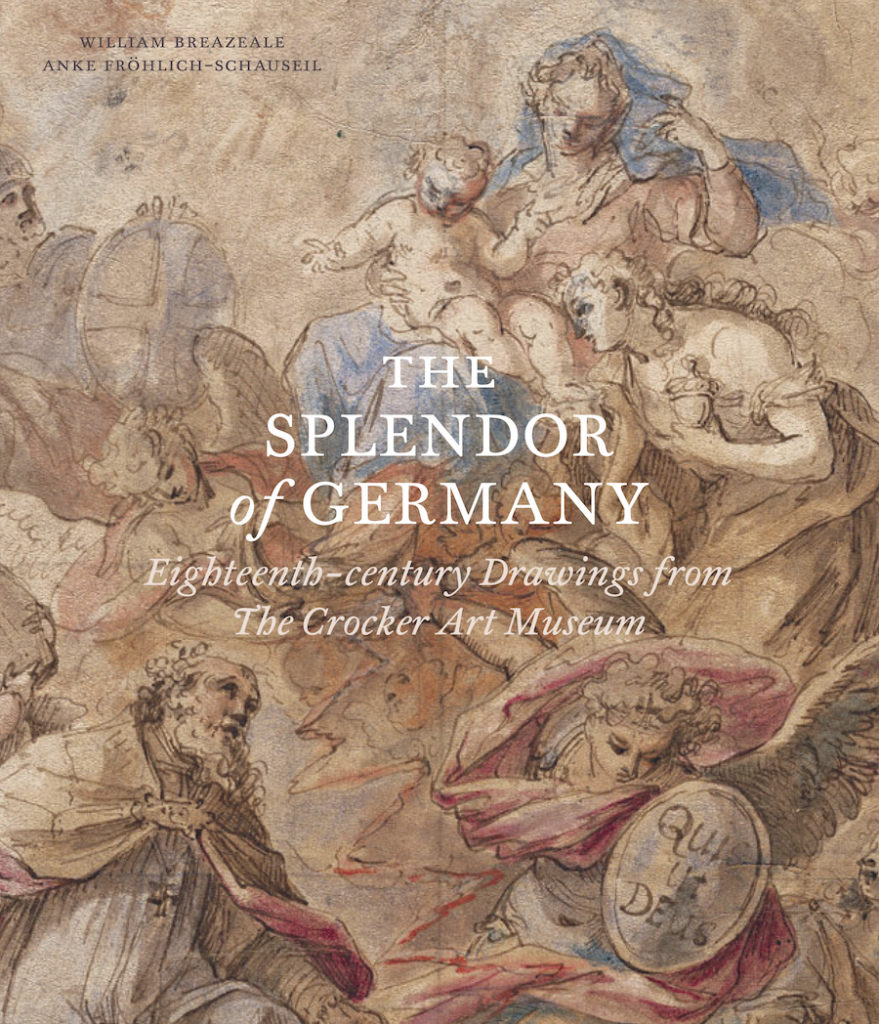

William Breazeale and Anke Fröhlich-Schauseil, The Splendor of Germany: Eighteenth-Century Drawings from the Crocker Art Museum (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2020)

Only those fortunate enough to live in or visit Sacramento, California, will have had the pleasure of browsing the collection of the Crocker Art Museum—a cultural hub of the city created from the mansion and collection of the nineteenth-century family of Judge Edwin Bryant Crocker. Among the gems of the collection is a large group of eighteenth-century drawings from German-speaking states which are the subject of this scholarly catalogue. Co-written by Crocker curator, William Breazeale, and Anke Fröhlich-Schauseil, a specialist in the art of Saxony, the catalogue builds on the formative research of Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann on central European drawings, and nudges forward some of his conclusions about specific works in the collection. While the catalogue is a meticulous work of connoisseurship that introduces readers to many unfamiliar and sometimes fascinating drawings, the authors occasionally sacrifice broader conclusions in their focus on detailed analysis.

The selection illustrated and discussed in this catalogue is a small sample of over 1000 drawings in the Crocker collection. These were most likely brought back to Sacramento after an extensive stay in Dresden by Edwin and Margaret Crocker and their children in 1869. The drawings represent a variety of artists who worked in German-speaking states during the last decades of the eighteenth century and the early decades of the nineteenth. Apart from familiar names like Anton Raphael Mengs, Daniel Chodowiecki, and Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, many of these artists are likely to be new to English-speaking audiences.

