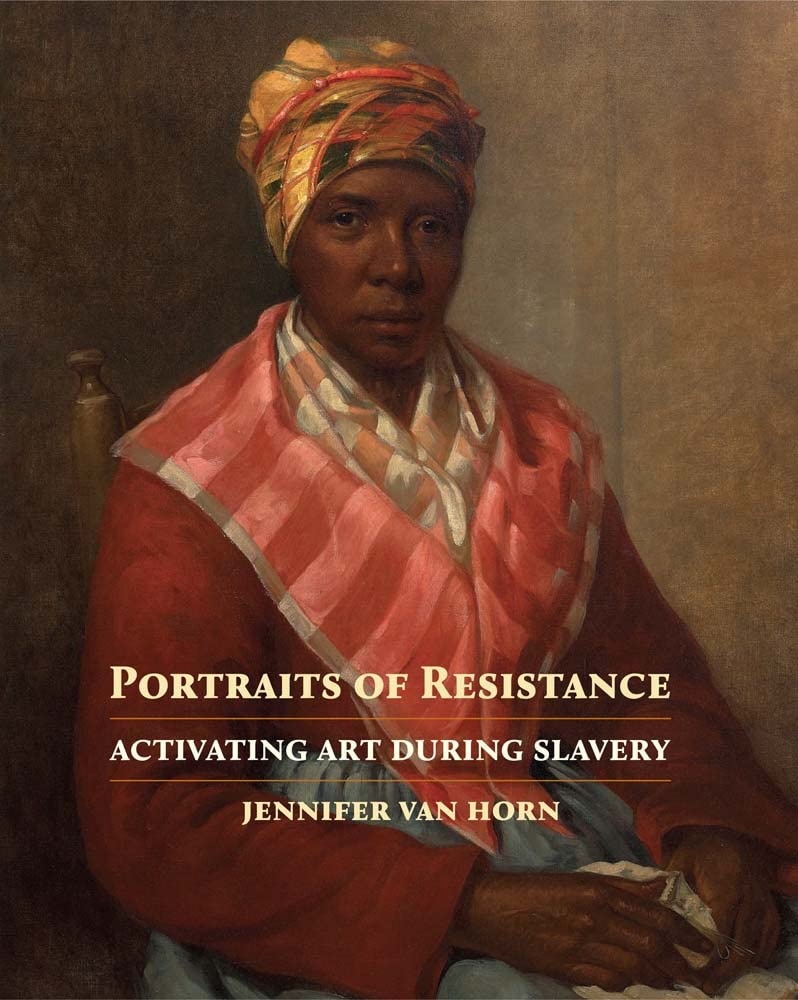

The cover to Jennifer Van Horn’s Portraits of Resistance: Activating Art under Slavery (Yale University Press 2022) features a striking portrait of an aging Black woman, shoulders draped in shining stripes and head wrapped in a madras tignon (Fig. 1). While it is virtually impossible not to be captivated by the frank gaze of Delia, the subject of this 1840-49 portrait by James Reid Lambdin, the multi-layered history unveiled inside the book’s covers brings new dimension to an already exceptional image. Encountered in the course of Van Horn’s field research in private and public collections throughout the American South, Delia’s portrait is just one of several oil on canvas depictions of enslaved sitters that appear in this eloquently written and richly illustrated volume. Intimate and humanizing, these portraits were nonetheless commissioned by the subjects’ enslavers as yet another means to exert bodily control. Van Horn unpacks the exploitative conditions of these portraits’ production while also attending to the possibilities such images may have provided the sitters as a means to assert personal identity and to materialize one’s intrinsic “soul value.” Both unsettling and profoundly moving, Van Horn’s reading provocatively troubles conventional understandings of portraiture’s role in the construction of the autonomous subject.

