Laura Golobish

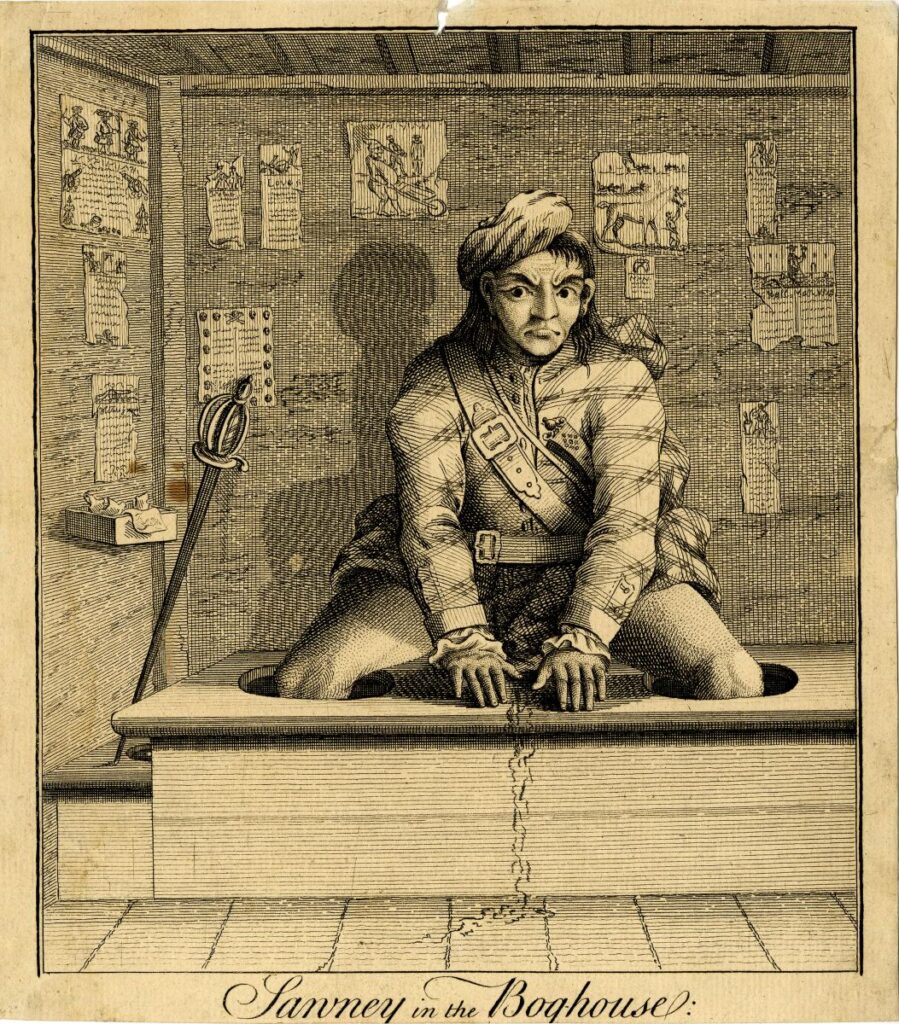

Urine spills onto the floor. A grimacing man stares out at you while seated with legs inserted into the vent holes of a public latrine (Fig. 1). Charles Mosley etched and published the visceral Sawney in the Bog-house on June 17, 1745, in a London workshop amid news of increased Scottish desertions of the British Army and rumblings of another Jacobite Rising against Georgian rule of Great Britain. This unflattering view presents the tartan-clad Scot misusing the toilet as someone requiring intense scrutiny with no corrective aid or recourse other than ridicule in the image and subsequent verse.

Sawney’s precarious position on the pot holds a multifaceted historiography. The name originates in sensational narratives about a sixteenth-century Scottish murderer and cannibal that continued to be mentioned into the eighteenth century. References were frequently reprinted in broadside ballads in which Sawney is noted for dueling, murder, and other mayhem.[1] Scholars regularly inventory Sawney in the Bog-house alongside subsequent adaptations of the print and other derogatory images of eighteenth-century Scots, particularly politicians.[2] Mosley’s set dressing of tattered prints adorning the wall has provided an opportunity to examine the breadth of genres used as bum fodder.[3] Further, Mark Jenner has positioned the print as an extension of civic infrastructure that conceals and monitors bodily waste and criminalized activities such as murder and public fornication.[4] Sawney thus sits at a nexus of ridicule, sanitation, and regulation of public space.

Despite the extensive interest it has generated, this etching is rarely placed within discussions of Scotland’s changing topography, mapping, or travel in the long eighteenth century. Scottish migration in caricature of the period takes multiple forms including transportation on foot, by wagon, and by carriage. It also extends to more ephemeral paths of dirt, disease, excrement, and poison. London caricaturists, in particular, began to attack Scotswomen’s alleged toxicity and hygiene as imminent threats to Great Britain’s political stability during the 1745–46 Jacobite campaign to overthrow Hanoverian rule. In these prints, Scottish ladies ply their craft as poisoners on behalf of Stuart princes, while riverside laundresses prevent the English from properly occupying the Scottish landscape. These are all physical actions, but the caricature and the periodical press framed Scotland and particularly Scottish travelers as an invasion or infection of Anglo-British character. I aim to extend the current discourse around caricature by thinking about how the language of hygiene and travel embodies the Anglo-Scottish border.

We live in a moment of questioning, reinforcing, or altering national borders. In autumn of 2020, Britain’s government botched the deployment of its COVID-19 testing program, in which the auto-scheduler sent people from southern England to appointments in Edinburgh and Perth, Scotland. On September 9, 2020, The Guardian published a cartoon by English illustrator Steve Bell featuring former Prime Minister Boris Johnson as an ass rappelling through greenery with text imploring readers to get a COVID test and see “unexplored Britain.” A subsequent image represents Johnson and his supporters in space suits posing in front of COVID-19 virions scaled to the size of planets, suggesting the distance rivals that of interplanetary travel.[5] At the same time, Glaswegian illustrator Lorna Miller depicted Johnson on a screen viewed through the portal of a cracking rocket ship yelling at his chief advisor Dominic Cumming for landing on the wrong planet.[6] Bell and Miller effectively highlight Johnson’s incompetence and position Scotland as an ideological frontier unknown by any entity south of its border.

As is often the fate of caricature, the image was buried by the relentless news cycle. The beginning of the pandemic has been historized, the National Museum of Scotland recently curating an exhibition on the local and international work necessary to develop and deploy the COVID-19 vaccines.[7] Five years have lapsed since the United Kingdom’s official exit from the European Union, and eleven since Scotland’s failed independence referendum. Former members of the European Parliament recently presented in Brussels to bolster support for Scotland’s future case to rejoin the European Union.[8] Meanwhile, the UK Parliament continues to highlight record deportation figures. A border-security bill, designed to make it more challenging for undocumented immigrants to gain paths to residency and citizenship, is currently under committee consideration in the House of Lords.[9] These fracturing borders provide a valuable vantage point to consider how the verbal and visual syntax of Scotland formed in the period following the establishment of the British state.

