Elizabeth Eager

In a passage from her 1792 Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Mary Wollstonecraft raises a concern: women were spending too much time on their needlework. She argues that,

[female] reason will never acquire sufficient strength to enable it to regulate their conduct, whilst the making an appearance in the world is the first wish of the majority of mankind … From the same source flows an opinion that young girls ought to dedicate great part of their time to needle-work; yet, this employment contracts their faculties more than any other that could have been chosen for them.[1]

Rooted in the struggle to garner recognition for her own writing and its requisite intellectual labor, Wollstonecraft’s excoriation of women’s sewing as a practice that “contracts their faculties” and “weakens the mind” is frequently cited as evidence of the long-standing devaluation of women’s work in Western society and the perceived opposition between manual labor and mental acuity upon which such devaluation has been built.[2] However, Wollstonecraft’s critique also hinges on concerns about women’s productive use of time, shaped by an emergent labor theory of value rooted in the commercial and industrial revolutions of eighteenth-century Britain.

Situating her opposition of mental and manual labor in terms that are explicitly class conscious, Wollstonecraft further writes that,

when a woman in the lower rank of life makes her husband’s and children’s clothes, she does her duty, this is her part of the family business; but when women work only to dress better than they could otherwise afford, it is worse than sheer loss of time. To render the poor virtuous they must be employed, and women in the middle rank of life, did they not ape the fashions of the nobility, without catching their ease, might employ them, whilst they themselves managed their families, instructed their children, and exercised their own minds.[3]

Needlework thus represents a double loss in Wollstonecraft’s estimation—on the one hand, the “loss of time” for middle class women, their hours of leisure sunk into a menial task for which Wollstonecraft sees no conceptual return; on the other, the loss of wages for working-class women who could find no sewing work because middle-class women preoccupied themselves with self-made finery.

Wollstonecraft was not alone in this point of view. As part of the eighteenth-century literary society known as the Blue Stockings, Wollstonecraft joined fellow members Elizabeth Montagu and Hannah More in critiquing the frivolity of so-called “female accomplishments” like embroidery. Qualifying a similar argument regarding the opposition of the work of the needle and that of the intellect, the writer Mary Lamb notes in her 1815 letter to the editor of The British Lady’s Magazine, “I am afraid the root of the evil has not, as yet, been struck at. Work-women of every description were never in so much distress for want of employment.”[4] She goes on to ask her audience, “Is it too bold an attempt to persuade your readers that it would prove an incalculable addition to general happiness and the domestic comfort of both sexes if needle-work were never practiced but for a remuneration in money?”[5] As Nicole Pohl has noted, there was a notable, class-based distinction made by eighteenth-century authors as to the validity of a woman’s occupation with her needle. As she describes it, “the ‘work’ of needlework was … valued as economic necessity, a profession or as part of middling class ‘good housewifery’—but all as female ‘work.’ Any employment of these skills for personal embellishment and vanity was rejected as work and classified as ‘fancy’ sprung from the idleness of leisure and indicated a specific social standing.”[6] Pitting pleasure against politics, then, late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century reformers traced women’s impoverished place in society to an essential opposition between productive labor and the moral laxity of leisure activity.

Such critiques rely upon a labor theory of value rooted in the political economy of Adam Smith. As articulated in Smith’s Wealth of Nations, “The value of any commodity…is equal to the quantity of labor which it enables him to purchase or command. Labor, therefore, is the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities.”[7] As the fundamental unit of economic exchange, labor—while an admittedly difficult thing to precisely quantify—nevertheless provided a way of measuring both individual and collective contribution to the national economy. Situating Wollstonecraft’s discussion of authorial labor in the context of Smith’s economic theory, Jennie Batchelor has noted that “if Adam Smith was right to insist that ‘every individual [was] a burthen upon the society to which he belongs, who [did] not contribute his share of productive labour for the good of the whole,’ then women of leisure were little more than parasites.”[8] Following in this line of reasoning, Wollstonecraft sees women who worked with their needles because they had to as contributing productive labor to society, but believes those who had the leisure to do otherwise ought to direct their labors to intellectual self-improvement.

While recent scholarship on needlework, and indeed on craft more generally, has sought to upend the distinctions between manual and mental labor found in Wollstonecraft’s critique, there has been little attempt to grapple with the underlying presumptions about time and productivity upon which it was based and the way those presumptions—rooted in the eighteenth century’s emergent capitalist structures—continue to shape our own scholarly relationship to this material in the present. Although eighteenth-century sewing practices were diverse, spanning the utilitarian and the decorative, the amateur and the professional, the literature on needlework in the Anglophone context has overwhelmingly focused on the amateur practices of young women from upper and upper-middle class families and the ways in which such practices were employed in female education.[9] Literary scholars, in particular, have sought to demonstrate the reflexive relationship that developed between women’s pens and their needles and to trace the mutual constitution of material and textual literacy that evolved over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[10] However, this attempt to assert the connection between mental and manual labor in sewing has also been accompanied by an insistence on the productive value of that labor, emphasizing the elements of “work” in needlework and using it to highlight women’s value in the economy of the early modern household and thus in the economy at large.[11] Even though they arrive at different conclusions, contemporary scholars continue to valorize women’s sewing practices in precisely the terms previously employed to denigrate them.

Where Wollstonecraft and her contemporaries sought to disparage ornamental needlework by consigning it to the realm of leisure and frivolity, contemporary scholars are quick to point to the way in which the word “work” was, for Anglo-American women, largely synonymous with the practice of sewing. Indeed, the definition of work as “flowers or embroidery of the needle” is the fourth entry provided in Samuel Johnson’s 1755 Dictionary of the English Language (below “bungling attempt,” but above the more general category of “any fabrick or compages of art” [sic]).[12] In some cases the economic value of such work was self-evident, in so far as a woman’s ability to ornament a plain length of linen could be measured against the cost of the expensive imported textiles she sought to imitate and/or replace.[13] However, it is also common to speak of the social value of needlework in an upwardly mobile household, affirming that even if produced for neither remuneration nor to replace other financial outlays, the time and labor expended in its production nonetheless contributed to the consolidation of a family’s social and economic standing in their community.[14] Even as it has permitted a necessary restructuring of our understanding of women’s roles in the early modern economy, this recuperation of sewing as “work” leaves little room for an understanding of this practice as one pursued outside the realms of utility, productivity, or economic gain. Depending on conceptions of labor as a source of capital and time as a finite resource to be maximized, it is an approach that continues to value women’s work in terms set by a capitalist system designed to exploit it.

