Ana Lucia Araujo

Historians and art historians have increasingly explored the role of material culture and gift exchanges in the context of the transatlantic slave trade.[1] A number of these studies have paid particular attention to the role of prestige gifts in the commercial and cultural exchanges between Africans and Europeans in the context of the inhumane trade.[2] Drawing on my previous work, this article aims to offer a small contribution to this scholarship, by interrogating the role of gifts of prestige during the era of the Atlantic slave trade in West Africa and West Central Africa. To do so, I revisit the case of a silver sword of prestige (kimpaba), which was crafted in the French slave-trading port of La Rochelle. In 1777, French slave traders transported the sword to Cabinda, where it was presented as a gift to Andris Pukuta, a Mfuka (royal agent). More than a century later, in 1892, the French military looted the sword in Abomey, the capital of the West African Kingdom of Dahomey.

Whereas my recent book The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism (2024)followed the trajectory of this silver kimpaba from France to Cabinda, from Cabinda to Abomey, and from Abomey back to France, this article is an opportunity to delve deeper. Made of iron, wood, ivory, copper, and silver, such swords featured a variety of formal elements that carried various symbolic meanings across time and space. I seek to understand how a related corpus of swords—made in West Africa, West Central Africa, and Europe, and now held in European and North American museums—functioned as commemorative gifts of exchange among African and European rulers, traders, and other intermediaries to facilitate the trade in enslaved Africans. How did these prestige objects produced in the context of long-lasting commercial and cultural exchanges between Africans and Europeans impact the peoples and societies involved in these interactions? How were these exchanges, which were shaped by the trade in human beings, imprinted on these gifts of prestige, and how did they transform their materiality and designs? This essay attempts to answer these questions.

The Genesis of the Eighteenth-Century French Kimpaba

The eighteenth century was the most intensive period of the Atlantic slave trade. French slave vessels sailed to Atlantic Africa to purchase enslaved Africans, which they transported mainly to the French West Indies, especially Saint-Domingue, the most important producer of sugar in the Americas during this period. Many French slave merchants who sailed from various French ports such as Nantes, La Rochelle, Bordeaux, Le Havre, and Lorient, anchored in ports located along the Bight of Benin, the coastal area of today’s Togo, the Republic of Benin, and Nigeria. Many other vessels went to trade farther south on the Loango coast, the region stretching north of the Congo River in what is today Angola and the Republic of the Congo. In West Central Africa, the Loango coast encompassed three major states: the Kingdom of Ngoyo, whose main port was Cabinda, in today’s Angola; the Kingdom of Kakongo, whose slave-trading port was Malembo, just a few miles north of Cabinda, also in today’s Angola; and the Kingdom of Loango, the largest of the three kingdoms, whose main port was Loango, in today’s Republic of the Congo.

These three states had a noble class, including a king, whose agents occupied different offices. In the three ports of the Loango coast, one of the king’s agents was the Mfuka, whoEuropeans often described as the minister of commerce. The Mfuka resided at the coast and controlled the trade in enslaved Africans. He imposed the sale of captives acquired through his trading networks on local brokers and waived taxes on selected European merchants who came to the coast to purchase enslaved Africans. In return, European slave traders offered these agents gifts. Such gifts contributed to increasing the wealth of the individuals who held the office of Mfuka during the rise of the Atlantic slave trade on the Loango coast in the eighteenth century until its decline in the middle of the nineteenth century. Although European traders often offered gifts to African agents, these were usually the same articles with which traders purchased enslaved Africans, including various kinds of alcohol, several types of textiles, rifles, gunpowder, and manufactured items such as clothing items and pieces of metalware. But prestige gifts were objects of higher quality than mere exchange goods.[3]

As they did in other parts of Atlantic Africa, European merchants traveling to the Loango Coast began bringing prestigious items—such as swords, crowns, thrones, and scepters—to present as gifts to African traders and rulers.[4] Gifts of prestige were made of materials that Europeans and African agents perceived as being precious and rare. These objects were special items because their forms carried symbolic meaning to the gift givers and receivers. After all, swords, crowns, thrones, and scepters were royal and religious insignias intended to be held by individuals who occupied particular offices and therefore held political power. As European traders interacted and spent months on the African coasts, they learned the tastes and preferences of their African counterparts. Thus, when French ship captains left ports such as La Rochelle, Bordeaux, Le Havre, and Nantes and sailed to the Loango coast to trade in ports such as Cabinda, Malembo, and Loango, they brought goods specifically chosen to appeal to African agents since they corresponded to their preferences.