Of course, such portraits are only part of the story. Over the course of the book, Van Horn charts a chronological account of portraiture’s imbrication with slavery from the seventeenth through early twentieth centuries, while simultaneously tracing the lifecycle of the portrait as a medium from creation to reception and ultimately destruction. This analysis incorporates accounts of enslaved people’s own artistic labors, from house painting to oil painting, alongside extended exploration of the conditions governing African American viewership and the creative repurposing of white portraiture by the formerly enslaved in the aftermath of the Civil War. Setting out to demonstrate “that enslaved African Americans were a piece of every part of portraiture,” Van Horn probes these images, objects, and creative practices as both the product of slavery’s inhumanity and a form of resistance within it. The resulting book centers the portrait as a key player not only in the development of a distinctly American art, but also in the far more consequential battle over personhood in American society.

Van Horn and I recently sat down to discuss the project:

Elizabeth Eager: I’d like to start by talking about the origins of Portraits of Resistance. Toward the end of the book, you mention that research for the project began in 2013. But your first book, The Power of Objects in Eighteenth-Century British America, was published in 2017. Given the overlap, I wonder if you could talk about how these two projects might be related and whether there’s a larger trajectory you see in your work.

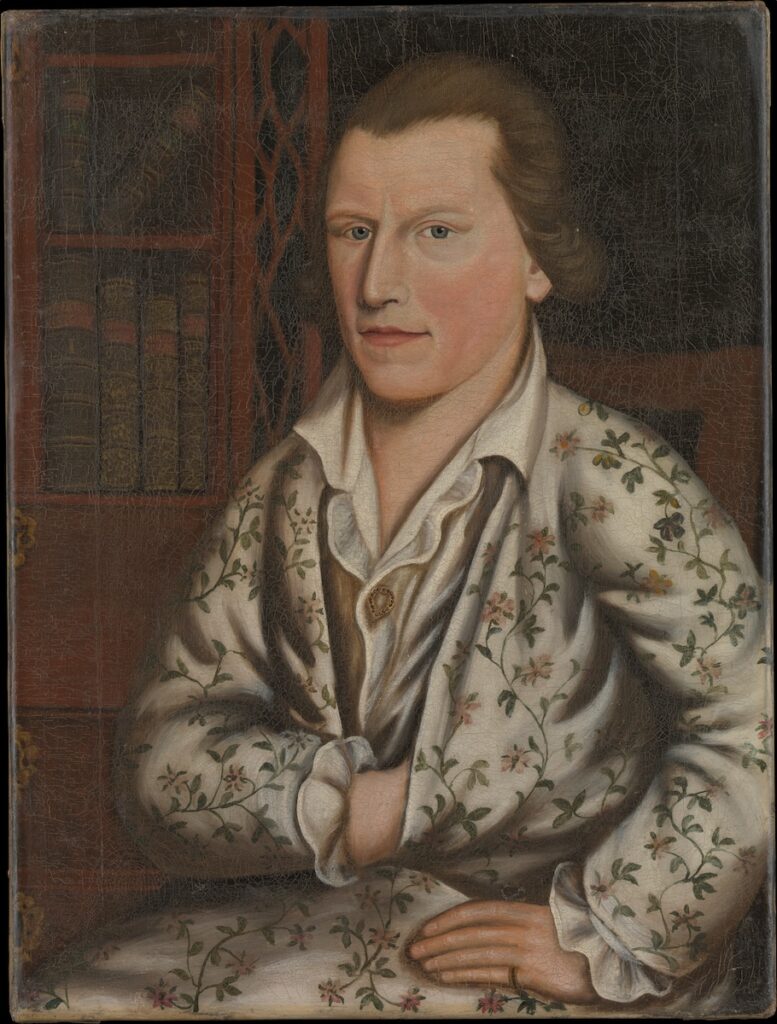

Jennifer Van Horn: In The Power of Objects, I was looking at British portrait painter, John Wollaston. As part of that research, I was going to many, many museums and looking at their Wollaston paintings, including this portrait [from the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA)] of South Carolinian Daniel Ward (Fig. 2). MESDA had an important collecting campaign in the twentieth century, where they would go around to various private collections in the South, catalog what was there, and take photographs. They compiled this massive database of material and family history. The history that came in with the Daniel Ward painting was from white descendants of the McGillivray family, who recalled that during the Civil War someone formerly enslaved by the family had seized this painting, taken it to their dwelling place, and turned it into a fire screen. After the war ended, a white family member retrieved the painting.