In the years preceding the publication of Mosley’s 1745 etching, English observations of Scotland extended beyond the confines of incorrect hygiene or behaviors not meeting expectations of national manners. In 1688, William of Orange landed in Brixham with 14,000 troops. Soon afterward, his father-in-law James VII of Scotland and II of England went into exile, and Parliament declared William and Mary II King and Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland. In 1689, James’s allies mustered a small army to attempt to restore him to the throne. John Dalrymple, Lord Advocate and later joint Secretary of State, agreed to offer financial compensation to be collected by Jacobite clan chiefs, in exchange for their signing an oath of allegiance before government witnesses, and to redirect resources to an alliance with the Dutch Republic, Bavaria, Brandenburg, Saxony, the Spanish Hapsburgs, and the Holy Roman Empire against France. Failure to make a properly observed and filed oath precipitated the massacre of the Glencoe MacDonalds in February 1692.

A series of changes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries brought new attention to Scottish land. Around 1609, James VI of Scotland facilitated the colonization of Ulster in Ireland following the Nine Years’ War, which forced many Gaelic people from Ireland to mainland Europe.[10] Throughout the 1690s and again in 1709, Scotland experienced widespread crop failure leading to famine and economic instability, which contributed in part to the failure of Scotland’s Darién scheme, an attempt to colonize Panama.[11] After the 1707 Acts of Union, insufficient agricultural production placed Scotland at a political disadvantage: it was unable to contribute resources initially under Queen Anne and then under George I, as they sought to expand British control of North America and the Caribbean against French and Spanish opposition.[12] Famine and Scotland’s political reorganization within Britain ultimately emphasized Scotland as an economic hub supporting the British Empire.

The Jacobites rose again after the 1714 succession of George I. In September 1715, John Erskine, Earl of Mar, traveled from London to Aberdeenshire to hold a war council and raise the Stuart Standard in support of James II’s son, James Francis Edward Stuart. By October 1715, Erskine had amassed an army of about 20,000 soldiers and controlled much of Scotland north of Edinburgh. A lack of accurate maps and information about Scotland’s topography hindered the British Army’s understanding of Scotland’s terrain and its ability to quickly quell any burgeoning rebellion. To prevent future uprisings, the British military invested in the production of new images, including maps, topographic drawings, and painted landscape views, and expanded Scotland’s roads and military fortifications.[13] Scotland and Anglo-Scottish political relationships were enmeshed with the project of mapping and shaping the topography for clearer navigation.

Regional newspapers began publishing weekly and monthly notices on Jacobite activities in early 1745. For example, on January 17, 1745, The Derby Mercury reported on news from Edinburgh dated January 10:

The Right Hon. the Earl of Crawford is expected over with the Hessian troops. The Rebels [Jacobites] have got possession of the town of Stirling. A very insolent message was sent to General Blakeney, inquiring him to deliver up the castle. They have been firing on that Fort, but at too great distance to do any execution. It is not doubted but it will hold out till the Forces march to its relief. . .Sixteen deserters from the British Regiments. . .were discover’d at Berwick by the Regiments to which they belong’d, are brought to town and will probably suffer death.[14]

This notice underscores both the domestic and international dimensions of the Jacobite rising, pointing to the ground the Jacobite army had taken, the consequences Scots faced for deserting the British Army, and the efforts Scottish supporters of Georgian rule, such as the Earl of Crawford, were willing to go to suppress the rebellion by hiring Hessian mercenaries. The same issue’s coverage of France also notes aid from the Paris court for the Jacobite cause and for Prince Charles Edward Stuart. These reports highlight how Scotland, and especially its martial bodies, charted a multi-regional information network.

Entrenched in this context, Mosley published Sawney in the Bog-House. The inscription below the intimate scene of a figure mid-ablutions highlights a curious incident in which someone directs Sawney to the outhouse and watches as the Scotsman examines the space and inserts his legs into the latrine’s holes:

To London from his birth,

Had dropt his folio cates on Mother Earth;

Shewn to a boghouse, gaz’d with wondering eyes,

Then, down each venthole, thrust his brawny thighs;

And squeezing cry’d “Sawney’s a laird. I trow,”

Neer did he naably disembaage ‘till now.

This verse goes beyond merely confirming an error in using the facilities. It describes the figure’s muscular thighs and the zest with which he makes a mess of himself in the vent holes while warbling that he is now a laird of an estate from his new station in a public outhouse. Sawney’s knowledge and self-assurance are distinguished from the English lexicon with the Scots word trow (or trew), meaning “to believe” or “to know.” Sawney is not merely being denigrated or made fun of; rather he is put on display to be examined for his differences in appearance and language by viewers in London, where he has traveled and where the etching originated.

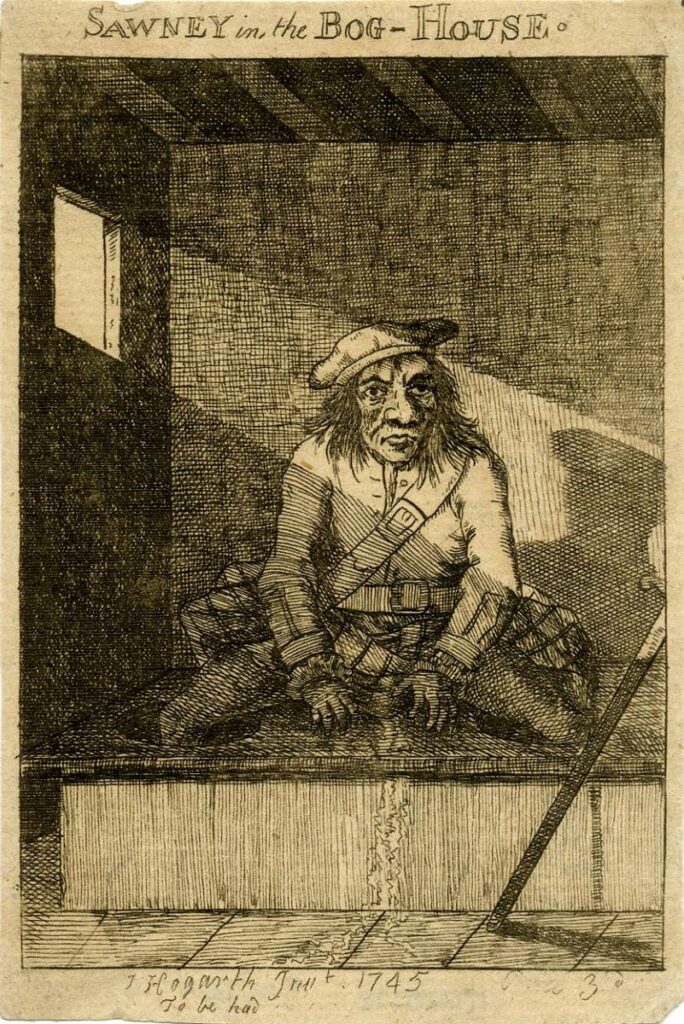

In the weeks following Mosley’s initial publication, the Jacobites raised the Stuart Standard in Scotland, visually marking the start of the 1745 Jacobite rising led by Prince Charles Edward Stuart. Numerous artists copied Mosley’s image during this period. The differences between one anonymous copy and the original composition are telling (Fig. 2). This copy features a window with a wide beam highlighting Sawney’s face and an enlarged stream of urine against a sparse, dimly lit background, unlike the even lighting across an array of broadsides displayed on the wall in Mosley’s print. The caricature and the political climate of mid-eighteenth-century Britain direct the viewer to think about Scotland along with the appearance and behavior of Scots.