In June 1775, the French slave ship Le Montyon, followed by the corvette L’Hirondelle, sailed from La Rochelle to the Loango coast. Jean-Amable Lesenne was the captain in charge of Le Montyon, and Jacques Cousse was the captain of L’Hirondelle. Daniel Garesché, a very rich shipowner, slave trader, and future mayor of La Rochelle, outfitted and owned the two vessels. Once the vessels anchored in Malembo, Cousse and some of his crew members went to trade in Cabinda, where they were attacked by other French ship captains from Bordeaux and Le Havre. Such conflicts were not uncommon, as European ship captains who sailed to this region to purchase enslaved Africans to transport them to the Americas were competing with each other to obtain the best captives for the best prices. The Cabinda’s Mfuka,Andris Pukuta, protected the assailed slave traders from La Rochelle by sheltering them in his house.[5]

After the conflict in Cabinda, Lesenne (the captain) and Garesché (the shipowner) were certainly grateful to the Mfuka Andris Pukuta for having protected their lives. Back in La Rochelle, either Lessene or Garesché, or both, commissioned the production of a solid silver ceremonial sword to be offered as a gift to the Mfuka during their next slaving voyage to the Loango coast. The origin of the sword in La Rochelle is attested by the presence of several hallmarks, confirming the date and place of manufacture. Though there is no hallmark validating the name of the master silversmith who made the sword, only twelve silversmiths were working in La Rochelle in 1775.[6] The most important of them was Jean-Baptiste Chaslon. By comparison with formal elements of other silver items created by him during the same period, as well as existing written records, there is little doubt that Chaslon manufactured the silver sword (Fig. 1).

Yet, the evidence goes beyond formal features. In my research in French archives, I found a ship surgeon named Louis Chaslon who traveled on board Le Montyon in 1775, when the conflict took place, and again in 1777, when the silver sword was offered as a gift to the Mfuka Andris Pukuta.[7] Louis Chaslon was none other than the brother of Jean-Baptiste, and perhaps was among Lessene’s men who spent the night sheltered at his house after being attacked by rival slave traders. Such connections were anything but surprising. The trade in enslaved Africans was a lucrative business involving entire families on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