Departing from this model, the following essay examines the ways in which women used needlework to frame their own relationship to both labor and time apart from an expanding capitalist order contingent upon their optimization. Although I draw from a range of written, sewn, and drawn material from both Britain and British North America, the work of two women, in particular, grounds this inquiry. Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker (1735–1807) and Prudence Punderson [Rossiter] (1758–1784) were both well-educated, pious, and (at least initially) affluent members of North America’s merchant elite. Both are notable for their prolific needlework: Drinker’s recorded in an exceptional manuscript diary and Punderson’s in a remarkably large body of surviving embroidery. These were women who clearly enjoyed and took substantial pride in their use of the needle and whose material records reflect a conscious consideration of the role it played in their daily lives. Looking to materials and techniques as well as pictorial content, I examine these needleworkers’ fascination with temporal themes—from the fragmented moments of everyday life to the recursive structures of memory—to construct an alternative account between women’s labor and the “lost” time of leisure in the eighteenth century.

Of course, to validate the significance of needlework as a practice of pleasure rather than necessity risks eliding the ways in which such leisure hours were made possible by others’ labor. As Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has so succinctly described the labor dynamics of early American pastoral scenes, “For daughters of the gentry, the ability to embroider rural work was a mark of their having escaped it.”[15] In its formulation in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Britain, the picture of merry rustics that populated embroidered pastorals obscured policies of enclosure and privatization that increasingly drove the rural poor (particularly women) into exploitative systems of outwork weaving and spinning that guaranteed the availability of precisely those textiles necessary for the production of luxury embroidered objects (Fig. 1).[16] In Britain’s North American colonies, this dynamic was exacerbated by the pervasive presence of slavery and the extent to which forced labor underwrote the entire colonial economy.[17] My intent here is not to ignore the entrenched systems of privilege that granted some women the benefit of leisure hours while trapping others in generations of servitude or slavery. Nor is it to deny the myriad ways in which needlework was, in fact, work. It is rather to acknowledge that a capitalist framework enfolds all needlework, whether necessary or not, and to ask whether there is space outside of this framework for interpretation.

Marking Time

First-hand accounts attest to the persistent pace of sewing production among middle- and upper-class women of the eighteenth century. For example, the diaries of the Pennsylvania Quaker Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker reveal what must have been a near constant state of production in the years prior to her marriage.[18] Drinker was born in Philadelphia in 1735 to Sarah [Jarvis] and William Sandwith, merchant and shipowner. She was educated at the Quaker school run by abolitionist Anthony Benezet and married the merchant and fellow Quaker Henry Drinker in 1760. Referring repeatedly to the management of household servants (at times at least five in number), Drinker’s diaries suggest a degree of wealth that would have rendered her needlework more pastime than necessity, yet the production of watch-strings, stockings, pincushions, and petticoats recorded in her diaries also have to be understood in the context of Quaker religious principles, which prioritized qualities of sobriety, utility, and plainness.[19] Colored by religious conviction, Drinker’s needlework practices resist categorization as either the frivolous product of female leisure or the unremunerated contributions to a household economy. They are, rather, a recurrent accompaniment to a life spent in close society with friends and family.

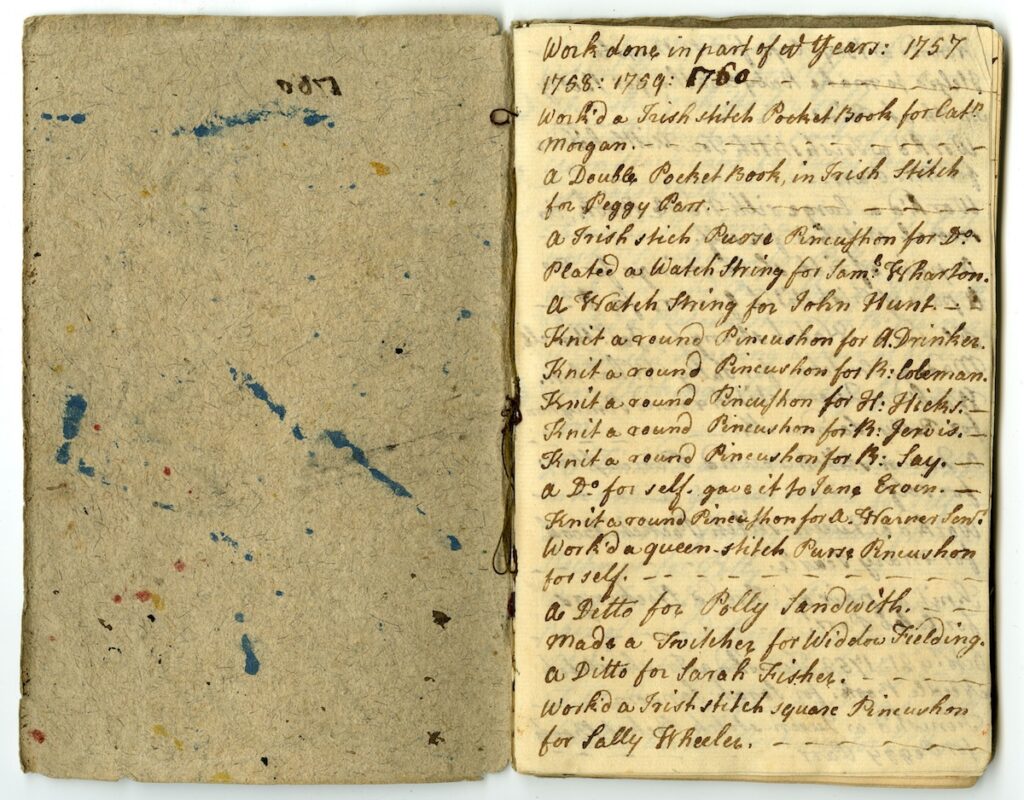

As preamble to the first volume of her diary, Drinker has listed the close to one hundred distinct items she produced between 1757 and 1760 by plaiting, knitting, plain sewing, and embroidery (Fig. 2). Carefully inscribed in a precise hand, the first two pages of the list appear to be retrospective, recounting objects Drinker had produced in the preceding year. Beginning at the bottom of the second page, however, an entry recording the completion of an “Irish-stitch Needle Book” has been dated October 21, 1758, a date roughly coincident with the October 8th start date of the subsequent diary. The list is thereafter punctuated by dates at intervals of a week to a month, charting the passage of Drinker’s life from girlhood to married woman in a stream of textile production. Marriage appears to have changed the terms of Drinker’s relationship to her sewing, with the inventory of projects ending in 1760, the year she wed Drinker. References to her sewing in the diary itself are far fewer for the period following her wedding, drowned out (particularly in the first decade) by the trials and triumphs of her growing children and records of illness amongst family and friends. Yet scattered references—to a bodice fit for a friend, a silk cloak to be sewn for her daughter, even the quality of linen to be had amidst the depravations of the American Revolutionary War—testify to the ongoing presence of needlework in her life.

