Jacqueline Riding

In the early 1730s the painter Joseph Highmore (1692-1780; Fig. 1) made two foreign journeys. His voyage in 1732 to the Low Countries was his first visit to continental Europe and, as stated by Highmore’s son-in-law John Duncombe, was undertaken chiefly to view the Elector Palatine’s Gallery at Düsseldorf “collected by Rubens, and supposed the best in Europe.” Duncombe continues, regarding Sir Peter Paul Rubens: “At Antwerp also he had peculiar pleasure in contemplating the works of his favourite master.”[1] Highmore returned to the continent two years later, this time to Paris, and his journal for this trip survives.[2]

Fig.1. Joseph Highmore, Self-portrait, c.1730. Oil on canvas, 126.4 x 101 cm. Felton Bequest, 1947, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Image Courtesy of the National Gallery of Victoria.

Highmore spent eleven weeks away from London, departing from the Tower on Sunday 13 June 1734 and returning on Tuesday 24 August.[3] A majority of this time was spent in Paris itself and its environs. Highmore’s unguarded reactions to what he saw, as recounted in this unedited and private format, are by turns extremely admiring and highly critical. Further, the journal recalls what captured Highmore’s particular attention, either in the moment or soon after, and as such the references fluctuate between structured sentences and enigmatic single-word jottings. The prominence of Flemish art, specifically Rubens, in his choice of itinerary and corresponding notations suggests that the Paris trip acted, in part, as an adjunct to his earlier experiences in the Low Countries. However and crucially, given the focus of the present collection of essays, Highmore’s itinerary also demonstrates a specific interest in meeting prominent members of the Académie Royale (located in the Louvre from 1692 onwards) and viewing examples of recent “modern” and contemporary French art. This second strand is my focus here. I will conclude by briefly considering how Highmore’s time in Paris may have influenced his art practice on return.

Before doing so, a note of caution. The complete absence of any reference to significant artists such as Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) and Jean-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), the latter one of the rising stars of the Académie, is curious. Watteau had travelled to London in 1720 as the guest and patient of the prominent English physician and art collector Dr. Richard Mead, and while in Paris, Highmore visited Watteau’s patron Pierre Crozat three times. Furthermore, and in addition to their paintings on view at the Académie, in 1734 Chardin submitted sixteen works to the annual Corpus Christi exhibition – staged at the Pont-Neuf and adjoining Place Dauphine – which was considered a Paris art-world highpoint before the Salons became regular events.[4] In that year the associated Octave feast day (celebrated a week after the feast day of Corpus Christi) fell on Thursday 24 June. Highmore’s lodgings were a short walk away (across the Seine from the Louvre) in the rue Dauphine, and the previous afternoon (Wednesday 23 June) Highmore notes, “saw the Pont neuf &c In ye Ev[e]n[in]g fire works &c.” The first reference for Thursday states simply “Gobelines.”[5] Recent and contemporary French art, including works by Watteau and Chardin, were to provide one model, as I have argued, for Highmore’s subject paintings executed in the 1740s, those after Samuel Richardson’s international literary bestseller Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded (1740-1) in particular.[6] Therefore their omission suggests that the journal, as a record of his visit, is far from comprehensive.

That said, and offering just an indication of the breadth and variety of Highmore’s art-related experiences in the French capital, his recorded schedule included the royal palaces of Bourbon, Palais Royal (twice), Versailles and Marly; the Hôtels Lambert, Bouillon, d’Antin, Richelieu; and several private collections including those of Pierre Dubreuil (twice); Crozat; Cardinal Melchior de Polignac (Hôtel Mézières, rue de Varenne); the duc de Tallard; and either Victor-Amédée de Savoie, prince de Carignan (Hôtel de Soissons), or Biberon de Cormery.[7] Of specific interest here are the two visits he made to the Louvre to see the Académie Royale and his access to the studios of its members Jacques Bousseau, Edmé Bouchardon, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Jean Restout, Nicolas Lancret, Nöel-Nicolas Coypel, Charles-Antoine Coypel, Hyacinthe Rigaud, Nicolas de Largillière and Carle van Loo.