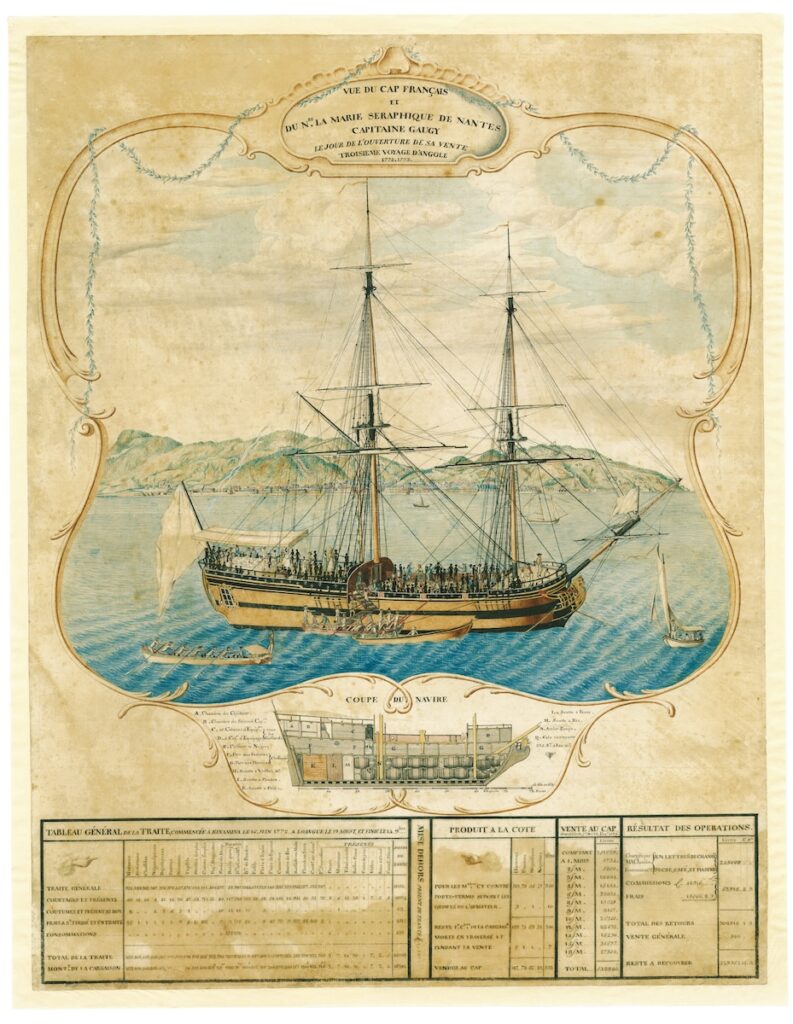

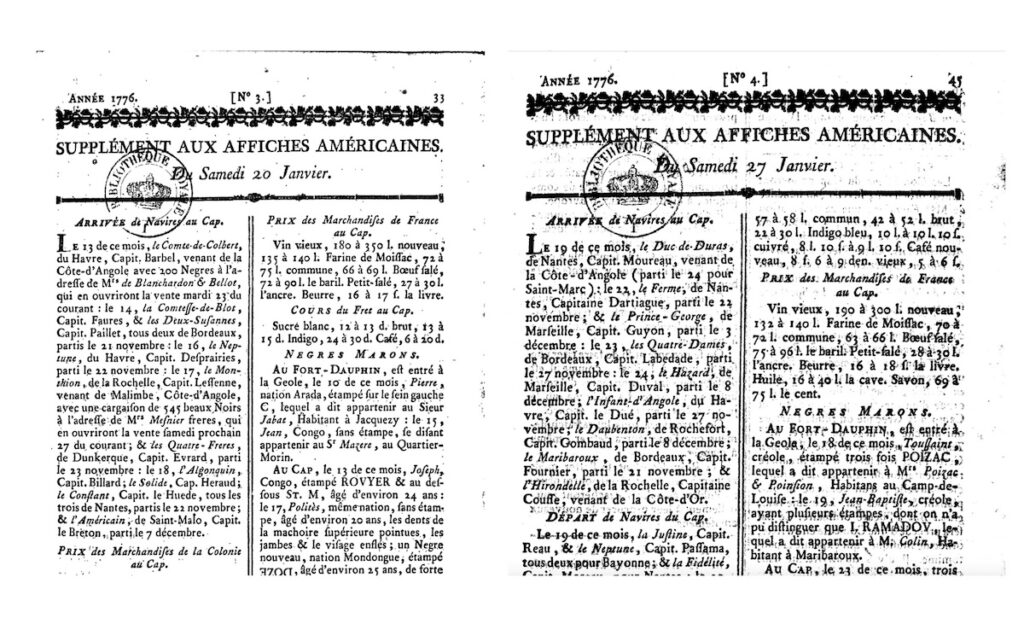

Both sides of the silver ceremonial sword manufactured in La Rochelle are identical and feature formal elements similar to other French eighteenth-century silverware. For example, the sword’s gadrooned handle evokes the fluted caps of a pair of silver oil bottles by Jean-Baptiste Chaslon. In addition, the opulent garland featuring floral motives engraved on the blade was also a very common decorative element in eighteenth-century paintings, watercolors, and silver objects. Since antiquity, garlands of flowers and leaves have been used to honor individuals and commemorate particular events—therefore over the centuries, in addition to symbolizing honor, the visual representation of floral garlands was intended to convey the idea of victory. For example, a watercolor depicting the French slave ship La Marie-Séraphique (Fig. 2), which sailed from Nantes to Loango a few years earlier before transporting over three hundred African captives to Saint-Domingue, is also framed by garlands (Fig. 3). These decorative elements likely symbolize victory—specifically, the triumph of slave merchants who successfully completed a slave voyage. Hence,it is likely that the garland engraved on the silver sword from La Rochelle also represented the profitable slave voyage of Le Montyon and L’Hirondelle. After all, despite the attacks by other French traders, the two vessels safely completed the purchase of hundreds of African captives and transported them to Saint-Domingue, thanks to the Cabinda’s Mfuka. This is confirmed by two announcements in the newspaper Affiches américaines (Fig. 4).[8]

Finally, the silver sword bore a particularly significant feature: a striking dedication engraved on its unsharpened tip, proclaiming “Andris Macaye Mafouque le juste de Cabinde.” This inscription unequivocally designated Mfuka Andris Pukuta as “the righteous of Cabinda”—a powerful acknowledgment of his pivotal role in rescuing the slave traders from La Rochelle in 1775 (see Fig. 1).

Bimpaba as Cross-Cultural Swords of Prestige

Despite having been created and manufactured in La Rochelle, the French silver sword’s format and some of its decorative elements differed from existing French ceremonial swords. The French sword’s format is similar to that of a kimpaba (plural bimpaba), a sword of prestige that existed in the kingdoms of Kongo, Loango, Kakongo, and Ngoyo, where Cabinda was located. Locally made bimpaba were usually manufactured in wood (Fig. 5) and iron (Fig. 6), even though surviving examples were likely manufactured in the nineteenth century (Fig. 7). According to the typology established by Tristan Arbousse Bastide in his examination of African traditional weapons, the kimpaba is part of the wider category of chopping knives. These “short-bladed weapons” have very distinctive shapes. Measuring between fourteen to twenty-eight inches, their blades are wider than those of the cutlasses, and they are used as both symbolic and practical weapons.[9]

Originally these bimpaba were part of the regalia of the king of Ngoyo (maningoyo), even though, as we will see, their role was transformed with the intensification of the Atlantic slave trade on the Loango coast in the eighteenth century. A kimpaba was also designated as kimpabala. In Kikongo the term ki-mpa is defined as a “story game, entertainment, trick, enigma, mystery.”[10] Anthropologist Carlos Serrano also suggests that the word kimpaba possibly derives from the verb kimpakubala, which in Kikongo means “power or faculty of becoming invisible.”[11] Depending on the European language, the Kikongo word kimpaba has been transliterated in various ways, resulting in terms such as kimpada, ximpaba, cimpaba, chimpaba, chimpava, or tshimpaba. These variations stem from the different phonetic and orthographic systems of European languages interacting with local Bantu languages in the region.

Emulating the sword carried by the Ngoyo ruler, the Maningoyo, these prestige swords or scepters embodied the power of their holders. Yet, the very existence of bimpaba that served as a model for the fabrication of the silver kimpaba from La Rochelle suggests that, as early as the late eighteenth century, other Woyo dignitaries also held this insignia. [12] Like other objects of prestige owned and displayed by rulers in West Central Africa and West Africa such as cloths, sandals, thrones, parasols, and scepters, Woyo rulers also had several royal insignias such as the drum (ndungu ilu), three elephant tusks (zimpungi), double bells (ngongie), skin of ngola-nhundu (an otter of sorts), leopard skin (ngó), cat skin (sinzi), and royal cap (nzita), each of these royal items being associated with different proverbs. The kimpaba was one of these emblems, intended to assert and display the special status of these dignitaries.[13]