The format of the inventory that begins Drinker’s diary bears special scrutiny. In contrast to the eighteenth century’s emergent wage labor system, Drinker uses this list to account for her own work by the piece, connecting her accounting to longstanding traditions of women’s piecework for hire across social strata—work also taken up intermittently and often on a seasonal basis, fit in between other forms of labor both remunerative and familial.[20] With its careful cataloging of distinctions in material, technique, and form, Drinker’s record-keeping supplies technical justifications for the variability in her speed, while also drawing attention to the ways in which the myriad interruptions of daily life might expand or contract the duration of her projects. Yet, it is also important to note that this was decidedly not work for hire. While many of the objects recorded in Drinker’s list are identified with the name of their recipient, and while her diary entries record the delivery of various pieces of work to her neighbors, nowhere does Drinker record a price paid. Rather these offerings and deliveries are embedded in a range of attendant activities that surrounded practices of needlework—the time spent fitting gowns, setting up quilting frames, drawing patterns for the use of friends—time typically spent in conversation or company with others, wrapped into conventions of sociability in daily life.[21] Presenting sewing as a shared activity, not only in the forms of gifts exchanged and received, but as part of a broader practice of collective authorship, Drinker’s diaries reveal the ways in which sewing was not a supplement to social relationships but rather an integument in their construction.

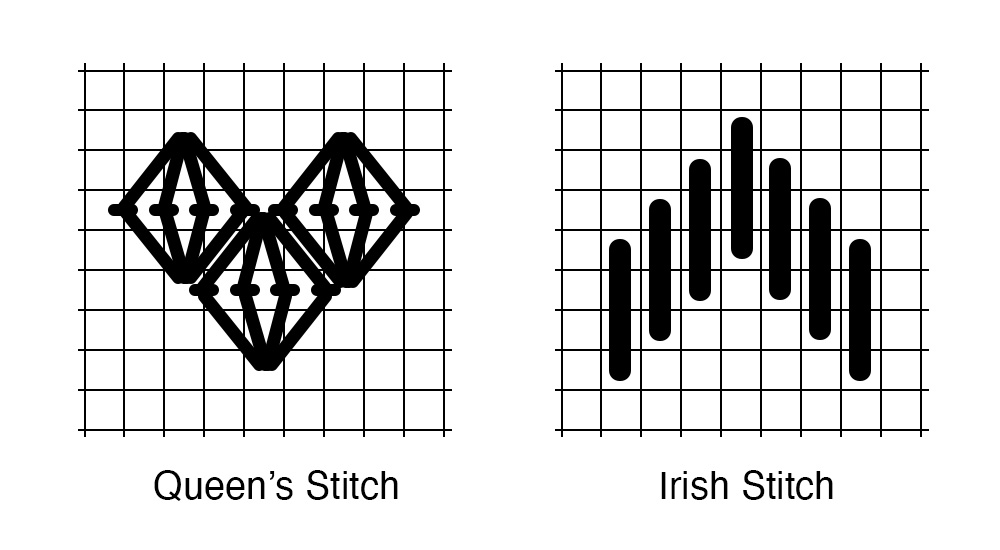

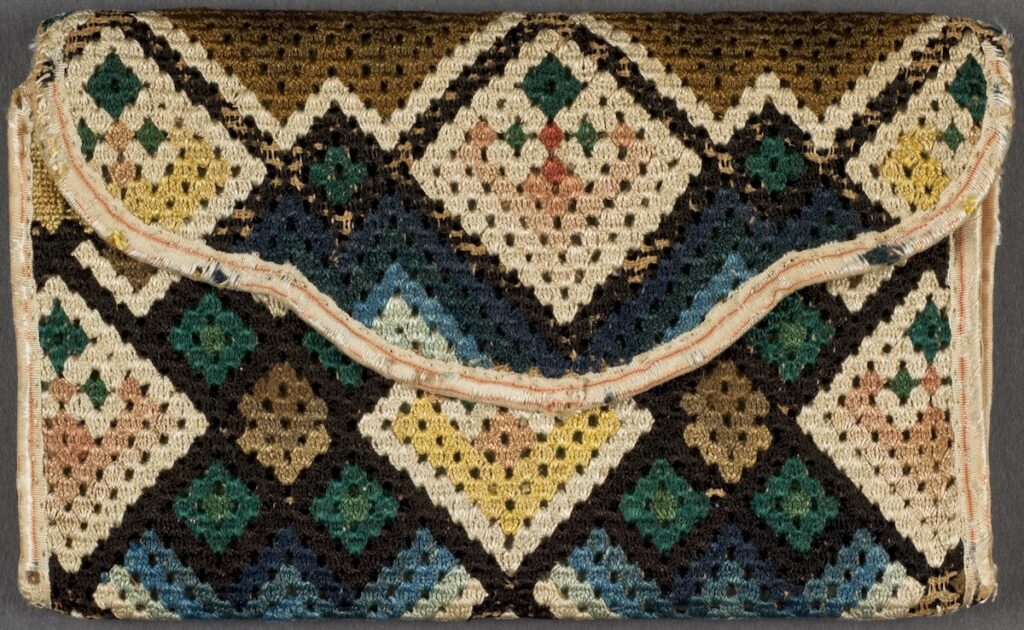

Recording the days that have passed between the successful completion of various items rather than the hours spent in their construction, Drinker’s list also implicitly acknowledges the ways in which these social relationships would have generated perpetual interruptions—visitations and family relocations, marriages and births, sicknesses and death—that would have rendered her work intermittent by default. However, the social structure of time—interrupted and intermittent—is also recorded in the shape of her work. Working most frequently in Irish stitch and queen’s stitch, Drinker seems to have relied on techniques that could be easily started and stopped and that automatically maintained a record of her progress in the physical form of her (countable) stitches. Both Irish and queen’s stitch are repetitive patterns, made up of long stitches that quickly cover a lot of ground as they move diagonally across the working surface (Fig. 3). Queen’s stitch in particular works in discrete units that can be easily organized into broad color fields or figural patterns, as seen in this eighteenth-century pocketbook by an unknown maker (Fig. 4). Composed of four or more individual stitches set in the shape of a diamond, the geometry of each queen’s stitch provides a guide to the placement of the next, making it relatively easy to leave off work and return at a later date.

