This revolved around the corrosive compound produced by burning coal—later named sulfur dioxide—which insinuated itself into the materials of the metropolis, disintegrating them with an astonishing speed. Evelyn had also described this problem when he wrote that the city’s pollution left “a sooty Crust or furr upon all that it lights, spoyling the moveables, tarnishing the Plate Gildings and Furniture, and corroding the very Iron-bars and hardest stones with those piercing and acrimonious Spirits which accompany its Sulphure.” Physical things subjected to this atmosphere, Evelyn estimated, decayed “more in one year, then expos’d to the pure Aer of the Country it could effect in some hundreds.”[43]

London’s coal smoke seemed to accelerate time’s work, a temporal disruption that became particularly evident on the buildings of the metropolis. Nourse’s detailed description of this phenomenon is worth quoting in full:

And such truly is the Corroding Quality of this Smoak, that the hardest Things in Nature, or made by Art, cannot resist it; witness the Bars and Casements of Windows, the Balconeys, with sorts of Iron-work, which though never so well Oil’d and Polish’d, will in a few Years become Eaten and Mouldring with Rust, and must after a short Time be renew’d to become fresh Fuel for this all-devouring Smoak. The Stones themselves run the same Fate … eaten away peel’d and fley’d as I may say to the very Bones by this hellish and subterraneous Flume. … ’Twere endless to reckon up all the Mischiefs which Houses suffer hereby in their Furniture, their Plate, their Brass and Pewter, their Glass, with whatsoever is solid and refin’d, all which are Corroded by it. … Nay so piercing is this smoak, that it works itself betwixt the joints of Bricks, and eats out the Mortar; so that what was Fresh and Beautiful Twenty or Thirty years ago, now looks Black, Old and Decay’d […][44]

If London’s visibly polluted air has long served as the most noted register of the city’s precocious coal-dependence, this smoke perhaps obscured another, more elusive index: the accelerated wearing-away of stone, mortar, iron, and fabric. As pollution compromised the presumed solidity of architecture and other objects of human manufacture, the larger implications of coal use became evident. Fossil fuel had upended the physical stability of the city, disrupting the reliable and familiar rhythms of a wood-based energy system. Its smoke attacked not just the durability of materials, but also challenged the underlying assumption that things would stay the same—the ideological connection, as Elaine Tierney has suggested, between “permanence and progress.”[45] Coal undermined the expectation that tomorrow would, in some sense, look like yesterday.

Where Evelyn diagnosed a visually and spatially disordered world, Nourse recognized how coal use had given rise to a set of recursive, spiraling relations that unfolded over time—what we would now refer to as feedback loops.[46] For instance, he identified a recursive relation between visible pollution and the need to burn fuel. London’s coal smoke was particularly bad in winter months, meaning that “the force of the Winter-Sun is not able to scatter” and the city’s inhabitants were consistently cast into darkness, “totally depriv’d of the warmth and comforts of the Day.” In response, Londoners were compelled “to make more Fires than ordinary, so that the more Fire the more Smoak; and the more Smoak the more need of Fire.”[47] Nourse also noted that the material disintegration caused by pollution had necessitated a different and more constant kind of physical maintenance of the city’s architectural fabric. Coal smoke’s rapid decay meant that “once in an Age or Two there must be Rebuilding, or continual Repairing in a manner the whole City.”[48] Though he admitted that coal was a more concentrated fuel—“one Chaldron of Coal will yield more heat than Three or Four Loads of Wood”—he questioned whether the costs of this dense power were too extensive.[49] If coal provided an easy and ready heat, “so it is as true too,” Nourse wrote, “that the Dammage sustain’d by a House in London, or any Figure or Trade, by the smutty smoak of the Coal, is triple to the extraordinary Charge such a House would ly under, were it obliged only to make use of Wood and Char-coal.”[50]

If these consequences affected every house and trade, they also left their mark on the city’s central monuments—most notably, St. Paul’s Cathedral, then being reconstructed by Christopher Wren (a project paid for, in part, by a tax on coal imports into London).[51] He warned that the cathedral “so Stately and Beautiful as it is, will after an Age or Two, look old and discolour’d before ’tis finish’d.” Its intricate details, Nourse continued, had only provided more surface area to become “furr’d and sooty by the Smoak sticking to it, and in a short time be defac’d.”[52] In this atmosphere of decay, he concluded, it would be “impossible for any Man to live sweet and clean, to appear polite and well-adjusted amidst so many inevitable inconveniencies, without a vast Expence.”[53] Smoke seemed to attack all things “solid and refin’d”; the construction of a stable material world was difficult to conserve in the face of coal’s destructive effects.