According to brief notes in the journal, Highmore carried correspondence and letters of introduction from at least five associates in London, of which the greatest number were written by Peter Daudé, nephew of the Huguenot mathematician and associate of Sir Isaac Newton, Pierre Daudé (1653-1733).[8] There were also letters from the painter and draughtsman Hubert François Bourguignon, known as Gravelot, and the sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac, who had been a student at the Académie Royale. The Paris-born Gravelot had been resident in London since 1732. On 27 June, Highmore was accompanied by Gravelot’s father to the house of Pierre Dubreuil,[9] and on Wednesday 30 June to another private collection in the ‘Place Royale’ (Place des Vosges), which can now be identified as that of Augustin Blondel de Gagny.[10] Finally, Gravelot probably instigated Highmore’s visit to the studio of his former master, Restout, on 2 July discussed below.

The second art-related letter, from Roubiliac who, like Gravelot, had recently arrived in London, was to Académie professor and sculpteur du Roi, Jacques Bousseau. Highmore spent the afternoon of 19 June with Bousseau, visiting the Palais du Luxembourg, where they “Saw the Gallery of Rubens stayed there near 2 hours” – referring to the Marie de’ Medici Cycle, which Highmore was to return to on 22 July – and then the Sorbonne.[11] The following afternoon Highmore joined Bousseau in the gardens of the Palais des Tuileries.[12] Given the profession of his companion, it is unsurprising that Highmore’s notations at the Sorbonne and Tuileries relate to sculpture: the tomb of Cardinal Richelieu by François Girardon, located within the former, receiving particular praise as “the finest piece of sculpture I have ever seen,”[13] while Tuileries sculptures, including those of Nicolas Coustou, were “marvellously fine tis indeed impossible to describe ’em (& many other things here) particularly unless I wo[ul]d spend all my time in the Descriptions.”[14]

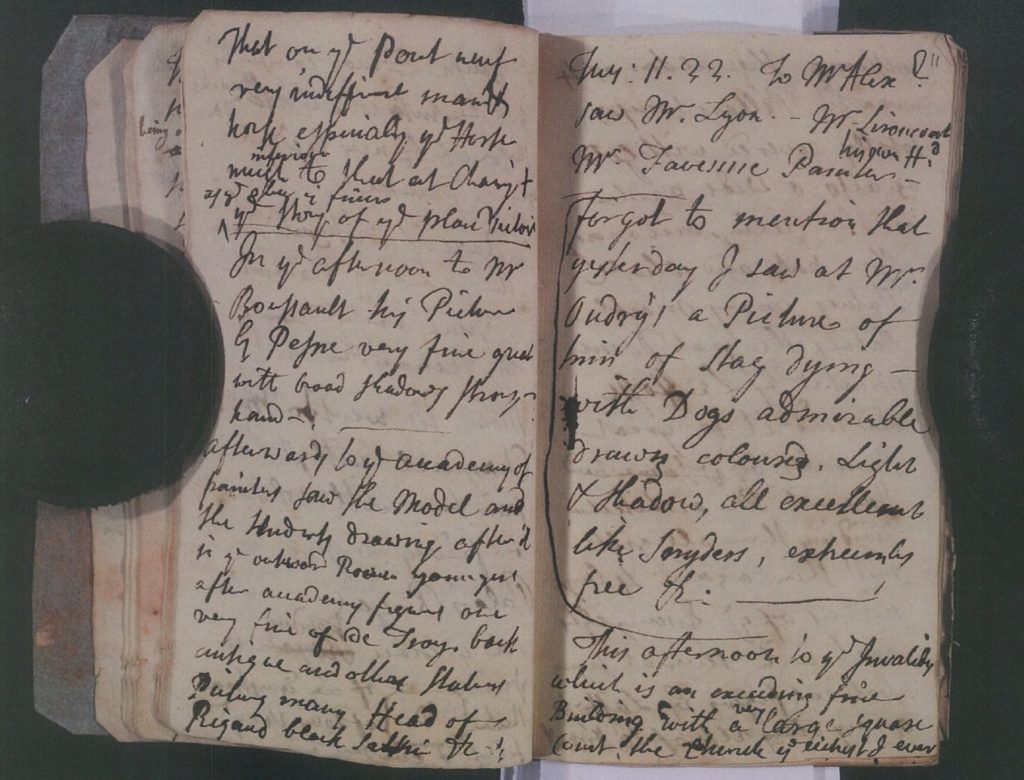

Fig.2. Joseph Highmore, Paris Journal, 1734, Tate Archive TGA 866/2/1, 10 verso and 11 recto. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) © Tate 2016.

