Demetra Vogiatzaki

In October 2024, the Musée Carnavalet in Paris opened Paris 1793–1794: Une année révolutionnaire, an exhibition tracing how the city was transformed during Year II of the French Republic.[1] Among the objects on display was a limestone head, severed at the neck, that once formed part of a medieval statue from the Gallery of the Kings on the west façade of Notre-Dame de Paris (Fig. 1). Normally housed at the Musée de Cluny, the fragment had been loaned for the occasion and presented in a protective case beside Hubert Robert’s La violation des caveaux des rois (1793) and Jean-Baptiste Lesueur’s Vandal, Destroyer of the Arts (c. 1793–94). The grouping evoked the now-familiar imagery of revolutionary violence directed against artworks, relics, and architectural symbols of authority, prompting reflection on how political meaning was assigned to acts of destruction.

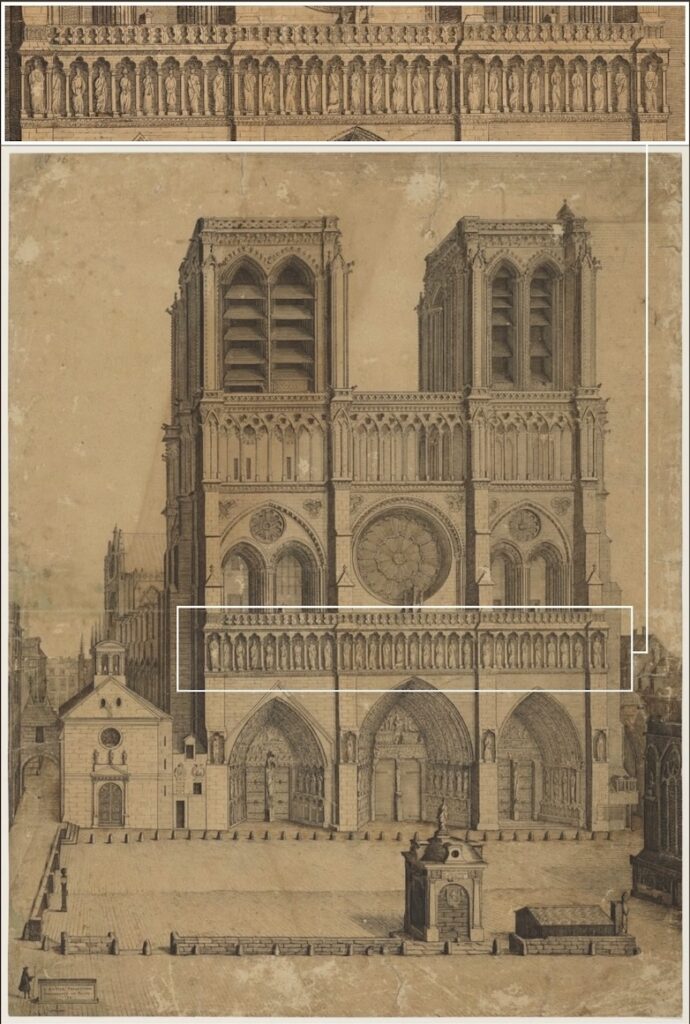

Carved around 1220, the Gallery of the Kings is now understood to represent the kings of Judah, yet early modern writers often read it as a genealogy of the French monarchy (Fig. 2).[2] This conflation of dynastic and sacred lineage rendered the ensemble especially vulnerable in 1793, when the Paris Commune, the municipal government established to enforce revolutionary decrees and reorganize civic life, ordered the eradication of “all monuments that nourish religious prejudice and recall the execrable memory of kings.”[3] Workers climbed the west façade of Notre-Dame, broke the twenty-eight royal figures, and hurled the fragments into the square below, where they were eventually auctioned and carted away as rubble.

The event formed part of a broader campaign of sanctioned destruction that had spread across France since the early days of the Revolution. Equestrian statues of the Bourbon kings were toppled and melted, while cathedrals, monasteries, and parish churches were stripped of their furnishings.[4] Sculptures of the Virgin and of saints were removed, stained glass was shattered, and reliquaries were seized and cast into the national melting pot. These acts extended from Paris to provincial centers such as Lyon, where the façades of the Place Bellecour designed by Robert de Cotte (1656–1735) were razed during the siege of the city following its revolt against the National Convention (Fig. 3).[5] In the years that followed, the term vandalism emerged to describe this surge of politically charged destruction that sought to cleanse the material fabric of the nation of the signs of monarchy and religion.[6]

Later accounts often cast such episodes as eruptions of popular fury, manifestations of ignorance, or conspiracies instigated by counterrevolutionaries and foreign agents.[7] This interpretation has since been challenged by a long line of scholarship. From the early “condemnatory historians” of revolutionary vandalism—Louis Réau, Gustave Gautherot, and François Souchal—to later studies by Erika Naginski, Dominique Poulot, and Richard Clay, scholars have shown that the destruction of royal and religious symbols during the Revolution was rarely spontaneous.[8] More often than not, it was legislated, organized, and executed under official supervision by municipal authorities and hired contractors. The examination of demolition contracts, invoices, and ministerial correspondence revealed an administrative system that coordinated and monitored these actions, turning destruction into a regulated operation that served ideological and, at times, practical ends. This recognition aligns with a broader historiographical argument about the persistence of administration through the apparent rupture of 1789. Following Alexis de Tocqueville, historians such as François Furet and Isser Woloch have contended that revolutionary transformation frequently absorbed and extended existing frameworks rather than replaced them.[9] Architectural historians, including Allan Potofsky, Robert Carvais, and Lauren O’Connell, have further developed this perspective, tracing continuities within the building trades where systems of oversight, accounting, and remuneration structured construction, demolition, repair, and reuse.[10]

This paper builds on these two historiographical directions—administrative oversight and institutional continuity—by examining some of the less visible dimensions of revolutionary iconoclasm. Drawing on sources from the Archives de Paris and the Archives Nationales, it reconstructs the organization of the cleaning of the rubble from the Gallery of the Kings, following the itinerary of fragments through estimates, carts, and sales. The aim here is to clarify how operations of nettoyage on the physical fabric of the monument intersected with what Richard Clay has described as the “transformation of the sculpture-as-sign” during the Revolution.[11] If, for Clay, Dario Gamboni, Richard Wrigley, and other historians of revolutionary vandalism, this transformation was primarily discursive—articulated through decrees, pamphlets, and songs that redefined the meaning of monuments—the present analysis turns to material procedures, such as removal, repair, and redistribution, to consider how these actions both enabled and complicated that symbolic redefinition.[12] Put differently, it suggests that revolutionary efforts to purge the city of its royal and religious symbols converged with practical concerns about hygiene that came to shape civic space at the turn of the century.