The text on Mosley’s print points to further geographic connections beyond travel to the London metropolis. The last phrase of the inscription reads: “Neer did he [Sawney] naably disembaage ’till now.” The verb “disembogue,” styled to give the effect of a dense Scottish accent, refers to the opening or mouth of one body of water connecting to a larger one. Here, the noble disemboguing points to Sawney’s stream of urine covering the seat and floor of the privy and the collected excrement in the vault under the seat. Sawney’s act of urination and disemboguing charts the topography of his body and maps the paths from Scotland to England.

Pierre-Charles Canot, a French engraver then based in London, also etched Scotch Female Gallantry during the 1745–46 Jacobite campaign (Fig. 3). Often overshadowed by the visceral nature of Mosley’s print, the work features a group of women adorned in richly colored gowns swarming around Prince Charles Edward Stuart. Canot, who was elected as Associate Engraver to the Royal Academy in 1770, frequently designed and engraved pastoral and picturesque landscapes. However, the printer’s work rarely extended to Scottish motifs. His atypical focus here on the Scottish female body underscores the overarching public interest in Scots and their character during the period. The bedroom features the portraits of Charles Edward’s parents. Figures at the edge of the group point toward the prince while two women kiss his hands and another, in a yellow gown, grasps Charles Edward’s sash and kisses it. This dramatic performance of affection by the crowd draws attention to the prince’s popularity.

The inscription paired with the image lends a more nefarious tone to the chaotic composition:

To Edinburgh Charley came,

And set the Scottish Nymphs on Flame

Each the tall starring youth admir’d,

And tip-do’d to his—Lips aspir’d

Susannah of romantic size

First form his Eye-lid snatch’d a Prize

Next Marg’ry with a Spring arose,

And stole a favour from his Nose,

Then Nancy ran, in Stature low’r

And froth’d his gaudy Ribband o’er. . .

The text accentuates the speed and aggression of the women’s actions. They snatch, spring, steal, and froth. In later stanzas, they believe this pilgrimage is holier than kissing the Pope’s feet. They are portrayed as foolishly misjudging the prince’s importance and his poor choice of accessories. They also pose a great threat. The verse continues:

But while these foolish Females take

And to their Bosoms clasp the snake

Let English Nymphs the Pest beware

For poison lurks in Secret there. . .

Scotswomen who can interact directly with the prince serve as a layer of protection against non-Jacobites and the British government. In doing so, Scottish women threaten English character—especially that of English women—without ever leaving Scotland, whereas the masculine Sawney is most dangerous for physically traveling to London.

Mapping the Scotch Fiddle

Scottish topography withstood further changes after the military and legal suppression of the 1745 rising. Politicians began to encourage and enforce the restructuring or improvement of Scottish estates and common grazing lands. Large numbers of crofters were evicted and pushed from the Highlands into coastal towns, cities, and British colonies; several estates were foreclosed and changed ownership; thousands of acres of land in the Lowlands and Highlands were enclosed to increase agricultural yields and property values.[15] Further, many writers touted Scottish participation in this new agricultural system within Britain and in foreign colonies as a corrective measure for perceived ill temperament and other negative qualities imbued upon Scots.[16] Enclosure radically changed the appearance of Scotland’s topography and the organization of its population.

Enclosure, along with regulations on Scots language, dress, and other cultural practices, assimilated Scotland into the political, economic, and social structures of the British Empire to great effect. Mirroring the paths presented in prints of satirized Scottish character types, several prominent anti-Jacobite Scottish figures, such as John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, moved to London during the 1740s. Bute rapidly rose in power, from royal tutor to member of the Privy Council and Secretary of State for the Northern Department.[17] Bute’s prominence made him a specific target for caricaturists and other critics beyond the confines of the slovenly and ignorant character type of Sawney or unnamed aristocratic women.

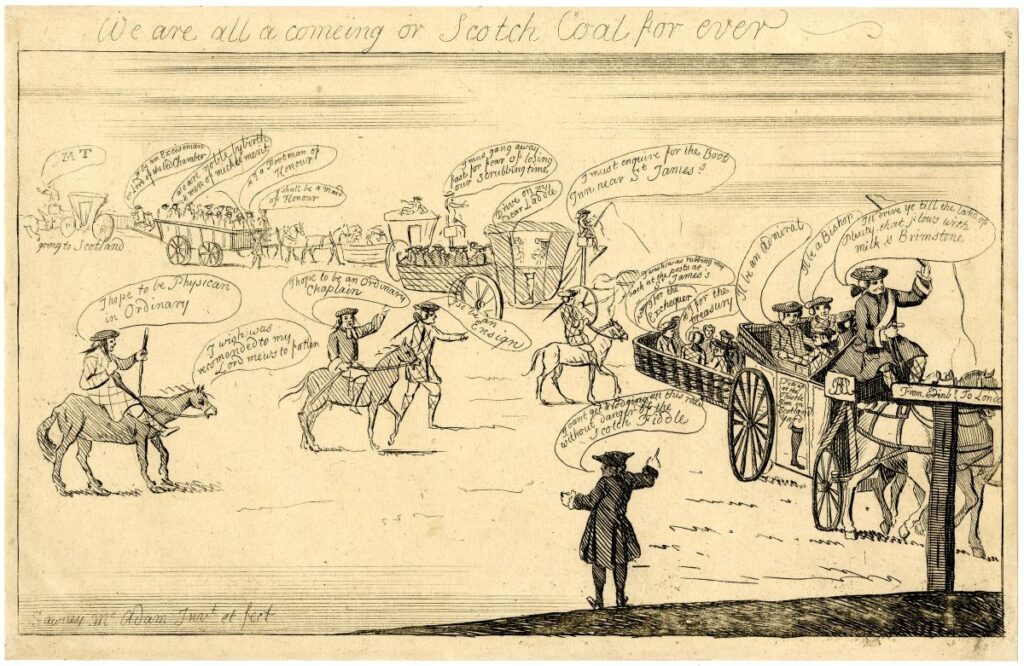

Caricatures of Bute envisioned his direct impact on British territory. During the Seven Years’ War, English politicians continually attacked Bute’s leadership as Secretary of State and later as Prime Minister. In 1761, an anonymous artist designed We are all a comeing or Scotch Coal forever (Fig. 4). Here, a line of crowded wagons and coaches along with three men on horseback follow a road with a sign pointing to London. Bute drives the front carriage on the path to London and exclaims, “I’ll drive ya to the land of plenty that flows with milk and brimstone,” while other miscellaneous tartan-clad figures scattered throughout the frame announce vocations they will be appointed to in their destination. Working in London with the prominent publisher Mary Darly, the unidentified caricaturist appears to be in on this plan. The pseudonym “Sawney McAdam” mirrors that of the Scottish character type from earlier prints and does not match any currently identified eighteenth-century printmaker. The naming convention positions the printmaker as one of the Scots following Bute to gain desired occupations in the metropolis.

Other details in the composition point to the consequences of this haphazard caravan of travelers encroaching on London. An onlooker in the immediate foreground comments that they are unable to “get lodgings on this road without danger of the Scotch Fiddle.” The phrase “Scotch Fiddle” refers to lice or scabies infestation and other maladies involving itching. Thus, according to the onlooker, Bute leads masses of louse-laden Scots to occupy space in London and make it less hygienic.