The afternoon of Monday 21 June, Highmore met Bousseau in his studio on rue Champfleury near the Louvre, noting only “his Picture” by Antoine Pesne, and then made his first visit to the rooms of the Académie Royale, no doubt with Bousseau as his sponsor and guide. Highmore makes surprisingly few notes during this visit (Fig. 2), and these are both disjointed and at times unclear:

afterwards to ye academy of paint[ing/ers?] saw the Model and the students drawing after it in ye outward Room [young-est, -ers?] after academy figures one very fine of de Troy. back antique and other Statues Pictures many Head of Rigaud black [sattin?] &c.[15]

Highmore clearly begins his description in the école du modéle, where he observes students drawing after a life model. Here too are located casts and “academy figures” (drawings of the model) which, he appears to recall, are the focus for the younger students. The reference to “Troy” immediately after these “statues” may refer to a cast of the Laocoön, although it is more likely that Highmore is making particular note of an “academy figure” drawing by Jean-François de Troy, a professor at the time, then displayed on the wall of the école du modèle and which the Englishman considered “very fine.”[16] Meanwhile “back antique” is probably the Belvedere Torso. A small sketchbook at the Tate, similar in format to the predominantly text-based Paris journal, contains drawings by Highmore of the latter (Fig. 3).[17] It is possible that they were produced during a visit to the Académie, although, considering the ubiquity of such casts, this is speculation. In addition, the sketchbook contains drawings of the Farnese Hercules (Fig. 4), the Borghese Gladiator and some anatomical studies.[18] If Highmore had paused during the Académie tour in order to sketch, then this may explain the lack of commentary in his journal. Alternatively, the paucity of description (as Highmore had already observed) may simply confirm that there was too much to see and do during this visit.

![LEFT: Fig.3. Joseph Highmore, Four Studies of the Belvedere Torso, date not known [1734?]. Pencil, pen and ink and wash on paper, support 35.4 x 23 cm. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) © Tate 2016. RIGHT: Fig.4. Joseph Highmore, Study of the Farnese Hercules, date not known [1734?]. Ink and graphite on paper, support 35.4 x 23 cm. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) © Tate 2016.](https://www.journal18.org/wp-content/uploads/RIDING-Fig3and4-1024x725.jpg)

LEFT: Fig.3. Joseph Highmore, Four Studies of the Belvedere Torso, date not known [1734?]. Pencil, pen and ink and wash on paper, support 35.4 x 23 cm. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) © Tate 2016.

RIGHT: Fig.4. Joseph Highmore, Study of the Farnese Hercules, date not known [1734?]. Ink and graphite on paper, support 35.4 x 23 cm. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) © Tate 2016.

Fig.5. Hyacinthe Rigaud, Martin van den Bogaert, known as Desjardins, 1692. Oil on canvas, 141 x 106 cm. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux.

The afternoon of Friday 2 July, Highmore visited Jean Restout’s “atelier,” located across the Seine from the Académie near Saint-Germain-des-Près, observing that his host’s work had “much sp[iri]t and freedom,” but then, less flatteringly, “col[ou]r[in]g bad, drawing incorrect,” and yet, concluding, “something great in ye whole.”[21] In the same sentence he refers to the Académie professor Nicolas Bertin as having “less [fire?] not much more correctness.” Highmore then states, “afterwards to ye Louvre saw ye Academie again.”[22] On this occasion he refers to Nicolas Poussin’s ceiling painting “Time & Truth” in the Cabinet du Roi as “correct, better col[ou]r[e]d than his ordinary manner. the print is known,” but seems unenthused by the other pictures he saw, writing: “The paintings of Romanelly [Giovanni Francesco Romanelli in the apartments of Anne of Austria] not extraordinary,” while “several other Pictures some originals, some copies but none that struck me much.”[23]