Considered in the socio-economic context of the Revolution, these practices further invite a rethinking of creativity itself, shifting attention from invention and single authorship to the collective work of those who maintained, adapted, and reconfigured the built environment within conditions of material scarcity and ideological change.[13] Thus, the following pages turn to a varied cast of actors, from anonymous journeymen traceable only through wage records to contractors and supervising architects whose work unfolded primarily within systems of technical and institutional service rather than monumental creation. Among the latter, particular attention is paid to Louis-François Petit-Radel, a lesser-known architectural bureaucrat eventually charged with cleaning up the parvis of Notre-Dame and auctioning the broken fragments from the Gallery of the Kings as construction materials.[14]

Through reports, estimates, and correspondence, this essay reconstructs an operational logic in which architecture and sculpture were treated as both charged and expendable matter, suspended between their status as emblems of a discredited order and their value as reusable materials. It argues that revolutionary iconoclasm in Paris, exemplified by the destruction and subsequent clearance of the Gallery of the Kings at Notre-Dame, cannot be understood solely as a political or symbolic act. Rather, it must also be read as a material process that unfolded through mundane routines of cleaning, valuation, and redistribution. The work of contractors, sculptors, architects, and administrators reveals how symbols converted into measurable units of materiality, weight, and labor, as questions of cleanliness and reuse helped structure ideological change. To recover this material infrastructure of governance is then to return to the quiet efficiency of those, like Petit-Radel, whose inconspicuous work underwrote the spectacle of destruction, rendering the remnants of the Revolution orderly, measurable, and clean.

Kings to Rubble

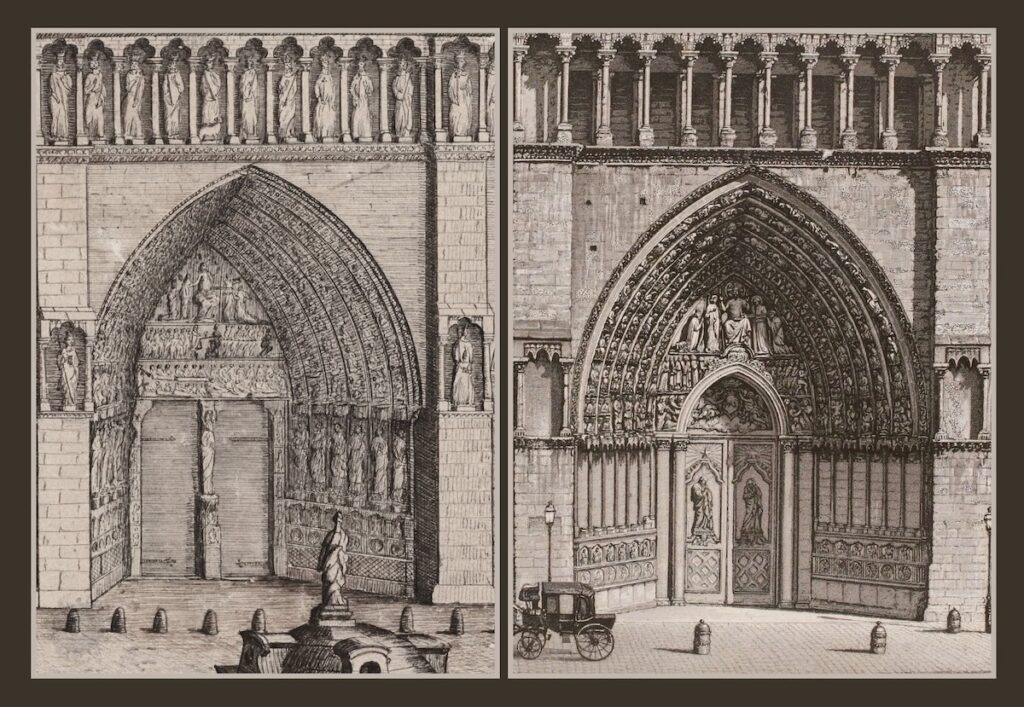

Long before the iconoclastic directives of Year II, Notre-Dame had undergone successive alterations driven by liturgical reform, royal patronage, and changing aesthetic norms. Later described by Marcel Aubert and Paul Vitry as “sacrilegious and absurd,” these transformations were carried out by leading architects of the ancien régime, including Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Robert de Cotte, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, Germain Boffrand, Pierre Fontaine, and Charles Percier.[15] Among the most striking and widely criticized interventions was the 1771 demolition of the tympanum of the central portal of the west façade, undertaken under Soufflot to widen the entrance and facilitate processions. The operation destroyed the thirteenth-century reliefs of the Resurrection of the Dead and the Weighing of Souls, essential elements of the Last Judgment iconography that framed the portal, and permanently altered its composition and symbolic coherence (Fig. 4).[16]

Left: Detail from Vincent Hantier, Western Facade of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, 1699. Pen and pencil drawing, 59.2 × 46.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Image Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Right: Detail from Portal of Notre-Dame in Paris. Daguerreotype in Noël-Marie Lerebours, Excursions daguerriennes: vues et monuments les plus remarquables du globe (Paris, 1840-43). Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Image Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Such perceived “assaults” encompassed not only large-scale commissioned alterations but also the cumulative impact of routine maintenance and repair. These operations, entrusted to lesser-known architects and contractors, were frequent and often dictated by necessity. Contemporary reports reveal that the exterior of Notre-Dame demanded continual attention throughout the eighteenth century, as the effects of time, weather, and neglect repeatedly compromised its structural fabric. A 1744 inspection by Pierre-Charles de Lespine and Nicolas Parvy, for example, described the structure as dangerously deteriorated.[17] In 1781, another report noted critical failures in the choir and flying buttresses, where thin stone veneers had detached under the effects of rain and frost; damage attributed to cost-saving measures that had weakened the masonry.[18] Similar problems recurred in 1787, when Parvy resumed work on the roof and drainage systems. The masonry contractor had removed applied columns from the tower buttresses, leaving the trefoils projecting in cantilever and distorting the geometry of the façade. Writing in the early nineteenth century, Antoine Gilbert lamented that successive campaigns of whitewashing in 1728, 1780, and 1804 had deprived the church of the “dark and venerable patina accumulated over centuries.”[19] Other alterations, including the replacement of gargoyles, were viewed as attacks on the original architecture carried out under the pretext of safety, betraying an open hostility toward Gothic forms and a “misguided zeal to deform them wherever they were encountered.”[20]

An invoice by Pierre-Louis Fixon, sculptor to the cathedral chapter, offers a rare insight into the practices and values that guided eighteenth-century maintenance and complicates these later judgments. Compiled between 1772 and 1773, at the same time that Soufflot was transforming the central portal, the so-called Dossier Fixon details restorations on the two lateral portals of the west façade.[21] In it, Fixon listed hundreds of delicate grafts in new Conflans stone: hands, heads, toes, and entire bas-reliefs reattached or replaced, each entry accompanied by a price, revealing a careful system that translated craftsmanship into measurable units of labor and cost. The report also records that replacement pieces were modeled in clay directly on the stone surface and tinted d’une couleur grise to harmonize with the existing material. Coming from a family long employed at the cathedral, Fixon approached the building as a structure in perpetual repair, rather than as an untouchable relic: an attitude that would resurface decades later within a different ideological climate, one that repositioned maintenance within evolving administrative economies of revolutionary destruction.