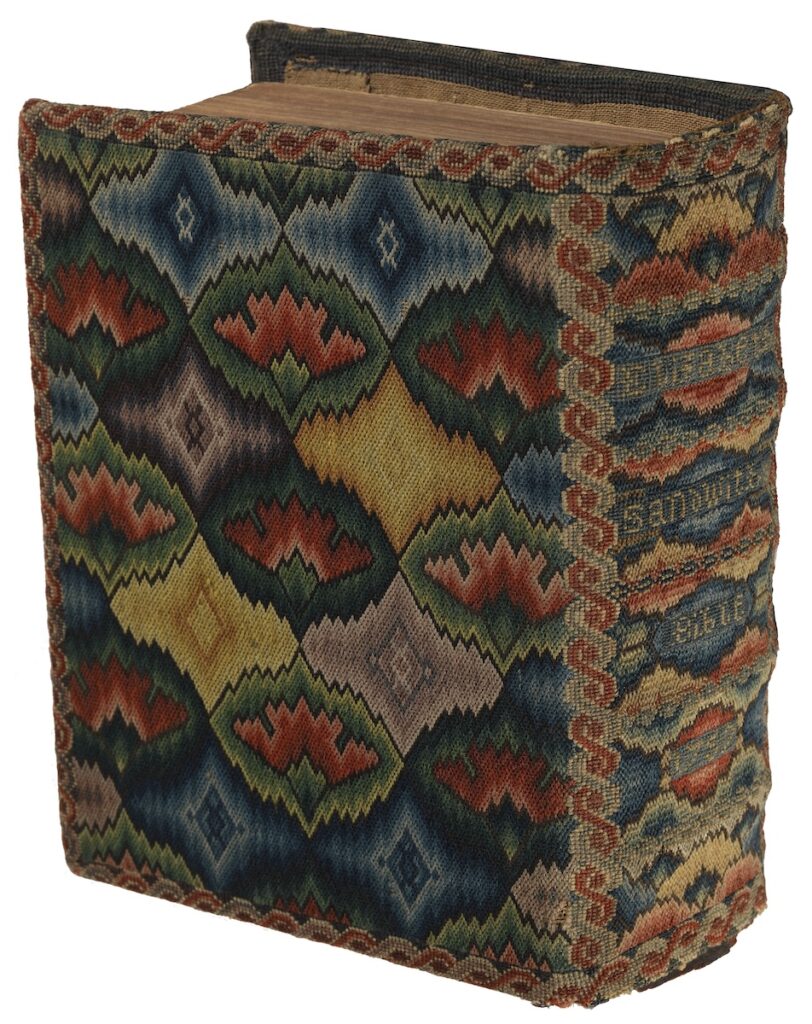

The Irish stitch that covers all three exterior surfaces of Drinker’s still extant prayer book would have lent itself to similarly episodic construction (Fig. 5). The entire composition is bilaterally symmetrical, but also composed of individual units symmetrical across a vertical (and sometimes also horizontal) axis. The gradations of color that give the surface its flame-like effect are executed in narrow bands that follow each motif’s jagged black border. Compare this construction to, say, a line worked in chain stitch (where the previous stitch cannot be completed without beginning a new one) or to satin stitch (which spreads quickly across an embroidery ground but implies no specific direction for the next stitch to be taken). In contrast, a design in Irish stitch is both self-contained and self-propagating, with each subsequent step encoded in the previous one—again, allowing Drinker the flexibility to easily pick up the work in spare moments of leisure and to put it down again as her attention was drawn to other matters.

Of course, Drinker was not alone in her experience of life’s constant interruptions. Such a condition is not only captured but romanticized in an engraving by James Gillray after a drawing by Lavinia, Countess Spencer in 1787 (Fig. 6). This scene, titled The Happy Mother,depicts a gloriously disheveled woman in déshabille turning from her tambour frame to regard one of her progeny, perched on tiptoes and on the verge of releasing a small bird into flight. With her tool still in hand, this so-called “happy mother” stops but does not abandon her work to oversee the anticipated release. Demonstrating her elegance and accomplishment while also signaling that her devotion is appropriately centered on the promise of a future generation, Spencer’s scene embodies the complex conditions for maternal happiness espoused by contemporaries like Priscilla Wakefield. Wakefield argued in Reflections on the Present Condition of the Female Sex (1798)that the pursuit of needlework was unsuitable to the situation of an “honourable and responsible” parent, yet her own diaries from the period 1798–99 indicate that it was a persistent, if occasional, part of her daily life.[22] In two years of near daily entries, there are eight that explicitly mention needlework and others that more generally address the various “employments” that occupied her in addition to her writing. Both Spencer and Wakefield seem to suggest that the virtuous mother is one who possesses expert knowledge of all female accomplishments, but who also dismisses these accomplishments as incompatible with maternal devotion.

As much as they attempt to articulate an idealized state of female virtue, Spencer’s scene and Wakefield’s words also capture a real-world dynamic familiar to anyone who has ever cared for a child while also trying to do literally anything else. Time in the context of child-rearing is fractured, divided into repetitive cycles of attention and distraction. As Wakefield herself notes at one point, “My time at present is much broken…I do not attempt anything but needlework of [which] I have much to do.”[23] Whereas queen of the Bluestockings Elizabeth Montagu spoke of knitting needles and other needlework equipment as instruments for killing or destroying time, Wakefield’s comments suggest time itself is already destroyed by the demands of sociability and communal care that fall upon a woman’s shoulders.[24] Rather than a means to destroy time, then, we might consider the ways in which needlework served to suture together the fractured moments of women’s experience. Within a framing bound to notions of “work,” we might characterize Sandwith’s catalog and Wakefield’s account of her sewing as opportunities for optimization—time not lost but recaptured from otherwise unusable intervals. However, I think it is also possible to see in these sources a recognition of needlework as a material throughline that stitched together myriad disparate moments into the larger fabric of a life—a fabric, as we will see in the next section, often marked by the stark disruptions of both birth and death.