That was the start of the Portraits project. It was just this very tantalizing story about an object’s life history in this file. I was totally intrigued and put it in my file of “This is amazing. And I want to know way more about it.”

I think the first project was also significant in the development of Portraits, because part of it touched on the South. I realized how much there was yet to do in terms of Southern, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art history, and how much of that history was related to Charleston, partly because it was this incredible incubator of taste and fashion and style, but also because of the city’s involvement with the slave trade and as a site of enslavement.

A lot of the thinking that was required for the second project—being creative about evidence and following object stories after the moment of creation—I think those kinds of methodologies are baked into material culture studies in a way that lend themselves well to thinking about understudied art histories of enslaved people of African origin and descent. So, while their topics are really different, the books share a lot of the same strategies.

EE: On that note, your first chapter deals not only with the work of the enslaved portraitist Prince Demah but also with all of the forms of enslaved labor that might have gone into the production of portraiture in the eighteenth century (Fig. 3). It was this wonderful reminder that we are interested in questions of materiality, process, and labor not just because they are intrinsically interesting, but because they reveal stories that don’t get told if you simply stop at the surface of a painting.

JVH: You know, if we are looking at understudied peoples, material things can provide a way to start to investigate those histories, and I think that’s been a mantra of material culture studies since the seventies. But absolutely, I take your point that the emphasis on making and creation can be framed as apolitical. For me it came down to how and why we decide that “making” has ended. If it’s only artists when they put paint on canvas who make things, that is just such a circumscribed view. We don’t then see the full range of labor and actors involved in the object’s story. This long life-history helps to complicate those ideas about whose labor counts.

EE: Maybe that takes us back to the question of research process and the way the story of the Daniel Ward portrait is told solely through the words and memory of the McGillivray family. I wondered if you could maybe talk about your research process and how you went about identifying other objects that might fit this same narrative. How did you move outward from the Daniel Ward portrait to the other examples that populate the book?

JVH: Basically, every person who engaged with the project said, “Well, that’s really interesting. Are you going to have any evidence? I can’t believe you’re finding any evidence.” And it became a question for me, “Well, is there some quantitative amount? If I find twenty examples, is that enough?” I mean, how would you know?

That response led me to a couple of things. One, historians of slavery, and in particular Black feminist scholars, have modeled so many ways in which to engage with the tainted and incomplete archives that survive, and I’m absolutely indebted to their work. That was vital. Two, instead of running away from absence, I decided that I was going to talk more about structural inequality and the reasons that the kinds of evidence people feel they need to have just wasn’t findable in the numbers that they wanted. I also wanted to think about absence being something that points to larger issues of power and dynamics of repression, and then to look for creative ways to assert agency that wasn’t documentable. That too is very much based on the work of Black feminist scholars who have called attention to the fact that absence isn’t a stopping point. Absence is a way to begin to critically interrogate the past. What can we know with what is left, and how do we leave space for what we hope might be?

EE: So then how do you know when to stop looking? I mean, how do you ultimately define the condition of absence?

JVH: I was thinking about this question in relation to Prince Demah. We know, because of the writings of his enslavers and from his mother’s words transcribed in a letter, that he’s creating pastel portraits and that they survive at least past the American Revolution. So potentially somewhere, they’re out there. So when it came to his self-portrait, I searched. And if there had been one that I felt, “Oh yeah, that is totally it,” I would have included it, but there wasn’t.

I decided what was important was to think about what his self-portrait might have looked like had it survived, based on what was around in the period and the way artists conceived of self-portraits at the time, and that does have real implications. Maybe now somebody will find a self-portrait by Demah, because they’ll be looking for it as an image that frames him as an artist instead of just portraying him as a seated Black figure. So maybe that actually helps to fill that absence.

In the case of Homer Ryan [which deals with a portrait of an enslaved man discussed in archival records but never found], that one was a little bit different. There I did decide to stop. In this case, stopping was an opportunity to think through the ways that portraits of people who were enslaved may have been made against their will or without their full approval, and to reflect on the status those images occupy in the present. Whose histories are they? Whom do they belong to? How do we begin to redress historic injustice with these images? Those are questions that have been swirling around photography, in particular, but I think they are equally applicable to paintings. For me, absence can be a way to think through what justice looks like.