From the early days of the Revolution, efforts to remove visible symbols of monarchy and religion coincided with attempts to preserve selected fragments as evidence of an enlightened relation to history. This tension, described by Andrew McClellan as the coexistence of “contradictory revolutionary desires,” informed both state-directed and individual-led initiatives.[22] One of the most visible was the work of Alexandre Lenoir, who in 1795 founded the Musée des Monuments Français in the deconsecrated convent of the Petits-Augustins.[23] There he assembled sculptures, tombs, and architectural fragments removed from churches and royal sites after the decrees of Year II, arranging them in chronological sequence to demonstrate the progress of national artistic production. As Dominique Poulot has shown, such early preservation efforts and the nascent idea of national heritage were often framed as a rational continuation of revolutionary iconoclasm rather than as its denial.[24] This logic extended to administrative practice, where limited resources and competing interests required those charged with dismantling churches to distinguish quickly between what could be reused, sold, or saved, and what had to be eliminated—decisions that often blurred as responsibility shifted through layers of oversight to the hands of those working on the scaffolds.[25]

In this vein, a revealing example is the case of François Daujon, a contractor, administrateur des travaux publics, who built a career during the Revolution by stripping churches of feudal and royal symbols. Gustave Gautherot, in his study of “Jacobin vandalism,” devoted an entire section to him, portraying Daujon as a jacobin iconoclaste par excellence.[26] Yet Daujon’s own reports appear to complicate that image. For Richard Clay, Daujon, who claimed to have “carried and arranged in a chapel all the marbles, stones, bronzes and lead to ensure that nothing is lost or broken,” effectively performed a triage, salvaging what he deemed aesthetically or historically valuable while fulfilling municipal orders.[27] Poulot likewise argues that such acts of discernment were integral to a contemporary distinction between the “barbarians” and those professionals who, as “vandalic artists,” practiced the art of destruction with method and discrimination.[28]

A comparable dynamic unfolded at Notre-Dame. In September 1793, the Revolutionary Committee of the Section de la Cité placed the dismantling of royal insignia under the supervision of a contractor named Bazin, who, like Daujon, had previously directed the removal of crowns, fleurs-de-lis, and other emblems of sovereignty from public buildings across Paris.[29] Between 10 September and 4 October of that year, Bazin and his team erected a fifty-foot scaffold and began chipping away the fleurons from the crowns of the kings and queens that adorned the west façade.[30] The operation at this stage targeted insignia, not figures; the statues themselves remained in place.[31] The results, however, were judged inadequate, too cautious and restrained for the expectations of the authorities, and on 23 October of Year II the Commune issued a more radical directive: “Within eight days, the Gothic simulacra of the kings of France which are placed at the door of Notre-Dame will be brought down and destroyed.”[32]

Responsibility for this second phase was transferred to a new contractor, Varin, but the appointment soon provoked a dispute over control of the site. Competing contractors advanced overlapping claims, each citing patriotic service and professional experience to secure the commission.[33] Among them, François Daujon and the sculptor Citizen Bellier appealed to “the justice of the Commission, which, following the intention of the National Convention, employs those citizens who have most devoted themselves to the cause of Liberty,” arguing that their long involvement in “the suppression of feudal symbols and in demolitions and transports for the Nation” entitled them to the work.[34] Their petition was challenged by Citizen Scellier, a marbrier already collaborating with Varin, who presented his own official mandate before the Commission.[35] After deliberation, the Commission upheld Scellier’s claim, assigning Daujon and Bellier instead to assist in clearing other churches of “precious objects in the arts that the Commission felt it necessary to reserve.”[36]

The invoice submitted by Varin, preserved in the Archives Nationales, records the technical precision with which the operation unfolded.[37] Flying scaffolds and pulley systems were used to remove coats of arms, altarpieces, and monumental figures. The statues of the kings presented particular difficulties: carved in hard stone and anchored with iron clamps, they could not simply be toppled. According to Varin’s invoice, the process required the mutilation and gradual reduction of each sculpture. Shoulders, draperies, and necks were broken off to permit extraction through the colonnade, after which the fragments were lowered to the parvis using hoists and levers. By the end of the campaign, Varin reported the destruction of seventy-eight large statues and twelve smaller ones across the former cathedral, not counting columns and framing elements bearing royal insignia.

Symbolisms of Waste

After the statues from the Gallery of the Kings were toppled in October 1793, their fragments remained scattered across the parvis of the church.[38] Many heads, including the one exhibited at the Carnavalet, shattered upon impact, and the heavy blocks cracked the paving. When repairs began, workers moved the debris to the northern side of the cathedral, where it lay for nearly three years.[39] In his later writings on Paris, Louis-Sébastien Mercier described the heap as a “mountain of refuse,” grotesque and foul-smelling.[40] “Thus stands in Paris the new Saint-Denis,” he observed, recalling the royal necropolis desecrated only months earlier.[41] The tombs of French monarchs were opened, their remains thrown into common pits, and the effigies dismantled in what Erika Naginski has described as “ritualistic encores of royal executions.”[42] The analogy with Notre-Dame was deliberate, further drawing upon a longstanding moral economy of purity and corruption that had also informed the profanation of the royal tombs at Saint-Denis.[43] Revolutionary songs framed the opening of the graves as a purifying act: “Let us cleanse the soil of patriots of the kings who still infect it,” urged a journalist in the Moniteur.[44] In Les Révolutions de Paris, Sylvain Maréchal voiced the same demand: “While we are in the process of erasing every trace of royalty, how is it that the impure ashes of our kings still rest intact in the former abbey of Saint-Denis?”[45]

The moral language of revolutionary purification extended beyond religious symbolisms. Historians such as Allan Potofsky, Antoine Picon, and Richard Etlin have traced the emergence, in the late eighteenth century, of a civic discourse on cleanliness and public hygiene that reflected the anxieties of an expanding urban bourgeoisie.[46] Although Paris was considered one of the best-paved cities in Europe, it remained chronically muddy, a condition worsened by construction, demolition, and the unregulated dumping of waste.[47] The problem intensified during moments of rapid urban growth, first under the Regency (1715-23) and again in the 1770s and 1780s, when renewed building activity left the streets saturated with a viscous mixture of earth, rubble, and refuse.[48] These conditions created both hygienic and logistical challenges, what Léon Bernard later described as an “extraordinary disorder” that pushed the urban infrastructure to its limits.[49] It was against this backdrop that public debates over urban maintenance took on moral significance, merging environmental concern with civic virtue. As Potofsky notes, in the cahiers de doléances of 1789, the petitions drafted by representatives of the three estates to articulate social and political grievances, residents condemned the pollution caused by unchecked construction, treating it as a visible symptom of monarchical waste.[50] Such grievances framed the city itself as an object of moral reform, where physical cleansing could stand for civic regeneration.

By 1795, two years after the height of revolutionary iconoclasm, the political climate had shifted from militant purification to cautious reconstruction. The Thermidorian regime sought to reestablish order and reconcile with religion, even as the material traces of earlier destruction remained unresolved. As preparations began for the resumption of Catholic worship at Notre-Dame, the church was still obstructed by debris, both inside and out. When the architect Jacques-Guillaume Legrand inspected the site in July, he found the nave galleries and side aisles filled with army wine barrels, and the choir blocked by marble fragments.[51] Official reports blamed the delay in clearing the site on a shortage of carts, but the situation reflected a broader administrative confusion, recalling the overlapping jurisdictions and rival claims that had complicated the work of demolition two years earlier. It was unclear which authority had ordered the removals and which was now responsible for restoring liturgical use.[52]

It was within this atmosphere of administrative fatigue that complaints from local residents prompted the police commissioner of the Section de la Cité to intervene regarding the debris that still covered the parvis of Notre-Dame. Reports cited blocked passageways, foul odors, and fears that the piled fragments offered concealment for illicit activity.[53] The case was referred to the Ministry of the Interior, which in turn consulted the municipal architect Bernard Poyet. A long-serving official in public works, Poyet specialized in infrastructure, water distribution, and hospital reform, where questions of hygiene and ventilation linked architecture to public health.[54] In his report on Notre-Dame, he confirmed the urgency of the situation, describing both the unsanitary conditions and the hazards created by the accumulated rubble. He proposed transferring the fragments to the contractor then employed at the Hôtel-Dieu, with the stones serving as payment in kind to offset the cost of removal while fulfilling a civic purpose.[55] Correspondence held at the Archives de Paris shows that the proposal stalled, once again, amid overlapping jurisdictions and competing claims to the materials.[56]

