Editor’s note: This essay by Damiët Schneeweisz is a pendant to David Pullins’s Contained Assertions: Marie Victoire Lemoine’s Paint Box. Together, Pullins and Schneeweisz unpack two paint boxes that belonged to Marie Victoire Lemoine (1754-1820) and Charlotte Daniel Martner (1781-1839), bringing out how these boxes tie the material history of painting to gender, colonialism, and enslavement.

In Charlotte Daniel Martner’s self-portrait miniature (1805), the classical tendencies of French eighteenth-century portraiture collide with a distinctive burgeoning Antillean visual culture of the early nineteenth century (Fig. 1).[1] The miniature is a contrast in colors: the artist’s luminous pale white skin and Empire dress, emanating from the portrait’s ivory ground like moonlight, set against the darker skin tones of the man, women, and child that surround her, each dressed in dulled shades of red, orange, blue, and beige. The precise status of the four Black individuals within this household is unclear, and they are yet to be identified, but their placement, each suspended in an act of domestic labor, suggests that perhaps they depict those then enslaved in Martner’s home. At the center of the portrait is a brisk loss, as if someone has pressed their thumb to the watercolor and swept away Martner’s features, leaving only a set of auburn eyes, the contours of a nose, dark-brown eyebrows, and loose curls pinned back with a bejeweled comb.

That it is precisely Martner’s facial features—where the skill of someone trained as a portrait miniaturist was most on display—that are lost here is poignant. After all, this is a self-portrait of the artist next to her paint box, akin to those exhibited by Adelaide Labille-Guiard and her students at the French Salon, where Martner may have seen them as a girl prior to relocating from Paris via Louisiana to the Caribbean with her husband in 1803.[2] Emulating these earlier portraits in pose as well as finery, Martner painted her arm resting casually on the mahogany paint box’s green baize surface next to a small ivory palette, and her hands balancing a finished miniature portrait and lilac flowers. These features would be unremarkable were it not that this miniature was made in Martinique, once known by its Indigenous Taíno name Madinina, or “island of flowers.”[3]

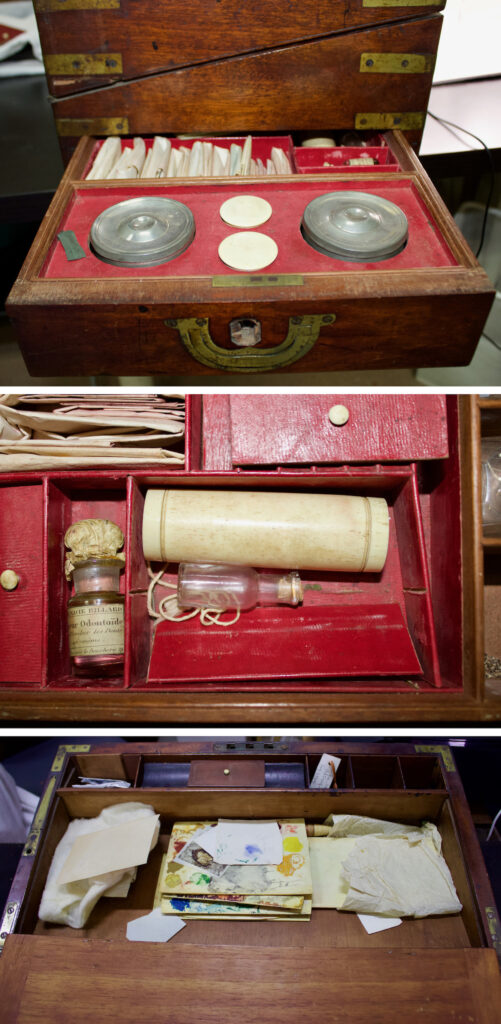

Perhaps even more striking than the existence of the self-portrait miniature is the fact that it has remained, intact, inside the very paint box it depicts (Figs. 2 and 3). There it has been stored alongside other miniatures, tools, palettes, pigments, and notes that date to Martner’s period of residence in Martinique, from 1803 to 1821.[4] Discrete and mobile, portable paint boxes like this enabled more women to work as miniaturists and propelled them to travel.[5] Martner likely had her paint box shipped from France, although, at least in materials, the journey simultaneously marked a return—the box’s fashionable mahogany timber was almost certainly sourced in the Caribbean by enslaved laborers.[6]

