Noémie Etienne

In 1772, Pierre-Antoine Demachy painted the entrance of the Louvre, known as La Grande Colonnade (Fig. 1). Just in front of the Palace, the old buildings, which were being dismantled, and the Cloître Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois are shown in shadow. A large street, which still exists today as the rue de l’Amiral de Coligny, separates the two architectural ensembles. Almost 300 years ago, this street was crossed frequently by Marie-Jacob Godefroid, born Van Merle (1705–1775), a painting restorer working in Paris during the ancien régime. Her husband, Ferdinand-Joseph Godefroid, a native of Lille, had also been a restorer, but after his death in 1741 Marie-Jacob took over his workshop. Having been a member herself of the Académie de Saint-Luc since 1736, she inherited the rights vested in widows of masters and expanded the family shop.[1] She undertook some of her restoration work in the Godefroid family home on the Cloître Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, where she also stored artworks. Their large number—more than one hundred paintings at the time of her death—bears witness to the volume of her work and the success of her career.[2]

Fig. 1. Pierre-Antoine Demachy, Vue de la colonnade du Louvre, 1772. Oil on canvas. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais/Stéphane Maréchelle. Image source: Images d’art, RmnGP, www.images-art.fr.

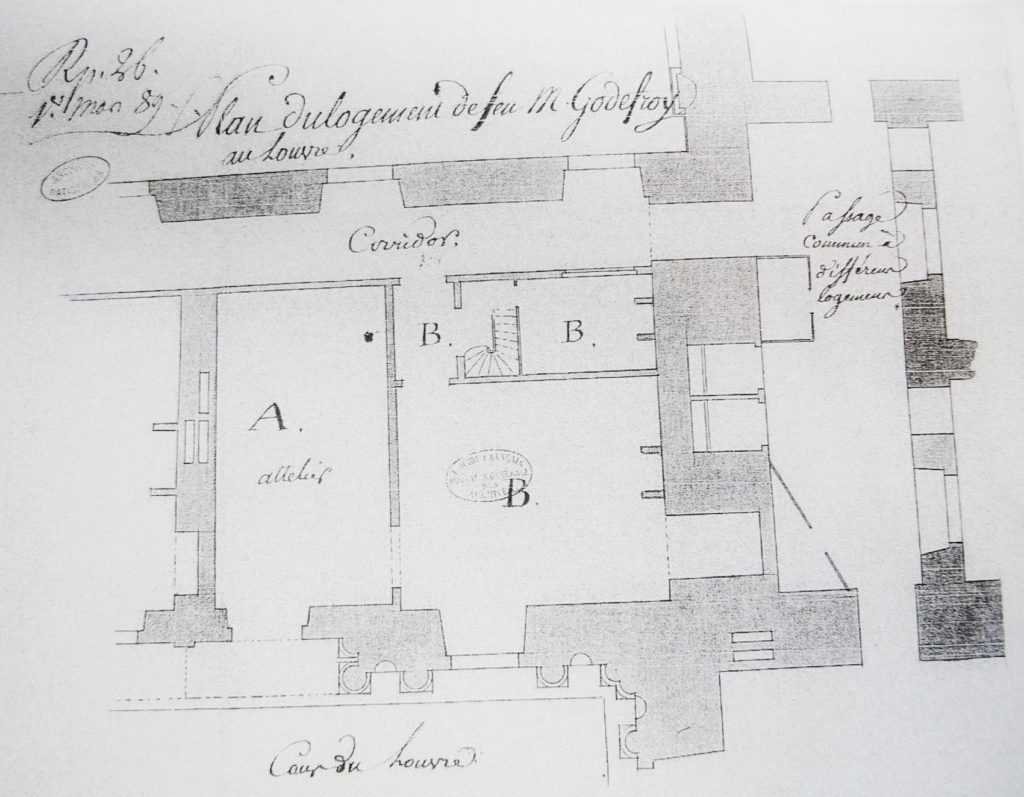

Marie-Jacob might even have crossed this street the night her husband was killed. After enjoying a dinner party near the Louvre, Ferdinand-Joseph died in the Cour Carrée, just a little way beyond the Colonnade, the victim of a tragic murder. In the following years, Marie-Jacob certainly traversed the street multiple times, going from her atelier in the Cloître to her second studio within the Louvre itself. Later, she would cross the street to visit her son, Ferdinand-François Godefroid (1729–1788), also a restorer, who lived and worked in her palace studio, which she had been granted thanks to her position as a restorer of the king’s collection. Initially she was granted some space for a workshop in the Louvre’s Galerie d’Apollon, but in 1763, when that gallery was given over to the Academy, Marie-Jacob obtained a new studio located in the main palace on the second floor of the Colonnade.[3] A plan dated December 17, 1788, executed after the death of Marie-Jacob’s son, offers some sense of these lodgings on the second floor of the eastern wing (Fig. 2). The plan reveals that logement (marked B) and atelier (marked A) were in the very same space, indicating the flexibility and potential circulation between private and professional realms.

