Ushma Thakrar

Shortly after being elected to office in a landslide victory in 2014, Narendra Modi, India’s then and current prime minister, appeared on Dashashwamedh Ghat on the banks of the Ganges River in Varanasi, from where he took part in a prayer for the Hindu river deity, Ganga. In his widely publicized address to spectators following the prayer, Modi evoked not the Ganges as a river, but “Ganga Maa” (literally “Mother Ganges”)[1] as the entity that “called” him to office and that he sought to serve while in office, placing Hindu sacred geography at the center of his vision for leading the country.[2] In Modi’s reference to Ganga as mother [maa], he conjured the Hindu deity, worshipped for her capacity to spiritually and materially cleanse. In this speech, Modi drew on the river, which is now heavily polluted, to demonstrate a degradation of Hindu values in the country and, relatedly, to posit that cleaning, not just of the river but the entire country, is key to restoring Hinduism’s dominance in India. This ethos has been organized under one of the Modi government’s first flagship campaigns, Swachh Barat Abhiyan [Clean India Movement].[3] The movement draws together concerns for bodily health and personal hygiene with environmental and ecological conservation and rehabilitation under a single umbrella.[4] In this program, various forms of cleaning, from regular bathing to the provision of modern toilets and water treatment, are all equally required to restore a past when Hindu spiritual purity thrived.

As Gaston Bachelard has theorized, the materiality of water and the socio-cultural imaginaries that are organized around it are distinct, though they converge on and are understood as referring to the same “stuff.”[5] Sugata Ray and Venugopal Maddipati note that it is the very materiality of water—its free-flowing and uncontainable nature—that make it matter that can be made to take on the shape of any ideology. They remind us that although this quality of water allows it to be projected upon, it is also this same quality that makes it unfixable: “inconsistent epistemologies of water […] deracinate any attempt to contain it within singular ideological frameworks, nationalist or otherwise.”[6] This article traces the water that has been codified as the Ganges River through conflicting imaginaries and ideologies during the late eighteenth century to gain insight into the function of Narendra Modi’s efforts to tightly contain and control the symbolism of the now polluted river within a Hindu sociopolitical sphere. Taking the related schisms between Ganga and the Ganges and between water and river as sites of investigation, it charts the development of Varanasi in relation to the Ganges River alongside changing attitudes toward the secular and religious cleansing properties of water. These histories are brought together to contextualize the socio-political ambitions of the current project of restoring the Ganges River to a state of “cleanliness” in a long environmental history of culturally-produced water.