In what follows, I consider the importance of Martner’s paint box as a material archive of a woman miniaturist in the Caribbean during the era of the transatlantic slave trade. Mirroring the visual composition of the self-portrait, in which the artist has situated herself in the midst of a distinctly Antillean scene alongside four Black and potentially enslaved individuals, I ask what it meant for a white French woman miniaturist to work within a racially stratified plantation society, and what the implications are of thinking through Martner’s paint box, and artistic practice in the Caribbean more widely, as entangled in the plantation economies that characterized the colonial Caribbean.[7]

The box itself is skillfully crafted and similar to other table desks made in Europe. A diagonal slit along the sides reveals its primary function, once opened, as a portable desk. Drawers open to smaller compartments crafted to hold the tools for drawing, writing, and miniature painting (see Fig. 3). The surface of the desk is covered in green baize, underneath which are two more storage areas, filled with palettes, ivory sheets, unfinished miniature portraits, and rows of neatly packed and labeled pigments. Evidence that the box was once frequently used abounds, including spilled pigment, chipped corners, and ink stains caught on the surface that match the precise location of a quill and ink jar on the desk in the self-portrait.

While the extent to which the box today corresponds to Martner’s period of residence in Martinique is unclear, the contents include several things she created in the colony, such as portrait miniatures and sketches, and a poem gifted to the artist praising her portrait of Madame de la Pagerie (Empress Josephine’s mother and a plantation owner in Trois-Îlets). Archival records further reveal that Martner purchased materials, including canvas and frames, in Fort de France.[8] That knowledge is important, for it shows both Martner’s economic involvement and her dependence on the craftsmanship of enslaved people who worked as smiths, carpenters, painters, pickers, weavers, and in other forms of skilled labor.[9] In fact, enslaved people lived in Martner’s household throughout her time in Martinique. In 1818, she sold several people as part of her deceased husband’s estate: Isidor (age unknown), Paul (15), Marie (17) and her son Léandre (2), and Marie Louise (42) and her son Charles (7).[10] It is possible that she may have relied on their labor for physically strenuous and time-consuming work, such as the processing of pigments or preparation of grounds and supports for painting.[11] Martner featured Black individuals in intimate domestic surroundings in her works too, some of which she even kept and stored in her paint box alongside miniatures of her own kin (Figs. 4 and 5). These connections certainly suggest a close personal relationship that begs further study, including the compelling possibility that we might identify individual sitters.

To think through the contents of Martner’s paint box—palettes, burnishers, brushes, ivory sheets, pigments, and miniatures—highlights how the painting process was entangled with enslaved labor, from the sourcing of materials to the artist’s techniques. It also redirects our attention as art historians to the politics of miniature production in Martinique. The move from Europe to the Caribbean was accompanied not only by a shift in technique—miniaturists had to adapt their materials to the region’s heat and humidity, and repeatedly sought to reassure their clientele that their works were as lifelike as they were durable—but also by a change in value.[12] The paint box’s survival testifies both to Martner’s singular skill and the professionalization of her craft, and to the complicated status of women’s productivity and value in the Caribbean during the era of the transatlantic slave trade. One particularly striking advertisement, and the earliest archival record of Martner’s residence, details the self-liberation of Maximin, an enslaved cook, from Martner’s home:

Departed: the maroon negro Maximin, cook, 25 years old, black skin, handsome & well built. He formerly belonged to Mr. Manière of Saint-Pierre. That which will lead him to the first prison or to his master, Mr. Martner, in Fort de France, will be well rewarded.[13]

Just a few months later, another published newspaper notice praises Martner herself for her bust at a celebration in honor of Empress Josephine’s mother, who owned a sugar plantation in Trois-Îlets:

This well-made bust is by Madame Martner, who paints the miniature and the portrait with much success. She resides in Fort-de-France.[14]

Both newspaper fragments employ the French term bien fait to denote value—whether that of a human being, objectified to his productive potential, or a portrait bust. The echo of a single phrase—well made—encapsulates here the ways in which artistic practice, plantation economy, and enslaved labor entwined in a mutually dependent system of vision and value.[15] It is this economic nexus that also underlies Martner’s paint box and its appearance on the self-portrait, and that sustains parallels with the production and circulation of portrait miniatures in the Caribbean more generally, in which (women’s) reproduction, commodification, and kinship was central.[16]

Ultimately, the striking inclusion of the paint box within Martner’s self-portrait of 1805 already gestured to the complexity of these relations and her artistic practice as it would develop over the following decade. By the turn of the nineteenth century, Martinique’s success as a plantation society depended on women’s reproductive labor to maintain and grow the colony’s enslaved and free population—a context present in the self-portrait in the form of a woman nursing a small child.[17] For Martner herself, however, it appears to be the art of making portrait miniatures that stands in for her procreative ability in the colony, placing the portrait’s indebtedness to French women’s portraiture with which I began this note in an entirely new light. Amid abundant musical, artistic, and natural references, the paint box not only affirms Martner’s virtuous womanhood, but also puts forward an argument for her own economic industriousness in aid of the colonial project: on display are the various ways in which Martner has already created—as an artist and as the manager of a multiracial household—alluding to her reproductive capacities in the colony.[18]

Such references ultimately complicate the portrait’s representation of artistic agency, reframing Martner’s ability to create as part of women’s broad ability to reproduce, and the potential fruits of that work. Abstracted on a larger scale, the portrait’s strategic mediation of women’s artistic agency with traditional feminine virtue might signal a more complex understanding of the miniature’s place in colonial societies, too—in the end, both relied on the collapsing of people and kinship relations into commodities with the potential for future gain. To art historians, Martner’s paint box might serve as a cipher for both her own biography and that of artistic production in the Caribbean more widely.

Damiët Schneeweisz is a PhD Candidate at The Courtauld Institute of Art currently on Doctoral Placement at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London

This note was developed in collaboration with David Pullins, whose note on Marie Victoire Lemoine’s paint box I encourage you to read in tandem with this text. I owe my thanks to him, as well as Meredith Martin, Hannah Williams, and Catherine Girard, who orchestrated this pairing, for their support and insightful feedback. My gratitude further goes out to my doctoral supervisor, Esther Chadwick, for reviewing a draft of this note.

[1] I refer to the artist by both her maiden name Daniel and her married name, which corresponds to her signature and monogram at the time of arrival in Martinique. Her signature changes over the course of her two marriages, and she later also signs her work “Camô” and “Daniel Veuve Camô.” For more on women artist’s signatures, see Charlotte Guichard, “Signatures, Authorship and Autographie in Eighteenth-Century French Painting,” Art History 41, 2 (2018): 266-91. This Antillean visual culture includes the work of artists like Agostino Brunias and Le Masurier, identified as such by Anne Lafont in “Fabric, Skin, Color: Picturing Antilles’ Markets as an Inventory of Human Diversity,” Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 43, 2 (2016): 121–54.

[2] Martner herself attempted to submit work to the French Salon in 1802, albeit unsuccessfully. Nathalie Lemoine-Bouchard, “Mme Martner (Paris, 1781-Nancy, 1839), peintre, peintre en miniature et sculpteur aux Antilles,” La Lettre de la Miniature 4 (Dec. 2010): 3; 41-2 (May-August 2017): 2-6; 67 (Sept.-Oct. 2022), 9-11. For more on women artists, miniaturists, and self-portraiture, see Paris A. Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in London and Paris, 1760-1830 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022); Séverine Sofio, “Gabrielle Capet’s Collective Self-Portrait: Women and Artistic Legacy in Post-Revolutionary France,” Journal18 Issue 8 Self/Portrait (Fall 2019).