The deeper irony was that coal’s energy had allowed for the fabrication of more solid things than ever before. It fueled a rapid increase in the production of materials that had granted a new physical permanence to the city—its bricks, mortar, glass and, later, iron. What Nourse revealed was that smoke ate away at the very things that coal had helped produce. Held within the frame of this first coal-fired city, fossil fuel had unleashed dense and intensive feedbacks of creation and destruction. The solid objects afforded by coal’s energy could not withstand its corrosive air. Though this relationship was not a straightforward, reciprocal one—an equal and opposite reaction—there was some sense in which the things that coal had given to London, its smoke took away.[54]

Architectural historians writing about later developments have commented on the material decay caused by modern pollution. In different studies, Timothy Hyde, Edward Gillin, and Jorge Otero-Pailos have each shown how the problem of pollution informed and challenged notions of legal, scientific, and aesthetic judgment in the nineteenth century, inciting ideas to reform the selection of building materials, architectural design, and aesthetic judgment to deal with the accelerated decay of coal smoke.[55] In those later episodes, however, pollution had become a necessary consequence of fossil-fueled modernity, whereas for Nourse, coal smoke remained a specific, local phenomenon. Since pollution and its effects were, circa 1700, more unusual, perhaps they were easier to recognize in their full implications. Perhaps this is why, in contrast to the reactive measures offered later—to regulate emissions, for instance, or to find a stone or chemical finish that might withstand the damaging effects of pollution—Nourse could still imagine confronting the problem at its root.

Keeping Time

Nourse’s diagnosis of coal’s cascading consequences—the unfamiliar, artificial ecology that fossil fuel had already generated by the end of the seventeenth century—led to his radical proposal to replace coal with wood. Where Evelyn imagined fields of flowers as urban ornaments, Nourse presented a distributed plan that encompassed natural and social effects. Where Evelyn’s spatial scheme stood as a reflection of royal authority, political circumstances had changed. Nourse suggested his planned forest would only be possible through an Act of Parliament, since “without the All-mightiness of a Parliament no Great and Public Work can ever come to any Maturity.”[56]

He worked through the material requirements of his idea. “To understand what Quantity of Fuel may be sufficient for this great City,” Nourse wrote, “we must enquire into its Bigness, the Number of its Inhabitants, and the Circumstances of the Climate.”[57] How many people lived in London, and how much coal did they actually burn? How could its dense power be replaced by the less potent heat provided by firewood? Nourse sketched out rough guesses, approximating the population of London, the number of chimneys in the city, and, from that estimate, the extent of the forest that would be needed to grow enough wood to meet demand. Historians discussing Nourse’s proposal have pointed out that these calculations placed him within an emergent trend of large-scale quantification. Nourse wrote around the same time that early practitioners of political arithmetic like William Petty and John Graunt attempted to capture city and nation in quantitative form. These calculative efforts also followed others who had tried to quantify estimated yields, tallying the expected output of managed forests and fields.[58]

Precise statistical estimation, however, was not the point of Nourse’s essay. His estimates were informed guesses and probably not particularly accurate. More striking was the way in which, just like his analysis of the unfolding consequences of coal pollution, he followed his reasoning both forward and backwards in a concatenation of accounts, each one informing the next in a chain. He did not simply attempt to estimate statistical totals, but constantly translated between them: London’s population was approximated in order to extrapolate aggregate fuel use; this number, in turn, informed how much woodland would be needed to replace coal’s heat, which itself depended on expected forest yields. Rather than offering a detailed quantitative assessment, he sketched the complex artificial ecology that coal had already generated. Wishing to draw it backwards, he then outlined his alternative vision of a return to wood and tried to imagine what social and natural relations this restoration would bring about.