Fig. 2. Plan of the lodgings of Joseph Ferdinand-François Godefroid at the Louvre. Archives nationales de France, Paris, AN O1 1674. Photo by the author.

This short essay focuses on the organization of the Godefroids’ working lives. The family provides a fascinating case for examining the economics of a restoration workshop, but Marie-Jacob’s activities as a restorer around the Louvre also sheds light on the intricacies of this artistic milieu during the second half of the eighteenth century. Living near artists from the Académie royale and the Académie de Saint-Luc, as well as suppliers and other restorers, Marie-Jacob was part of a dense network of people, tools, and artworks. Most studies of artisans in the ancien régime have examined professional practices through a strict reading of the guild system, but such an approach does not accommodate the diversity of the actors involved nor acknowledge the importance of everyday encounters forged through domestic proximity. Moreover, focusing on the circulation of restorers between different physical and symbolic spaces sheds light on their mobility. From this perspective, crossing the street separating the Cloître and the Louvre was not only a physical activity done for practical reasons, it also had a symbolic dimension. As we shall see, Marie-Jacob’s studio at the Louvre became an object of negotiation after her death, and the ensuing discussion offers insight into the tensions raised at the Louvre in the last decades of the ancien régime.

The social geography of any professional milieu needs to be reconstructed in order to understand how people and things were connected. To some extent this can be achieved through a careful reading of various contemporary registers that list the names and addresses of the practitioners. Unfortunately painting restorers in early modern Paris were not listed under a specific heading in the trade registers produced at the time. Nor were they part of a single corporation, instead being grouped variously with painters, ébenistes, or marchands-merciers. Unlike painting restorers, repairers of engravings were given their own category in the 1776 Almanach historique et raisonné des architectes, peintres et sculpteurs, but it listed only three of them, as compared to the thirty-four people listed as dealers of paintings and engravings.[4] Meanwhile, under the heading “Objects relating [to] painters of history, portraits, flowers,” the royal tablettes, a publication giving the names and contacts of various professionals, provided the names and addresses of individuals specializing in the repair of such works.[5] Thus it is possible, through a systematic cross-reading of the various tablettes and almanachs, to map the restoration milieu and retrieve some idea of the range of people involved.