According to French officer and slave merchant Louis-Marie-Joseph Ohier de Grandpré, who visited the Loango Coast in the 1780s—just a few years after Garesché’s agents presented the kimpaba to the Mfuka of Cabinda—the Manibele, an agent of Loango’s ruler (the Maloango), displayed a copper ceremonial knife as a symbol of authority. He writes, “this knife was made of copper before the arrival of the Europeans who then had them make it out of silver. I don’t know why they call this instrument a knife, it has nothing to do with those we call that way; but as they designate it as belé, I had to translate it as knife.”[14] As Zdenka Volavka explains, the term mbele refers to a variety of “profane and ceremonial knives, daggers, and swords of various sizes and shapes.[15]

Portuguese Catholic priest José Martins Vaz, who lived and worked as a missionary in the archdiocese of Luanda for nearly one decade starting in 1948, stated (probably drawing from Grandpré) that the mbele lusimbu (chief’s knife) was used in death sentences and had always been a symbol and instrument of a chief’s discretionary power.[16] He underscored that during the era of the Atlantic slave trade these knives were replaced with the kimpaba, and slave traders even gave heavy versions made of silver to local chiefs. Hence, these swords with blunt edges were no longer used for capital executions but only to symbolize the king’s absolute power.

Scholars associate the bimpaba with these traditional medium-sized curved single-edge swords of prestige found among the Kongo peoples and known as mbele a Ne Kongo or mbele a lulendo. The handles of these swords were usually shaped like zoomorphic figures such as crocodiles and lions and anthropomorphic shapes such as human heads and hands.[17] Indeed, the blades and handles of traditional bimpaba were made of iron, copper, wood, and plumb. Therefore, despite Grandpré’s statement, it seems likely that the greater European presence on the Loango coast during the second half of the eighteenth century led to the introduction of silver-made mbele and bimpaba. Yet, as confirmed through swords of prestige preserved in museum collections today, more often materials other than silver continued to be employed in their manufacture.

As royal insignia, the bimpaba were intended to underscore the political and supernatural powers of the kimpaba’s holder. They preceded the ruler and embodied his presence even in his absence. Therefore, they were also displayed in official meetings, including assemblies to decide judicial cases. A particular feature of these swords of prestige is the variety of shapes that arise from their blades. Yet, there is no single interpretation for these symbols as they acquired different meanings depending on the context, representing people, houses, plants, animals, and shells that offered a “vocabulary to the chief, who would interpret these pictograms with proverbs, according to the needs of the moment.”[18]

Existing studies of Woyo symbolism offer some clues to understanding the possible meanings of the geometrical shapes decorating these swords. According to ethnographer and priest Joaquim Martins, the jagged semicircle evokes the sun (Ntangu). Among the Woyo, this symbol refers to a commoner, who “presented himself everyday as the sun usually does,” because nobles such as the Maningoyo (or ruler) hide “from others’ sight and from contact with the commoners.”[19] Thus, the presence of a sun symbol in the openwork of a kimpaba would suggest that its holder was a commoner or at least convey a message evoking the kingdom’s commoners. Meanwhile, the triangle symbolizes the crocodile, whereas the semicircle represents the moon (as seen in Fig. 6) and therefore evokes the ruler, who should not be seen or exposed to public scrutiny. Moreover, the wooden bimpaba (as seen in Fig. 5) allowed it to convey additional messages through color. Here, the use of red and white symbolizes life, death, and regeneration. The handles of these swords could be made of the same material as the blade as we can see in the two wooden bimpaba (Fig. 5 and Fig. 7, on the right), even though the ones manufactured in iron could have handles of other materials such as wood and ivory. Several bimpaba feature handles representing animal and human heads as well (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

As swords of prestige and objects of power, bimpaba functioned as “speaking objects” that “addressed a reader outside themselves,” conveying a narrative composed of geometric symbols used to communicate existing proverbs usually associated with a particular clan or village.[20] Other objects of Woyo material culture, such as wooden pot lids, also featured pictograms that, when combined, conveyed proverbs associated with clan chiefs. Interestingly, many of these pot lids also depict bimpaba, creating a layered, self-referential narrative.

Bimpada were not static objects. Their formats, formal elements, and meanings were transformed over time, as the West Central African societies where they were created, and their peoples changed too. As a result, if the bimpaba were once royal insignia, during the eighteenth century, and especially in the nineteenth century, these swords of prestige became part of the Mfuka’s regalia, even though he was a man without royal status. That a commoner could hold a kimpaba seems to reflect the transformations provoked by the growth of the Atlantic slave trade in the eighteenth century, when more Woyo agents were playing the role of intermediaries between the king and European traders and, consequently, acquiring increasing wealth and political power.