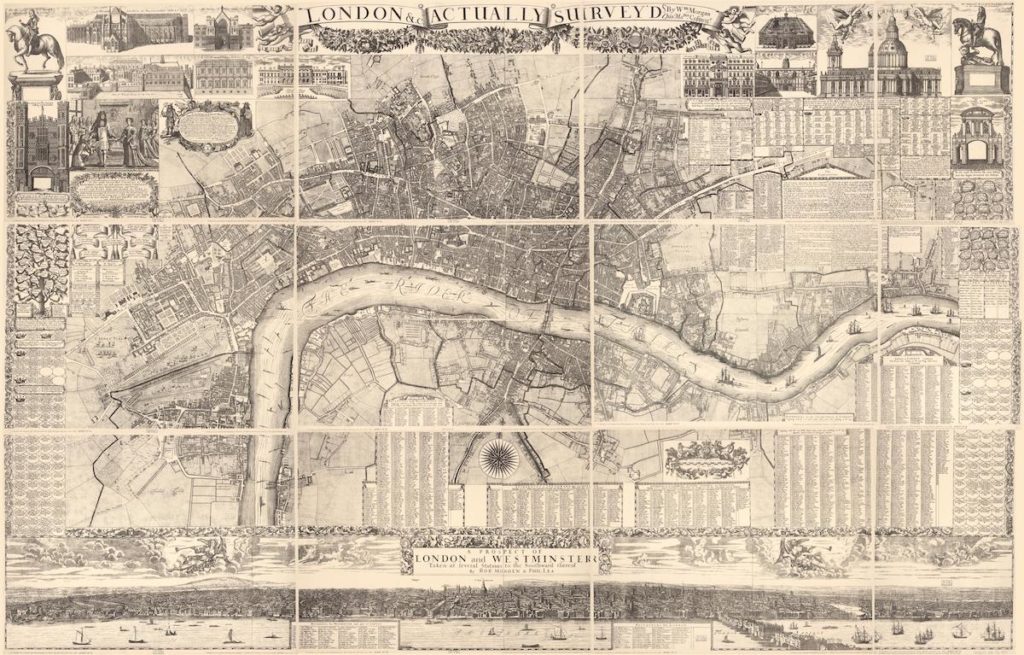

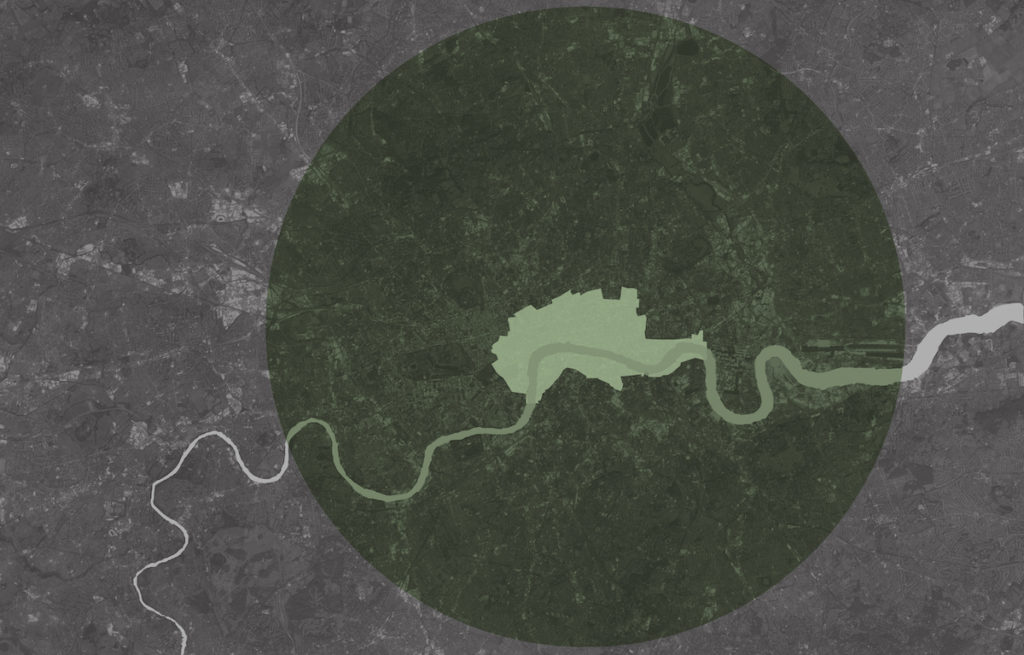

In the end, he projected that a managed forest around the perimeter of the metropolis— “about Sixty Thousand Acres of Land well planted”—would be able to provide enough fuel for the city’s needs.[59] Compare this to William Morgan’s 1682 map of London, which indicates that the built-up area of the city at this time occupied roughly 2,000 square acres (Fig. 3). Nourse was proposing a woodland, in other words, that would extend nearly thirty times larger than the city itself. Superimposing this territory over a satellite image of modern London shows that the forest would have taken up an area nearly equivalent to the whole of the present-day city, while only designed to provide enough firewood for five percent of today’s population (Fig. 4).[60] In sum, Nourse’s counter-geography of fuel aimed to reinstate wood, but in fact it ended up revealing how decisive the surplus energy of coal had been in shaping London. His project showed, in effect, how unnatural the metropolis had already become.