The Evacuations or An Emetic for Old England Glorys (1762) more viscerally stages how Bute affected British territory and character (Fig. 5). In the guise of an ass adorned in a kilt and thistle-embellished hat, Bute heads a line comprising his followers Scottish author Tobias Smollett and statesman Henry Fox. Bute blindfolds Britannia with a strip of tartan fabric while the personification vomits the names of British conquests from the Seven Years’ Wars into a bowl. Smollett checks Britannia’s radial pulse. Lastly, Fox thrusts a giant enema syringe. The trio’s assault of Britannia results in her illness, rather than the more passive transmission of lice by proximity depicted in the previous caricature.

The inscription expands on the violent scene. The first stanza brands Bute a “Quack” who administers a “Scotch Pill” to England that results in the personification being “sick at heart,” and ultimately releasing her honor. A quack, also known as mountebank, traveled from area to area while staging performances to sell proprietary or patent medicines with negligible medical value. The listed “Scotch Pills” had been advertised since at least the seventeenth century for the purpose of inducing vomiting and defecation. In this case, the administration of such medication induces the release of Britannia’s digestive tract at the expense of her honor. Viewers then perceive the changes to Britannia’s incorporeal character traits through the textual construction of her body.

The labeled contents of Britannia’s vomit expand on Bute’s political relationships. Britain seized several North American and Caribbean territories during the war. As Prime Minister Bute began negotiating an end to hostilities with France and Spain in late 1762, he agreed to return many of those territories to their previous colonial rulers. His opposition viewed the release of these territories as proof of the prime minister’s weak character and Scotland’s infringement on English social standards.[18] Britain’s personified body forms a conduit from the emetic ministrations of masculine politicians into the nation to the larger network of the Empire. Britannia’s digestive ills materialize the filth and disease besmirching the entire nation’s character, much as Sawney’s stream of urine maps Scotland’s connection to the London metropolis.

The Burden of Maids and Laundresses

Artists and authors also turned their attention to the domestic labor of Scotswomen, alongside the assault on the personified Britannia. Acts of household cleaning took on the tone of spreading national filth. In The Flowers of Edinburgh (1781), a woman wearing a pristine dress, apron, and bonnet dumps a full slop bucket from a second-floor window in the course of regular household cleaning (Fig. 6). The excrement sluices over a trio of tartan-clad Scotsmen gathering in the street below. One of the men squats over an overflowing bucket to relieve himself while another yells that the woman should hold her hand and cease emptying her bucket. To the right, a man reclines near a pot under the stream of liquid. He’s hocking the liquid, at the rate of two dips of the ladle for pocket change. The Scotsmen are filthy and of dubious character, but the chambermaid’s work, and that of others like her, ultimately enables this behavior. Representations of household hygiene continue to map the boundaries of national filth.

An iteration of the Flowers of Edinburgh accompanied a 1781 adaptation of Allan Ramsay’s comedy The Gentle Shepherd (1725), partly translated from Scots to English and staged at London’s Drury Lane. The periodical press responded with mixed reviews, speaking to the pleasure it yielded for audiences of many classes and levels of taste, and to the barrier created by its language. For example, on October 6, 1781, The Morning Chronicle recountedthat the dramatist “took the pains to prepare the piece, and just so far modernize it, as to render the whole somewhat more generally intelligible, by anglicizing such of the phrases as were most obscure.” In that same month the Lloyd’s Evening Post observed that Allan Ramsay’s work could only previously be fully evaluated or enjoyed by an audience defined by the following qualities:

Those only whose knowledge of the Scottish dialect has enabled them to judge of its excellencies. That an English audience might become partakers of this entertainment, seems to have been the laudable design of the Dramatist in now divesting it of its numerous provincialities, grown almost obsolete even in Scotland, at this distant period.

These comments suggest that the play was wholly unintelligible to anyone without knowledge of Scots.[19] Because the distinct linguistic and iconographic elements representative of Scotland were cast as distant, provincial, and difficult to understand, the play had to be sufficiently homogenized to be simultaneously understood as Scottish and different while entertaining the Anglophone audience.

Linguistic difference thus forms a potent part of the growing imagined paths of potential filth and infection. The filth doesn’t only sit in the maid’s chamber pot or the shit stewing in the cauldron represented in Flowers of Edinburgh; within this context, the excrement is mirrored in commands shouted in Scots at the silent woman or at prospective buyers of suspicious stew. One of the men demands that the young woman “Haud your hond lassie,” rather than the Fleet Street printshop anglicizing it as “Hold your hand,” or another iteration of “stop.” The would-be salesman hawks his wares in Scots with “Twa dips & a wallop for a Baubee,” rather than translating for the audience as “Two dips for a halfpenny,” or Scottish sixpence. The choice to maintain Scots selectively spreads the dirt through London much like the chambermaid flooding the street with excrement.

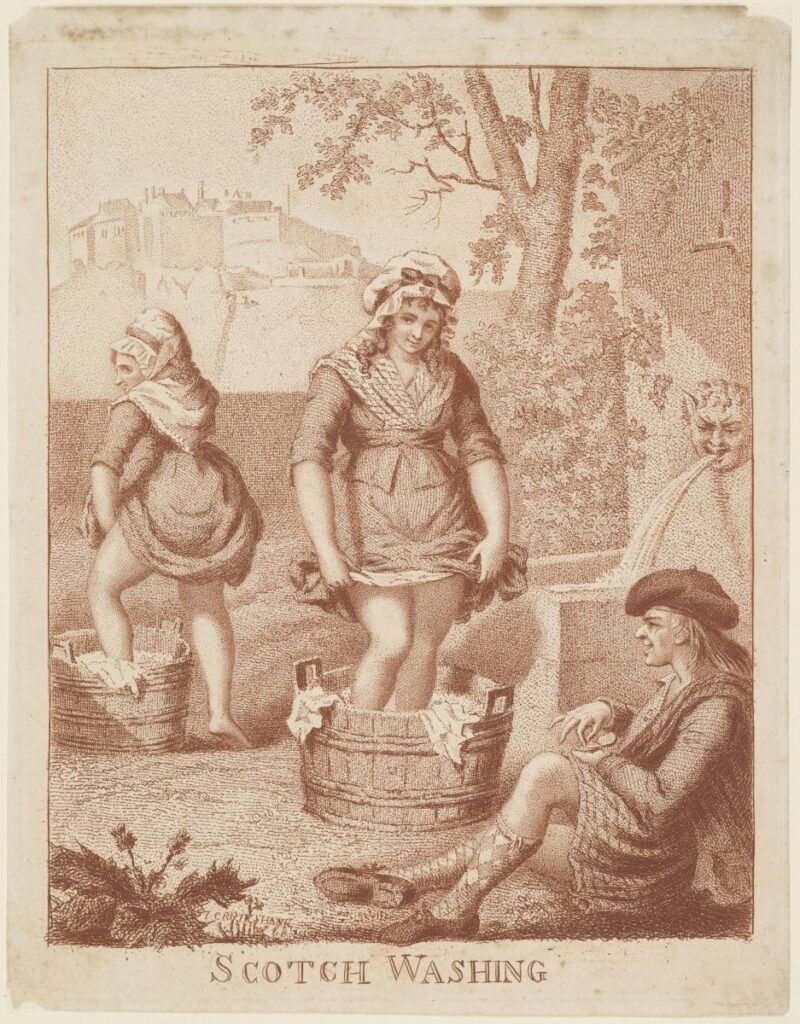

Scottish laundresses also gained pictorial notoriety during the late Georgian period for the particular ways in which they failed to make messes. A survey of the collections from the National Galleries of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland reveals caricatures and eventually photographs of Scotswomen in scenes labeled “Scotch Washing,” which depict one or more women standing in a washtub and using their feet to agitate laundry near a river or in other outdoor settings. This iconography continues to convey a relationship between land and cleanliness. Moreover, the lack of visible dirt or blemishes on the women or the laundry in their care prompts consideration of what borders may be crossed.