Despite being made in La Rochelle, the silver kimpaba is in dialogue with the bimpaba created in West Central Africa. Moreover, regardless of existing similarities, upon reaching Cabinda, the silver kimpaba was not a simple French reproduction of West Central African bimpaba, but was rather an Afro-European object. The French sword’s design, format, and size, as well as formal and symbolic decorative elements such as the garlands and the written dedication, embody the Atlantic commercial and cultural exchanges among the French and Woyo peoples. The sword also includes symbols carrying cross-cultural significance. Like other Loango coast bimpaba (Figs. 5-7), the kimpaba from La Rochelle includes openwork ornamentation consisting of eleven geometrical figures. However, whereas in the West Central African bimpaba the shapes were cut out from the false edge, in the French silver version (Fig. 1) the openwork was added to the blade. Like very delicate and small rings, these figures consist of a jagged semicircle, sets of two equilateral triangles with confronting tips, one right triangle, a straight vertical line (possibly what remained from a triangle shape), and a circle. These shapes reference pictograms found on bimpaba from the Loango coast. However, I argue that the openwork on the false blade and the cross carved at its tip were likely not part of the original sword manufactured in La Rochelle. Instead, these elements were added later—not in Cabinda, where the sword was gifted to Mfuka Andris Pukuta, but much farther away in Abomey, from where it was looted in 1892.

Understanding the context in which the French-made silver sword was produced, along with its formal and symbolic connections to bimpaba from West Central Africa and other West African swords, helps clarify the uniqueness of its openwork design. The activities of the Mfuka Andris Pukuta survived in the written archive following the documented conflict among French slave traders in Cabinda in 1775.[21] Moreover, in his travel account Grandpré, who traded in Cabinda and Malembo in the 1780s, provided first hand evidence about Pukuta’s inhumation, which probably occurred in 1786, during the first year of his stay in Cabinda. Among others, Grandpré explained how complex and long were the funerary rituals of the important men on the Loango coast. First, the body was emptied of its organs, parched, and coated with a thick layer of red earth. Next, precious belongings of the deceased were added to his corpse and then wrapped in a bundle whose size was proportional to his wealth and importance and composed of numerous layers of different kinds of cloth, before eventually being buried. Confirming Pukuta’s importance, Grandpré explained that the performance of all of his funerary rituals, including wrapping his corpse to form the giant bundle, lasted an entire year.[22]

Despite Grandpré’s description, it is unlikely that the silver kimpaba made in La Rochelle was buried with Pukuta. On the one hand, the sword was a valuable object, and despite having been manufactured in France, it was part of the Mfuka’s regalia. Moreover, Pukuta likely had other insignia, and it is not excluded that he had at least another locally made sword of prestige. Later ethnographic studies describe how these insignia were passed down to the deceased’s successor, therefore suggesting that the silver sword was likely displayed among Andris Pukuta’s belongings during his funeral and then transferred to his successor.[23]

Regardless of these details, after Pukuta’s death, the silver kimpaba was taken from Cabinda and possibly brought back to La Rochelle, from where it was likely transported to Ouidah, perhaps through Porto-Novo, from where it was carried to Abomey, the capital of the powerful Kingdom of Dahomey in West Africa.[24] In Abomey, the sword was incorporated into the collections of the royal palaces, which included other prestigious items manufactured locally as well as objects from Europe, Asia, and the Americas.[25]

Traveling Kimpaba

The migration of the silver kimpaba to Abomey raises questions regarding the geometric symbols on the sword’s blade. Here, I argue that the openwork was added to the blade in Abomey for two main reasons. First, the practice of amending silver objects to adorn them is found in West African societies. Second, there were established silversmith workshops in Abomey, where the smiths of the Hountoundji family created and manufactured a panoply of silver objects that combined European and West African elements.

The kimpaba’s added openwork (Fig. 9) includes eleven symbols divided into three sets. The first and longest set of signs consists of one jagged semicircle, two equilateral confronting triangles, one equilateral triangle, one jagged semicircle, one circle, and one right triangle. The second group of symbols is composed of two more confronting equilateral triangles and one jagged semicircle. Finally, the third series consists of a straight vertical line (probably what was left of a right triangle), a circle, and a final set of two confronting equilateral triangles. Some of these geometric forms are comparable to the cutout figures found in Fon ceremonial swords known as gubasa (the symbol of the vodun Gu, the Fon god of war and metal) represented in several Fon artworks, including an anthropomorphic sculpture (Fig. 10) that was also looted from Abomey in 1892.[26]

The Gu iron sculpture is in dialogue with the silver kimpaba, because in addition to diamond shapes, the huge gubasa held by the iron warrior bears circle shapes as well as two confronting triangles, a symbol evoking the double-bladed axe associated with Hɛvioso, the vodun of thunder, an equivalent of the orisha Ṣàngó in the Yoruba pantheon. Meanwhile, the jagged semicircle symbolizing the moon and the circle signifying the sun likely evoke the feminine-masculine couple of Dahomean Vodun deities Mawu-Lisa.[27] Associated with the creation of the world, the couple Mawu-Lisa embodies the division between the world of the living (sun) and the dead (moon), the day and the night, the sky and the earth, and their complementary nature is what devised Dahomey’s political organization, which was divided into the masculine and feminine realms.[28]

By adding the openwork to the blade of the silver kimpaba, I argue, Fon silversmiths transformed the silver kimpaba from La Rochelle into a unique object of power and prestige that engaged central dimensions of Dahomean cosmology by activating Hevioso, Gu, and Mawu-Lisa. Yet, the duality represented by these symbols was not exclusive to Dahomey. It was also part of the cosmology of Loango coast societies and the overall Kongo region, in which shapes of crosses, diamonds, ovals, and crescents signifying the sun and the moon were also featured on pot lids, bimpaba, and later on tombstones of the early twentieth century.[29] Ultimately, through the added openwork, the silver kimpaba started embodying the symbolic duality that characterized the political structures of the kingdoms of both Ngoyo and Dahomey.[30] By incorporating symbols found in the powerful Fon gubasa to the silver kimpaba, the Hountondji artists also created a metanarrative analogous to the one found in Woyo pot lids that featured representations of bimpada, as well as in Fon applique hangings and the Gu iron sculpture that also depict the gubasa.