In the remainder of “An Essay upon the Fuel of London,” Nourse tried to fill in the gaps that his design seemed to leave open, to show that a well-managed wood supply could provide the same power as coal, without its increasingly evident environmental costs. As with his guidelines for estate management, his scheme to plant thousands of acres of woodland simultaneously affected both the natural and social worlds. Scores of laborers would have to tend to the woodlands, maintain its pollarding, and manage the transportation of firewood into the city. Once again, he saw an opportunity for social and natural management. So much work would result from the continuous maintenance of these forests, he argued, that every hundred acres would “very well Employ and Maintain Four Families for ever.” Through this employment program, he concluded, “the poorer sort of People will be double gainers by the Bargain.”[61] Nourse had imagined a vast plantation filled with (if we follow his estimate) 2,400 families dotted through the forest, tending to its continuous cultivation. Worried that the woodland might become a target for “Thieves, and Robbers with which such Places are but too much infested,” he also suggested that every thousand acres should be assigned a local bailiff, “whose business it should be continually to visit the Woods under his care, and to give an Account of what may occur to his notice.”[62] The plan offered a re-oriented natural hinterland and a welfare scheme all at once. It was a conservative wooden utopia, which would be monitored by the state and filled with docile laborers.

Replacing the fuel of London also meant the interruption of countless coal-fired systems that had already taken flight, and Nourse considered several of these in his final pages. What would happen to the northern coal owners and the miners they employed? He dismissed this problem with an appeal to the public good: coal sickened the miners and polluted the metropolis, providing profit for only a few.[63] He also conceded that coal was less “cumbersome” than wood—it was a more concentrated fuel that took up less space—and so he envisioned a network of ovens distributed throughout his forest, where the wooden harvest would be refined into a denser, purer charcoal.[64] The advantages of returning to wood, Nourse argued, would bring their own positive changes. It would reverse recent tendencies in land use that had incentivized landowners to “convert their barren Grounds into Wood-Plantations” instead of yielding to the temptation to “quit the Preservation” of forested land because of the availability of cheap coal.[65] Finally, Nourse addressed the tax on coal imports that was then funding the rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Implementing his “Project of Wood-fires,” he wrote, would take a long time; at least twenty-five years, according to his estimates. Through that delay, the coal tax could continue and St. Paul’s would be finished: “that admirable Fabrick may arrive to its Consummation.”[66]

Here again was Nourse’s attention to cascading consequences. Human decisions depended on material substrates, which then informed further questions that unfolded over time. Fuel was foundational in this regard. He showed how a coal-fired city precipitated a set of social, spatial, and material relations, while a wood-fueled metropolis would require different ones. If coal had initiated progressively faster cycles between fossil fuel use and its surrounding environment, a return to wood promised to reinstate slower and more manageable speeds. Nourse was, in effect, proposing a scheme of what we would now call de-carbonization, but his conservative utopia reveals what such schemes of material deceleration really involve. It is difficult to get rid of smoke without getting rid of fire, and getting rid of fire threatens to slow everything down. A city’s fuel was not just another commodity or raw material, but it served as a regulator for the whole social-natural system.

What finally emerged from these spiraling interactions between London, its fuel, and its social, material, and spatial management was something very different. Nourse revealed coal’s challenge to posterity. The preeminent English-language historian of early modern European wood use, Paul Warde, has argued that the problems raised by woodland management led to the consideration of unusually long horizons of time. Harvesting wood from a sapling took several years, and some tree species could take decades or even human lifetimes to reach maturity. “When you planted a tree you were planning ahead,” Warde summarizes. “The consequences of decisions taken in woodland management stretched far into the future.”[67] Forest management necessarily raised questions about what we would now call “sustainability,” which in turn led to issues of governance and regulation. Planning nature towards social and political ends meant creating institutional structures that could bridge between past yields, present demands, and anticipated needs; it required considering how to span between individual citizens, households, and larger scales of natural, social, and political organization. Many writers in England, Germany, and elsewhere attended to these intertwined concerns, and Nourse inherited their tradition. In his brief and incisive discussion of “An Essay on the Fuel of London,” Warde calls Nourse the “last of the wood projectors of the seventeenth century,” arguing that he occupied a “transitory moment” between the long tradition of projecting agricultural output and the then-emergent methods of political arithmetic and, later, political economy, with its new attention to the problems of demography, supply, and demand.[68]

Nourse’s text, however, was not simply an exercise in woodland planning; instead it imagined that a designed forest might counter the revolutionary pace unleashed by London’s coal. In this way, the essay suggests how we must run thought experiments in multiple directions. If the deliberate management of farm or woodland compelled a cyclical planning that corresponded to the repetition of annual growing seasons, “An Essay upon the Fuel of London” suggested, perhaps for the first time, that the time of coal would be different. It would proceed directionally, rather than cyclically; it would also proceed faster, creating and destroying with a new and unfamiliar intensity. Exchanging repeating seasons for subterranean forests of energy, fossil fuel would drive time deeper and deeper in one direction.[69]