[3] Kathleen Nicholson, “The Ideology of Feminine ‘Virtue’: the Vestal Virgin in French Allegorical Portraiture,” in Portraiture: Facing the Subject, ed. Joanna Woodall (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997); Joanna Woodall, Self Portrait: Renaissance to Contemporary (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2005).

[4] To date, the box and its contents—including at least eleven portrait miniatures—remain in the care of Martner’s descendants. I am indebted to the family for their kindness, allowing me to visit, photograph, and write about their cherished collection. In addition, I have since recovered several other miniatures by Charlotte Martner, including one at the V&A and a series of portraits of Creole Martinican women sold at auction.

[5] Marcia Pointon, “Surrounded with Brilliants: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England,” The Art Bulletin 83, 1 (2001): 56; Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas, 164, 246.

[6] David Pullins aptly pointed this out to me.

[7] This research forms part of my PhD dissertation at The Courtauld Institute, which examines the history of the portrait miniature in the circum-Atlantic Caribbean (1596-1830). I plan to publish a more extensive article devoted to Charlotte Martner’s practice and body of work in Martinique, developing further some of the ideas proposed here.

[8] During a period of financial distress following the death of her second husband in 1818, Martner kept detailed records of her commissions, earnings, and sitters, including the frequent purchasing of frames and canvas in 1819-1820. These records are part of the family estate.

[9] Jennifer van Horn, Portraits of Resistance: Activating Art During Slavery (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022), 33-8.

[10] Records from the estate sale following Martner’s husband’s passing (1819), part of the family estate. Martner’s financial records between 1818-1821 further show regular payments between “Isidor,” la mulâtresse Adelaide, and Martner, often labelled “renting” or louer—perhaps referring to hired day laborers, a common form of slavery in urban centers like Fort de France.

[11] Van Horn, Portraits of Resistance. Christelle Lozère recently shared with me that in her vital research on the subject she has come across at least one portrait painter in Guadeloupe who had an enslaved apprentice in his workshop.

[12] The miniaturist Girault Gresil, who had worked and advertised in Martinique in 1803, stated as much in an advertisement in the Demerara and Berbice Gazette in 1807, remarking that “a report having been circulated, that the materials used by Mons. Gresil were not adapted for this climate, he begs to leave to state, in opposition to such malevolent rumor, that he has finished many hundreds in this part of the World and West Indies, and never yet had one complaint, though some have been executed upward of 30 years.” Demerara and Berbice Gazette, July 25, 1807.

[13] “Est parti: marron le nègre Maximin, cuisiner, âgé de 25 ans, peau noire, beau & bien fait; il appartenait autrefois à M. Manière, de St. Pierre. Cela qui le fera conduire à la première geôle ou à son maître, M. Martner, à Fort-de-France, sera bien récompensé.”In Gazette de la Martinique, July 6, 1804, 609, accessed at Archives Territoriales de Martinique, Fort de France, April 2023.

[14] “Ce buste très-bien fait est de Madame Martner, artiste, qui peint avec beaucoup succès la miniature et le portrait. Elle réside au Fort-de-France.”In Gazette de la Martinique, November 14, 1804, 51, accessed at Archives Nationales d’Outre Mer, digitized September 2023. Many held the Empress responsible for restoring slavery to safeguard her family plantation.

[15] Here I draw on the methodology put forward in Anna Arabindan-Kesson, Black Bodies, White Gold: Art, Cotton, and Commerce in the Atlantic World (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2021).

[16] Arabindan-Kesson, Black Bodies, White Gold, 21.

[17] See for example Jennifer L. Morgan, Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Black Atlantic (Duke University Press, 2021).

[18] Nicholson, “Feminine ‘Virtue’.”

Cite this note as: Damiët Schneeweisz, “Laboring Likeness: Charlotte Daniel Martner’s Paint Box in Martinique (1803-1821),” Journal18 (December 2023), https://www.journal18.org/7162.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.

Pingback: Contained Assertions: Marie Victoire Lemoine’s Paint Box – by David Pullins – Journal18: a journal of eighteenth-century art and culture