Recursive Time

Kneeling before a stone monument, a young woman proffers a floral garland in an act of devotion familiar from innumerable embroidered pictures worked across both Europe and the United States in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (Fig. 7). The woman’s clothes, the urn before which she kneels, the weeping willow that shades the scene—these are all conventionalized attributes of the neoclassical mourning picture, a memorial worked in thread over days, weeks, or even years following the death of both close relations and esteemed public figures (Fig. 8).[25] Unusual in this example, however, is the fact that this scene was not mounted in a gilt frame and hung on the wall of the family home as either mnemonic trigger or testimony to female accomplishment. Rather, it was miniaturized, shrunk to only two inches in diameter to be sandwiched between the inner and outer case of a long-since separated pocket watch. While embroidered watchpapers are not uncommon from this period, the specific iconography of mourning invoked in this example contrasts poignantly with the structures of time-keeping enacted by the pocketwatch for which it was produced.

Initially a sign of elite status—as evidenced in the profusion of late seventeenth-century printed portraits that feature gentlemen prominently fingering their portable timepieces—the pocket watch emerged over the course of the eighteenth century as a potent sign of individualism and consumerism, a harbinger of nascent capitalism frequently tied to the performance of masculinity.[26] Recent scholarship has sought to nuance the perception of the pocket watch (and the mechanical clock more generally) as exclusively associated with temporal uniformity and discipline (the forerunner to nineteenth-century “factory time”) by highlighting the manifold temporalities that co-existed amidst industrialization’s transformation of eighteenth-century society.[27] Yet there is little doubt that eighteenth-century essayists, aphorists, and visual artists made explicit linkage between the clock’s careful regulation of seconds, minutes, and hours and a capitalistic maximization of time as a finite resource. To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin, the eighteenth century saw time turn into money.[28]

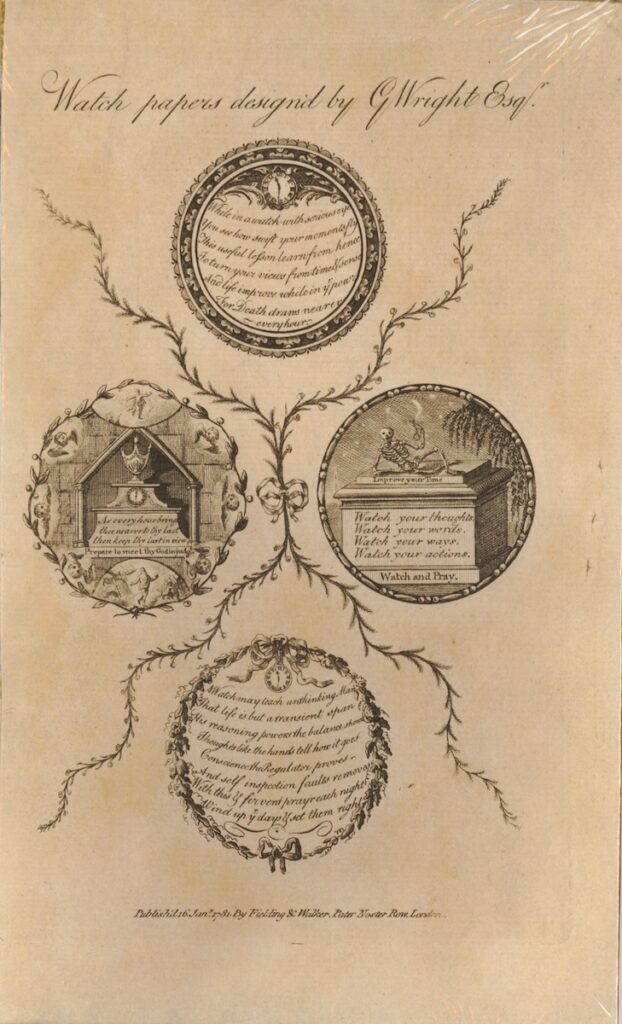

Such associations were frequently administered in moralistic tones, as in this set of printed watchpapers, designed (like the embroidered example above) to be cut out and inserted into the space between a pocket watch’s inner and outer cases (Fig. 9).[29] In one specimen, the reclining figure of an animated skeleton rests on a stone sepulcher engraved with the admonition to “Improve your time,” while dangling his own portable time piece from two bony fingers. Below, wrapped in a beribboned floral garland, a short piece of verse articulates a similar alignment of clock time and lifetime:

A watch may teach unthinking man

That life is but a transient span

His reasoning powers the balance showed

Thoughts like the hands tell how it goes

Conscience the Regulator proves –

And self inspection faults removes

With this & fervent prayr each night

Wind up yr days & set them right.

In these examples and others like them, the pocket watch serves as a representation of l’homme machine, a reminder of both the conceptualization of the body as a clockwork mechanism and of the body’s limited time on earth.[30]

As a memorial scene, the embroidered watch paper conforms to this broader phenomenon in which the pocket watch was understood to function as a memento mori, but its presence also introduces a small hiccup in the regular meter of mechanical time keeping. Speaking not to the subject contemplating his own death, but to the mourner seeking solace in remembrance, the memorial scene engages an affective register in which time is not necessarily experienced as regular, linear, or progressive. Those who have experienced personal loss know that grief impacts temporal experience in unique ways, collapsing disparate moments in time and space. Memory maintains a relationship to time that is not progressive, but recursive and iterative. Grief returns again and again, not in the regular cycles with which the clock’s hands move around its face, but in waves whose periodicity varies with both the passage of time and the strength of memory.[31]