EE: Picking up on your discussion of Homer Ryan, I wondered if there was an object or story that got away? It sounds like the Ryan portrait is in some ways that object but also not. So is there another object that you wish you could have found, or are there other lingering traces you want to follow up on?

JVH: I think the piece that I’ve been most excited to see continue is one that was loosely in the book, a painting we now know as Bélizaire and the Frey Children (Fig. 4). At some point in the painting’s history, the African American child in the background was covered up, probably by members of the Frey family. Sold from a museum collection, the painting was acquired by the private collector Jeremy Simien, who had conservation work done that fully revealed the African American figure. Along with a historian colleague, he also recovered the history and identity of this figure, Bélizaire, as well as the history of the white Frey family members. The painting is now at the Met where it’s been a huge star, and Jeremy has gotten the chance to share his story and its story widely, which I think is wonderful. It has a thoughtful response label written by Mia Bagneris, and it also has a label with the pre-conservation image, so you can see the kind of life history of that object. It’s thrilling that it’s at the Met and it’s getting this attention.

But one of the other things I think a lot about in this project is how place matters for thinking about slavery. I was lucky enough to get research funds that allowed me to spend two summers going through various parts of the South—Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama—getting a chance to go to historic house museums and art museums that I had never been to before and looking for these paintings, some of which ultimately came into the book. So, it’s startling for me to have that painting of Bélizaire and the Frey Children, which is so deeply enmeshed in Louisiana history, instead installed at the Met, which is this global museum and tells a national and global story. I’m happy that it’s there, but at the same time I worry about the fact that it is out of its home context of Louisiana and also that it might too easily lead folks to once again assume that slavery is a Southern phenomenon only. I worry that this is a missed opportunity to ground institutional history within that larger history of unfreedom in New York. On one hand, it is a wonderful thing to see this painting enter the public square, but at the same time, I hope it opens up more conversation around slavery in New York itself.

EE: I noticed throughout the book, but particularly in the latter chapters, that you sought to draw out the role of women in the long lifecycle of portraiture. I got the feeling that you were trying to highlight the absence of women in the textual archive of slavery, but this wasn’t overtly acknowledged in the framing of the book. Can you talk more about the gendered dynamics of this history and the sources you’ve mobilized?

JVH: Absolutely! I got about halfway through and realized I have a book full of Black men. I was glad to have found these stories, but also, what about women? How are Black women left out of the archives in relation to enslavement? I think when I found Daphne Williams’s Federal Writers’ Project interview talking about her experience of viewership as an enslaved child, that was just such an important moment.[1] It did shape the second half of the book, because it allowed me to understand how to bring Black women’s experiences, and their acts of creative resistance, into the narrative that I was building in ways that focusing on making alone hadn’t done up to that point.

EE: I also wonder if we could talk about how you use evidence like this Daphne Williams interview. You build out these remarkable interpretations of a single object or text, any one of which another scholar would be happy with as the central argument of a chapter, and then you bring us back to the start to look at the same subject from a slightly different angle. Would you mind talking about that writing process and why you pursued this kind of recursive form of argument?

JVH: This is a roundabout way of answering that question, but early on, I was presenting some of the materials from chapter two, which is about the Washington Family group portrait that includes a figure who may be Christopher Sheels (Fig. 5). Some very kindly, smart, wonderful curators heard me give a talk about this painting and came up afterwards and said, “Okay, so do you feel we should change the identification of that figure on our label then?” There was this need to have a definitive, positive, empirical statement, when what I had been trying to say was that I think this might be Christopher Sheels, these are the ways in which that could be possible, and this is why we may not know, or why we may never know.