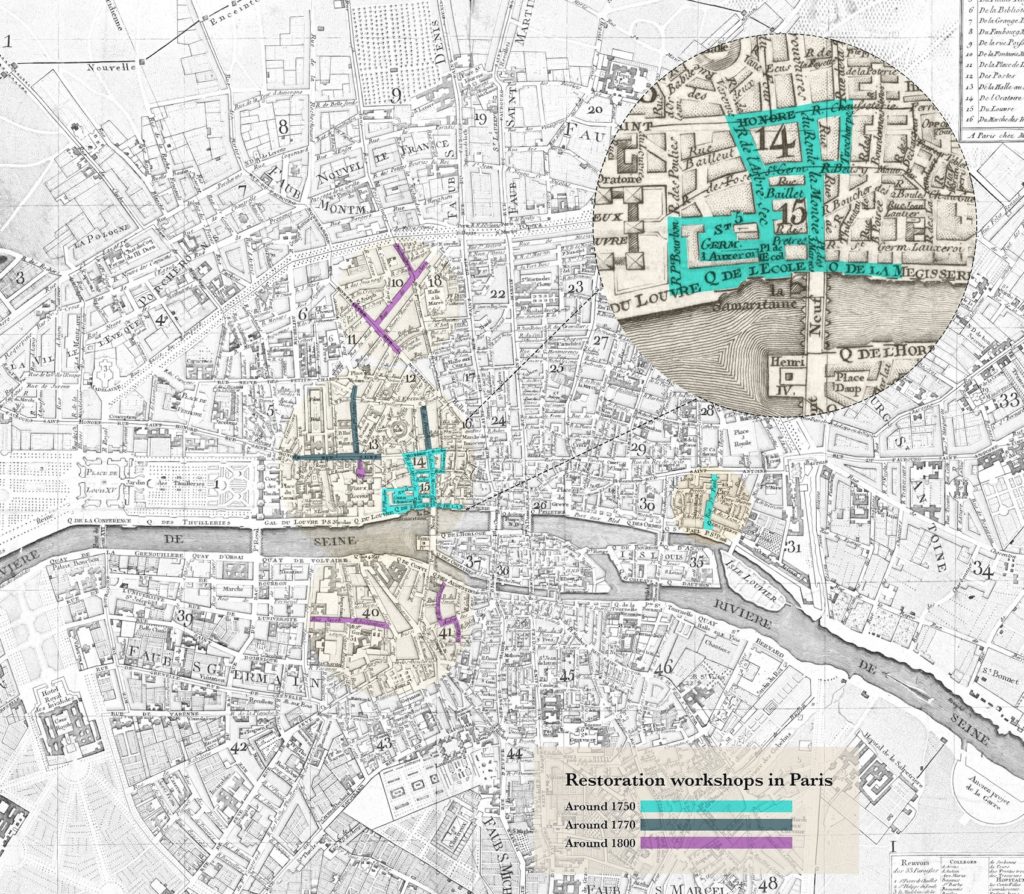

Around 1750, craftsmen, artists, and suppliers involved in restoration were mainly grouped in the Louvre quarter, which housed a dense and concentrated network of dealers’ shops and workshops of painters practicing restoration.[6] The center of this activity was the Cloître Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, located opposite the Louvre Colonnade. This is where Ferdinand-Joseph Godefroid and his wife, Marie-Jacob, resided, as did Emmanuel-Bernard Hooghstoel and his son Jean-Marie, also restorers, before they later moved to 15 rue de la Monnaie. The famous restorer Jean-Louis Hacquin founded his workshop behind this street, at 4 rue du Bourdonnais, and the dealer, expert, and restorer Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun took over his father’s shop and lived nearby on rue de l’Arbre Sec until 1776. Quai de la Mégisserie, which bordered the quarter and ran perpendicular to rue de la Monnaie and rue du Bourdonnais, was also a focus of restoration activity and helped shape this area into a center corresponding approximately to the commercial sector concentrated on the city’s Right Bank (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Map showing main centers of restoration activity in eighteenth-century Paris. The changes reflect an expansion of activity rather than a simple migration as earlier centers of activity were not abandoned during later periods. Base map: Plan de la ville et Faubourg de Paris, divisé en 48 sections, décrété par l’Assemblée Nationale, le 22 Juin 1790, et sanctionné par le roi. Map source: Wikimedia Commons.

The proximity of the different shops and their location in a limited geographic area fostered relationships among the actors. Dealer-restorers entered into alliances with various people to purchase paintings intended for resale. Whether they frequented the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture or the Académie de Saint-Luc, social heterogeneity characterized the circles in which these figures moved. Indeed, we get a sense of this societal de-compartmentalization from the people present at that same dinner in the Louvre attended by Ferdinand-Joseph Godefroid before his death. Among their guests were Michel Vandelvoort, a Belgian sculptor also living at the Cloître Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois; Charles Parrocel, a painter and member of the Académie royale; André-Charles Boulle, son of the famous French ébeniste; and Jérôme-François Chantereau, a painter, engraver, art-dealer, and member of the Académie de Saint-Luc, who was in fact the man responsible for killing his friend, Ferdinand-Joseph, after a fight over the attribution of a painting he wanted to sell (Godefroid maintained that the painting in question was by Carlo Maratta, while Chanterau argued that it was a copy).[7] Ferdinand-Joseph Godefroid was also the friend of Carel van Falens, who served as painter to the Duc d’Orléans and was a member of the Académie Royale since 1726. Despite his royal position and academic status, van Falens ran a painting shop, and he and Ferdinand-Joseph collaborated on the restoration of paintings.