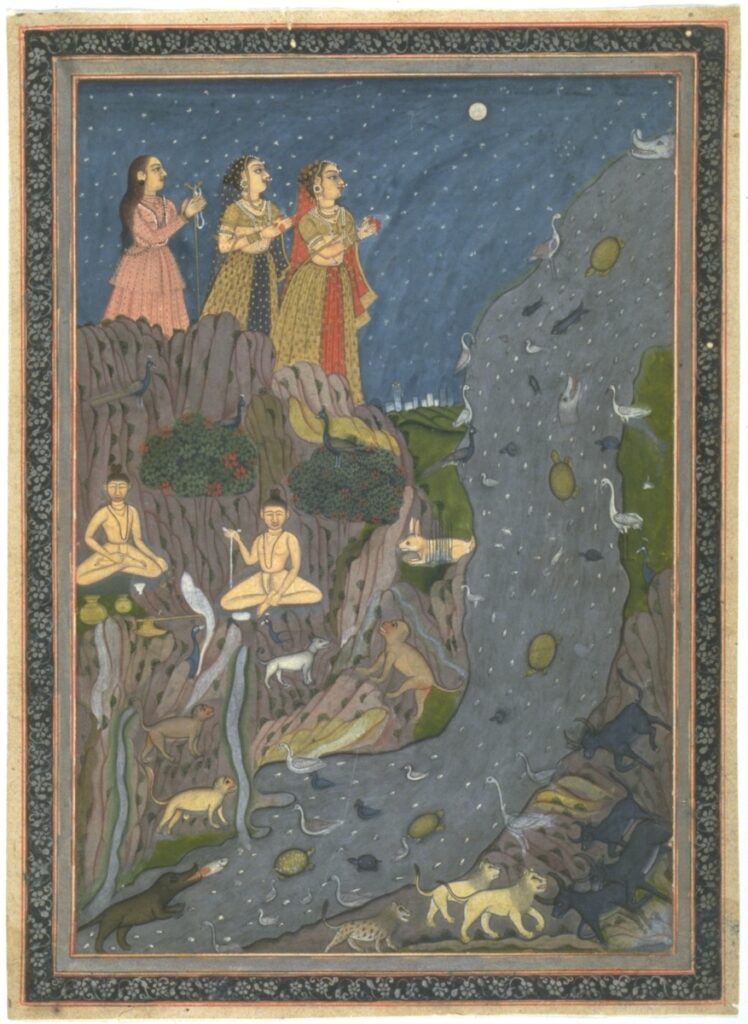

The Ganges River, which intersects with and is made visible in the city of Varanasi, has been shaped by and through various intersecting histories of material and spiritual cleansing. Even today, much continues to be made of the Ganges River (and Varanasi as an extension of it) as central to Hindu socioreligious geography. Despite its irrefutably polluted state,[7] the river’s association with cleanliness remains particularly strong among Hindus in India and the diaspora due to its prominent space in Hindu cosmology. The Gangavartha [The Story of Ganga] tells the tale of Ganga, the Hindu goddess who performs pavitra [simultaneous bodily and spiritual purification] and grants moksha [liberation], descending onto Earth to redeem the spirits of a pious king’s ancestors. In order to prevent the force of her descent from the celestial realm to Earth from causing mass ruin, Shiva, the god of destruction, undoes his braid and lets his hair down to allow Ganga to ride down his celestial hair onto the earth’s surface, softening the impact of her fall. (Fig. 1) The Ganga’s movement emerges first in a steady flow and then splinters along loose tendrils of hair. This eco-religious story unfolds across two actual geographic planes. The more prominent presence of Ganga is in the form of the lock of Shiva’s hair that guides Ganga along the Himalayan mountain range, along the topography of northern India to form the Ganges River and numerous smaller rivers and estuaries. The less discussed form of Ganga is in the movement downward from the skies as rain. The Gangavartha layers onto the map of South Asia and adds a layer of meaning to the annual monsoon, ascribing to both the geography and the yearly environmental event the powers of purification.

Although the interpretation of the Ganges River through the Gangavartha has been particularly far-reaching since Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party came into political power, it is just one of the many narratives that give form to the river. During the eighteenth century, the meaning and materiality of the river was constructed in radically different ways across successive periods of Mughal rule, Hindu dynasties coming into power, and later colonial intervention. Although each change in power saw a reorganization of the symbolic meaning of the Ganges River, the successions of various political, economic, and religious powers in the city throughout the eighteenth century were not neat and often saw collaboration between distinct regimes and divergent interests. Over the course of these changes, the Ganges River remained an important symbol, though it was deployed and imbued with different meanings by each regime as part of their respective agendas of bodily, urban, and spiritual hygiene. This fact has contributed to the kaleidoscopic lens through which the Ganges River must be read today.

The Riverfront as Political Canvas

Narratives of the Ganges River as the Hindu river and Varanasi as the Hindu city par excellence rely on the idea that they have held these titles since time immemorial. However, Madhuri Desai reminds us that “many aspects of the spatial environment of contemporary [Varanasi] were initiated and realized over the course of the eighteenth century, overlaid on the city’s preexisting Mughal framework.”[8] The rulers of the Mughal Empire (1526–1858) and the Mughal nobility were important actors in giving form to the image of the city held by those who see it as the original Hindu city. In 1738, as part of a larger devolution of power to regional rulers, Balwant Singh of the Narayan dynasty, a “feudal subordinate” of the Nawabs of Awadh, became “Raja of Banaras.” Under Singh, there was a resurgence of political influence for several regional Hindu family dynasties, many of whom had continued to build their generational fortunes throughout the period of Mughal rule. As Desai writes, Singh “sponsored religious activities in the city and patronized Brahmins and their literary activities at his court.” [9] In Varanasi, members of the Maratha dynasty also exerted their influence to shape the city. The Marathas were among the most active builders in the city in the eighteenth century until the East India Company transformed from a mercantile body to a colonizing one and took control of Varanasi in 1781.

Madhuri Desai notes that Varanasi’s riverfront was developed as a “political canvas” manifest in architecture in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which was a period of Mughal rule.[10] For the Mughals, water, particularly as it related to Varanasi’s edge, was a prominent material concern. Starting with Emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605), generations of Mughal emperors and elites developed the Varanasi riverfront with private and public buildings and infrastructure to mark the landscape with shows of soft power, but also for garden irrigation, cooling, and daily use.[11] Mughal-era architecture along the waterfront, built on the traces of the previous city, largely took the form of not only mosques but also forts, tombs, temples, and palatial residences. Desai explains that, “As the Mughal state engaged diverse religious and ethnic communities and regional cultures, administrators strove to find models that could accommodate difference within an overarching yet flexible imperial structure of land ownership, taxation, and symbolic authority.”[12] Building projects were important in creating a “cosmopolitan” urbanism and symbolized strength and power not only as overt shows of wealth, opulence, and solidity, but also in their designs, which were intended to be “observed and approached from a boat that glided along the river,”[13] to make the visitor feel diminutive in their presence.