In addition to the openwork, I argue that the cross (Fig. 11) at the tip of the silver kimpaba’s blade was likely added to the sword after it reached Abomey. The cross is carved at the same location where the Kongo cosmogram (dikenga) was usually cut out in Woyo swords.[31] The cross pre-existed Christianity and was embraced by Christians to symbolize Jesus of Nazareth’s crucifixion. When the Portuguese reached the Loango coast, the Central African populations were already familiar with the Kongo cross (dikenga), which evoked the cycles of life. Yet, no West Central African-made kimpaba available in museums or private collections bears a Latin cross. It is unlikely that the shipowner Daniel Garesché would have wanted to use the silver kimpaba to promote the Christian doctrine to Cabinda’s Mfuka. Like many other shipowners and slave merchants in La Rochelle, he was not a Catholic but a Protestant, and only Catholics embraced liturgical objects like crosses, chalices, Communion cups, and images of saints as instruments of conversion during the era of the Atlantic slave trade.[32] Likewise, Jean Chaslon, the silversmith who created the kimpaba, was a freemason, and Catholics at least in theory were not supposed to join Masonic lodges.

In contrast, carved Greek and Latin crosses are featured in the blades of at least two Fon récades. In French, the term scepter (makpo in Fon language) was referred to as récade from the word recado in Portuguese, meaning message. A royal insignia, the récade was carried by the king and also by the king’s messenger.[33] Hence, the récade’s function shares similarities with the Woyo mbele, which is to some extent the kimpaba’s ancestor and was also carried by the ruler’s messenger. Several récades feature a spiral shape symbolizing dàn, a serpent associated with the name Dahomey (Danxomɛ), meaning in the belly of Dan, which also evoked the king’s transcendental power. The first scepter consists of a wooden stick (Fig. 12) attached to an axe-like iron blade. At the joint of the blade with the wooden stick is a raised metal spiral shape, similar to the ones found in other récades. One extremity of the blade is engraved with a figure representing a pineapple associated with King Agonglo, who was assassinated after bringing two Catholic priests to Dahomey, having promised them he would convert to Catholicism. Carved in the middle of the blade, the cross shape is also reinforced by an engraved contour line. A similar scepter is a récade made of copper and iron (Fig. 13). A copper lion head, similar to the handle of other Woyo kimpaba, connects the iron blade to the iron stick, whose lower extremity is surrounded by a copper ring engraved with fine lines. A horizontal line formed by three small circles and a cross is carved along the iron blade, while a vertical line composed of four small carved circles decorates the blade’s edge.

Considering all these elements, it is possible that, along with the Vodun symbols, Abomey artisans also cut out the Latin cross on the blade of the Mfuka’s kimpaba. After all this, through the hands of La Rochelle’s slave traders and silversmiths, Woyo agents, and Abomey silversmiths, the kimpaba was transformed into a complex cross-cultural power object. As a speaking object of power, the silver kimpaba is the bearer of several messages. The French words praising the Mfuka’s qualities as a righteous man engaged Cabinda’s agents by reinforcing Pukuta’s importance and political prestige. The added openwork with pictograms evoking Vodun deities addressed members of the Dahomey royal court as well as commoners who may have occasionally admired the king bearing the kimpaba during public appearances.

Afterlives of Cross-Cultural Gifts of Prestige

While embodying West African and European elements, the French silver kimpaba examined in this article marks an important moment in the Atlantic slave trade on the Loango coast. Whereas the Mfuka acquired increasing wealth and power, European merchants observed that rivalries between local merchants and rulers increased, especially during the second half of the eighteenth century. This new configuration gave more power to local men who acted as middlemen on behalf of the king in the inhumane commerce. Cabinda’s Mfuka, like his counterparts of Malembo and Loango, were among these intermediaries. Despite having left Cabinda at some point after Pukuta’s death, the silver kimpaba’s legacy remained active on the Loango coast for many decades. Although bimpaba were originally used as prestige objects by a few powerful West Central African individuals, as the slave trade increased in the eighteenth century European traders started offering a growing number of these silver swords to local chiefs. Along with the Atlantic slave trade, the expansion of European colonialism in the region introduced languages such as French, English, and Portuguese, further diversifying the messages conveyed by these swords. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, European agents, particularly the Portuguese, began presenting locally manufactured bimpaba to regional rulers (Fig. 8), with the rulers’ names prominently displayed on them. Likewise, locally made swords displaying the names of their owners emerged during this same period.[34] To some extent, the kimpaba remained the symbol of local clans and families whose political and economic power increasingly declined during Portuguese and French colonization of the Loango coast. Looted at least twice, today the French silver kimpaba also helps us to interrogate the forced migration of persons and things during the era of the Atlantic slave trade and colonialism.