Many painters belonging to the Académie de Saint-Luc worked in the field of restoration. This was true of Mathias Barthélémy Röser, who specialized in work involving the paint layer. Jean-Baptiste Slodtz, another painter to the Duc d’Orléans and the brother of Michel-Ange Slodtz, was both a painter and a restorer,[8] as was Emmanuel-Bernard Hooghstoel.[9] Many restorers based in the Louvre quarter were French, but a fair number of them were from foreign countries with strong restoration traditions, mainly Flanders and Germany (indeed Marie-Jacob’s own family came from the city of Antwerp). Characterized by cultural and social diversity, the restoration world in the Louvre quarter was also underpinned by family and friendship ties. For example, the painter and restorer Hugues-Henri Guillemard worked with Marie-Jacob Godefroid and, like her, resided on the Cloître Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois until 1798. On July 22, 1764, he was present at the marriage of Marie-Jacob’s son, Joseph Ferdinand-François, to Marie-Madeleine Ganneron, the daughter of a locksmith.[10]

The social scope of Marie-Jacob’s clientele was likewise broad. Thanks to the Godefroid family’s long-established royal ties, her most important client was certainly Louis XV, king of France (r. 1715-1774). Ferdinand-Joseph was employed by the Bâtiments du Roi when he died, and, soon after her husband’s death, Marie-Jacob herself became a pensioner of the Bâtiments. Beginning in 1743, she was officially placed in charge of the restoration of royal paintings. At the same time, she continued working with clients from the aristocracy and the clergy. Some of these customers she inherited from her husband. For example, important figures like the writer Louis Petit de Bachaumont had already employed Ferdinand-Joseph to restore their paintings before continuing as clients of Marie-Jacob. Furthermore, her work for the crown put her in touch with high-level officials such as the Marquis de Marigny, directeur-général of the Bâtiments du Roi, who later also became one of her private customers. The intendant of the Menus-Plaisirs, Denis-Pierre-Jean Papillon de la Ferté, hired her to restore paintings in his cabinet; and the Duc de Choiseul and Jean Nicolas Boullongne, contrôleur of finances and a lay member of the Académie Royale, were also among her clients.

People as well as tools had significant mobility within the workspaces themselves. The Godefroid family shop on the Cloître occupied part of the ground floor of the house, while the restoration workshop was located in one of the bedrooms. So the workshop, situated in the domestic area, was separated from the commercial space below. However, this separation inside the house did not prevent circulation between the different spaces. Indeed, the physical organization of the studio actually encouraged movement. Marie-Jacob’s workshop comprised employees and support staff who laboured on an ad hoc basis to perform specific tasks. She partnered with several colleagues, including the dealer François-Louis Colins and the painter and restorer Hugues-Henri Guillemard, who lived nearby. The two men were assigned to pictorial work, while Marie-Jacob focused on cleaning interventions and restoring the backs of paintings. This division of labor was not, however, accompanied by a separation in the workshop space. The estate inventory taken after Marie-Jacob’s death describes, in the same room, a large easel for retouching the paint layer as well as marble tables for relining and transfers.[11]

Tools and objects also circulated between the Louvre and the Cloître, suggesting that the same material was used for the restoration of the king’s collection as for the collections of private patrons. Various tools were found in the Louvre studio when the son of Marie-Jacob died. Some may have been used for restoration, such as “three large oak trestles, one double and one single ladder, and three old easels, a flight of six steps made of light carpentry,” and some small “jars of ultramarine”.[12] The variety of tools stored in the Louvre workshop (trestles, ladders, brushes, colors, etc.) also bears witness to Joseph Ferdinand-François’s versatility, for he performed both the relining and retouching of the paint layer. Many of these tools might have been transferred from Marie-Jacob to her son, who continued the familial organization of restoration work.