Desai explains that these architectural forms not only engaged with the waterscape as a mode of approach but also frequently had channels of flowing water running through the gardens and structures.[14] As in other monumental Mughal buildings of the era on the subcontinent, which were often commissioned to include “gardens, water pavilions, and reservoirs to both conserve and manage water but also to embellish imperial land,” these structures served as localized reminders of the agricultural canal irrigation that the empire innovated and established across much of South Asia.[15] In the Varanasi riverfront mosques and palatial structures, water channels likely used gravity to move rainwater collected in central water tanks through a series of basins or fountains and across riverfront terraces to eventually drain it into the Ganges River basin.

The Eighteenth-Century Invention of Ritual

This collecting and harnessing of rainwater in Varanasi was not solely an occupation of the Mughal emperors. That it was a recurring period of rainfall, and not a particular earth-bound point source, that brought Ganga meant that rainwater too materialized as a cleansing liquid to the city that was reveredin the post-Mughal Hindu city building of Varanasi. The 1730s saw a definite uptick in rainwater reservoirs in the city during the Mughal rule’s gradual decline and the ascendency of the Maratha confederacy. With the support of the emergent Hindu aristocracy across India, this “loose federation” of Maratha chiefs focused their energies to gain control over and influence in principal Hindu pilgrimage centres, of which Varanasi was (and continues to be) a primary one.[16] As Desai notes, their efforts were not always successful: “politics and religion, however, did not necessarily align either perfectly or conveniently, and Maratha efforts were often stymied by other Hindu factions.”[17] Upon gaining control over many of these major religious nodes across India, the Marathas sought to focus on revitalizing and reasserting Hindu religious sites and rituals on the fabric of Indian cities, not least of all in Varanasi.[18] In the revivalist vision of Varanasi as a Hindu city under the Marathas, they specifically invoked the spiritual symbolism of the rainfall as Ganga as its concentration in the Ganges River basin.

During their time of strong architectural patronage, the Marathas and other elites built a host of water infrastructures that allowed access to the Ganges River and collected the monsoon’s waters, seeking to harness its spiritual powers and draw pilgrims seeking moksha to the city. The revitalization and reconstruction of the ghats, the riverfront terraces that step down into the Ganges River along the Western edge of Varanasi, is the most known and visible of these eighteenth-century interventions. The ghats created important points of access to the river for both religious bathing and secular cleaning, particularly in the forms of bathing and laundry. Though many of Varanasi’s ghats already had a place in Hindu life and secular mercantile commerce throughout the period of Mughal rule, in the 1730s the elite patrons of the eighteenth century, including the Marathas, made significant investments in these sites to “foster and perpetuate the city’s Brahmin-centred ritual life.”[19] Desai credits the Nawab of Awadh’s provincial administrator, Meer Rustam Ali, with some of these innovations: “It was Meer Rustam Ali’s patronage for built forms and celebrations rather than the early Brahmin-centric, ritually correct yet materially sparse interventions of the Marathas that ultimately molded the material and social forms of a socioreligious sphere and its anchoring architecture.”[20] The Brahmin scholar and advisor to the Maratha Peshwa, Narayan Dikshit Patankar, was, however, responsible for the eighteenth-century transformation of the Manikarnika ghat into perhaps the pre-eminent Hindu funerary site.[21] It is there that the bodies of the deceased are submerged into the Ganges River for purification before being cremated and from where the deceased’s ashes are returned to the river for further cleansing en route to the afterlife. Although today this Hindu relation to the Ganges River in death has been naturalized as a tenet of a religious life, it is in actuality a relatively new invention that was intended to establish and maintain the stronghold of Hinduism in Varanasi.

The re-invention of Varanasi in the eighteenth century was not through the creation of water infrastructures per se, due to the fact that the majority of infrastructural projects that became important had previously been constructed and maintained to varying degrees, though under different terms, during the period of Mughal rule. Rather than strictly a building project, the eighteenth-century reconstruction of Varanasi involved rituals to be performed in/on/around water infrastructures, which as a result became inscribed by the spiritual dimensions of the goddess Ganga in these infrastructures. Co-produced with local Brahmins whom, in exchange for their endorsements, local rulers and elites would patronize,[22] the eighteenth century involved changing the tenor of religious activity in the Ganges River: from making offerings to the goddess to rituals that allowed for spiritual cleansing of the devotee’s body and self and set the stage for the colonial Hinduization of the city.

City as Catchment

Although the boundaries of the river basin were in fact porous, we are reminded that it is not the Ganges River that exclusively holds purifying powers, but all the water that made up the monsoon’s rainfall that is believed to be a cleansing manifestation of Ganga. Urban water collection systems and associated rituals sponsored by governing and elite bodies abounded across Varanasi. Among these urban water collection systems were, perhaps most notably, temple tanks—rectangular stepwells of varying scales that would most commonly be found directly adjacent to temples or havelis [mansions] and that were built in the eighteenth century, often atop or in the spolia of the earlier Mughal water systems. Stepwells, ponds, pools, and municipal- and domestic-scale reservoirs all positioned the city as an aqueous geography whose water would naturally filter through the ground and drain into the Ganges River basin and would be replenished with seasonal cycles of monsoon. Prior to British interventions in the city, the entirety of Varanasi was historically a catchment of the Ganges River and the site of innumerable traditional water holding systems.[23] Like the Ganges River, these containers of rainwater were understood to share the clouds that released Ganga materialized in the monsoon as their source.[24] These water bodies were all held as sacred and were themselves places of worship and performance of religious rituals.