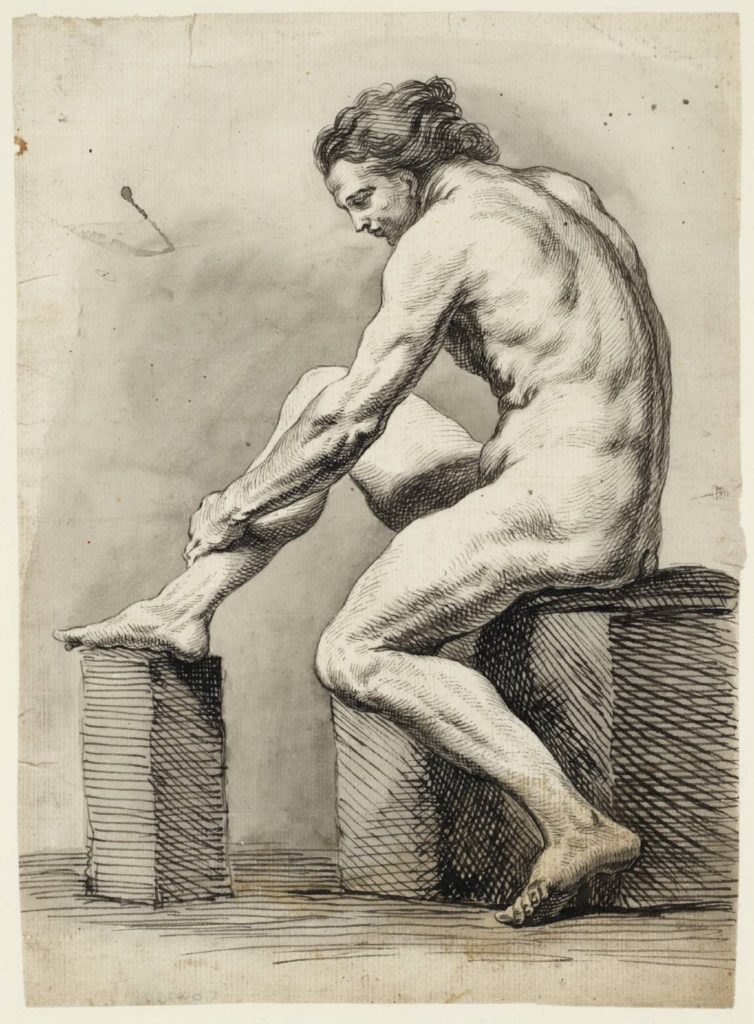

In her transcription of the Paris journal, Elizabeth Johnston suggests that Highmore’s visit in 1734 was a fact-finding mission, with a view to informing the creation of a Royal Academy in London.[24] From 1713 Highmore attended various London artist academies, including the Great Queen Street Academy under the governorship of the German-born Sir Godfrey Kneller.[25] Funded through individual member subscriptions, these academies facilitated drawing from life models (Fig. 6), while acting as forums for the exchange of techniques and ideas, as well as areas relevant to the arts and sciences more generally.[26] It is also worth stressing the cosmopolitan nature of the teaching faculty and membership of these early academies: the Académie-trained Louis Chéron (1660-1725) and Louis Laguerre (1663-1721) were both directors.[27] But whether the early London academy members ever sought to develop beyond an association of self-governing artists to a formal state-sponsored institution on the continental model is debatable.[28] Highmore’s journal offers no comment on the French system of training, nor the opportunities for state/individual patronage, not even, if he were thinking of replication in London, the structure and administration of the Académie.

Fig.6. Joseph Highmore, Academy Study of a Male Nude, date not known. Ink and watercolor on paper, support 23.3 x 17 cm. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) © Tate 2016.

However, Highmore’s high esteem for particular painters who were either founders or products of the Académie is more than evident. The Englishman’s intimacy with the work of Charles Le Brun, for example, is revealed through his observations on, firstly, The Family of Darius before Alexander (c. 1660) then at Versailles, described as the “best picture of Le Brun;”[29] “The great Gallery of Le Brun,” which Highmore considered “not equal to some of his other Works;”[30] and “the famous Magdalen” (1650) at the Carmelite Church, which is “esteemed his Best performance and w[hi]ch is indeed an exceeding fine one but the print (so well known) does him so much justice as to need no description.”[31] After viewing works by Charles de la Fosse at the Hôtel des Invalides—“the great Dome;” “4 large pictures of ye Evangilists” and “many others”—an untraced “raising of Jairus Da[ughte]r” at the Convent de Chartreux, which he considered “much in ye man[ne]r of Rubens;”[32] and Moses Saved from the Waters (dated 1675-1680) at Versailles, Highmore declares La Fosse to be “ye best of all ye French mas[te]rs for Col[ou]r[in]g drapery Composition tout ensemble.”[33] That La Fosse, in Highmore’s opinion, displayed technical traits akin to Rubens may explain his favorable opinion of the Frenchman. Among the examples of contemporary history painting, Highmore noted “the great Oval of Mr Le Moine,” The Apotheosis of Hercules (1733-6). Highmore conversed with François Lemoyne on two occasions while the latter was painting “on his Scaffold” in the Salon d’Hercule within the Grand Appartement du Roi at Versailles, declaring, “I think him the ablest painter I have seen in all respects.”[34]