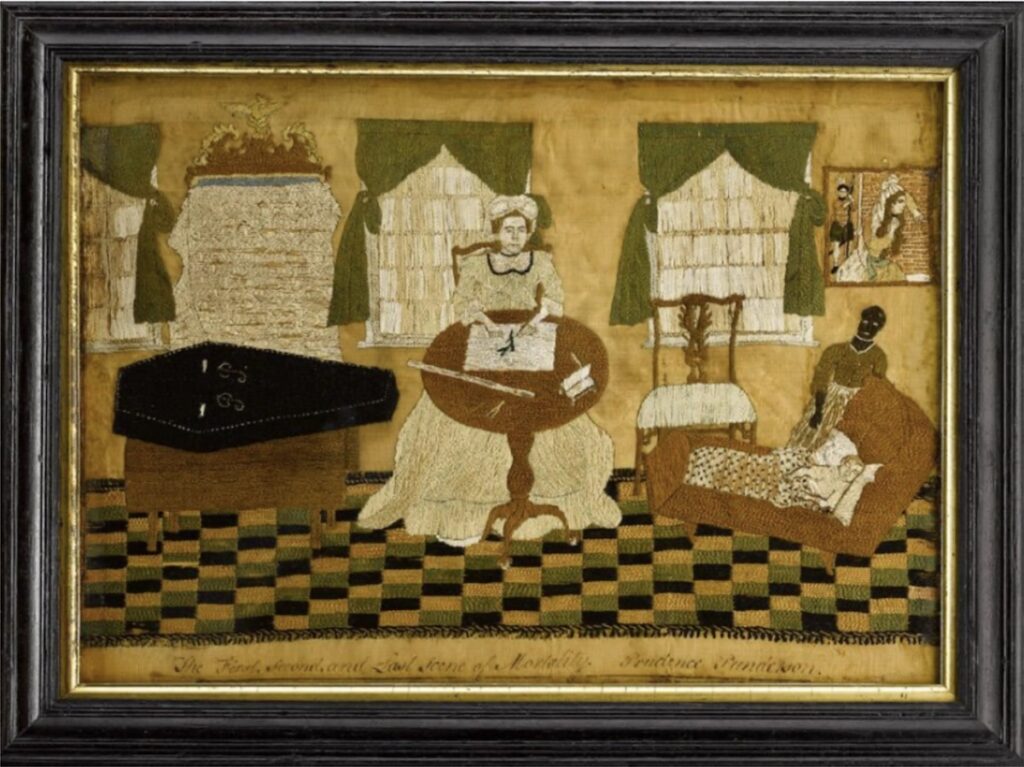

This recursive structure is given physical form in a 1783 work by the Connecticut embroiderer Prudence Punderson [Rossiter]. The daughter of a prosperous merchant and sometime schoolmaster, Punderson was a prolific needleworker, author of at least fifteen (known) works, including two embroidered hand-held firescreens and a series of twelve embroidered images of the Apostles. Her father’s store supplied the materials for her prodigious production, and its income (although interrupted by a period of exile during the American Revolution) allowed her the leisure to produce.[32] Her last known work, titled The First, Second, and Last Scenes of Mortality, depicts a household in mourning, marked by shrouded windows, a cloth-draped mirror, and a stark black coffin marked with the initials P.P. resting atop the drop-leaf table at left (Fig. 10). The coffin’s initials and the room’s contents—connected by scholars to specific items owned by the Punderson family—suggest the figure seated at the center of the composition is Punderson herself: alive, well, and at work on the drawing laid out before her. At right, a young child rests in a cradle, rocked by a Black attendant, speculatively identified as Jenny, an enslaved woman referenced in the 1805 will of Punderson’s father Ebenezer. [33]

In her analysis of this image, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich suggests that the scene is meant to be read sequentially, from right to left, directed by the inscribed text below and its ordinal arrangement of birth, life, and death.[34] We are to understand the image as representing Prudence in infancy, cared for by the family’s bondwoman; then proceeding to adulthood and engaged in a suitable female accomplishment; and culminating in her death, still ensconced in the family home. Reading the image left to right, however, places Punderson’s coffin in advance of the childhood scene, eerily foreshadowing her death only a month after the birth of her first child in 1784 and positioning the figure of the enslaved woman Jenny as both her oppositional term and her maternal replacement. It is also worth noting that Punderson shared initials with her mother, Prudence Greer Punderson, such that the delicately embroidered text on the coffin’s lid would have prompted contemplation of the author’s own mortality as well as her mother’s. In this reading, Punderson is situated between her mother and the woman who would have cared for her in her mother’s absence, the two maternal figures linked as spectral presences by the dark thread used to render both the coffin and Jenny’s skin. Rather than a sequential unfolding of life in an orderly progression, then, Punderson’s embroidery presents multiple, overlapping chronologies. Interweaving the time frames of maternal life and death, the embroidery highlights not only the fragility of life in general but also the specific uncertainties of female mortality in the eighteenth century.

As Susan Stabile has argued, this way of keeping time was particularly associated with women in this period. “By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, consolation manuals and elegies typically gender grief as the feminine other, to be overcome by the rational, male mourner” whose grief is delimited by an appropriate period, exhausted by the eventual passage of time.[35] In contrast, the perpetual return orchestrated through female grief is understood to be at odds with the linear, forward progression of horological time—recursive, redundant, excessive. It is, perhaps, no accident that these are the same terms in which women’s needlework is described by period critics. When Mary Lamb encourages the well-off woman to lay her needle-book aside and contribute “her part to the slender gains of the corset-maker, the milliner, the dress-maker, the plain worker, the embroidress,” she casts needlework as an occupation of excess, easily duplicated by any number of professional purveyors on the commercial market. Likewise, in arguing that “it is a very erroneous misapplication of time, for a woman who fills the honourable and responsible character of a parent, to waste her days in the frivolous employment of needle-work” and that “it would be a more profitable disposal of time and money, to hire a substitute for the management of these less important concerns,” Priscilla Wakefield proposes that needlework’s excesses upset a more rational ordering of both time and money.[36] In its embrace of recursive time, however, Punderson’s embroidery posits a different purpose for the work of hand and needle—navigating, negotiating, and processing the unique conditions of temporal experience that governed women’s lives in the eighteenth century.

Women’s Time

While Punderson’s self-portrait amidst this scene of life and death challenges the notion of a rational, linear ordering of time, the figure of Jenny, the enslaved woman who serves as Punderson’s compositional and maternal counterpoint, introduces a different kind of disruption. Jenny’s presence, particularly as portrayed in her role as familial caretaker, belies the fiction of a perfectly rational economy, premised exclusively on the fair exchange of wage-labor. For critics like Lamb or Wakefield, the unremunerated labor of the British housewife may have been tantamount to slavery, but for the vast majority of North America’s Black population, slavery was a lived reality, and one that diverged in its own, specific ways, from the temporal order(s) experienced by their enslavers, male and female alike. The context of mourning, introduced by Punderson’s picture, is a particularly salient example. As Christina Michelon has recently argued in her discussion of a nineteenth-century memorial portrait, the visual culture of white grief has been constructed in such a way that it forecloses the possibility of Black grief, particularly in the context of slavery. Even as white violence was so often the cause of death for people of color, their labor was consistently appropriated to mourn white masters.[37] Such is the case in Punderson’s picture. Standing witness to the cycles of birth, life, and death that structure the image, Jenny performs the role of both surrogate mother and mourner without reference to her own biological or chosen family—not a figure in her own right, but an accessory to Punderson’s linkage of mortality and matrescence.