It is on this basis that architectural historian Dilip da Cunha asks if locals actually saw the Ganges as a river, or simply as “rain held in a multitude of ways,” which includes the full scope of manmade holders of water but also “earth, air, flora and fauna, and even the sea.”[25] Rain was understood as a harbinger of life that was widely dispersed and by no means limited to the constructions designed to contain it. It was not just the Ganges River but the aqueous terrain of the entire city area that had sacred resonance for Hindu locals and pilgrims. Mahesh Gogate explains that nearly every water reservoir in Varanasi is assigned to a Hindu god or goddess.[26] As a result, Hindu religious life in relation to water in Varanasi was not simply concentrated around the Ganges River but dispersed throughout the entirety of the urban fabric and along accessible collection points for Ganga’s cyclical deposits of water in the city. Ritual bathing and offerings to the deity Ganga were not limited to the banks of the Ganges River. The river’s far-extending route and the monsoon’s cross-country deposits allowed the sacredness of Ganga to be found and felt beyond the Ganges River and Varanasi to all the waters of the subcontinent by devout Hindus.[27]

The construction of Hindu Varanasi was a project of producing the popular understanding that not just these bodies of water but the entire catchment of the Ganges River had cleansing properties.[28] Though the catchment was once a naturally occurring feature of the area, it became caught in the crosshairs of religious, political, and economic authority and symbolism of the city of Varanasi. The eighteenth-century rebuilding of the city made it an infrastructural and architectural catchment that held and made rainwater ritually productive before it was allowed to drain and filter through the naturally sloped earth into the Ganges River basin.

Though harnessed, water could not be described as entirely tamed in eighteenth-century Varanasi. Throughout this period, the city and its infrastructure were largely designed based on ever-changing levels of hydration. The presence of abundant, free-flowing, and uncontainable water bears resonance with early Indic narratives which describe the “submersion of land beneath the waters of a universal ocean.”[29] This unfixability of water and the hydrologic cycle contributed to the element’s reading as an otherworldly force in Hindu cosmology. By contrast, when colonial regimes established themselves in the city, conquering and controlling Varanasi’s waters according to British sensibilities became a primary mode of city building.

Naturalizing Water Rituals

Although the most substantial colonial transformations to the city that enacted and acted upon the binary ecological model that saw land and water as separate, took place following the establishment of the British Raj in 1858, the East India Company had laid the groundwork for these interventions beginning in the late-seventeenth century. In The Invention of Rivers, Dilip da Cunha traces the colonial creation of the Ganges River as a contained river rather than a momentary concentration of wetness.[30] The author describes an early colonial misinterpretation of Ganga’s connection to the Hindu sacred landscape of Varanasi, noting that the anglicized naming of the river “Ganges” was likely based on a misunderstanding of the local attribution of the rainfall as an earthly embodiment of the goddess Ganga and applying the naming convention to the river exclusively.[31] In da Cunha’s account, this separation of the river from its cloud-based water source, as well as the rain that shares the same source, is an interruption of a naturally occurring hydrologic cycle.[32] The invention and reproduction of this separation was a massive undertaking which spanned cartographic and artistic representations, linguistic traditions and naming practices, and infrastructural projects, all of which have effectively reduced an ecosystem that da Cunha describes as one of pervasive wetness into a binary of dry land and wet water.[33]