Responsibility for the site eventually passed to Louis-François Petit-Radel, who was not entirely new to the cathedral. In 1777, the Journal de Paris recorded his participation in the installation of granite bénitiers at the cathedral entrance, a collaborative commission that also served to advertise his expertise in hard stonework.[57] Nearly twenty years after his first documented work at Notre-Dame, on 27 March 1796, he submitted a report addressing the accumulation of debris that still obstructed the north side of the church. He emphasized the urgency of its removal, noting the severe limitations imposed by the shortage of funds, carts, and horses.[58] His proposal, similar to that of Poyet, was pragmatic: to sell the stones as rubble directly from the site, on the condition that the purchaser clear the area immediately and leave it clean. He estimated the total volume at one and one-third cubic toises, roughly five cubic meters, and noted the exceptional hardness of the stone, proposing a value of 250 livres.[59] Unlike Poyet, he ensured that his plan was carried out.

On 15 June 1796, the fragments were sold at public auction for 380 livres to a contractor named Bertrand, who resided on the Île de la Cité.[60] The terms required him to remove the material within twenty-four hours under Petit-Radel’s supervision. Progress was slow, however. Two weeks later, only two cartloads had been taken away, and the archives again record signs of administrative conflict. Petit-Radel blamed the architect of the Hôtel-Dieu, who claimed priority over the stones and obstructed their removal. In the summer heat, the odor became intolerable, prompting renewed complaints from residents and further pressure on the authorities to act. By early September, Petit-Radel confirmed that the site had, at last, been cleared.

Economies of Waste

In the aftermath of these operations at Notre-Dame, figures such as Bernard Poyet and Louis-François Petit-Radel exemplify a generation of architects whose ambitions were gradually absorbed into the machinery of public administration. Petit-Radel is particularly illustrative in this respect. By the mid-nineteenth century, critics had recast his interventions as acts of aesthetic violence, consistent with the project he presented at the Salon of 1800: a method to destroy a Gothic church with fire in under ten minutes.[61] Writing in the Annales archéologiques in 1845, Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus derided the proposal as a grotesque emblem of technocratic arrogance, exclaiming, “Ten minutes! Twenty at most to destroy the cathedrals of Reims, Chartres, or Amiens; this is what we call to get ahead of oneself!”[62] Petit-Radel’s name was soon associated with the demolition of Saint-Jean-en-Grève, where he was said to have tested his fire-based methods out of an abundance of iconoclastic zeal.[63]

Archival sources present a more complex picture. Records on the demolition of Saint-Jean-en-Grève held at the Archives Nationales trace a protracted process in which technical evaluation and administrative decree became inseparable. Petit-Radel visited the site repeatedly, recording structural fissures, dislodged stones, and the general instability of the vaults. His report described a building so degraded that its preservation appeared dangerous, concluding that demolition was the only responsible course. The operation he would eventually supervise was projected to last eight months, not ten minutes, with orders to transfer elements deemed worthy of preservation to Alexandre Lenoir’s dépôt. In a later report he made sure to note that “the demolition of this church was carried out by decision of the Minister of Finance (…) prompted by the central bureau of the canton of Paris, which was justly alarmed by the state of degradation in which it found the building and by the imminent danger its preservation would have posed to citizens.”[64] Correspondence preserved at the Archives de Paris confirms his words: a letter of 9 Fructidor Year IV (26 August 1796) from the canton of Paris requests the immediate action of the authorities, reporting that a mass of masonry had already fallen from the structure, fortunately without injury.[65]

Petit-Radel reappeared at Notre-Dame a few years following the removal of the debris, as overseer of a campaign of structural repairs. On 1 September 1797, he responded to a petition from Citizen Gilbert, the church guardian, who warned of advanced decay that threatened both public safety and the integrity of the structure.[66] No substantial maintenance, Gilbert noted, had taken place for nine years, apart from minor work on the roof and glazing.[67] In successive reports and cost estimates, Petit-Radel described the deterioration of the roof, stained glass, clockworks, and balustrades. He drew particular attention to the dangers posed by clogged gutters and eroded joints, urging that rainwater channels be cleared “so that the water may find no obstacle to its flow.”[68] Among the most urgent hazards was a braced sapine, a thirty-three-foot mast capped with iron, leaning against the gallery parapet and in danger of collapse.[69] Petit-Radel closed his report in the same pragmatic spirit that had guided his earlier interventions with the debris from the Gallery of the Kings: the operation, he argued, would require almost no expenditure, since the materials could be reclaimed.[70] His detailed valuations assigned 24 francs to the wooden mast and 19 francs 80 centimes to the iron bar and buttresses, yielding a total salvage value of 43 francs 80 centimes.[71]

Petit-Radel’s treatment of royal remains, along with his proposals to demolish Gothic churches or sell sculptural fragments as rubble, appear consistent: matter once regarded as sacred was reclassified as waste, and waste as usable surplus. Paris itself operated within a similar economy of reuse: eighteenth-century households routinely reprocessed leftovers, rendered fats for lighting and cleaning, converted ash into lye and the city routed urban waste to agricultural use.[72] Such domestic and artisanal habits found institutional expression in municipal regulation. A royal ordinance of 1720, for example, required farmers from surrounding villages to collect refuse from municipal depots, including street and construction debris, and to repurpose it as manure for cereal crops.[73] Yet this system often faltered. When rural demand declined or depots overflowed, waste returned to the streets, compelling municipal authorities to intervene. By 1780, Paris was producing close to 750 cubic meters of refuse each day, a volume that provoked new debates over how much the city could discharge and how much the countryside could absorb.[74] As Potofsky has observed, the 1790s brought a new intensity to this process, redirecting it toward the physical fabric of the city.[75] The expropriation and sale of ecclesiastical and aristocratic holdings reconfigured Paris into a terrain of extraction and circulation: former estates were stripped for parts, their stones, iron, and rubble entering a rapidly expanding trade in building materials. What had once been elements of sacred or aristocratic architecture were reclassified as raw resources, circulating within a regulated economy of reuse that linked demolition sites, workshops, and new constructions across the city.