Nourse concluded his text wistfully, admitting his “Project of wood-fires” was unlikely to be realized: “in truth all Great and Profitable Designs whatsoever are the Issues of Time, and Things of greatest Maturity and Duration are longest in their Concession.”[70] Fearing an accelerating future, Nourse imagined that his society could still gather itself to act with posterity in mind. His central contention throughout Campania Fœlix was that a judicious elite should be capable of designing its way out of collective problems in the disorderly city as much as on the managed estate. But as his meditation on material decay showed, fossil fuel had rendered designs on the future dangerously fragile. Coal use seemed, in a word, short-sighted. Restoring wood as the fuel of the city would recreate a metropolis in which things lasted as long as they should. Only an intentional redesign could slow or, better yet, reverse the inexorable momentum that coal had already set in motion.

In another sense, however, the project belonged to a previous era. By 1700, London had become entirely inconceivable without coal, and imagining the metropolis otherwise required the suspension of disbelief. Nourse, more than Evelyn, seemed to recognize this condition; he showed how coal had set off a chain reaction, reforming the expectations of the entire city it now fueled.[71] In time, the power, speed, and convenience of fossil fuels would prove difficult to refuse, despite their tortuous drawbacks. But at this early moment, Nourse glimpsed a material contradiction that seemed to inhere within this unruly source of energy. Through his plan and through his attention to the life of things in the polluted city, he intimated the affronts to time’s operation that would continue to unsettle all fossil-fueled societies.

Aleksandr Bierig is a Harper-Schmidt Fellow at the University of Chicago, IL

Acknowledgements: I would like to extend my gratitude to the editors and reviewers for their generous and detailed comments on this article. Thanks also to friends and colleagues for listening and responding to different versions of its arguments: organizers and fellow panelists as part of “Shifting Grounds: Visualizing, Materializing, and Embodying Environmental Change in the Early Modern European World (ca. 1400–1700)” at the College Art Association annual conference; Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Lucia Allais, and Jonathan Levy during a presentation at The Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University; and the thoughtful feedback of Robert Brennan, Jennifer Chuong, Igor Ekštajn, Brett Lazer, Caroline Murphy, Erika Naginski, Nicholas Robbins, and Jonah Rowen.

[1] Research on coal use by historians of ancient and medieval Britain is synthesized in John Hatcher, The History of the British Coal Industry. Vol. 1, Before 1700, towards the Age of Coal (Oxford: Clarendon, 1993), 5–30; 418–458. On coal’s long-distance supply chain, see Ray Bert Westerfield, Middlemen in English Business: Particularly between 1660 and 1760 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1915), 218–238. The problem of when, how, and why London switched to using coal was first put forward by historian John U. Nef, with what is known as his “timber crisis” thesis: John U. Nef, The Rise of the British Coal Industry, vol. 1 (London: Routledge, 1932), 158–164. Subsequent work has suggested that wood price increases were most likely limited to the London market. See Robert Allen, “Was there a timber crisis in early modern Europe?,” in S. Cavaciocchi, ed., Economia e energie secc. XIII–XVIII (Florence: Le Monnier, 2003), 469–477. For a complex, variegated view of the historical geography of fuel supply in England, see Paul Warde and Tom Williamson, “Fuel Supply and Agriculture in Post-Medieval England,” Agricultural History Review 62 (2014): 61–82.

[2] Derek Keene, “Material London in Time and Space,” in Lena Cowen Orlin, ed., Material London, ca. 1600, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 68.

[3] T. F. Reddaway, The Rebuilding of London after the Great Fire (London: Arnold, 1951), 73, 80–81, 126–128; Cavert, “Industrial Coal Consumption,” 11–12.

[4] This was perhaps the central theme of Wrigley’s distinguished career. On the relation between coal and urbanization, see E. A. Wrigley, “A Simple Model of London’s Importance in Changing English Society and Economy 1650-1750,” Past & Present 37 (1967): 44–70; E. A. Wrigley, “Urban Growth in Early Modern England: Food, Fuel and Transport,” Past & Present 225, no. 1 (November 1, 2014): 79–112. The best statement of Wrigley’s larger theses about the historical significance of the transition to fossil fuel remains E. A. Wrigley, Continuity, Chance and Change: The Character of the Industrial Revolution in England (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

[5] John Evelyn, Fumifugium, or, The Inconveniencie of the Aer and Smoak of London Dissipated Together with Some Remedies Humbly Proposed. (London, PUBLISHER? 1661), 5.

[6] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 5.

[7] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 7.