In fact, Marie-Jacob had probably collaborated with her son since he was a very young man. The employment of women and children was crucial in the restoration milieu at the time, even if their work and their names are often not recorded in archival sources. Marie-Jacob herself, as with many other women in the artisan milieu, is largely invisible in the archives until her husband passes away. However, as soon as she was in charge, she demonstrated all the economic and technical skills necessary for the job, suggesting that she had actually been performing these skills for a long time. Similarly, the work of Marie-Jacob’s son is not identifiable until after the death of his father in 1766 (Joseph Ferdinand-François was already 37 at that point) and appears even more frequently after his mother’s death in 1775.

The versatility I have traced in the restoration milieu should not conceal – and might perhaps even explain – the fact that the social status of restorers was under considerable discussion at the time. Marie-Jacob’s son certainly sought social elevation, seeking to define himself as an artist while still practicing restoration work. Joseph Ferdinand-François had in fact been a student of the painter Charles-Joseph Natoire, and Marie-Jacob (who had won the favor of Charles-Nicolas Cochin) successfully lobbied the two men for her son to spend time at the Académie de France in Rome, where Natoire was the director between 1751 and 1777.[13] In Rome, Joseph Ferdinand-François made copies of old masters and pursued an academic artistic training, but he also acquired valuable skills for the restoration work he later performed.[14] Certainly more educated than his mother, Joseph Ferdinand-François also wrote and published booklets, authoring one about the paintings of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in which he commented on their recent restoration and demonstrated his art historical knowledge.[15]

Despite Joseph Ferdinand-François’s attempts at social elevation, the Godefroid family would eventually lose their Louvre studio. As for all craftsmen and craftswomen in the last decades of the century, being able to stay in the palace became a contested issue. By the time Joseph Ferdinand-François Godefroid died in 1788, the status of his profession had been relegated to an inferior position, and restorers were no longer allowed to live in the Louvre. An anecdote concerning Marie-Jacob’s workshop captures this change. In 1788, the wife of Joseph Ferdinand-François applied to retain possession of the workshop for herself and her children, both of whom were studying painting. In his capacity as director of the Bâtiments du Roi, the Comte d’Angiviller refused to grant her request, since the younger Godefroid had not been a member of the Académie or pensioned by the Bâtiments.[16] This refusal was part of d’Angiviller’s desire to distinguish artisans clearly from artists and to limit lodgings at the Louvre to the latter only. Interestingly enough, a local painter called Cuvillier seized the opportunity to compose a disparaging history of the Godefroid family. In a letter to d’Angiviller, he wrote:

The Godefroid family has been restoring the king’s paintings for 60 years; the lodgings of the departed Mr. Godefroid were formerly his restoration workshop, and it was his father and his mother who performed the work and paid for the arrangements necessary to convert it into lodgings. Mr. Godefroid’s mother ultimately enjoyed a pension of 200 livres as the widow of a restorer of the king’s paintings and a restorer herself. It should be noted that the elder Mr. Godefroid was not essentially on a footing very different from the deceased gentleman. He was an art dealer who was found to have sufficient ability, and who was employed, not as an appointee for this task, but on a jobbing basis. The younger Mr. Godefroid was not differently used, except that I believe he was not the only one. [17]

Comparing Joseph Ferdinand-François to his father as little more than a clever dealer, Cuvillier completed his downplaying of the Godefroid family business by noting that they enjoyed no fixed appointment and were paid by the job. Thus, the younger Godefroid was merely “a restoration entrepreneur paid so much a foot for his work.”[18] Meanwhile Marie-Jacob, although without doubt the main protagonist of this family story, was barely mentioned.