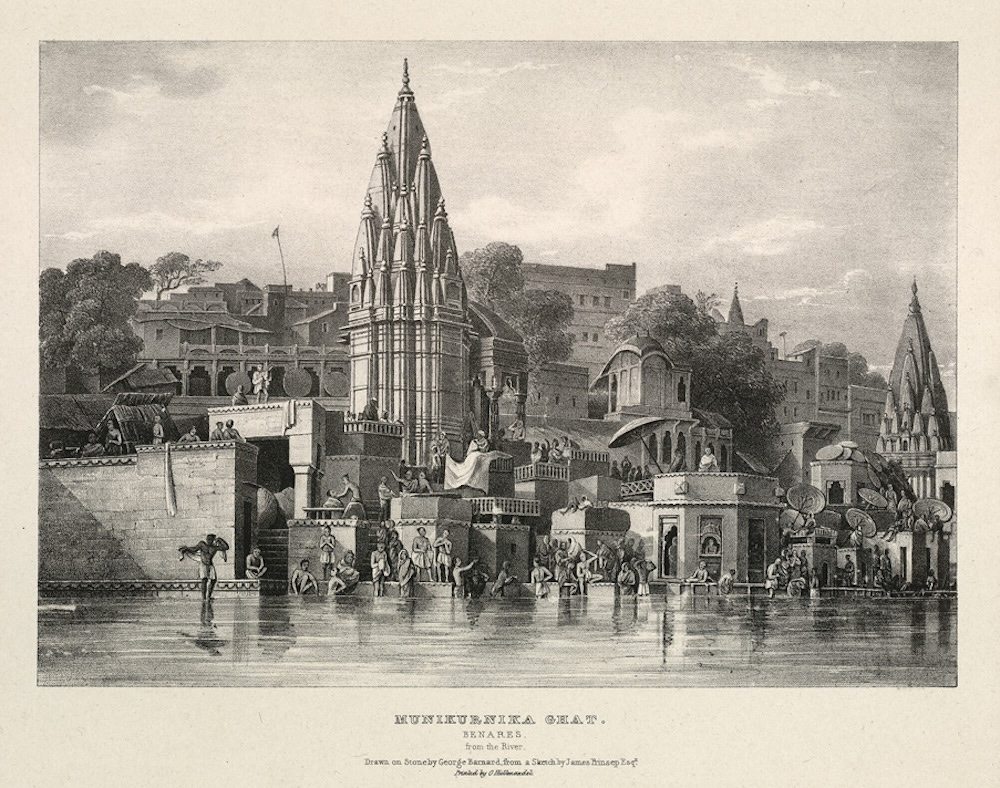

Bernard S. Cohn describes how Warren Hastings (1732–1818), the first British Governor General of India, supported ruling the country according to the customs of its people and invested in a project of surveying and documenting the landscape and its cultural production.[34] As part of this project, Hastings commissioned and patronized several British artists, tasking them with producing realistic renderings of the country. The resulting pieces were aesthetic interpretations of the country made in a picturesque mode. Madhuri Desai notes that although visiting British artists portrayed Mughal-era architecture in a state of decay, artists like William Hodges depicted Varanasi as “the epitome of an authentic, pure, and unspoiled Hindu city.”[35] When Hodges and his contemporaries were painting at the end of the eighteenth century, they made an effort to see an untouched, ancient Hindu city built along a sacred Hindu water body within a complete admixture of Mughal- and Maratha-sponsored architecture and urbanism. Not just the city form but its life was also often depicted as based in Hindu rituals. While Hindu depictions of the Ganges River rarely showed ritual bathing, colonial imagery frequently showed groups of ritual bathers and funerary processions, naturalizing emergent Maratha-sponsored, water-based ritual inventions as part of the city’s ancient history (Figs. 2 and 3).[36]

Severing Ganga and the Ganges

Upon his arrival in Varanasi in the 1820s, James Prinsep (1799–1840) also took up drawing and surveying the city. Unlike earlier British artists who focused on the picturesque qualities of the country, Prinsep recognized Varanasi’s riverfront as the city’s façade, behind which lay the rest of the city: a tangle of “dirty, unwholesome, and confined streets.”[37] In dividing the city into waterfront façade and all the rest of its urban fabric, Prinsep also reformulated the local engagement with the Ganges River from the riverfront ghats: “it is a luxury for [the local Hindu] to sit upon the open steps and taste the fresh air of the river […] the inhabitants of Benares are justly proud of the beauty and spaciousness of the accommodation prided for them by the river’s side.”[38] Prinsep frames the architecture of the riverfront as a respite from the city’s “poor” design and for this reason suggests that it is here that “the busiest and happiest hours of every Hindoo’s [sic] day: bathing, dressing, praying, preaching, lounging, gossiping, or sleeping.”[39] It was precisely this reading of Varanasi, positioned as in sync with that of the local Hindus, that the British colonial officials used to rationalize their eventual urban renovations—particularly those of its subterranean strata.

Although colonial municipal authority was claimed in part based on a continuity with (and conflation of) previous regimes of governance, it was at best an aesthetic continuation of the riverfront’s architecture, while the base structures of the aqueous city were being radically upended. Vijay Prashad notes that in India, unlike in Europe, the British believed that “miasma emerge[d] out of its very earth,” which was seen as ripe with stagnant waters, swamps, and damp.[40] Whereas the unbounded water that permeated the city, buoyed by religious rituals invented by city elites, was believed by many Hindus to be sacred and cleansing, upon arriving to the aqueous terrain, colonists saw (and felt) a dampness and humidity that posed a threat to the British body.