So, as far as the recursive structure of the book’s arguments, I wanted to frame these arguments in ways that allowed the reader to see how I’m transparently putting evidence together, where I have to guess, where I can’t know, where I’m making an assumption, and why I’m making it. Partly this is about the recursive nature of the evidence itself, which is so often these misdirections, or omissions, or passing references. But it’s also about a cumulative destabilization rather than making that definitive, positive statement. If there is a positive statement, it is that Black people are fundamental for the creation of portraiture in the early United States. Right? That’s it. At the same time, the nuance of exactly how, exactly where, exactly when—all of that is where things get complex.

EE: Portraits of Resistance addresses not only the central tenets of American portraiture—subjectivity, likeness, refinement, consumer culture—but also the entire canon of American art. Even as it foregrounds Black actors, its pages are filled with the work of Smibert, Copley, West, Peale, Stuart, Savage, Sully. It really is a work that retells this history of American art from within the system of slavery. This leads me to ask how your work on this book has reshaped your own teaching, as well as how you hope it might reshape our field’s approach to the teaching of American art in general.

JVH: You know, I’m very much indebted to those who teach African American art history, and I think my own teaching is an attempt to bring African American art history and the teaching of American art together in ways that celebrate the accomplishments of both while also showing these moments of deep hostility. In the book, I tried to strike a balance. On one hand there’s remembrance and recovery, in so much as it was possible, of these important histories of individuals who had not been given their full due. On the other, there’s the work to problematize whiteness. It was important to me that whiteness not be the whole story, because I think that it can sometimes be an excuse to continue looking at the same works we’ve always looked at. It’s important to note that these artworks were instrumental for the construction of white supremacy, but that’s not enough. I think we need to change narratives and change what we include as opposed to just being more critical about the art that we’ve always looked at.

EE: On that subject, I think there’s one big thing that we have not talked about. You are very forthright in the book’s introduction about the missing pieces in the story you’re trying to tell, and we have talked a lot about how you’ve sought to fill in these absences. But you also acknowledge some trepidation in speculating as to the inner thoughts, feelings, motivations of the enslaved subjects whose stories you’re trying to recover. So, I wonder if you could talk about how you’ve sought to navigate your own subject position in this project?

JVH: Of course. Right now, I think we’re seeing the power of critical fabulation as a way to think about absence and to tell the stories of those who have not traditionally been allowed into the history of American art. In the next five years, I think we’ll see a tremendous number of works using critical fabulation across the humanities and social sciences, which will allow us to actually understand what we mean by this method and how to do this work as ethically as possible. Someone like Marisa Fuentes, another powerful advocate for reading histories against the grain, has voiced ideas around being careful with critical fabulation, reminding us of the importance of respecting privacy, and not narrating violence and thereby perpetuating harm. For me, her words brought to mind the question of limits. I tried to be very transparent in the book about when my own voice came in versus when I was thinking through the actions of historical people. I was not out to recover, nor should I have access to individual subjectivity. As a researcher, I wanted to find as many pieces as possible. But, as an author, I tried to be careful about not inserting myself into that space.

There’s also this other piece we have to think about going forward. Sometimes when people ask this question about subjectivity, what they mean is, are you allowed to do that? Is that work that you’re allowed to do as a white scholar? And honestly, this is a question we can continue to think about as a field. For me, it was important to recognize the inherent racism that has structured the field of American art (and art history more generally) and to start to redress those absences right away. This is not to say we shouldn’t also be working toward a much more inclusive field. We should! I think that until art history has many more voices in its ranks, we will continue to face racism. My feeling is that in a white-centric field, we created this problem, and it is now incumbent upon all of us to help redress that.

Elizabeth Eager is Assistant Professor of Art History at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, TX

Jennifer Van Horn is Associate Professor of Art History and History at the University of Delaware and President of the Historians of Eighteenth-Century Art and Architecture

[1] Daphne Williams’s interview is part of the Federal Writers’ Project Slave Narrative Collection Library of Congress and can be found here: https://www.loc.gov/resource/mesn.164/?sp=166 and photographs taken of her here: https://www.loc.gov/item/mesnp164160/ (accessed 3 May 2024).

Cite this note as: Elizabeth Bacon Eager, “Portraits of Resistance: An Interview with Jennifer Van Horn,” Journal18 (May 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7348.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.