This material economy had its counterpart in a new social and administrative order that redefined the organization of labor. Within the revolutionary building trades, Potofsky situates this development in an ethos of sans-culottisme: “a political economy of social utility and productive labor” that distinguished skilled workers from the unregulated poor.[76] With the dissolution of the guild system in 1791, this mentality informed new forms of labor management directed by municipal and central administrations. It produced a corps of technically trained agents who operated as mediators for the state and the working population, overseeing and controlling the organization of labor.[77] Petit-Radel’s career exemplified this interdependence of expertise, surveillance, and regulation. His entry into public service dated to 1769, when he purchased the office of juré-expert de la ville de Paris from Jean Grissot.[78] As Robert Carvais has shown, these sworn building experts not only oversaw construction but also arbitrated disputes concerning materials, deliveries, and fees.[79] Their authority was intrinsically disciplinary: charged with regulating their peers, they embodied the Crown’s strategy of internal policing within the building trades.[80] Petit-Radel soon became a familiar figure within this administrative machinery of construction. From 1770 onward, his name recurred almost weekly in the registers of the Chambre des Bâtiments, tracing a steady rhythm of inspections and reports.[81] Later, as inspector general at the Conseil des bâtiments civils, the body charged with overseeing the reconversion of nationalized religious properties and confiscated estates, Petit-Radel continued to operate within the expanding framework of state administration.[82]

It was in this capacity that years later he responded to a proposal by Joseph-Balthasar Bonet addressed to the Ministry of the Interior.[83] Bonet suggested installing a Museum of French Monuments within Notre-Dame. The project was referred the following day to the Council and assigned to Petit-Radel for evaluation. The latter’s report, presented on 12 Floréal Year VIII (2 May 1800), provided the grounds for the Council’s rejection of the plan. He observed that all necessary expenses for housing the collection had already been made at its existing site, and that moving it elsewhere would entail vast additional costs “without avoiding the risk of adding new ruins to the old ones.”[84] His argument, framed in the language of fiscal caution and structural preservation, reaffirmed the principles that had guided his earlier interventions at Notre-Dame: conservation through economy, and repair through the efficient management of matter.

Rubble to Kings

In April 1977, maintenance work in the courtyard of the Banque française du commerce extérieur at 20 Rue de la Chaussée-d’Antin revealed a cache of medieval sculptural fragments beneath the paving stones.[85] One of the first objects unearthed was mistaken for a human skull, but the assistant director of the bank, Mr. Dufort, an amateur archaeologist, soon identified it as a carved head. Further excavation revealed twenty-one of the twenty-eight heads from the Gallery of the Kings, including the one later exhibited at the Carnavalet.[86] Only fragments retaining human features, especially faces and hands, had been buried with care, a gesture that suggested reverence rather than aesthetic preservation.[87] Their burial appeared deliberate, each head placed face down and oriented toward the cathedral.[88]

Once unearthed, the fragments were swiftly recast within art-historical frameworks. Described as “one of the most important discoveries of all times in the field of medieval art,” the sculptures found at the Hôtel Moreau quickly drew public and scholarly attention.[89] Within weeks, the Banque organized an exhibition at the Musée de Cluny, followed by shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1979) and the Cleveland Museum of Art (1980).[90] In the accompanying catalogues, historians and archaeologists reconstructed the trajectory of the statues, from their thirteenth-century creation to their twentieth-century recovery from the rubble, inviting speculation about the motives behind their burial and about the meanings attributed to them in the aftermath of Petit-Radel’s actions in 1793.

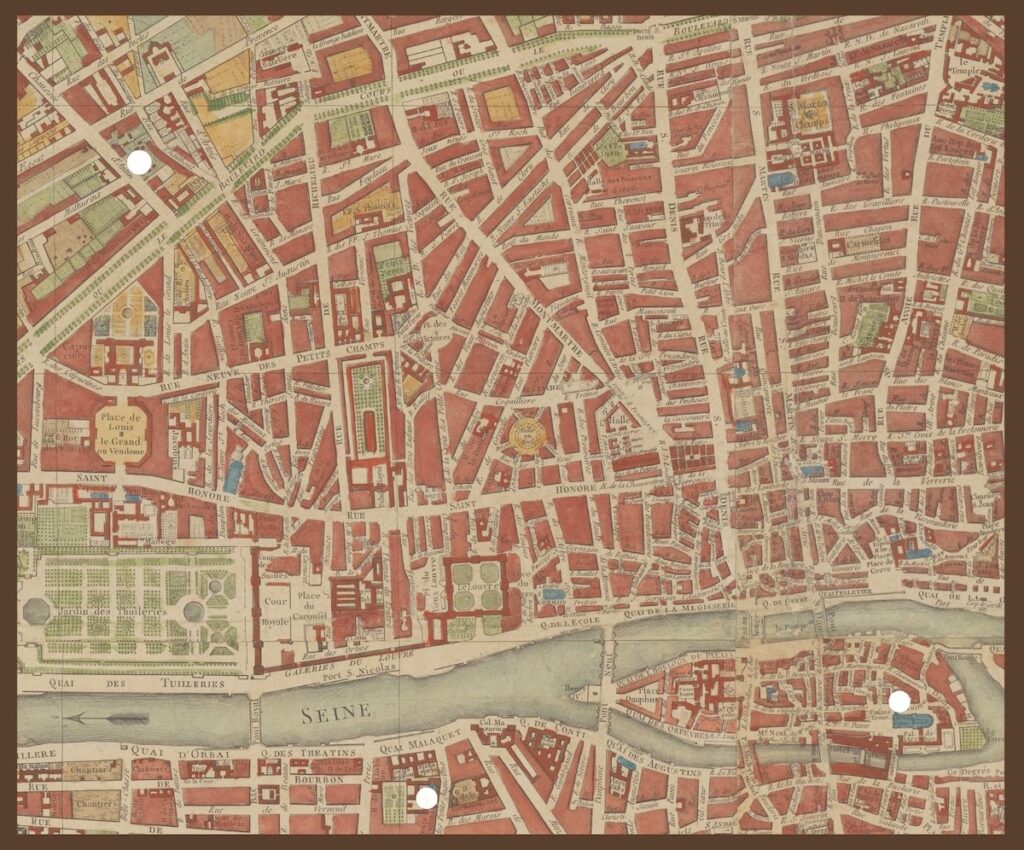

Base map: Detail from M. Pichon, New Road Map of the City and Suburbs of Paris, 1789. Engraved map, 99 × 142 cm. Paris: Esnauts et Rapilly. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Image Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