[8] William Cavert, “Urban Air Pollution and The Country and the City,” Global Environment 9, no. 1 (2016): 152–153. For Cavert’s exceptional study of pollution in early modern London, see William M. Cavert, The Smoke of London: Energy and Environment in the Early Modern City (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

[9] On early modern pollution, see Cavert, Smoke of London; Peter Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke: A History of Air Pollution in London since Medieval Times (London; New York: Methuen, 1987). On regulation and health, particularly in the nineteenth century, see Peter Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution: Coal, Smoke, and Culture in Britain since 1800, Ohio University Press Series in Ecology and History (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2006); Stephen Mosley, The Chimney of the World: A History of Smoke Pollution in Victorian and Edwardian Manchester (Cambridge, UK: White Horse Press, 2001); Eric Ashby and Mary Anderson, The Politics of Clean Air (Oxford: Clarendon Press ; New York, 1981). On smoke and literary culture, again in the nineteenth century, see Christine L. Corton, London Fog: The Biography (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2015); Jesse Oak Taylor, The Sky of Our Manufacture: The London Fog in British Fiction from Dickens to Woolf (Charlottesville; London: University of Virginia Press, 2016).

[10] On London and “early modernity,” see William M. Cavert, “London and England’s Early Modernity: A Review of Recent Scholarship,” History Compass 16, no. 8 (August 1, 2018): 1-10.

[11] Peter Brimblecombe and Carlota M. Grossi, “Millennium-Long Damage to Building Materials in London,” Science of The Total Environment 407, no. 4 (February 2009): 1354–1361.

[12] This emphasis on approaching the city and its planning as a material rather than spatial endeavor anticipated a larger tension in the nineteenth-century history of urban planning and its medical and chemical precedents. See Christopher Hamlin, “The City as a Chemical System? The Chemist as Urban Environmental Professional in France and Britain, 1780–1880,” Journal of Urban History 33, no. 5 (July 1, 2007): 702–728.

[13] To my knowledge, there are only a handful of extended discussions of Nourse’s essay: Rolf Peter Sieferle, The Subterranean Forest: Energy Systems and the Industrial Revolution, trans. Michael P. Osman (Cambridge: The White Horse Press, 2001 [1982]), 91–92; Cavert, The Smoke of London, 140–141; Paul Warde, The Invention of Sustainability: Nature and Destiny, c. 1500-1870 (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 98–101. These important books drew my attention to Nourse’s essay, though their analyses do not address the issues of material design, temporality, and the built environment that I explore in this piece.

[14] I am thinking here of William Sewell’s notion of “fateful temporality.” Historians, he writes, “see time as fateful, as irreversible in the sense that a significant action, once taken, or an event, once experienced, irrevocably alters the situation in which it occurs.” My argument here is not simply that the transition to coal in early modern London was fateful, though it was. Through Nourse, we can see how coal’s adoption altered temporality itself; coal seemed to accelerate the speed of time. W. H. Sewell, “The Temporalities of Capitalism,” Socio-Economic Review 6, no. 3 (April 15, 2008): 517–518.

[15] Scholarship on Fumifugium is considerable and includes Mark Jenner, “The Politics of London Air John Evelyn’s Fumifugium and the Restoration,” The Historical Journal 38, no. 3 (1995): 535–551; Peter Denton, “‘Puffs of Smoke, Puffs of Praise’: Reconsidering John Evelyn’s ‘Fumifugium’ (1661),” Canadian Journal of History/Annales Canadiennes d’Histoire 35, no. 3 (December 1, 2000): 441–451; Toby Travis, “‘Belching It Forth Their Sooty Jaws’: John Evelyn’s Vision of a ‘Volcanic’ City,” The London Journal 39, no. 1 (March 1, 2014): 1–20; Cavert, The Smoke of London, 173–194.

[16] Jenner, “The Politics of London Air,” 541.

[17] Evelyn, Fumifugium, unpaginated, dedication.

[18] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 6.

[19] William Cavert, “Industrial Coal Consumption in Early Modern London,” Urban History (April 8, 2016): 1–20.

[20] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 17. For an overview of the spatial history of the Port of London, see L. Rodwell Jones, The Geography of London River (London: The Dial Press, 1932).

[21] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 24.

[22] Cavert, The Smoke of London, 180.

[23] Evelyn also mentioned this national difference, writing, “I have, I confesse, been frequently displeased at the small advance and improvement of Publick Works in this Nation, wherein it seems to be much inferiour to the Countries and Kingdomes which are round about it.” Evelyn, Fumifugium, unpaginated, dedication.

[24] John Evelyn, A Character of England as It Was Lately Presented in a Letter to a Noble Man of France (London, 1659), 29–30. This passage from his earlier essay continued on to predict the litany of complaints from Fumifugium: “if there be a resemblance of Hell upon Earth, it is this Vulcano in a foggy day: this pestilent Smoak, which corrodes the very yron, and spoils all the moveables, leaving a soot upon all things that it lights: & so fatally seizing on the Lungs of the Inhabitants, that the Cough and the Consumption spare no man.”