Through their two essays and entries on 41 drawings, the authors navigate a wide range of topics: the history of the Crocker collection, a close study of the technique of each individual work, some background on the artists, and observations about networks of artists and dealers both in the eighteenth century, when the works were produced, and in the late nineteenth century, when the collection was formed. Frölich-Schauseil’s overview of the Dresden art world in the late eighteenth century provides useful background material on the extraordinary group of individuals who congregated in Dresden before, during, and after the Seven Years’ War. Her essay is pitched for the general reader, while Breazeale’s contribution on networks of artists and dealers is painstakingly focused on inscriptions, collectors’ marks, and provenance, which speaks more to the specialist. After these two introductory essays, the catalogue itself is divided into two sections: “German Visions” and “Visions of Germany,” the latter of which focuses entirely on landscape drawings.

Both authors step back from taking a broader overview of the period in which these artists worked: “The drawings… are considered on their own terms, rather than playing their usual role as modest precursors to a more glorious Romantic period (9).” This decision to focus on close study of the works rather than sweeping historical generalizations, for example about the rise of European Romanticism, has its merits, although I found that the individual entries raised intriguing questions about how the German art world functioned in the late eighteenth century, the cosmopolitanism of many of the artists, and the eclecticism of both style and subject matter of the selected drawings.

The medieval system of apprentice, journeyman, and master seemed to linger in the working practices of many of these artists, who more often than not were the sons and daughters of artists or other craftspeople. Notably, most of them travelled between German courts seeking patronage before locating a sponsor for the all-important trip to Italy, an aspiration of many European artists as a means of studying the best of ancient and Renaissance art. Nearly all of these artists moved one or more times, and although Dresden certainly was a crucial center, others worked in Augsburg, Prague, Weimar, Frankfurt, Mannheim, Vienna, Hamburg, and Zurich. While Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Mengs became important magnets for a large network of German artists in Rome, there were others who went to Paris instead and became part of an alternative circle under the leadership of the German expatriate engraver Johann Georg Wille. Some of these artists were attracted to the liberal ideals that characterized Enlightenment academies throughout Europe, but most of them were producing drawings as preparatory works for prints to sell in the lucrative European print market.

The drawings themselves are varied in subject matter, style and technique. There are significant contrasts, for example, between Mengs’ lavishly crafted Death of Dido (Fig. 1); Georg Melchior Kraus’ spare Peasant Woman Eating; Heinrich Friedrich Füger’s Lais and Socrates (based not on an ancient text but a modern epistolary novel); and Johann Elias Ridinger’s Aesopian A False Friend is Worse than an Open Enemy. Dutch influence is strong in many of the works, but Johann Eleazar Zeissig (called Schenau) was known as the “Greuze of Saxony,” and Chodowiecki’s The Improvement of Morals comes right out of the stable of William Hogarth. The authors have excellent discernment when it comes to characterizing the technique of the individual artists, who used brush, pen and ink, watercolor, and chalk to create a variety of effects—from the multiply diluted ink used to form the shadows around the nose in Johann Gottlieb Prestel’s Self-Portrait, to the poetic stippling that characterizes Christoph Nathe’s Landscape in Lusatia. Many of these drawings are studies for prints, and the two scholars have done a punctilious job locating variants in collections all over Europe.

The final section of the catalogue includes a range of landscape drawings which gives the reader a strong sense of the poetic aesthetics that would influence Caspar David Friedrich, although the catalogue entries do not overplay this narrative. Saxony was a mining region, and the geological formations there provided fascinating fodder for drawings such as Johann Alexander Thiele’s A Marble Crag of 1746. The ‘Malerweg’ of Saxon Switzerland that was the subject of Adrian Zingg’s drawings became a hot spot for Picturesque tourism in the years to follow.

Overall, this catalogue provides an intriguing glimpse into the range and importance of drawing to German-speaking artists of the late eighteenth century. Its assiduous scholarship will make it an indispensable addition to the shelves of auction houses, while it provides the interested reader with insights into a collection that many may never have the opportunity to see.

Shearer West is Vice-Chancellor and President of the University of Nottingham

Cite this note as: Shearer West, “The Splendor of Germany: A Review,” Journal18 (August 2020), https://www.journal18.org/5113.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.