Scottish-born and London-based printmaker and illustrator Isaac Cruikshank issued his first iteration of Scotch Washing in approximately 1785, around the time of his move from Scotland to England (Fig. 7). In this stipple engraving, two women heave their skirts high above the knee while treading on laundry in wooden tubs filled from a grotesque fountainhead. Edinburgh Castle forms the background. A tartan-clad man, propped against a cracked wall, observes. Little about the women identifies them as Scottish, save the central figure’s shawl featuring a light plaid or tartan. Rather, the landscape, architecture, and ogling man imbue those characteristics. Feminine labor and hygiene are enmeshed to create the idea of laundry that is specifically Scottish.

Skilled workers, such as laundresses, were essential to the maintenance of the household.[20] In Great Britain, this manner of laundering was particularly identified as Scottish. This distinction first appears in a published set of letters written by Edmund Burt that were reprinted and referenced by subsequent authors and tour guides over the next century. The author remarked, in 1754:

Before I leave the Bridge, I shall take Notice of one Thing more, which is commonly to be seen by the sides of the River (and not only here, but in all Parts of Scotland where I have been), that is, Women with their Coats tucked up, stamping, in Tubs, upon Linen by this Way of Washing; and not only in Summer, but in the hardest frosty Weather, when their Legs and Feet are almost literally as red as Blood with the Cold; and often two of these Wenches stamp in one Tub. . . .

But what seems to me yet stranger is, as I have been assured by an English Gentlewoman, that they have insisted with her to have the Liberty of washing at the River; and, as People pass, by, they divert themselves by talking very freely to them, like our Codders, and other Women, employed in the Fields and Gardens about London.[21]

The author then persists, outlining other household tasks Scotswomen completed with their feet. He describes how they use a rag to clean floors with their feet rather than a mop, noting that he even had a mop made for the workers at the inn where he stayed and taught them how to use the new tool.[22] The localized work habits that Burt claims to have noticed in all parts of Scotland are strange or otherwise at odds with his Anglocentric expectations. As such, the boundaries of Scottish laundry connote incorrect household management and poor hygiene.

This brief section of Burt’s letter underscores the visual prominence of laundresses. They work year-round in this manner of washing by the river, to the apparent detriment to their circulatory systems and flushing skin. They talk to passersby while they work, and they actively assert the right to complete the task on site rather than hauling water away from the river. Women represented in the act of “Scotch Washing” unabashedly fill and engage space with their essential labor.

Burt also highlights their difference in social station. In particular, he notes in passing the likeness of Scottish laundresses to English cotters or codders who leased their farm and garden plots from an estate owner. He names them by occupation, whereas he refers to the laundresses with the typically derogatory term “Wench” that applied to working women in occupations ranging from prostitution to domestic service. The laundresses secure permission from an English gentlewoman of a nearby estate to complete the task on site rather than hauling water away from the river. Laundresses and scenes of “Scotch Washing” thus represent a nuanced intersection of class, gender, and the politicized landscape.

A cast of laundresses that Cruikshank printed a few decades after his establishment in London further emphasizes the wide differences between Scottish womanhood and hygienic propriety. A Bucking Washing on Tweeside (c. 1805) forgoes the sedate contrapposto of Cruikshank’s earlier Scotch Washing with two women stomping in the washtub with a wide stance (Fig. 8). They have precariously cinched their plaid skirts to the apex of their thighs. One bares her breasts. A man, tucked stealthily behind a tree, leers up. The women mark the space as indecorously Scottish, and, perhaps more importantly, as not English.

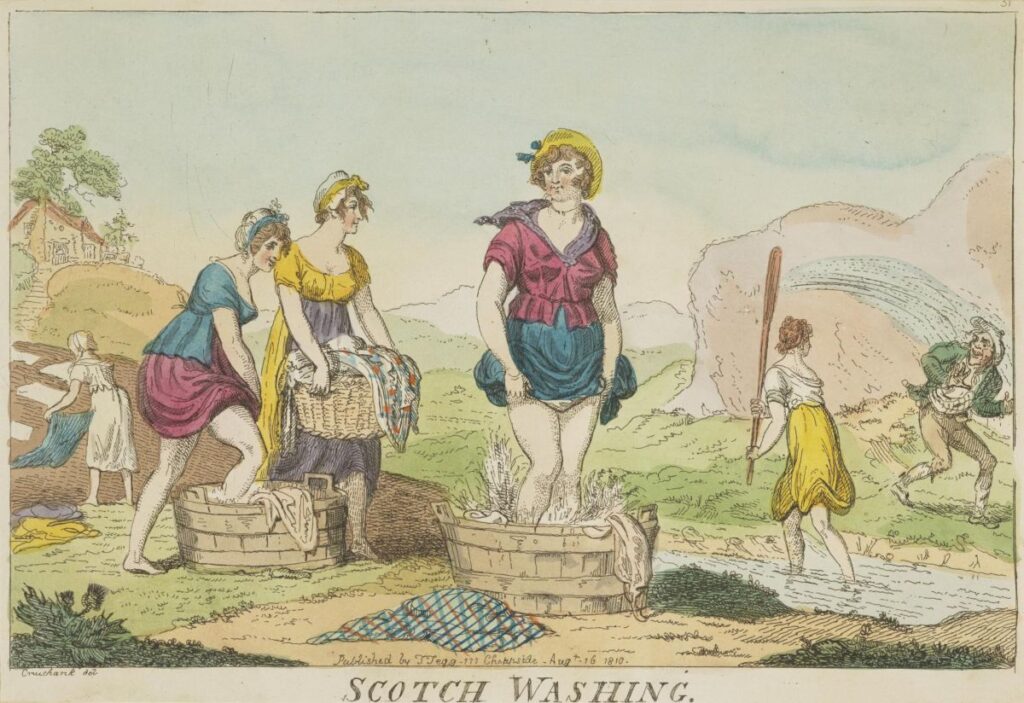

The scenery in this later print is also somewhat ambiguous. It is vaguely reminiscent of the Tweed Water along the Anglo-Scottish border, but it also bears similarity to numerous other landscape views available at the time. Isaac’s son George Cruikshank featured a similarly ambiguous landscape in his Scotch Washing (1810) without any geographic labeling in the title to hint at location (Fig. 9). Here, the laundresses are not adorned in tartan as in A Bucking Washing. They stomp in their tub and lay out linens to dry on the bank, while one woman bravely fends off an encroaching Scotsman in a plaid sash with the swift, arching motion of her washing paddle. The combined gesture of cleaning and unabashedly occupying space signals nationhood and makes visible the border without the microscopic aid of bugs and quack medicine.