This discussion of the status of restoration echoed the debates taking place in art institutions during the second half of the century, which pitted the Académie Royale against the guild’s Académie de Saint-Luc.[19] While restoration was not necessarily linked to the painters’ guild, terms such as “entrepreneur” that were used to describe guild members were also those used to characterize restorers around 1770, even those who frequented the Académie Royale de Peinture, like Joseph Ferdinand-François. The use of this terminology clearly placed the restoration practice in the artisanal world, patently distinguishing it from the field of fine arts, in a movement that began with the directorship of the Marquis de Marigny and was confirmed under the directorship of the Comte d’Angiviller. After the Revolution, the opening of the Musée Central des Arts in 1793 represented a decisive step in the professionalization and definition of restoration.

The historian Simona Cerutti has recently made a claim for the necessity of writing “history from below.” Such an approach means at least two separate yet connected things: first, it encourages the study of people who engaged in more modest activities, such as, in our case, painting restorers, as opposed to more frequently studied protagonists such as painters working in royal institutions. Second, it proposes the use of more basic, technical, or even administrative archival sources such as inventaires après décès, technical treaties, restoration bills, etc. From this perspective, “below” is both a method and a place from which to observe and reconsider our objects of study. Taking such a scholarly approach to investigate a building like the Louvre has enabled a repopulation of this unique Parisian quartier, while also revealing the circulation of those people and their goods throughout the neighborhood. In doing so, the palace appears not as an impermeable fortress in the middle of the city, but as a place of circulation, transition, and interaction. Seen from below, the Louvre looks as it does in Demachy’s depiction (Fig. 1): a building busy with people all around, entangled in social tensions, whose boundaries were challenged, colonized by the little stalls that were progressively dismantled after 1757 following the order of the Bâtiments du Roi. Furthermore, this approach also reveals the multiplicity of the people working and living in the various buildings, and walking through the streets of the Louvre Quarter. Finally, as the example of Marie-Jacob Godefroid shows, discovering how people interacted in workspaces brings to light those frequently invisible actors, such as women and children, laboring in the shadows of the archive’s more dominant figures. Writing art history from below thus becomes a productive way of repopulating the eighteenth-century “art world,” as Howard Becker conceptualizes it[20], to encounter the myriad people interacting with art in the early modern city.

Noémie Etienne is SNSF Professor of Art History at the University of Bern, Switzerland

[1] S. Juratic and N. Pellegrin, “Femmes, villes et travail en France dans la deuxième moitié du XVIIIe siècle: Quelques questions,” Histoire, Économie, Société 3 (1994), 477-500; D. M. Hafter, Women at Work in Preindustrial France (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007). This note is based on my book, La restauration des peintures à Paris, 1750-1815 (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2012), forthcoming in English as The Restoration of Paintings in Paris, 1750-1815 (Los Angeles: Getty Publications), translated by Sharon Grevet.

[2] Archives Nationales de France (hereafter AN), MC, XXIV, 885; December 6, 1775: estate inventory of Marie-Jacob Van Merle, widow Godefroid.

[3] “Il y a une place dans la Galerie d’Apollon qui me paraîtrait convenir au travail de M. Colins et de Madame Godefroy [sic], c’est l’endroit qui sert de dépôt à M. Bailly pour mettre toutes les copies, les mauvais tableaux et les vieilles bordures. Comme cet endroit est fermé et éclairé par deux grandes croisées je crois qu’il serait difficile de trouver rien de plus convenable : l’ouvrage se ferait sous les yeux de M. Van Loo, et il n’y aurait autre chose à faire selon moi qu’à ordonner à M. Bailly de chercher un réduis au Luxembourg pour y placer toutes ses vieilleries,” AN, O1 1907 B-83.

[4] Almanach historique et raisonné des architectes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs et ciseleurs (Paris: 1776), 213.

[5] M. Roze de Chantoiseau, Premier trimestre des tablettes royales de renommées, d’adresse perpétuelle et d’indication des négociants, artistes célèbres et fabricants des 6 corps (Paris: Chez Desnos, Veuve Duchêne, 1775), 58.