Ana Lucia Araujo is Professor of History at Howard University in Washington, DC

[1] See, for example, Ana Lucia Araujo, “Dahomey, Portugal, and Bahia: King Adandozan and the Atlantic Slave Trade,” Slavery and Abolition 3, no. 1(2012): 1–19, Mariza de Carvalho Soares, “Trocando galanterias: a diplomacia do comércio de escravos, Brasil-Daomé, 1810–1812,” Afro-Ásia, no. 49 (2014): 229–71; Christina Brauner, Kompanien, Könige und caboceers: Interkulturelle Diplomatie an Gold- und Slavenküste im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert (Böhlau Verlag, 2015); Christina Brauner, “Connecting Things: Trading Companies and Diplomatic-Giving on the Gold and Slave Coasts in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” Journal of Early Modern History 20 (2016): 408–28; Mariza de Carvalho Soares, A coleção Adandozan do Museu Nacional: Brasil-Daomé, 1818-2018 (Mauad, 2022); and Gaëlle Beaujean, “Le Cadeau dans les relations diplomatiques du Royaume du Danhomè au XIXe siècle,” Politique africaine 1, no. 165 (2022): 73–94.

[2] See Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Cécile Fromont, “The Taste of Others: Finery, The Slave Trade, and Africa’s Place in the Traffick of Early Modern Things,” in Early Modern Things: Objects and their Histories, 1500–1800, ed. Paula Findlen (Routledge, 2021), 273–94; Roberto Zaugg, “Le crachoir chinois du roi: Marchandises globales, culture de cour et vodun dans les royaumes de Hueda et du Dahomey (XVIIIe– XIXe siècle),” Annales : Histoire, Sciences Sociales 73, no. 1 (2018) : 119–59; and Ana Lucia Araujo, The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, 2024). In the Indian Ocean, see, for example, Nancy Um, Trade & Architecture in An Indian Ocean Port: The Merchant Houses of Mocha (University of Washington Press, 2009); and especially Nancy Um, Shipped But Not Sold: Material Culture and the Social Protocols of Trade During Yemen’s Age of Coffee (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2017).

[3] These goods were typical on the Loango coast. However, they could vary over time and depending on the African region involved. See Stanley B. Alpern, “What Africans Got for Their Slaves: A Master List of European Trade Goods,” History in Africa 22 (1995): 5–43; and David Richardson, “Consuming Goods, Consuming People: Reflections on the Transatlantic Slave Trade,” in The Rise and Demise of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Atlantic World, ed. Kristin Mann and Philip Misevich (Rochester University Press, 2016), 31–63. For the French slave trade on the Loango coast, see Amanda Gregg and Anne Ruderman, “Cross-Cultural Trade and The Slave Ship the Bonne Société: Baskets of Goods, Diverse Sellers, and Time Pressure on the African Coast,” Economic History Working Papers, no. 333 (Department of Economic History, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2021), 1–60. On the Luso-Brazilian slave trade in West Central Africa, see Daniel Domingues da Silva, The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867 (Cambridge University Press, 2017), 122–41; and Mariana P. Candido, “Women’s Material World in Nineteenth-Century Benguela,” in African Women in the Atlantic World: Property, Vulnerability and Mobility, 1660– 1880, ed. Mariana P. Candido and Adam Jones (Boydell and Brewer, 2019), 70–85, as well as Mariana P. Candido, An African Slaving Port and the Atlantic World: Benguela and Its Hinterland (Cambridge University Press, 2013), 173–5. On the Bight of Benin, see Carlos da Silva Jr., “Enslaving Commodities: Tobacco, Gold, Cowry Trade and Trans-Imperial Networks in the Bight of Benin (c. 1690s–c.1790s),” African Economic History 49, no 2 (2021): 1–30; and Ana Lucia Araujo, “Did Rodney Get It Wrong? Europe Underdeveloped Africa, But Enslaved People Were Not Always Purchased with Rubbish,” African Economic History Review 50, no. 2 (2022): 22–32.

[4] For early examples in the West Central African Kingdom of Kongo, see John K. Thornton, “The Regalia of the Kingdom of Kongo, 1491-1895,” in Kings of Africa: Art and Authority in Central Africa, ed. Erna Beumers and Hans-Joachim Koloss (Foundation Kings of Africa, 1992) 57–63; and Fromont, The Art of Conversion.

[5] See Araujo, The Gift, 63–9.

[6] On eighteenth-century silversmiths in France and La Rochelle, see Solange Brault and Yves Bottineau, L’orfèvrerie française du XVIIIe siècle (Presses Universitaires de France, 1959), 18.

[7] On Louis Chaslon, see Archives départementales de la Charente Maritime (hereafter ADCM), January 17, 1761, 3 E 1672 liasse 1, fl. 35; Archives de la Marine à Rochefort (hereafter AMR) 6P6-7, 1775, no. 28, fl. 1v.; AMR, 6P6 30, 1776, no. 25, fl.1; and Araujo, The Gift, 81–2.

[8] Supplément aux Affiches américaines, January 20, 1776, 33; and Supplément aux Affiches américaines, January 27, 1776, 45.

[9] Tristan Arbousse Bastide, Du couteau au sabre : From Knife to Sabre : Armes traditionnelles d’Afrique 2 (Archaeopress, 2008), 79–80.