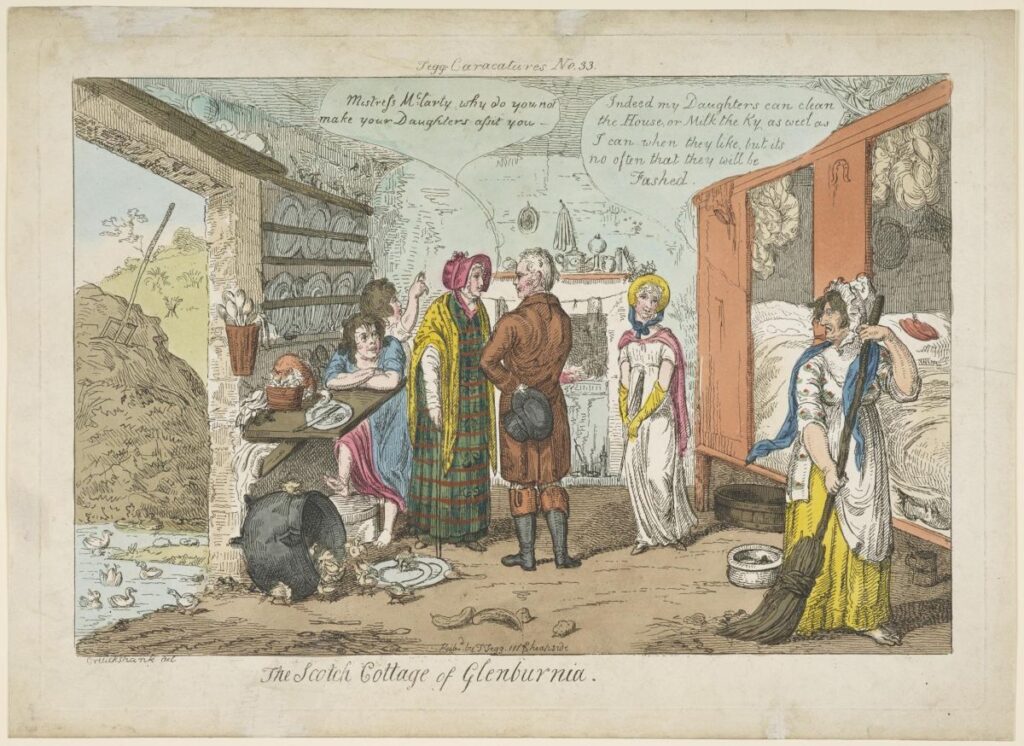

Cruikshank also suggests the consequences of living without women’s hygienic guidance. Chaos emerges in The Scotch Cottage of Glenburnia (1810) with groupings of figures in a visual standoff amid the mess (Fig. 10). The man wearing a brown coat stares at two barefoot children in blue and white dresses; the woman in a tartan day dress stares at a young woman draped in cream dress and yellow gloves. Finally, the young woman frozen in a stiff contrapposto stares at the elderly woman laboring in the right corner. Her pristine dress would have required a rigorous laundry routine to maintain in such an environment, and her passive posture suggests that she is not the one doing that work.

The early nineteenth century brought new literary attention to Scotland. Leisure travelers began to flock to the country to see the region that Walter Scott so picturesquely described in his poem Lady of the Lake (1810). Scottish novelists turned their attention to Scottish domestic spaces alongside Scott’s epic poetry. Elizabeth Hamilton’s Cottagers of Glenburnie (1808), Mary Brunton’s Discipline (1814), and Susan Ferrier’s Marriage (1818) all construct the character of Scottish women and the ideals of Scottish domestic life and economy through comparisons to the boundaries of English mannerisms.[23] The Cottagers of Glenburnie, which Cruikshank references in Scotch Cottage of Glenburnia, concerns the widowed Mrs. Mason’s return to Scotland to be the housekeeper for the MacClarty family, whose surname literally labels them as dirty or muddy. Mrs. Mason’s efforts to reform the family’s filth and poor economy result in changes to the character of the town’s denizens, which are complemented by improvements to its material appearance.

Reviews of the first edition and dozens of editions from the next fifty years confirm the novel’s moral and didactic qualities. For example, in September 1808, The Scots Magazine said of the novel:

This little work, with its ingenious satire on certain parts of our national character, has excited an extraordinary sensation in this metropolis [Edinburgh]. The charges which it advances are such as we have been long accustomed to hear from our English neighbours, and have, through custom, become somewhat callous to. But this is the first time that the attack has been made by one of ourselves, and by one who appears to be intimately acquainted with all the penetralia of our household economy. When so strong a part of the garrison is thus found co-operating with the enemy, there seems reason to apprehend that the fortress of national prejudice will not be long able to hold out.[24]

The review goes on to mention that inefficient household management impacts all residents and particularly how it leads to a weak and shameful indulgence of children. However, thanks to a novel, these poor behaviors have been largely eliminated in “the more cultivated parts of the country.” The review describes Scots in martial terms as a garrison of troops deployed in order to defend the border and character against insult from the English “neighbor,” and later “enemy.” However, when someone identified as Scottish corroborates this negative opinion, it is perhaps time to break rank and make the suggested changes. Landscape and hygiene habits are tightly enmeshed within the idea of boundaries defining national character.

London reviewers responded in a similar manner to the great improvements this book made possible for Scotland, but they also noted the sweeping accessibility of the novel’s content. The Literary Panorama announced in 1816 that The Cottagers of Glenburnie was

a lively, humorous picture of the slovenly habits, the indolent winna-be-fashed temper, the baneful content which prevails some of the lower class of the people of Scotland. It is a proof of the great merit of this book, that it has, in spite of the Scottish dialect with which it abounds, been universally read in England and Ireland, as well as in Scotland. It is a faithful representation of human nature in general, as well as of local manners and customs. . .In Ireland, in particular, the history of the Cottagers of Glenburnie has been read with peculiar avidity, and it has probably done as much good to the Irish as to the Scotch. [25]

Rather than dwelling on the similarities or collusion with the English, this critic emphasizes the novel’s appeal to a broad audience despite the specificity of the Scots language and local mannerisms. However, the text is most appealing to the Irish, who apparently read the story with “peculiar avidity,” resulting in high impacts on Irish land and character, perhaps due to the common history of Ireland rising against foreign rule that goes unmentioned in this review. The 1798 Irish Rebellion and subsequent 1800 and 1801 Acts of Union that combined Britain and Ireland in the United Kingdom stood as recent history at the 1808 publication of Hamilton’s novel. No extant reviews comment on the text being an influence on the improvement of English agriculture or manners. Hamilton’s novel provides a lens through which to observe and communicate the borders of national characteristics.

Likewise, Elizabeth Isabella Spence reported on the great debt that Scotland owed to Hamilton:

Poverty and dirt no longer excited disgust. The visible change for the better, is most grateful to the eye, and pleasant to the feelings in the progress of improvement. The neat cottages of the poor are now built of good substantial stone of the bounty, finished with slate, instead of thatched roofs, and sashed window, which admit the light of heaven. The dunghill before the door has disappeared, and rural gardens, with fruit-trees and flowers, embellish the walls. How greatly are the lower class indebted to Mrs. Hamilton, for the “Cottagers of Glenburnie” which has tended to effect such a happy change amongst that community of people, that must ensure not merely comfort, but health.[26]

For Spence, the impacts of progress in hygiene and manners created pleasant effects on the eye and feelings. Further, the novel inspired substantial improvements to infrastructure, with houses now being built with sturdy stone and slate, and an unsightly dunghill being replaced by orchards and gardens. The whole of these changes suggests that Scottish poverty is ennobled rather than disgusting when processed through the proper moral framework.