Yet there are also records of the ways in which needlework—at least in certain cases—offered enslaved women a way of claiming time from within those structures imposed by their enslavers. As Jacqueline Jones has suggested, “the burdens shouldered by slave women actually represented in extreme form the dual nature of all women’s labor within a patriarchal, capitalist society: the production of goods and services and the reproduction and care of members of a future work force.”[38] While enslaved women sewed (and spun and wove) for their enslavers’ households, with such skills advertised by slave traders as a way to increase a person’s value at auction, such activities also enabled women greater mobility, particularly in urban areas, and thus offered limited time away from their enslavers’ control.[39] In some cases, these women were also able to contract for piecework on the open market as a means to earn independent income. In at least two recorded examples, women used such income to fund their self-emancipation.[40] The time used to produce this work, or to clothe oneself or one’s children, was time seized from their enslavers. Born on a plantation in Lexington, Georgia, in the mid-nineteenth century, Martha Colquitt relayed to the Federal Writer’s Project reporter who interviewed her in the 1930s that her mother and grandmother religiously carved out time at the end of the day to work on textiles for their family.[41] Although she indicated that her mother and grandmother understood the labor expended in spinning, knitting, and sewing as work, she also emphasized that it was work undertaken of their own volition. The hours they spent with needles in hand cannot reasonably be classified as leisure, but nor do they neatly fit into the category of “productive labor.” Instead, they can be understood as a form of resistance within a system designed to extract as much productivity as possible from every enslaved man, woman, and child.

The way in which slavery impacted all social relationships—whether between mother and child, husband and wife, or enslaver and enslaved—means that the experiences captured in the embroideries of wealthy, white women cannot simply be extrapolated to the Black women who may have populated both their pictures and their parlors.[42] Given such differences, I am resistant to assertions of some essentializing definition of “women’s time,” such as that expressed by Julia Kristeva in her characterization of female temporality as inherently and essentially cyclical. In Kristeva’s account, the cycles that govern menses and gestation establish “the eternal recurrence of a biological rhythm which conforms to that of nature … as a consequence, there is the massive presence of monumental temporality, without cleavage or escape, which has so little to do with linear time (which passes) that the very word ‘temporality’ hardly fits.”[43] In a similar vein, E.P. Thompson argues in his foundational study “Time, Work-Discipline, and Capitalism” that “despite schooltimes and television times, the rhythms of women’s work in the home are not wholly attuned to the measurement of the clock. The mother of young children has an imperfect sense of time and attends to other human tides. She has not yet altogether moved out of the conventions of ‘pre-industrial’ society.”[44] While such characterizations serve to elide the very real differences that distinguish the lived experiences of women across the social spectrum, I do think it is worth drawing attention to the ways in which women themselves have marked a relationship to time that operates outside the bounds of a capitalist structure. Certainly, the passage of time recorded in Elizabeth Sandwith’s diary or Prudence Punderson’s embroidered picture cannot be measured in incremental units of wage labor or easily parlayed into capitalism’s systems of commodity exchange. Although qualifiably different in both kind and context, the moments captured by enslaved women as they sewed in secret similarly occupy a space outside the normative systems of a capitalist economy. The intermittent and recursive structures teased out in this analysis are precisely why women’s labor has proved so difficult to capture within traditional economic measures.

The solution is not, however, to simply reclassify all of women’s activities with needle and thread as “work.” As defined within the emergent capitalist structures of eighteenth-century society, the category of work presupposes an opposition between productive and unproductive labor, between hours that generate value and those that do not.[45] By highlighting the role of women’s needlework in the generation of both physical and social capital, historians have sought to capture the significance of women’s labor within capitalism’s binary paradigm. However, the examples explored in this essay suggest that for women in the eighteenth century, the manipulation of needle and thread was not to be so easily categorized. As a physical activity, sewing was interstitial, capturing rather than creating lost time amidst the fractured moments of daily life. In turning so often on moments of transition, sewing’s subject matter served as a means to process temporal uncertainty and to register the unfolding of time in ways seemingly arbitrary and unforeseen. Sewing was a form of sociability and a form of activity that proved both pleasurable and productive. To reduce such activity to the category of work is to threaten its fundamental complexity and multiplicity. In attending to the interstices and the recursions revealed through needle and thread, however, we are witness to a fuller accounting of women’s labor, registered in found moments and fractured experiences, stitched together to fabricate a life.

Elizabeth Eager is Assistant Professor of Art History at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, TX

[1] Mary Wollstonecraft, Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects [1792] (London: for J. Johnson, 1796), 164.

[2] See, for example, Jennie Batchelor, Women’s Work: Labour, Gender, Authorship, 1750-1830 (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2010), 109-13; Roszika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (New York: Routledge, 1984), 1-11.

[3] Wollstonecraft, Vindication of the Rights of Woman,164.

[4] Mary Lamb, “On Needlework,” The Lady’s Magazine or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, Appropriated Solely to Their Use and Amusement (April 1815): 205.

[5] Lamb, “On Needlework,” 205.

[6] Nicole Pohl, “‘To Embroider What is Wanting’: Making, Consuming and Mending Textiles in the Lives of the Bluestockings,” in Material Literacy in Eighteenth-Century Britain: A Nation of Makers, ed. Serena Dyer and Chloe Wigston Smith (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2022), 69.

[7] Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776), 1:35.

[8] Batchelor, Women’s Work,110.

[9] It should be noted that this is beginning to change; see, for example, Serena Dyer, Labour of the Stitch: The Making and Remaking of Fashionable Georgian Dress (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2024); Arianne Fennetaux & Barbara Burman, The Pocket: A Hidden History of Women’s Lives, 1660–1900 (London & New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

[10] See, for example, Maureen Daly Goggin, “Visual Rhetoric in Pens of Steel and Inks of Silk: Challenging the Great Visual/Verbal Divide,” in Defining Visual Rhetorics, ed. Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004), 87-110; Heather Pritash, “The Needle as the Pen: Intentionality, Needlework, and the Production of Alternate Discourses of Power,” in Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles, 1750–1950, ed. Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (Farnham, UK; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 13–30; Susan Frye, Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010); and Dyer and Wigston Smith, “Introduction” to Material Literacy in Eighteenth-Century Britain, 1–15.

[11] See for example, Frye, Pens and Needles, 126–8; Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Vintage Books, 2001),148; Elizabeth White Nelson, Market Sentiments: Middle-Class Market Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2004), 132.

[12] “work, n.s.” A Dictionary of the English Language, by Samuel Johnson (London: W. Strahan, 1773). https://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/1773/work_ns (all weblinks accessed 2/10/2024)

[13] Frye, Pens and Needles, 128.