The diffused waters of Varanasi’s tropical climate and landscape were a source of immense fear for British colonists in the city. It was, however, a colonial understanding (wholly unrelated to Hindu cosmology) of the water conceptually contained as the Ganges River as having the capacity to neutralize the threat of pollutants, which was the basis of many infrastructural projects of the period. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was a popular belief among the British that large-scale collections of water would dilute pollutants, effectively rendering them innocuous.[41] Although water as a substance, the monsoon and the Ganges River included, was viewed with skepticism by the British up until the early twentieth century, fear of the city’s wastes were much greater. The city itself was conceptualized by colonists as a place that required constant washing during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[42] The British sanitarian, Edwin Chadwick, described the city as needing constant lavation in the form of an uninterrupted, brisk flow of water to be swiftly directed through and out of the city limits without a moment of stagnation.[43]

At the command of the second City Magistrate, Jonathan Duncan, who was particularly concerned with urban cleanliness and sanitation, the East India Company’s surveyor for the city of Varanasi, Francis Wilford, reported on the state of the city’s sewage and draining systems in 1790. In his report, Wilford colorfully detailed the “filth and nastiness” and “intolerable stench” he encountered throughout the city. It was not simply the presence of water beyond what colonists defined as the boundaries of the Ganges River basin that drew Wilford’s ire, but particularly locations and infrastructures that collected and allowed water to stagnate. Of one of the city’s primary stepwells, Wilford wrote, “It is the recepticale [sic] of all the drains and filth from the adjacent high grounds. To its banks crowds of people resort all day long on a particular call and the stench occasioned by it is hardly to be described.”[44] Wilford’s report has frequently been cited as the rationale for the colonial project of draining Varanasi’s urban waterscape in an attempt to clearly distinguish and delineate land from water.[45] Though British support for Hindu ritual bathing and Brahminical socio-religious rituals was evident, colonial infrastructural projects quickly rendered the water infrastructure that supported these rituals unusable. While some of these water reservoirs still survive and have been restored from disuse in the more recent past, the majority of those that have survived no longer functionally drain water into the Ganges River, effectively separating the catchment from river basin, rain from river, and ritual from material.

A far cry from the Hindu reverence for rain, Dilip da Cunha explains that British colonists only tolerated rain as they knew it was necessary to keep rivers from running dry. Even still, they did everything possible to “hurry rain into ditches, gutters, pipes, and streams, reducing the time of its ‘informality’ by converting the fall of rain everywhere into flows of water somewhere.”[46] It was this rapid movement of water through the city that James Prinsep made into a reality for Varanasi by redesigning the flow of water as a system of conduits. Prinsep, who had just been named Secretary to the Local Improvement Committee of Varanasi, commented in 1829 that “while the wealthy Indians of Benares were busy embellishing Benares above ground, their conquerors were content to labour in humble brick underground.”[47] Though he recognized the presence of traditional water collection systems, he described them as “stagnant pools and marshes.”[48] Through a series of surveys he took of the city, Prinsep saw an opportunity to quickly direct the aqueous holdings of the catchment along with sewage—both equally thought of as pollution—into the Ganges River basin via an extensive network of interconnected tunnels. Though presented as a sanitation project, the real success of James Prinsep’s sewers was that they reinvented the city of Varanasi to become part of the Ganges drainage system.[49] Beyond moving untreated sewage into the river, this system fundamentally altered Varanasi’s ground plane’s ability to hold, filter, and incrementally drain the monsoon’s rain into the Ganges River basin—in short, severing Ganga from the Ganges.

This urban redesign was rationalized through what Janine Wilhelm refers to as the “Indian paradigm,” which was based on the colonial categorization of the Indian environment as tropical and hence inherently not wanting (or undeserving) of conservation.[50] This colonial belief was the basis of sanitary drainage projects, which ruptured broader eco-religious practices in Varanasi and would eventually create an over-dependence on the Ganges River to accept and “neutralize” urban waste. In its steadfast focus on hygiene, it also essentially converted natural and Mughal-built bodies of water into open sewers and became a notable contributor to the Ganges River’s polluted state today. The ongoing direction of sewage into the Ganges River has set the scene for the still-emergent contemporary tendency to distinguish between the Ganga and the Ganges, to maintain that “the goddess is not affected by material pollution.”[51] Like the riverfront architecture that demonstrated the power and wealth of previous regimes, the colonial administration symbolized its strength in this below-ground infrastructure that also fundamentally changed the political, religious, environmental, and material makeup of Varanasi’s water(front).

Conclusion

If we return to Narendra Modi’s recent evocation of “Ganga Maa” as a call for a radical recoupling of the deity with the Ganges River, we might then also read in it an evocation for a nostalgic return to a pre-colonial and Hindu India. Modi has claimed that his focus on cleaning the Ganges River was one that was divinely prescribed to him: “Maa Ganga has called me… she decided some responsibilities for me. Maa Ganga is screaming for help, she is saying I hope one of my sons gets me out of this filth… it has been decided by God for me to serve Maa Ganga.”[52] Here, the Prime Minister presents Ganga not only as materially manifest as the Ganges River but as having the agency to call for her own cleansing and as a distinct entity from the “filth” that plagues her earthly body. This narrativization of Ganga simultaneously appeals to religious and environmental sensitivities while also validating Modi’s political power. However, it also comes into conflict with the role that Ganga plays as a cleanser of the pollution of the earth herself in Hindu cosmology. While not all Hindus believe that Ganga is capable of cleaning the Ganges, others believe water treatment of the Ganges River as superfluous and many continue to bathe in it and drink its water in search of spiritual purification.[53] Though today the more common Hindu narrative of the river dovetails with Modi’s, it is just one of many understandings of water that have been imposed on this body of water.