Returning to Cruikshank’s Scotch Cottage offers readers a moment to see how the maintenance or propagation of dirt visually operates in a domestic space. The statuesque young woman stares at her mother, the elderly woman sweeping in the lower right corner. The tartan-enrobed Mrs. Mason demands to know why Mrs. McClarty’s daughters do not help with the cleaning. Mrs. McClarty retorts, while sweeping the dirt floor and gazing toward the doorway, that they are capable, but they are not usually fashed, or bothered, to do so. A flock of ducklings swim in a puddle directly adjacent to the door and others wander into a kettle that’s tipped over on the ground. The view is blocked, but the male figure stares at the smaller children rather than the mess outside. Children and the labors of women ensure the perpetuity and financial wellness of the land and estate. The McClarty children cannot be bothered to perform the household chores and make the home a productive space. The filth and chaos threaten not only the home’s comfort, but also the view of a carefully framed and composed landscape. The unpictured end of Hamilton’s novel involves entirely restructuring the McClarty home and estate. This narrative template mirrors the country becoming more orderly and formulaic for visiting eyes to understand and occupy Scotland, much like earlier efforts to map and fortify the country.

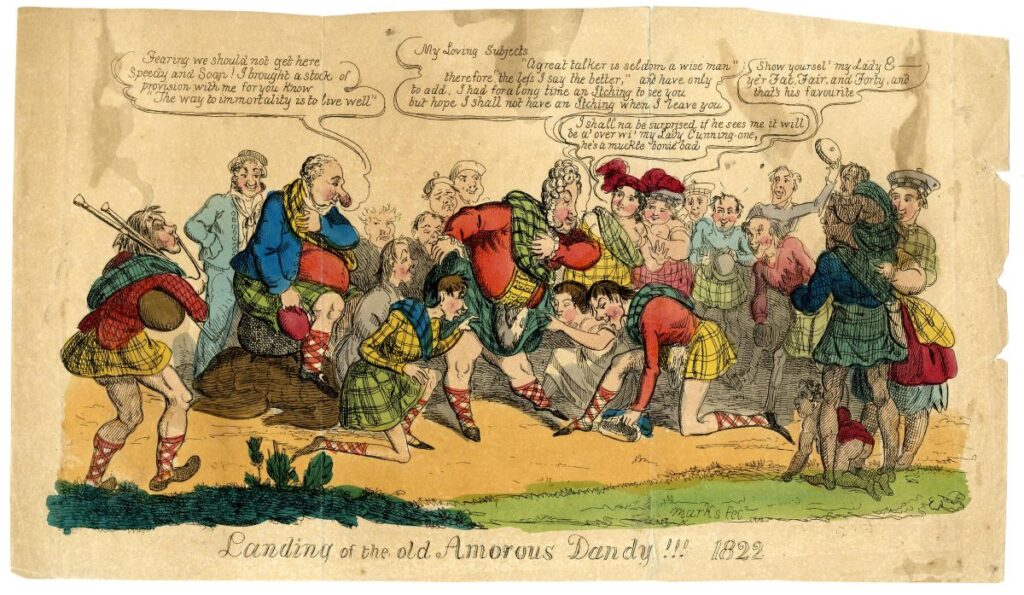

Tourism and travel literature supplanted much of the public language of surveillance surrounding Scotland as the nineteenth century progressed. However, caricatures of George IV highlighting connections with his mistresses during the 1822 Royal Progress to Edinburgh provide one last major avenue through which Scotswomen were branded as disease vectors. Landing of the old amourous dandy!!! displays a group that mirrors the crowd in the earlier Scotch Female Gallantry (Fig. 11). George IV, rather than Charles Edward Stuart, stands at the center of a clamoring audience in Scotland’s capital. He announces in the lettering that he “had for a long time an Itching to see you but hope I shall not have an Itching when I leave you.” Responding to the King’s presence, the woman in yellow and green tartan with partially exposed breasts notes: “I shall na be surprised if he sees me it will be a’ over wi’ my Lady Cunning-one, he’s a muckle bonnie lad.” Her companion retorts: “Show yoursel’ my Lady E[lphinstone] ye’r Fat, Fair, and Forty, and that’s his favourite.” The exchange implies that the King has an impulse or neurological itch to visit Scotland and particular residents. The woman wants the attention, and her companion offers support by noting that she possesses the King’s favorite qualities. The scenario implies that the King is currently louse-free and is hoping that his associations with favored Scottish women will not result in infestation.

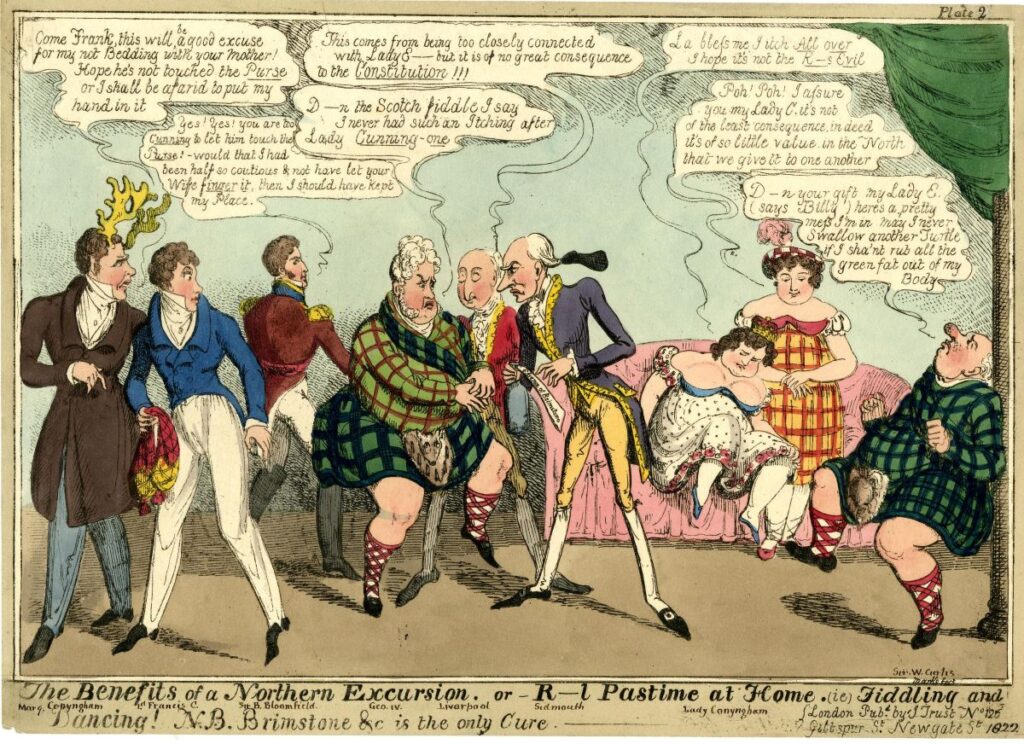

Lady Conyngham and Lady Janet Elphinstone, George IV’s English and Scottish mistresses, appear in several other caricatures relating to the Royal Progress. One in particular reprises the theme of itching. In The Benefits of a Northern Excursion (Fig. 12), we see how Conyngham possibly ends up with infection. On the saccharine pink sofa to the right, Conyngham scratches her posterior and ponders whether she has gotten the “King’s Evil” as their Scottish hostess, Elphinstone (in the red and yellow tartan) responds that the infection is of so little consequence that everyone passes it back and forth. Toward the print’s left side, the Home Secretary, Henry Addington, suggests that the King’s ailment stems from the close association with Elphinstone, and the King also announces, “Damn the Scotch fiddle I say I never had such an Itching after Lady Cunning-one.” The narrative thread implies that Elphinstone’s inappropriate behavior infected English women by way of the King rather than traveling directly to London. The King’s status reflects the status of the women he consorts with, and in consorting with diseased Scots, he marks Britain as morally corrupt. Women’s bodies again bear the cost of mapping the boundaries of difference.