[25] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 15. The supply of wood to Paris in this period involved different woodland sources supplying the city’s fuel through a spectacularly complex system of floating wood down waterways that eventually led to the Seine. See Annik Pardailhé-Galabrun, The Birth of Intimacy: Privacy and Domestic Life in Early Modern Paris, trans. Jocelyn Phelps (Cambridge: Polity, 1991), 123–125.

[26] G. E. Fussell, “Campania Foelix, 1700. A Curiosity of Farming Literature,” Notes and Queries 176, no. 14 (April 8, 1939): 237–239.

[27] “Nourse, Timothy (c. 1636–1699), Agricultural and Religious Writer | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.”

[28] For background on the social structure of rural England around this time, see J. M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in Common-Field England, 1700-1820, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

[29] Walter Blith exemplified the “professionalism” and the willingness to revise his recommendations based on empirical experience, writes agrarian historian Joan Thirsk. Joan Thirsk, “Agricultural Innovations and their Diffusion,” in Thirsk, ed., The Agrarian History of England and Wales: Volume 5, 1640-1750, Part 2, Agrarian Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 546–548.

[30] This paragraph concludes: “this kind of Employment may most properly be call’d a Recreation, not only from the Refreshment it gives to the mind, which may be lookt upon as a New Creation of things; when from Nothing, or from something next to Nothing, we become the Instruments of producing, or of restoring them in such Perfection.” Timothy Nourse, Campania Fœlix.: Or, a Discourse of the Benefits and Improvements of Husbandry … (London, 1700), 2.

[31] The conflation of natural and social “improvement”—often through entreaties to divine authority—is an important theme in its intellectual history. For a sanguine view, see Paul Slack, The Invention of Improvement: Information and Material Progress in Seventeenth-Century England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). For a wary view, see Richard Drayton, Nature’s Government: Science, Imperial Britain, and the “Improvement” of the World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000); and for a dispassionate view, see Paul Warde, “The Idea of Improvement, c. 1520–1700,” in Custom, Improvement and the Landscape in Early Modern Britain, ed. Richard W. Hoyle (Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011).

[32] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 59. This was understood to be a common problem. Agrarian historian Christopher Clay notes that “cottagers also tended to cause damage when they illicitly helped themselves to fuel.” Christopher Clay, “Landlords and Estate Management in England,” in Thirsk, ed., The Agrarian History of England and Wales, 237.

[33] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 103–105.

[34] This was evident, he argued, in Scotland, Sweden, and Switzerland: “as they are the poorest Countries, so do they yield the bravest Soldiers in the World.” Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 100. This tension is summarized in Neeson, Commoners, 20. See also the discussion of Nourse’s attitude toward commoners in Vittoria Di Palma, Wasteland: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 58.

[35] William Alexander McClung, “The Country-House Arcadia,” Studies in the History of Art 25 (1989): 279.

[36] James Ackerman, “The Villa as Paradigm,” Perspecta 22 (1986): 10–31.

[37] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 297.

[38] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 303–338. Stairs and rails at 308–309; upper floor windows at 304; gardens at 316–326; the little village at 331.

[39] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 331; Katherine Myers, “Ways of Seeing: Joseph Addison, Enchantment and the Early Landscape Garden,” Garden History 41, no. 1 (2013): 14.

[40] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 340; Ecclesiastes 2:4–15. Pheme Perkins et al., eds., The New Oxford Annotated Bible with Apocrypha: New Revised Standard Version, fourth edition (Oxford U.K.; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 938.

[41] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 342–344.

[42] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 349.

[43] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 6.

[44] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 350–352.

[45] Elaine Tierney, “‘Dirty Rotten Sheds’: Exploring the Ephemeral City in Early Modern London,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 50, no. 2 (2017): 235–238.

[46] While the word-concept of “feedback” dates from the twentieth century, historian of technology and science Otto Mayr outlined its early modern origins. See Otto Mayr, “The Origins of Feedback Control,” Scientific American 223, no. 4 (1970): 110–119; Mayr, Authority, Liberty, and Automatic Machinery in Early Modern Europe (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986).

[47] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 352.

[48] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 352.

[49] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 357–358. A “chaldron” of coal was a measure of volume, now obsolete, which varied by region. See Sidney Pollard, “Capitalism and Rationality: A Study of Measurements in British Coal Mining, ca. 1750–1850,” Explorations in Economic History 20, no. 1 (January 1, 1983): 110–129.

[50] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 361.