[14] See, for example Jennifer Van Horn, “Samplers and the Middling Sort,” Winterthur Portfolio 40, no. 4 (Winter 2005): 226–7.

[15] Ulrich, Age of Homespun,154.

[16] Ulrich, Age of Homespun, 152, referencing Raymond Williams, “Pastoral and Counter-Pastoral,” Critical Quarterly 10, no. 3 (September 1968): 277–90.

[17] Jill Casid, Sowing Empire: Landscape and Colonization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005); Zara Anishanslin, Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 47–8.

[18] Original diaries, vol. 1, Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker diaries (Collection 1760), The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. See also the edited and abridged version, Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker, The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker: The Life Cycle of an Eighteenth-Century Woman, ed. Elaine Forman Crane (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 3–22; as well as the work of Drinker’s contemporary Hannah Callender Sansom, The Diary of Hannah Callender Sansom: Sense and Sensibility in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. Karin A. Wulf and Susan E. Klepp (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010).

[19] Laura Earls, “‘by her needle maintain herself with reputation:’ Philadelphia Quaker Women and the Materiality of Piety, 1758-1760,” Madison Historical Review (Spring 2021), https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/mhr/vol18/iss1/4; J. William Frost, “From Plainness to Simplicity: Changing Quaker Ideals for Material Culture,” in Quaker Aesthetics: Reflections on a Quaker Ethic in American Design and Consumption, ed. Emma Jones Lapsansky and Anne A. Verplanck (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 18-29.

[20] Deborah Valenze, The First Industrial Woman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 46.

[21] Drinker, Diary,3-22.

[22] Priscilla Wakefield, Reflections upon the Present Condition of the Female Sex, with Suggestions for its Improvement (London: J. Johnson, 1798), 44-5; Wakefield, “Transcript of Priscilla Wakefield’s Journal1798-1799,” ed. Ruth Graham, https://pw1751journal.wordpress.com/about/.

[23] Wakefield, “Journal.”

[24] Elizabeth Montagu, quoted in Pohl, “To Embroider What is Wanting,” 68.

[25] Laverne Muto, “A Feminist Art—The American Memorial Picture,” Art Journal 35, no.4 (Summer 1976): 352–8; Maureen Daly Goggin, “Stitching (in) Death: Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century American and English Mourning Samplers,” Women and the Material Culture of Death, ed. Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (Farnham, UK and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013), 63–90.

[26] David Landes, Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983), 92; Amanda Vickery, Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2009), 264; Marcus Tomalin, “The Intriguing Complications of Pocket Watches in the Literature of the Long Eighteenth Century,” The Review of English Studies 66, no. 274 (April 2015): 300–303.

[27] See, for example, Paul Glennie and Nigel Thrift, Shaping the Day: A History of Timekeeping in England and Wales 1300-1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[28] Benjamin Franklin, “Advice to a Young Tradesman,” printed in George Fisher, The American Instructor: or Young Man’s Best Companion (Philadelphia: B. Franklin and D. Hall, 1748), 375–7.

[29] David Landes traces this tradition to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Landes, Revolution in Time,95.

[30] The phrase “l’homme machine” specifically references the work of the mid-eighteenth-century philosophe Julien Offray de La Mettrie, who published a 1747 text under this title. However, it may also be understood to encompass a broader conceptualization of the body’s physiological processes and sensory inputs as mechanical in nature that prevailed in European philosophy from the mid-sixteenth through the early nineteenth centuries. Jessica Riskin, The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument over What Makes Living Things Tick (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2016), 3-8.

[31] Sociologist Neil Small describes grief as process that “fractures the sequential experience of time,” quoted in Lucy Clarke, “The domestic geographies of grief: Bereavement, Time, and Home Spaces in Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping and Home,” in Marilynne Robinson, ed. Jennifer Daly et al. (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2022), 143-64.

[32] Ulrich, Age of Homespun, 231-2.

[33] Ulrich, Age of Homespun, 229; see also Susan P. Schoelwer, Connecticut Needlework: Women, Art, and Family, 1740–1840 (Hartford, CT: Connecticut Historical Society, 2010), 86-89.

[34] Ulrich, Age of Homespun, 237-8.

[35] Susan Stabile, Memory’s Daughters: The Material Culture of Remembrance in Eighteenth-Century America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), 181.

[36] Wakefield, Reflections,44-5.

[37] Christina Michelon, “The In/Visibility of Mourning: Seeing Labor, Loss, and Enslavement in an Antebellum Posthumous Portrait,” American Art 35, no. 2 (Summer 2021), 78-101. Michelon’s interpretation builds on that of Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 121.

[38] Jacqueline Jones, “‘My Mother was Much of a Woman’: Black Women, Work, and the Family Under Slavery,” Feminist Studies 8, no. 2 (Summer 1982), 236. See also Jennifer Morgan, Laboring Women: Gender and Reproduction in the Making of New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004);Alexandra J. Finley, An Intimate Economy: Enslaved Women, Work, and America’s Domestic Slave Trade (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[39] Karol K. Weaver, “Fashioning Freedom: Slave Seamstresses in the Atlantic World,” Journal of Women’s History 24, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 44; Finley, An Intimate Economy,3-7.

[40] Morgan, Laboring Women, 159.

[41] “At night ma always spinned and knit, and grandma, she sewed, makin’ clo’es for us chillum. Dey done it ‘cause dey wanted to. Dey wuz workin’ for deyselves den. Dey won’t made to work at night.” Federal Writers’ Project, Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, 17 vols. (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1941)4:239. As Catherine Stewart has discussed, these narratives are in fact highly mediated texts, written up in a codified “Negro dialect” developed by white folklorists from the Federal Writers’ Project that served to both homogenize and exoticize the speakers. While acknowledging its problematic nature, I have opted to include the text as published here in addition to the paraphrase above, since any subsequent alteration would seem to take us even further away from Colquitt’s original self-expression. Catherine Stewart, Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 78-88.

[42] Finley, An Intimate Economy, 5-7.

[43] Julia Kristeva, “Women’s Time,” trans. Alice Jardine and Harry Blake, Signs 7, no. 1 (Autumn 1981): 16.

[44] E.P. Thompson, “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism,” Past & Present (December 1967): 79.

[45] Tim Ingold, “Work, Time, and Industry,” in The Perception of the Environment (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), 323-326.

Cite this article as: Elizabeth Eager, “Labor, Leisure, and Lost Time in Eighteenth-Century Women’s Embroidery,” Journal18, Issue 18 Craft (Fall 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7588.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.