Untangling the Laundry

Paths of excrement, illness, dirty laundry, and language from Scotland to England occupy a large space in Georgian caricatures about Scotland. Sawney and his comorbid colleagues trace a filthy trail from north to south and back again in London caricature. Those paths continue today in the testing of British borders, for example in Prime Minister Kier Starmer’s plan to “take back control” of the United Kingdom’s borders, at the expense of vulnerable immigrant communities, in addition to reducing Scottish access to health care.[27] This historic and ongoing pattern extends far beyond denigration. It speaks to Anglo-British investment in maintaining the subservience of Scotland’s people and resources. Unraveling these threads of maps, hygiene, and gendered labor establishes a vocabulary in which definitions of English character depend intrinsically on the boundaries of Scotland’s squalor.

Laura Golobish is Assistant Teaching Professor of Art History at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana

Thank you to Matt Gin, Susanne Anderson-Riedel, and the anonymous peer reviewers for feedback on early versions of this project. I also appreciate Michael Lorsung for sharing workshop space and coffee with me while I finished writing.

[1] Julie Gammon, “Retelling the Legend of Sawney Bean: Cannibalism in Eighteenth-Century England,” in To Feast on Us as Their Prey: Cannibalism and the Early Modern Atlantic (University of Arkansas Press, 2019), 135–52.

[2] Gordon Pentland,“‘We Speak for the Ready’: Images of Scots in Political Prints, 1707–1832,” Scottish Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2011): 64–95, https://doi.org/10.3366/shr.2011.0004 (all weblinks accessed October 27, 2025).

[3] Gillian Russell, “Making Collections: Enlightenment Ephemerology,” in The Ephemeral Eighteenth Century: Print, Sociability, and the Cultures of Collecting (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 80–85.

[4] Mark Jenner, “Sawney’s Seat: The Social Imaginary of the London Bog-House c. 1660-c.1800,” in Bellies, Bowels and Entrails in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Rebecca Anne Barr, Sylvie Kleiman-Lafonand, and Sophie Vasset (Manchester University Press, 2018), 71–3.

[5] Seve Bell, “Go for a Covid Test…,” The Guardian, September 9, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2020/sep/09/steve-bell-on-the-uks-world-beating-test-and-trace-system-cartoon; Steve Bell, “Moonshot,” The Guardian, September 10, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2020/sep/10/steve-bell-moonshot-testing-plan-cartoon.

[6] Lorna Miller, “UK Runs Out of Testing Capacity,” Bella Caledonia, September 17, 2020, https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2020/09/17/uk-runs-out-of-testing-capacity/.

[7] National Museum of Scotland, Injecting Hope: The Race for a COVID-19 Vaccine (2025), https://www.nms.ac.uk/past-exhibitions/injecting-hope.

[8] Steph Brawn, “Ex-MEPs head to Brussels to make Scotland’s case for rejoining the EU,” The National,April 7, 2025.

[9] UK Parliament, Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill, HL Bill 101 (2025), https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3929.

[10] For more on Scotland’s patterns of settler colonialism and migration, see Collin Woodard, “Founding Greater Appalachia,” in American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America (Viking, 2011); and David Hackett Fischer, “Borderlands to the Backcountry: The Flight from North Britain, 1717–1775,” in Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (Oxford University Press, 1989), 654–55.

[11] Eric Richards, “Darién and the Psychology of Scottish Adventurism in the 1690s,” in Imperial Expectations and Realities: El Dorados, Utopias and Dystopias, ed. Andrekos Varnava (Manchester University Press, 2015), 26–31.

[12]Alexander Charles Baille, Call of Empire: From the Highlands to Hindostan (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017), 9–10.

[13] Carolyn J. Anderson and Christopher Fleet, Scotland: Defending the Nation, Mapping the Military Landscape (Birlinn Limited), 80–92. See also John E. Crowley, Imperial Landscapes: Britain’s Global Visual Culture, 1745-1820 (Yale University Press, 2011).

[14] “Scotland,” The Derby Mercury 14, no. 44 (January 17, 1745): 2.

[15] Barbara Arneil, Domestic Colonies: The Turn Inward to Colony (Oxford University Press, 2017), 137–39.

[16] For examples, see “On Scottish Emigration To America, And Lord Selkirk’s Canadian Colony,” The Literary Magazine, and American Register 5, no. 33 (June 18, 1806): 446–57; Alexander Irvine, “Causes Of Emigration from the Highlands,” The Scots Magazine 65 (April 1803): 267–69; A Constant Reader, “Remarks on Mr. Laurie’s Letter Concerning Emigration from the Highlands of Scotland,” The Farmer’s Magazine 10, no. 38 (June 1809): 165.

[17] James J. Sack, From Jacobite to Conservative (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

[18] Jonathan Conlin, “Making an exhibition of himself: John Wilkes through Visual Sources,” Writing Visual Histories, ed. Florence Grant and Ludmilla Jordanova (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).

[19] Robert McColl Millar, “Homogenisation and Survival: The Languages of Scotland in the Eighteenth Century,” Sociolinguistic History of Scotland (Edinburgh University Press, 2020), 100–24.

[20] Marjo Kaartinen, “Luxury, Gender and the Urban Experience,” in Luxury and Gender in European Towns, 1700-1914 (Taylor & Francis, 2014), 1–18.

[21] Edmund Burt, “Letter III,” in Letters from a Gentleman in the North of Scotland to His Friend in London, ed. R. Jamieson (Ogle, Duncan, and Co., 1822), 45-6.

[22] Burt, “Letter V,” 92-3.

[23] Glenda Norquay, “Introduction,” in The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Women’s Writing, ed. Glenda Noquay (Edinburgh University Press, 2012), 1–10; and Ian Duncan, Scott’s Shadow: The Novel in Romantic Edinburgh (Princeton University Press, 2016), 79.

[24] “II. The Cottagers of Glenburnie, a Tale for the Farmer’s Ingle-Nook,” The Scots Magazine and Edinburgh Literary Miscellany (September 1808): 678–79.

[25] “Mrs. Elizabeth Hamilton,” The Literary Panorama 5, no. 26 (November 18, 1816): 1671. Similar texts were also published in non-literary publications. See “Character and Writings of Mrs. Elizabeth Hamilton,” The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle (December 17, 1816): 623–24.

[26] Elizabeth Isabella Spence, “Letters from the North Highlands,” Women’s Travel Writing in Scotland, vol. 4, ed. Kirsteen McCue and Pam Perkins (Routledge, 2017), 31–32.

[27] “Care system will suffer under UK immigration plan,” BBC, May 12, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0j78q84601o.

Cite this article as: Laura Golobish, “Piss, Poison, and other Paths between Scotland and England in Caricature since 1745,” Journal18, Issue 20 Clean (Fall 2025), https://www.journal18.org/8011.

Licence: CC BY-NCJournal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.