[51] James Campbell, Building St Paul’s (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007), 64–68.

[52] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 350–352. Cavert identifies an earlier, remarkable episode from the 1620s and 1630s when the earlier, pre-fire iteration of St. Paul’s Cathedral was the subject of a campaign to restore the building from its decayed state, which some blamed on the city’s coal smoke. Cavert, The Smoke of London, 49–53.

[53] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 364.

[54] I am thinking here of Joseph Schumpeter’s well-known characterization of capitalism as advancing through the “process of creative destruction.” Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (New York: Harper, 1943), 81–86.

[55] Timothy Hyde, “‘London Particular’: The City, Its Atmosphere and the Visibility of Its Objects,” The Journal of Architecture 21, no. 8 (November 16, 2016): 1274–1298; Edward John Gillin, “Stones of Science: Charles Harriot Smith and the Importance of Geology in Architecture, 1834–64,” Architectural History 59 (2016): 281–310; Jorge Otero-Pailos, “The Ambivalence of Smoke: Pollution and Modern Architectural Historiography,” Grey Room (July 1, 2011): 90–113.

[56] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 354 (2). The digital version of the first edition of Nourse’s book that I consulted through the Gale Database “Making of the Modern World” collection contains repeat pagination towards the conclusion of the book. The page numbers I mark with “(2)” indicate the reference can be found on the second instance of this page number.

[57] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 349.

[58] This aspect of Nourse’s text is emphasized in the existing secondary literature on Nourse. See above, note 13.

[59] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 352.

[60] The immense space needed to grow enough firewood to equal the power of coal anticipates the calculation of the “ghost acre”—the ways in which certain societies arrogate to themselves resources that exceed the natural capacities of their arable land. Ghost acres are defined either as 1) the absent, colonized agricultural land whose produce benefits the metropole; or 2) the fictitious woodland that would be required to produce the same amount of heat energy as those provided by fossil fuels. The most well-known use of this concept is Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 275–277, 313–315. For a fuller genealogy of its use, see T. L. Whited, “Nature and Power through Multiple Lenses,” Social Science History 37, no. 3 (1 September 2013): 347–359; Libby Robin, Sverker Sörlin, and Paul Warde, eds., The Future of Nature: Documents of Global Change (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 40–53. On the significance of the ghost acre concept, see Fredrik Albritton Jonsson, “The Industrial Revolution in the Anthropocene,” The Journal of Modern History 84, no. 3 (2012): 692–694; Aleksandr Bierig, “Building on Ghost Acres: The London Coal Exchange, circa 1849,” in Environmental Histories of Architecture, ed. Kim Förster (Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architetcure, 2022), 1–3.

[61] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 355.

[62] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 353–354.

[63] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 359–360.

[64] While he acknowledged that this network of fuel-processing ovens would cause its own pollution, he claimed it would be “incomparably less than the continual stink of the Sea-Coal Fires.” Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 362. The immense space needed to grow enough firewood to equal the power of coal also exemplifies Vaclav Smil’s much more recent concepts of “energy density” and “power density”: the amount of heat (energy) or work (power) that can be produced from a given quantity of fuel or land area of energy production. See Vaclav Smil, Energy in Nature and Society: General Energetics of Complex Systems (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007), 18–20.

[65] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 360.

[66] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 353 (2).

[67] Warde, Invention of Sustainability, 59; 90–101.

[68] Warde, Invention of Sustainability, 100. In his pages on Nourse, Warde warns that “We should not slip into labelling such men as prescient before their time,” drawing particular attention to the lack of empirical techniques regarding Nourse (and Evelyn’s) approach to the problem of pollution’s effects on human health. I hope to have shown here that, beyond the detailed questions of Nourse’s relation to the history of medical theory and statistical quantification, a close reading of his text suggests that other, less discussed, themes of temporality and durability—particularly as they became manifest in the built environment—lend his essay significance for the history of thinking about and with fossil fuels.

[69] A century and a half later, William Stanley Jevons put forward a similar idea about coal’s relation to temporality in The Coal Question (London, 1865), particularly in its concluding chapter.

[70] Nourse, Campania Fœlix, 353–354 (2).

[71] The catalytic, enabling quality of coal makes it, among other things, an entity that economists refer to as an “intermediate good”—a thing consumed in the process of making or moving other things. On the historical and conceptual problems of this category, see Emma Rothschild, “Where Is Capital?,” Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics 2, no. 2 (2021): 291–371. Coal is discussed at 320.

Cite this article as: Aleksandr Bierig, “Restorations: Coal, Smoke, and Time in London, circa 1700,” Journal18, Issue 15 Cities (Spring 2023), https://www.journal18.org/6757.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.