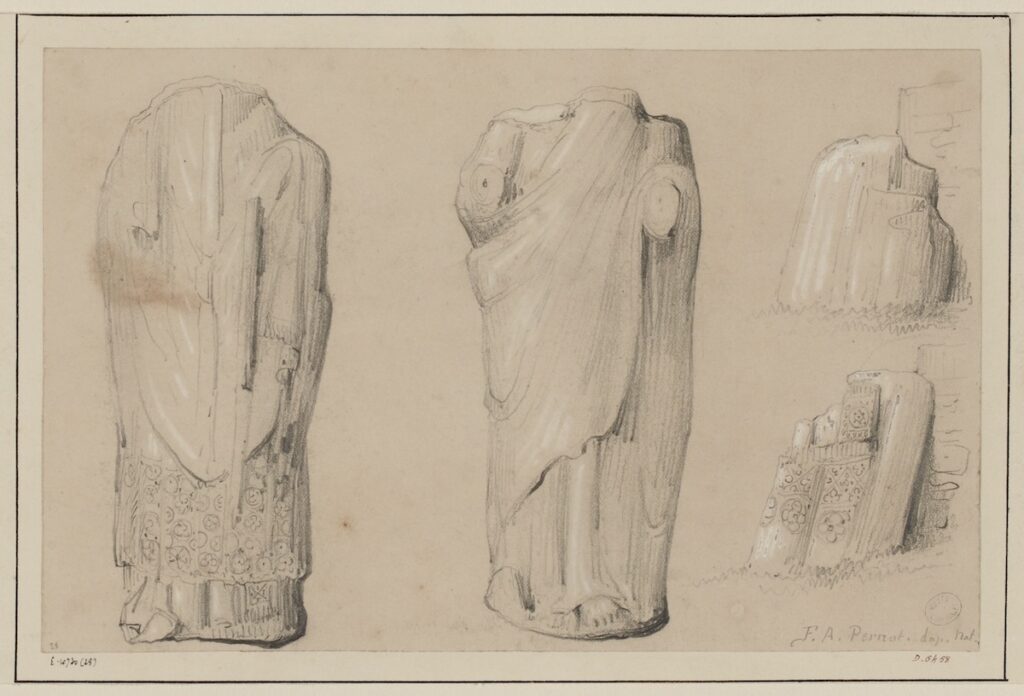

What followed is uncertain, but the rediscovery of 1977 provides a likely trace of their first dispersal. Bertrand, the contractor who had purchased the debris from Petit-Radel, appears to have resold part of it to Jean-Baptiste Lakanal for the construction of his house on the rue de la Chaussée-d’Antin (Fig. 5).[91] Similar instances of reuse had occurred elsewhere. In 1839, fifteen mutilated torsos from the statues of the kings were uncovered, upright and headless, embedded as structural ballast in the perimeter wall of the Marché au charbon on the rue de la Santé. The artist François-Alexandre Pernot documented the discovery in a series of crayon drawings: one depicts the torsos half-buried and propping up the wall (Fig. 6), while another reimagines two fragments as relics, framed by vignettes of their recovery (Fig. 7).

Other fragments entered different circuits of redistribution. Pierre-François Palloy, the entrepreneur known for organizing the demolition of the Bastille and distributing its stones as civic relics, swiftly claimed three heads from Notre-Dame, which he presented as revolutionary trophies to the districts of Égalité, Franciade, and Sceaux-l’Unité.[92] The artist Jacques-Louis David went further still, proposing in 1793 that the shattered kings form the base of a colossal bronze statue of the French people, to rise on the Pont Neuf in place of the dismantled monument of Henri IV.[93] Where Palloy’s intervention relied on circulation and fragment display, David envisioned a single, unified monument: cast in bronze, it would represent the sovereign people triumphing over “fanaticism, royalism, and federalism,” quite literally founded on the shattered kings of Notre-Dame. A decree soon followed from the Committee of Public Safety, instructing the Public Works Commission to collaborate with David for its rapid execution. Yet, like many revolutionary projects, the monument was never realized.

In Mercier’s satire and in the syncretic form of David’s unrealized monument, the dialectic of preservation and destruction found its most striking expression. Both were rhetorical projects that sought, within the field of imagination, to resolve the antithesis between ruin and creation, granting the rubble a retrospective unity. The work of municipal agents such as Poyet and Petit-Radel, by contrast, unfolded in a different register. Their task was not to symbolize but to manage: to clear, repurpose, or sell. Their actions took place within the everyday mechanisms of administration, where symbolic meaning was translated into the procedural banality of valuation, storage, and disposal. Largely invisible within dominant modes of representation and theory, Poyet’s and Petit-Radel’s interventions were meant to remain unseen, carried out in the margins of routine governance. The eventual unearthing of the statues in 1977 marked a rupture in this regime of invisibility, exposing the traces of a work of clearance whose very purpose had been to efface itself.

Demetra Vogiatzaki is a Visiting Lecturer at the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (gta/ETH) in Zurich, Switzerland

[1] Valérie Guillaume, ed., Paris 1793–1794: Une année révolutionnaire (Musée Carnavalet–Histoire de Paris, 2024).

[2] The iconography of the Gallery of the Kings has raised long debates. Most historians agree today that it portrays biblical figures. See Marcel Aubert and Paul Vitry, La cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris: notice historique et archéologique (Longuet, 1909), 93–4; Alain Erlande-Brandenburg and Dieter Kimpel, “La statuaire de Notre-Dame de Paris avant les destructions révolutionnaires,” Bulletin monumental 136, no. 3 (1978): 213–66, 230; François Giscard d’Estaing, “Les rois retrouvés de Notre-Dame de Paris,” La Nouvelle Revue des Deux Mondes (1978): 619–24, 622–3. For the opposite view, see Dany Sandron, Notre Dame Cathedral: Nine Centuries of History (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020), 69.

[3] Guillaume, Paris 1793–1794, 96; Michel Fleury, “Histoire d’un crime,” in Les rois retrouvés, ed. Joël Cuenot (Paris, 1977), 15.

[4] There is an extensive literature on the toppling of equestrian statues during the Revolution. See, for example, Andrew McClellan, “The Life and Death of a Royal Monument: Bouchardon’s Louis XV,” Oxford Art Journal 23, no. 2 (2000): 1–28.

[5] On the siege of Lyon, see William D. Edmonds, Jacobinism and the Revolt of Lyon, 1789–1793 (Oxford University Press, 1990), especially chap. 8, “The Siege.”

[6] The term vandalism is commonly attributed to Bishop Henri Grégoire, whose widely cited Mémoire sur les destructions opérées par le vandalisme was read before the National Convention in January 1794. In that address, Grégoire condemned the “destructive spirit” of the preceding years, referencing widespread acts of iconoclasm and book burning. To frame these events, he invoked the sack of Rome, drawing on Enlightenment anxieties about the fall of the Roman Empire and its resonance with the collapse of civilization. See Keith Bresnahan, “On ‘Revolutionary Vandalism,’” Architectural Theory Review 19, no. 3 (2014): 278–98; and Pierre Marot, “L’abbé Grégoire et le vandalisme révolutionnaire,” Revue de l’Art 49 (1980): 36–9. However, as Richard Clay has shown, the term vandalisme had already appeared in a report submitted by Joseph Lakanal to the Convention in June 1793, where it was used to denounce the destruction of the nation’s cultural heritage. See Richard Clay, Iconoclasm in Revolutionary Paris: The Transformation of Signs, SVEC 2012:11 (Voltaire Foundation, 2012), 268

[7] The timeline of this rhetoric is traced by Gustave Gautherot in Le vandalisme jacobin: destructions administratives d’archives, d’objets d’art, de monuments religieux à l’époque révolutionnaire, d’après des documents originaux, en grande partie inédits (Beauchesne, 1914), vi–ix. See also Richard Wrigley, “Breaking the Code: Interpreting French Revolutionary Iconoclasm,” in Reflections of Revolution: Images of Romanticism, ed. Alison Yarrington and Kelvin Everest (Routledge, 1993), 185.

[8] Louis Réau, Histoire du vandalisme: Les monuments détruits de l’art français (Robert Laffont, 1994); Gautherot, Le vandalisme jacobin; François Souchal, Le Vandalisme de la Révolution (Nouvelles Éditions Latines, 1993); Erika Naginski, Sculpture and Enlightenment (Getty Research Institute, 2009); and Dominique Poulot, “Revolutionary ‘Vandalism’ and the Birth of the Museum: The Effects of a Representation of Modern Cultural Terror,” in Art in Museums: New Research in Museum Studies, ed. Susan M. Pearce (Continuum, 2000), 192–214. The phrase “condemnatory historians” is borrowed from Clay, Iconoclasm, 274.

[9]Alexis de Tocqueville, L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution (Paris, 1856); François Furet, Penser la Révolution française (Gallimard, 1978); and Isser Woloch, The New Regime: Transformations of the French Civic Order, 1789–1820s (W. W. Norton, 1994).