Highmore had great regard for Hyacinthe Rigaud, as is clear from his journal, as well as the work of Rigaud’s fellow Académie director Nicolas de Largillière, both contemporaries of Chéron and Laguerre.[35] After visiting them at their studios near the Louvre, on the rue de la Feuillade and rue Geoffroy-l’Angevin respectively, Highmore recalled:

the former much more able at present tho’ the other has been an excellent painter of Pourtraits besides w[hi]ch has discovered an extraordinary Genius for History of w[hi]ch many in his House all painted without the life well composed particularly with regard to the lights and shadow in w[hi]ch he has succeeded marvellously and in various manners. Rigaud has also painted of History but very few, more correct than this other but less fire & freedom too much of the lay man. the K[ing]s picture at length hands finely drawn and finished drapery admirably expressed all from laymen.[36]

As Highmore observes, both were known primarily for portrait painting: Largillière’s Portrait of a Family (Fig. 7) is a prime example of the “fire & freedom” in coloring and execution that the English artist so admired. Yet both, as Highmore markedly recalls, had branched out successfully into history painting.

Fig.7. Nicolas de Largillière, Portrait of a Family, c.1730. Oil on canvas, 149 x 200 cm. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Gérard Blot.

What impact did Highmore’s visits to the Louvre, to the Académie, and to its members have on his return to London? As a portrait painter with ambitions for a public career in history painting, it was perhaps Highmore’s encounter with Rigaud and Largillière that galvanized Highmore to turn a private aspiration into a professional reality.[37] Without doubt, and in conjunction with his broader experiences in the Low Countries and Paris, the stimulation Highmore gained through visiting the Académie Royale and engaging with his French peers would have presented a powerful impetus not only to diversify beyond portraiture, but to refresh his portrait practice itself.[38] By 1734 Highmore had been a professional portrait painter for almost two decades.[39] Yet a revised pictorial rhetoric, one that revealed greater ambition in regard to composition, palette, symbolism and overall visual effect is certainly detectable from the mid-1730s, and perhaps best demonstrated by his most complex and large-scale portrait The Family of Sir Eldred Lancelot Lee (Fig. 8) of 1736. Finally, the introductions in Paris that Highmore’s contacts in London facilitated, the depth and breadth of access they provided, and the perceivable warmth and generosity he received during his stay, clearly places him within a dynamic international artistic fraternity: one whose practitioners, connections, ideas and influences continued to flow, back and forth, between the two capitals.

Fig.8. Joseph Highmore, The Family of Sir Eldred Lancelot Lee, 1736. Oil on canvas, 243.8 x 289.6 cm. Wolverhampton Art Gallery Image © Wolverhampton Arts and Culture.

Jacqueline Riding is Associate Research Fellow at the School of Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London

Acknowledgments: My thanks to Hannah Williams for inviting me to contribute to this issue and for providing information on the location of artists’ studios; and, with reference to images, to the National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne, Australia), Tate (UK) and Wolverhampton Art Gallery (UK) for their generosity.

[1] John Duncombe, “Memoirs of the late Joseph Highmore,” The Gentleman’s Magazine 50 (April 1780), 176-179, 177.

[2] Tate Archive 866/2/1, Joseph Highmore’s Paris Journal, referred to henceforth as PJ. Elizabeth Johnston’s published transcription remains a good introduction to Highmore’s itinerary; see “Joseph Highmore’s Paris Journal,” The Walpole Society 42 (1970), 61-104; also Alison Shepherd Lewis, Joseph Highmore: An Eighteenth Century English Portrait Painter, 3 vols. (PhD dissertation, University of Harvard, 1975), I, 114-133. A new transcription and full reanalysis of the journal, with additional information and identifications, was undertaken for my doctoral thesis, elements of which form the core of this article; see Jacqueline Riding, Joseph Highmore 1692-1780, 2 vols. (PhD dissertation, University of York, 2012), I, 94-127.

[3] PJ, 2r and 37v. Great Britain was still using the ‘Old Style’ Julian calendar, which was 11 days behind the ‘New Style’ Gregorian calendar prevalent in mainland Western Europe. Highmore records both dates simultaneously, a habit of British travellers at the time. For clarity only ‘New Style’ dates have been included here.

[4] Mercure de France (June 1734), 1405; and Robert Berger, Public Access to Art in Paris (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), 149-150.