[6] The following information stems from a systematic reading of various almanachs published in Paris between 1750 and 1800, such as Almanach historique et raisonné des architectes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs et ciseleurs, Almanach du Dauphin ou Tableau du vrai mérite des artistes célèbres du royaume, et indications générales des principaux négociants, artistes et fabricants des six corps des arts et métier de la ville et faubourg de Paris et autre ville du royaume, or Almanach du commerce.

[7] J. Guiffrey, Scellés et inventaires d’artistes (Paris: Charavay frères, 1883), vol. 1, 394–417.

[8] F. Marandet, “Pierre Remy (1715-97): the Parisian art market in the mid-eighteenth century,” Apollo 158 (August 2003), 34.

[9] AN, ET LIV 995, October 16, 1781: Estate inventory of Madame Hoogstoel.

[10] AN, MC, XCIV 322, July 1764: Marriage contract between Marie-Madeleine Ganneron and François-Ferdinand Joseph Godefroid.

[11] Paris, AN, MC, XXIV, 885; December 6, 1775: Estate inventory of Marie-Jacob Van Merle, widow Godefroid.

[12] Paris, AN, MC, XXIV, 969 1788: Estate inventory of Joseph François-Ferdinand Godefroid.

[13] A. Montaiglon and J. Guiffrey, eds., Correspondance des directeurs de l’Académie de France à Rome avec les surintendants des Bâtiments, published after manuscripts from the Archives Nationales (Paris: Charavay frères, Librairie de la société de l’histoire de l’art français, 1900), original written July 29, 1753, vol. 10 (Years 1742–1753), 458.

[14] Vandières to Natoire, August 29, 1754, in Montaiglon and Guiffrey, Correspondance des directeurs de l’Académie de France à Rome, vol. 11 (Years 1754–1763), (Paris: 1901), 47.

[15] [J.-F. Godefroid], Description historique des tableaux de l’église de Paris (Paris: Veuve Hérissant, 1781). His daughter, Marie-Eléonore Godefroid (a granddaughter of Marie-Jacob), ultimately became a painter.

[16] Letter from Cuvillier to d’Angiviller, Paris, AN, O1 1920.2-119.

[17] “La famille Godefroid est depuis 60 ans employée à la restauration des tableaux du Roi ; le logement du feu Sieur Godefroid était jadis l’atelier de restauration et il est l’ouvrage de son père et de sa mère qui en ont fait tous les frais des arrangements nécessaires pour en former logement. La mère du Sieur Godefroid jouissait enfin d’une pension de 200 livres comme veuve d’un restaurateur de Tableaux du roi et Restauratrice elle-même. Il est à remarquer que le Sieur Godefroid père n’était pas au fond sur un pied fort différent que ne l’était le Sieur mort. C’était un marchand de tableau dans lequel on avait trouvé la capacité suffisante, et que l’on employait non comme appointé pour cette besogne ; mais par mémoires d’ouvrages. Le Sieur Godefroid fils n’était pas autrement employé, si ce n’est que je crois qu’il n’était pas seul.” Letter from Cuvillier to d’Angiviller, Paris, AN, O1 1920.2-119.

[18] Letter from Cuvillier to d’Angiviller, Paris, AN, O1 1920.2-112.

[19] For the historical and legal context, see Katie Scott, “Hierarchy, Liberty and Order: Languages of Art and Institutional Conflict in Paris (1766–1776),” Oxford Art Journal 12:2 (1989), 59-70; Charlotte Guichard, “Arts libéraux et arts libres à Paris au 18e siècle: peintres et sculpteurs entre corporation et Académie royale,” Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine 49:3 (2002/3), 60.

[20] “All artistic work, like all human activity, involves the joint activity of a number, often a large number of people. Through their cooperation, the art work we eventually see or hear comes to be and continues to be The work always shows signs of that cooperation. The forms of cooperation may be ephemeral, but often become more or less routine, producing patterns of collective activity we can call an art world.” Howard Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982), 1.

Cite this article as: Noémie Etienne, “A Family Business: Picture Restorers in the Louvre Quarter,” Journal18, Issue 2 Louvre Local (Fall 2016), https://www.journal18.org/830. DOI: 10.30610/2.2016.2

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.