[10]Allan Potofsky, Constructing Paris in the Age of Revolution (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Robert Carvais, “Le statut juridique de l’entrepreneur du bâtiment dans la France moderne,” Revue historique de droit français et étranger 74, no. 2 (1996): 221–52; and Lauren M. O’Connell, “Redefining the Past: Revolutionary Architecture and the Conseil des Bâtiments Civils,” The Art Bulletin 77, no. 2 (1995): 207–24.

[11] Clay, Iconoclasm, 135.

[12] Clay, Iconoclasm; Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution (Reaktion Books, 1997); and Wrigley, “Breaking the Code.”

[13] Ariane Fennetaux, Amélie Junqua, and Sophie Vasset, “Introduction: The Many Lives of Recycling,” in The Afterlife of Used Things: Recycling in the Long Eighteenth Century (Routledge, 2015).

[14] Biographical entries on Petit-Radel are sparse, partial, and often confuse his name, date of birth, and deeds with those of his brothers. The first systematic reconstruction of his life and work, based on archival records, is presented in Demetra Vogiatzaki, “Dreaming in the Age of Reason” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2023; forthcoming book).

[15] Aubert and Vitry, La Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, iii–iv; Marcel Aubert, “Les architectes de Notre-Dame de Paris, du XIIIe au XIXe siècle,” Bulletin Monumental 72 (1908): 427–41, 439.

[16]Richard Winston, Notre-Dame de Paris (Newsweek Book Division, 1971), 108. On Soufflot’s interventions, see René Farcy, “Les travaux de Soufflot à Notre-Dame de Paris,” La Cité: Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique du IVe arrondissement de Paris 21, no. 113 (1930): 135–43; and Erlande-Brandenburg, “Nouvelles remarques sur le portail central de Notre-Dame de Paris,” Bulletin Monumental 132, no. 4 (1974): 287–96.

[17] Aubert and Vitry, Le Cathedrale, 30.

[18] Gilbert, Description historique, 111, 134.

[19] Gilbert, Description historique, 154.

[20] Aubert, “Les architectes,” 439; Gilbert, Description historique, 234; Winston, Notre-Dame, 107–9.

[21] The Dossier Fixon is transcribed and discussed in Erlande-Brandenburg and Kimpel, “La statuaire de Notre-Dame.”

[22] Andrew McClellan, Inventing the Louvre: Art, Politics, and the Origins of the Modern Museum in Eighteenth-Century Paris, 4th ed. (University of California Press, 2009), 155.

[23] On Alexandre Lenoir, see Dominique Poulot, “Alexandre Lenoir et le Musée des Monuments Français,” in Les lieux de mémoire, vol. 2, La nation, ed. Pierre Nora (Gallimard, 1986), 497–533; and Christopher M. Greene, “Alexandre Lenoir and the Musée des Monuments Français during the French Revolution,” French Historical Studies 12 (1981): 203–22.

[24] Poulot, “Revolutionary ‘Vandalism,’” 201.

[25] Clay, Iconoclasm, 217.

[26] See chap. 7 in Gautherot, Le vandalisme jacobin.

[27] Clay, Iconoclasm, 211.

[28] Poulot, “Revolutionary ‘Vandalism,’” 204–5.

[29] AN F13/966, transcribed and discussed in Erlande-Brandenburg and Kimpel, “La statuaire de Notre-Dame,” 213–66.

[30] On Bazin’s operations, see also Clay’s description in Iconoclasm, 219–24.

[31] Carmen Gómez-Moreno, Sculpture from Notre-Dame, Paris: A Dramatic Discovery (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979), 8–9; Clay, Iconoclasm, 219.

[32] Fleury, “Histoire d’un crime,” 15.

[33] Clay, Iconoclasm, 223–24.

[34] Louis Tuetey, Procès-verbaux de la Commission des monuments, 1790–1794 (N. Charavay, 1902), session “Le sextidi de la troisième décade du frimaire de l’an II de la République française, une et indivisible (16 décembre 1793),” signed by F.-V. Mulot, 111–3. See also the discussion in Clay, Iconoclasm, 223–4.

[35] Louis Courajod, Deux épaves de la chapelle funéraire des Valois à Saint-Denis: aujourd’hui au Musée du Louvre (Musée national du Louvre, 1878), 9.

[36] Louis Tuetey, Procès-verbaux, 111–3.

[37] AN F13/962 and F13/967, transcribed and discussed in Erlande-Brandenburg and Kimpel, “La statuaire de Notre-Dame,” 213–66.

[38] On the parvis see: Gilbert, Description, 39-50.

[39] Winston, Notre-Dame, 115.

[40] Louis-Sébastien Mercier, Le Nouveau Paris, vol. 6 (Chez les principaux libraires, 1800), 75–7. Fleury (“Histoire d’un crime,” 20) warns that Mercier’s account should not be taken as factual. See also the discussion in Clay, Iconoclasm, 220.

[41] Mercier, Le Nouveau Paris, 77.

[42] Naginski, Sculpture, 26.

[43]On the symbolic connotations of odor, see Alain Corbin, The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination (Harvard University Press, 1986), 29–70; and Suzanne Glover Lindsay, “Mummies and Tombs: Turenne, Napoleon, and Death Ritual,” The Art Bulletin 82, no. 3 (2000): 476–502.

[44] “Purgeons le sol des patriotes / Par des rois encore infecté” Lebrun, “ODE PATRIOTIQUE sur les événemens de l’année 1792, depuis le 10 août jusqu’au 12 novembre, par le citoyen Lebrun.” Gazette nationale, ou le Moniteur universel (Paris), February 6, 1793, 172.

[45]“Mais tandis que nous sommes en train d’effacer tous les vestiges de la royauté, comment se fait-il que la cendre impure de nos rois repose encore intacte dans la ci-devant abbaye de Saint-Denis?” Sylvain Maréchal, “De la fête des rois, de leurs tombeaux à Saint-Denis, et de leurs cœurs au Val-de-Grâce,” in Révolutions de Paris, dédiées à la Nation, no. 182, vol. 15 (1793), 83. See also the discussion of these excerpts in Réau, Histoire du vandalisme, 224–9.

[46]Allan Potofsky, “Recycling the City: Paris, 1760s–1800,” in The Afterlife of Used Things: Recycling in the Long Eighteenth Century, ed. Ariane Fennetaux, Amélie Junqua, and Sophie Vasset (Routledge, 2015), 71–88; Antoine Picon, French Architects and Engineers in the Age of Enlightenment (Cambridge University Press, 1992), 187–97; Richard A. Etlin, The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris (MIT Press, 1984).

[47] Pierre-Denis Boudriot, “Essai sur l’ordure en milieu urbain à l’époque pré-industrielle: boues, immondices et gadoue à Paris au XVIIIe siècle,” Histoire, économie et société 5, no. 4 (1986): 516.

[48] Potofsky, “Recycling the City,” 72; Boudriot, “Essai sur l’ordure,” 516.

[49] Léon Bernard, The Emerging City: Paris in the Age of Louis XIV (Duke University Press, 1970), 30. See also the discussion in Alan Williams, The Police of Paris, 1718–1789 (Louisiana State University Press, 1979), 26.

[50] Potofsky, “Recycling the City,” 82

[51] AN F13/503, fol. 593: “Enlèvement des décombres et pièces de vin qui encombraient l’église Notre-Dame lors de sa restitution au culte.”

[52] Clay, Iconoclasm, 264–7.