[5] PJ, 14v-15r.

[6] Riding, Joseph Highmore, I, 188-220.

[7] Not the Comte de Fraula as suggested by Johnston, “Joseph Highmore’s Paris Journal,” 99, n. 78.

[8] Peter Daudé commissioned Highmore’s portrait of his uncle, which he then donated to the London French Hospital. His friendship with Daudé places Highmore directly within the orbit of the Huguenot intellectuals that gathered at Old Slaughter’s Coffee House in Covent Garden, including the journalist and editor Pierre de Maizeaux (1672/3-1745). One of Highmore’s earliest extant portraits is of the Huguenot ivory carver David Le Marchand; see Charles Avery, David Le Marchand 1674-1726 “An Ingenious Man for Carving in Ivory” (London: Lund Humphries, 1996); and Jacqueline Riding, “A Session of Painters: Legacy, Succession, and the Prospects for British Portraiture after Kneller,” in Mark Hallett, Nigel Llewellyn and Martin Myrone, eds., Court, Country, City: British Art and Architecture, 1660-1735 (New Haven and London: Yale Center for British Art/Paul Mellon Centre, 2016), 353-379, 366-379. For Highmore’s connections with the London Huguenot community and details of his associated activities in Paris see Riding, Joseph Highmore, I, 111-114.

[9] Johnston, “Joseph Highmore’s Paris Journal,” 99, n. 88.

[10] Riding, Joseph Highmore, I, 109.

[11] PJ, 3v–5v, 6r, 28v.

[12] PJ, 9r–10r.

[13] PJ, 6r-6v.

[14] PJ, 9v.

[15] PJ, 10v.

[16] My thanks to Hannah Williams for this clarification.

[17] T04233, see also T04234.

[18] T04235, see also T04236 and T04237.

[19] Highmore saw this statue, PJ, 10v.

[20] See Hannah Williams, Académie Royale: A History in Portraits (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 130-131.

[21] PJ, 21v.

[22] PJ, 21v.

[23] PJ, 22r.

[24] Johnston, “Joseph Highmore’s Paris Journal,” 67-68.

[25] See Riding, Joseph Highmore, I, 31-33, 35-38.

[26] Academy Study T04230, see also T04231.

[27] Highmore owned two paintings by Laguerre, probably designs for large painted schemes: “Diana and Endymion” and “Curtius leaping into the fiery Lake,” both untraced. See Abraham Langford, A Catalogue of the Genuine and Entire Collection of Pictures of Mr. Joseph Highmore (Langford: London, 1762).

[28] See Ilaria Bignamini, “Art Institutions in London, 1689-1768,” The Walpole Society 55 (1988), 1-148.

[29] PJ, 24v.

[30] PJ, 25r.

[31] PJ, 16v-17r.

[32] PJ, 11v–12r.

[33] PJ, 25r.

[34] PJ, 26r–26v.

[35] As a young man Largillière had been employed for four years as an assistant in the London studio of Sir Peter Lely (d. 1680), returning to the city in 1685–6. For a discussion of Highmore and Largillière see Jacqueline Riding, “Artistic Connections between Dublin and London in the Early-Georgian Period – James Latham and Joseph Highmore,” in Jane Fenlon, Ruth Kenny, Caroline Pegum and Brendan Rooney, eds., Irish Fine Art in the Early Modern Period: New Perspectives on Artistic Practice, 1620-1820 (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2016), 80-117, 101-102.

[36] PJ, 29v–30r.

[37] See Jacqueline Riding, “‘The mere relation of the sufferings of others’: Joseph Highmore, History Painting and the Foundling Hospital,” Art History 35:3 (2012), 522-553.

[38] For The Lee Family see Riding, Joseph Highmore, I, 144-159. In contrast, Shepherd Lewis perceived little change in Highmore’s portraiture or subject painting, claiming that “Direct and specific influences of Highmore’s Paris experience on his painting are difficult to find.” See Shepherd Lewis, Joseph Highmore, I, 133.

[39] For Highmore’s early career see Shepherd Lewis, Joseph Highmore, I, 21-41; Riding, “A Session of Painters”, 353-366; and Riding, Joseph Highmore, I, 31-93.

Cite this article as: Jacqueline Riding, “An Englishman in Paris: Joseph Highmore at the Académie Royale,” Journal18, Issue 2 Louvre Local (Fall 2016), https://www.journal18.org/841. DOI: 10.30610/2.2016.3

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.