[10] Karl Edvard Laman, Dictionnaire Kikongo-Français : une étude phonétique décrivant les dialectes les plus importants de la langue dite Kikongo (Librairie Falk Fils, 1936), 255.

[11] Carlos Serrano, “Símbolos do poder nos provérbios e nas representações gráficas Mabaya Manzangu dos Bawoyo de Cabinda, Angola,” Revista do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia (1993): 142.

[12] Mulinda Habi Buganza, “Aux origines du Royaume de Ngoyo,” Civilisations 41, no.1/2 (1993): 172; and Serrano, “Símbolos do poder nos provérbios,” 142.

[13] Padre Joaquim Martins, Sabedoria Cabinda: Símbolos e provérbios (Junta de investigações ultramar, 1968), 200–01.

[14] Louis-Marie-Joseph Ohier de Grandpré, Voyage à la côte occidentale d’Afrique : fait dans les années 1786 et 1787, contenant la description des mœurs, usages, lois, gouvernement et commerce des états du Congo ; suivi d’un voyage au cap de Bonne-Espérance : contenant la description militaire de cette colonie, 2 vols. (Dentu, 1801), 1:204–5.

[15] Zdenka Volavka and Wendy Anne Thomas, Crown and Ritual: The Royal Insignia of Ngoyo (Toronto University Press, 1998), 35.

[16] Martins, Sabedoria Cabinda, 65.

[17] Julien Volper, “Trois cimpaaba d’argent : Échanges afro-européens sur les côtes kongo (XVIIe-XIXe siècles),” Tribal Art magazine XXV-4, no. 101 (2021): 83-95.

[18] Susan Cooksey, Robin Poynor, Hein Vanhee, and Carlee S. Forbes, eds., Kongo Across the Waters (University Press of Florida, 2014), 113.

[19] Martins, Sabedoria Cabinda, 479.

[20] On speaking objects see Jennifer Trimble, “The Zoninus Collar and the Archaelogy of Romany Slavery,” American Journal of Archaeology 120, no. 3 (2016): 444–72.

[21] For details, see Araujo, The Gift, 52–74.

[22] See Grandpré, Voyage à la côte occidentale d’Afrique, vol. 1, 146-147. Later European explorers also reported the preparation of the corpses of local rulers; see Eduard Pechuël-Loesche, Volkskunde von Loango (Stecker and Schroder, 1907), 157.

[23] Grandpré, Voyage à la côte occidentale d’Afrique, vol. 1, 188. I develop this hypothesis in more detail in Araujo, The Gift, 105–6.

[24] See Araujo, The Gift, 103–20.

[25] On these collections see Suzanne Preston Blier, “Europa Mania: Contextualizing the European Other in Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century Dahomey Art,” in Europe Observed: Multiple Gazes in Early Modern Encounters, ed. Kumkum Chaterjee and Clement Hawes (Bucknell University Press, 2008), 237–70; and Gaëlle Beaujean, “Le Cadeau dans les relations diplomatiques du Royaume du Danhomè au XXe siècle,” Politique africaine 1, no. 165 (2022): 73–94.

[26] On Gu, see Suzanne Preston Blier, African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power (University of Chicago Press, 1995), 340. On the sculpture, see Suzanne Preston Blier, “Words About Words About Icons: Iconologology and the Study of African Art,” Art Journal 47, no. 2 (1988): 81.

[27] Beaujean, L’art de la cour d’Abomey, 62.

[28] See Melville J. Herskovits, “Some Aspects of Dahomean Ethnology,” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 5, no. 3 (1932): 286; Bernard Maupoil, La géomancie à l’ancienne Côte des Esclaves (Institut d’Ethnologie, 1988), 71; and Parés, O rei, o pai e a morte, 210.

[29] On these symbols among the Kongo peoples and on the Loango coast see, for example, John H. Weeks, Among the Primitive Bakongo (Seeley, Service and Co. Limited, 1914); 276–86; and James Denbow, “Heart and Soul: Glimpses of Ideology and Cosmology in the Iconography of Tombstones from the Loango Coast of Central Africa,” The Journal of American Folklore 112, no. 445 (1999): 410.

[30] Carlos Serrano briefly explores the similarities of Ngoyo’s and Dahomey’s culture in Os senhores da terra e os homens do mar, 68–70.

[31] On the Kongo cross, see Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: Africa and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (Vintage Books, 1984), 108. On the Kongo cross and its connections with the Christian cross, see Fromont, The Art of Conversion, 80–98.

[32] The definitive work on this dimension is Fromont, The Art of Conversion.

[33] For more on Dahomey’s récades see Alexandre Adandè, Les récades des rois du Dahomey (Institut de l’Afrique Noire, 1962).

[34] Joaquim Martins, Cabindas: história, crença, usos e costumes (Comissão de Turismo da Câmara Municipal de Cabinda, 1972), 105. See also João Baptista Luís, “O comércio do marfim e o poder nos territórios do Kongo, Ngoyo e Loango: 1796–1825” (MA thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, 2016), 56.

Cite this article as: Ana Lucia Araujo, “Between Europe and Africa: A Gift of Prestige in the Era of the Trade in Enslaved Africans,” Journal18, Issue 19 Africa (Spring 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7728.

Licence: CC BY-NCJournal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.