[53] Michel Fleury, “Comment la façade de Notre-Dame retrouve une partie de ses sculptures,” Archéologia 108 (July 1977): 20–35, 29–32.

[54] Werner Szambien, “Les architectes parisiens à l’époque révolutionnaire,” Revue de l’Art 83, no. 1 (1989): 36–50.

[55] Fleury, “Comment la façade,” 29–32.

[56] Archives de Paris, DQ10/755.

[57] The notice invited readers to visit his nearby shop for advice and samples from the Lorraine quarries at Remiremont, suggesting that Petit-Radel used ecclesiastical projects not only to establish his professional credentials but also to promote his commercial enterprise (Journal de Paris, no. 233 [August 14, 1777]).

[58] Archives de Paris, DQ10/755.

[59] Archives de Paris, DQ10/755.

[60] Archives de Paris, DQ10/755; Fleury, “Comment la façade,” 29–32.

[61] Adolphe Lance, Dictionnaire des architectes français, vol. 2 (Paris, 1872), 201–2; Louis-François Petit-Radel, “Destruction d’une église, style gothique, par le moyen du feu,” entry in Explication des ouvrages de peinture et dessins, sculpture, architecture et gravure des artistes vivans… (Livret) (Paris, 1800), 82.

[62] Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus, “Actes de vandalisme,” Annales archéologiques, ed. Didron Aîné (Paris, 1845), 3: 291–3.

[63] His name was also linked to one of the more macabre episodes of revolutionary desecration: in 1793, he was charged with dispersing the embalmed hearts of the Bourbons and was rumored to have offered the remains to painters as a substitute for the pigment “mummie,” derived from desiccated organic matter (Le Figaro 58, no. 42 [February 11, 1912], Georges Cain, “Dans les caveaux de Saint-Denis”).

[64]“La démolition de cette église a été effectuée en vertu d’une décision du ministre des Finances du sept Pluviôse an cinq, provoquée par le bureau central du canton de Paris, justement alarmé de l’état de dégradation dans lequel elle se trouvait et du péril imminent auquel sa conservation aurait exposé les citoyens.” AN F/2(II)/Seine/3, dossier 24 an VIII, Saint-Jean-en-Grève (église), démolition.

[65] Archives de Paris, DQ10/1390.

[66] Archives de Paris, DQ10/755.

[67]“On n’a fait aucune réparation depuis neuf ans, excepté celle de la couverture et de la vitrerie, qui sont maintenant en bon état. Les surdites dégradations menacent la sûreté publique et la conservation de cet édifice. Elles sont très urgentes.” Archives de Paris, DQ10/755.

[68] Aubert and Vitry, Le Cathedrale, 30.

[69] “Occasionnerait de grands malheurs.” Archives de Paris, DQ10/755.

[70] “Le démontage ne coûterait rien au moyen de l’abandon de ladite sapine et des fers qui y tiennent.” Archives de Paris, DQ10/755.

[71] Archives de Paris, DQ10/755, devis no. 2, 15 Fructidor an V.

[72] Fennetaux, Junqua, and Vasset, “The Many Lives of Recycling,” 2

[73] Williams, The Police of Paris, 270–71; Boudriot, “Essai sur l’ordure,” 520.

[74] Boudriot, “Essai sur l’ordure,” 518.

[75] Potofsky, “Recycling the City,” 82.

[76] Potofsky, Constructing Paris, 152.

[77] Potofsky, Constructing Paris, 150–56.

[78]Allan Potofsky examines the formation of this body within his broader study of the organization of the building trades in the late eighteenth century (Constructing Paris, 43–7). On the juridical dimensions of the topic, see Robert Carvais, “Le statut juridique de l’entrepreneur du bâtiment dans la France moderne,” Revue historique de droit français et étranger 74, no. 2 (1996): 221–52.

[79] Robert Carvais, “Quand les architectes jugeaient leurs pairs, les juristes représentaient-ils encore le droit des bâtiments?,” Droit et Ville 76, no. 2 (2013): 69–87. Nicolas Lemas echoes this view in “‘The Plaster Men’: Contribution to the Study of the Body of Parisian Expert-Jurors on the Fact of Buildings in the 18th Century,” Mémoires de la Fédération des Sociétés historiques et archéologiques de Paris et de l’Île-de-France 54 (2003): 93–148.

[80] See, for example, Journault, Almanach des bastimens… (Paris, 1776), 5; and Nicolas Lemas, “Les ‘pages jaunes’ du bâtiment au XVIIIe siècle,” Histoire urbaine 12, no. 1 (2005): 175–82.

[81] Archives Nationales, séries Z/1j. Petit-Radel’s name appears frequently in the repertoires Z/1j/1239–41 and in the corresponding procès-verbaux. His activity intensified after 1787. There are no entries under his name for the years 1783–1785, probably owing to the incompatibility of the status of expert-architecte-bourgeois with that of entrepreneur. See Potofsky, Constructing Paris, 51–7.

[82] Potofsky, “Recycling the City,” 83.

[83] Alexandre Tuetey, “Un projet de transfert du Musée des monuments français à Notre-Dame,” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français, 128–39.

[84] Alexandre Tuetey, “Un projet de transfert,” 136–38.

[85] d’Estaing, “Les rois retrouvés”; Fleury, “Comment la façade”; Gómez-Moreno, Sculpture from Notre-Dame.

[86] Over the following days, twelfth-century jamb statues from the Sainte-Anne portal, heads from the Portal of the Virgin, and numerous sculptural and architectural elements from the church were unearthed alongside them. Fleury, “Comment la façade,” 20.

[87] Fleury, “Comment la façade,” 20.

[88] Gómez-Moreno, Sculpture from Notre-Dame, 6.

[89] Among others, see Carmen Gómez-Moreno, Sculpture from Notre-Dame, Paris: A Dramatic Discovery (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979); d’Estaing, Fleury, and Erlande-Brandenburg, in Archéologia, no. 108 (July 1977): 6–51; Les Rois retrouvés; Peter Kurmann, “Die neuentdeckten Skulpturen von Notre-Dame in Paris,” Neue Zürcher Zeitung, July 1, 1977; Willibald Sauerländer, “Zu den neu gefundenen Fragmenten von Notre-Dame,” Kunstchronik (July 1977): 297–302; and Michel Fleury, “Sculptures de Notre-Dame,” L’Œil, no. 275 (June 1978): 18–23.

[90] d’Estaing, “Les Rois Retrouvés,” 623; and Gómez-Moreno, Sculpture from Notre-Dame.

[91] Fleury, “Comment la façade,” 32–4; d’Estaing, “Heurs et malheurs des rois de Notre-Dame,” in Les Rois retrouvés (Joël Cuenot, 1977), 8.

[92] Fleury, “Comment la façade,” 28; Potofsky, “Recycling the City,” 83–84. On Palloy, see also Maarten Delbeke, “Architecture’s Print Complex: Palloy’s Bastille and the Death of Architecture,” in The Printed and the Built: Architecture, Print Culture, and Public Debate in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Mari Hvattum and Anne Hultzsch (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2018), 73–96.

[93] d’Estaing, “Heurs et malheurs,” 8; Clay, Iconoclasm, 220–21.

Cite this article as: Demetra Vogiatzaki, “Economies of Waste: Revolutionary Administration and the Afterlives of the Notre-Dame Kings,” Journal18, Issue 20 Clean (Fall 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7995.

Licence: CC BY-NCJournal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.