The Swachh Barat Abhiyan [Clean India Campaign]’s flagship program focuses on cleaning and rehabilitating the Ganges River. Since it was declared India’s “national river” by Modi’s predecessor, Manmohan Singh, in 2008, the Ganges River has also been deemed among the most environmentally degraded and polluted rivers in the world.[54] The project is rationalized and supported through interconnected imperatives of Hindu religious sanctity, nation building, and economic growth.[55] In his over eleven years (and counting) in office, Modi has operationalized the political dimensions of cleansing the Ganges River to align it with his vision of a mono-religious nation. Through the conservation program, Namami Gange [Bowing to the Ganges River], Modi has consistently reduced the Ganges River to an exclusively earth-bound manifestation of Hindu cosmology.[56]

Yet the process of cleaning the Ganges River through water treatment plants and the rerouting of sewer infrastructures away from the river basin—a solution that has been proposed by postcolonial administrations in India since the 1980s—further exaggerates its status as a river and as a singular and distinct body of water that can be clearly delineated and contained.[57] In these proposed modern interventions for cleaning the pollution of the Ganges, the river is separated further from the “ubiquitous wetness” in which Ganga is present.[58] Even in his harkening back to a pre-colonial religious past, Modi’s transposition of Hindu cosmology onto the bounded Ganges River today is one that never existed as such among Hindus in the period that Modi seeks to position as a religion’s golden age.

In asserting the syncretic and collaborative construction of the Ganges River as it exists today, the ecological and religious weaving in Modi’s narrative comes undone. Modi’s narrative is, however, just one of countless neo-traditional narratives that prize indigenous ecologism in India and place colonial occupation and intervention as solely and uniquely at fault for the environmental degradation and pollution in the country. Subir Sinha, Shubhra Gururani, and Brian Greenberg warn that although this represents a neat narrative, environmental history is just another site in which the “struggle for the construction of and control over a national political memory” is played out and is “not innocent of its own implications.”[59]

Not unlike British attempts to show the Mughal past as having decayed during the eighteenth century, so too can we read Modi’s mediatized attempt to show the environmental degradation of the country at the hands of the British as an opportunity to connect his political power not only to divine intervention but also to a pre-colonial and pre-Mughal, naturalized Hindu antiquity. Due to the fluid dispersal of the monsoon’s wetness, the water that Modi’s narrative attempts to hold must be constantly materially produced and reproduced as a river and be discursively produced and reproduced as Ganga.

Ushma Thakrar is a PhD student at Carleton University’s Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

[1] “Narendra Modi Performs Ganga Aarti in Varanasi,” Times of India, video, May 17, 2014, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/videos/news/Narendra-Modi-performs-Ganga-Aarti-in-Varanasi/videoshow/35266874.cms (all weblinks consulted October 18, 2025). The newly elected prime minister would reiterate this evocation of the goddess Ganga in a later tweet: Narendra Modi (@narendramodi), “I will represent Varanasi in Lok Sabha & I look forward to this wonderful opportunity to serve Ganga Maa & work for Varanasi’s development,” Twitter, May 29, 2014, https://twitter.com/narendramodi/status/472913399494559744.

[2] Narendra Modi quoted in Justin Rowlatt, “India’s Dying Mother,” BBC News, May 12, 2016, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-aad46fca-734a-45f9-8721-61404cc12a39#one-26915.

[3] In October 2014, just five months after being elected, Narendra Modi’s government launched Swachh Bharat Abhiyan [The Clean India Campaign] as a tribute to Mahatma Gandhi. It was claimed to be “the most significant cleanliness campaign by the Government of India.” “Swachh Bharat Abhiyan,” Website of the Prime Minister of India, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/major_initiatives/swachh-bharat-abhiyan/.

[4] Emma Mawdsley, “Hindu Nationalism, Neo-Traditionalism and Environmental Discourses in India,” Geoforum 37, no. 3 (May 2006): 380–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2005.09.004.

[5] Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter (Pegasus Foundation, 1983).

[6] Sugata Ray and Venugopal Maddipati, “Introduction: The Materiality of Liquescence,” in Water Histories of South Asia: The Materiality of Liquescence, eds. Sugata Ray and Venugopal Maddipati (Routledge, 2020), 5.

[7] Today, riparian cities along the entire length of the Ganges River discharge over 2,600 million litres of primarily raw sewage into the river on a daily basis. Janine Wilhelm, Environment and Pollution in Colonial India: Sewerage Technologies Along the Sacred Ganges (Routledge, 2016), 4.

[8] Madhuri Desai, Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City (University of Washington Press, 2017), 73.

[9] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 8.

[10] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 119.

[11] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 73.

[12] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 41.

[13] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 121. On cosmopolitanism, 29.

[14] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 121.

[15] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 7–8.

[16] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 8.

[17] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 7.

[18] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 12.

[19] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 77.

[20] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 78.

[21] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 129–30.

[22] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 77–8.

[23] Mahesh Gogate, The Sacred Waters ‘of’ Varanasi: The Colonial Draining and Heritage Ecology (Manohar, 2023), 15.

[24] Dilip da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 40.

[25] da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers, 230.

[26] Mahesh Gogate, “The Sacred Temple Tanks of Varanasi,” Cultural Heritage of Varanasi, 2021, https://culturalheritageofvaranasi.com/essays/the-sacred-temple-tanks-of-varanasi-2/.

[27] Diana L. Eck, “Ganga: The Goddess Ganga in Hindu Sacred Geography,” in Devi: Goddesses of India, eds. John S. Hawley and Donna M Wulff (University of California Press, 1996), 138–9.

[28] Gogate explains that “various rituals, socio-cultural practices, fairs and festivals are connected not merely with the water reservoirs but also with their catchments areas [that] suitably encapsulate the veneration of water as a cleansing agent.” Gogate, “The Sacred Temple Tanks of Varanasi.”

[29] Charles Lyell cited in Ray and Maddipati, “Introduction: The Materiality of Liquescence,” 5.

[30] da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers.

[31] da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers, 33.

[32] da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers, 33.

[33] In addition to his book, The Invention of Rivers, which looks at this separation in the Indo-Gangetic Plain, da Cunha’s collaboratively authored work with Anuradha Mathur, Soak: Mumbai in an Estuary (Rupa & Co.; 2009) discusses the production of the analogous separation in Mumbai.

[34] Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (Princeton University Press, 1996), 6–11.

[35] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 189–90.

[36] Desai, Banaras Reconstructed, 118.

[37] James Prinsep, Benares Illustrated in a Series of Drawings [1830] (Vishwavidyalaya Prakashan, 1996), 18.

[38] Prinsep, Benares Illustrated, 18.

[39] Prinsep, Benares Illustrated, 18.

[40] Vijay Prashad, “Native Dirt/Imperial Ordure: The Cholera of 1832 and the Morbid Resolutions of Modernity,” Journal of Historical Sociology 7, no. 3 (1994): 251, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6443.1994.tb00065.x.

[41] Wilhelm, Environment and Pollution in Colonial India, 7.

[42] Ivan Illich, H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness (Marion Boyars Publishers, 1986), 52–7.

[43] Edwin Chadwick quoted in Illich, H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness, 53.

[44] Francis Wilford quoted in Bernard S. Cohn, “The British in Benares: A Nineteenth Century Colonial Society,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 4, no. 2 (January 1962): 182–3.

[45] Gogate, The Sacred Waters ‘of’ Varanasi, 1–22.

[46] da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers, 279.

[47] Cohn, “The British in Benares,” 183.

[48] da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers, 271–2.

[49] da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers, 272.

[50] Wilhelm, Environment and Pollution in Colonial India, 8.

[51] Wilhelm, Environment and Pollution in Colonial India, 7.

[52] Narendra Modi quoted in Justin Rowlatt, “India’s Dying Mother,” BBC News, May 12, 2016, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-aad46fca-734a-45f9-8721-61404cc12a39#one-26915.

[53] Kristofer Rhude, “Pollution and India’s Living River,” Harvard Divinity School, https://rpl.hds.harvard.edu/religion-in-context/case-studies/climate-change/pollution-indias-living-river.

[54] Wilhelm, Environment and Pollution in Colonial India, 1.

[55] “Namami Gange,” Website of the Prime Minister of India, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/government_tr_rec/namami-gange/.

[56] Ray and Maddipati, “Introduction: The Materiality of Liquescence,” 4.

[57] Sara Ahmed, “Cleaning the River Ganga: Rhetoric and Reality,” Ambio 19, no.1 (February 1990): 42–5.

[58] da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers, 293.

[59] Subir Sinha, Shubhra Gururani, and Brian Greenberg, “The ‘New Traditionalist’ Discourse of Indian Environmentalism,” Journal of Peasant Studies 24, no. 3 (1997): 90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066159708438643.

Cite this article as: Ushma Thakrar, “’Beneath the Waters of a Universal Ocean’”’: Containing, Contaminating, and Cleaning the Ganges River in Varanasi,” Journal18, Issue 20 Clean (Fall 2025), https://www.journal18.org/8044.

Licence: CC BY-NCJournal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.