Andrea Morgan

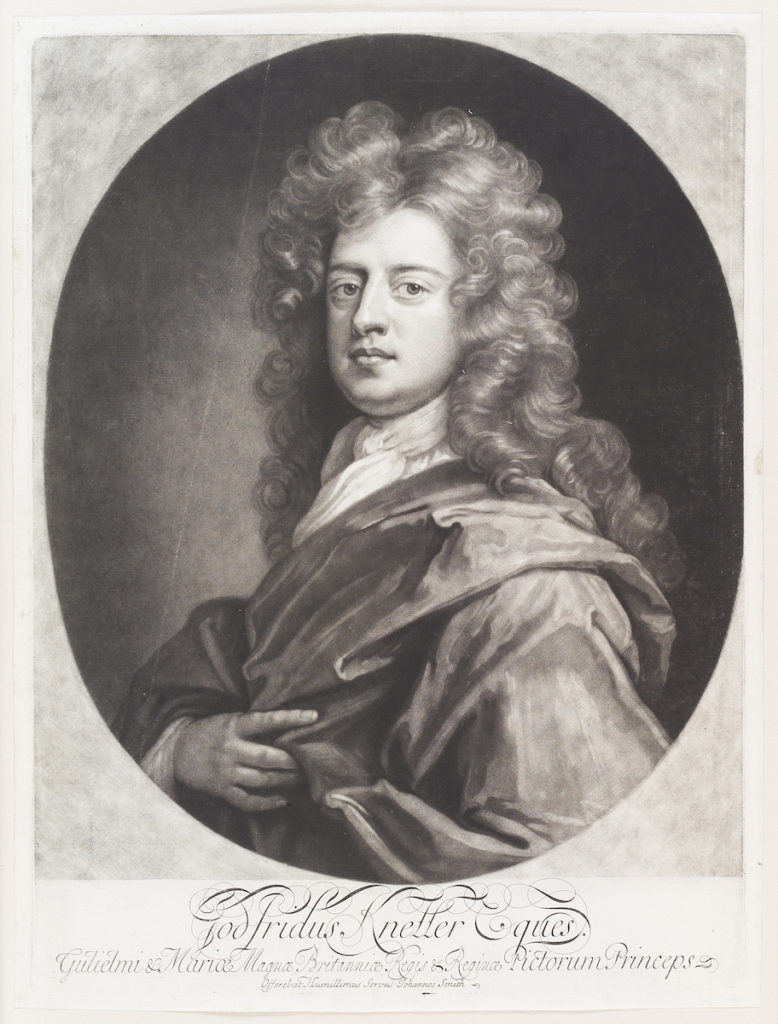

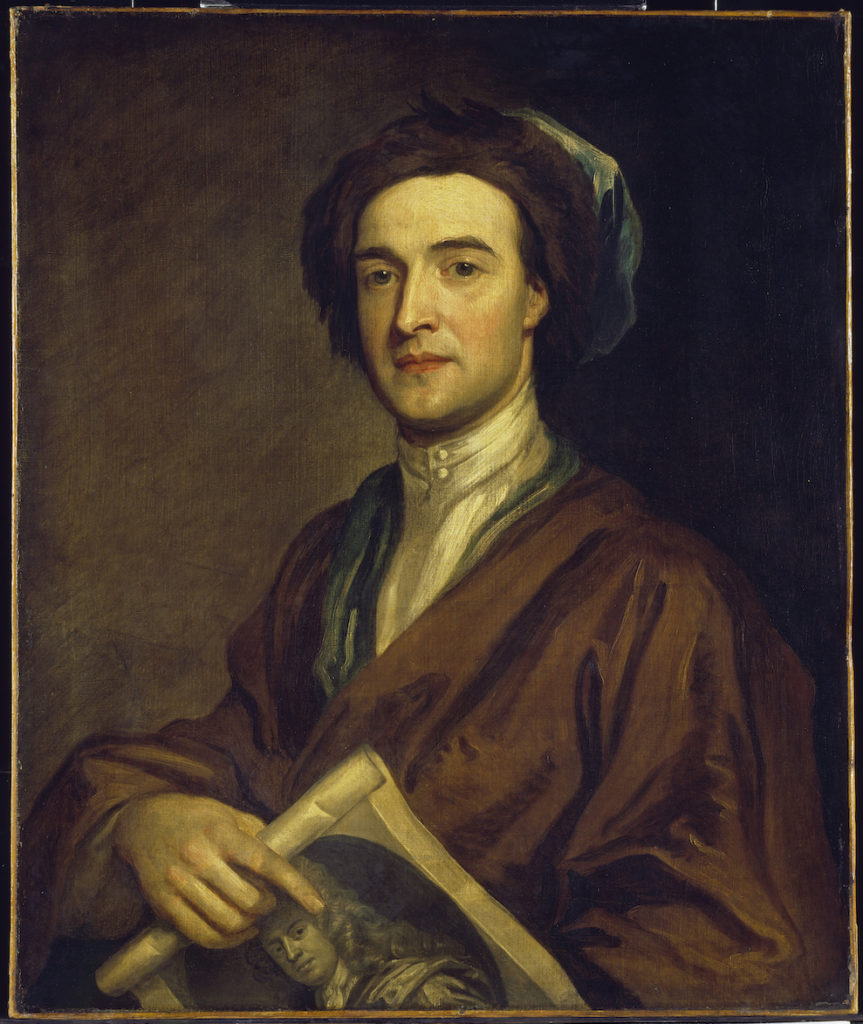

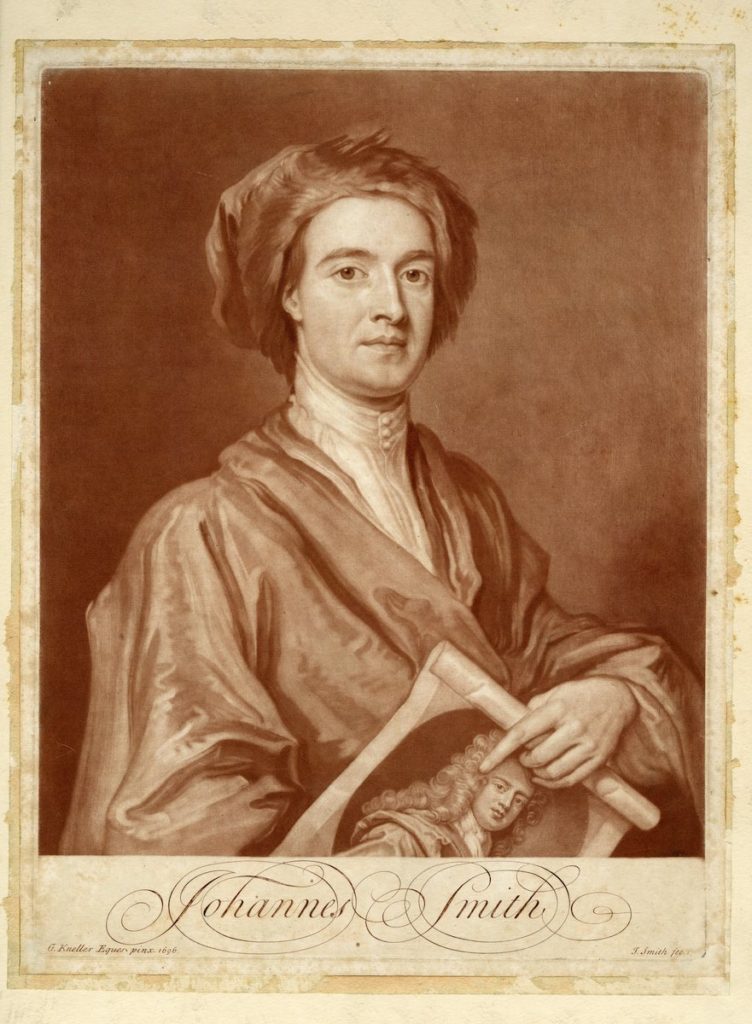

Between 1688 and 1716, John Smith (1652-1743) and Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) executed a collaborative series of four self/portraits. Smith was a mezzotint artist who produced over 100 copies after Kneller’s paintings, and this portrait series documents the decades-long partnership between the two artists that would prove valuable to both painter and printmaker. The first image is a Self-Portrait in oil by Kneller dating from 1688-1690 (Fig. 1). A standard portrait bust in oval format, Kneller painted his own likeness for the gentleman’s club to which he belonged, the Honourable Order of Little Bedlam.[1] In 1694, Smith copied in reverse a mezzotint of Kneller’s self-portrait, with a signature describing himself as Kneller’s “most humble servant” (Fig. 2). The third picture in the series is a portrait of Smith painted by Kneller in 1696 (Fig. 3). Kneller must have been keen to illustrate his partnership with Smith as he painted his friend holding an impression of the mezzotint copy that Smith had made after Kneller’s 1688-1690 self-portrait. Indeed, the 1696 painting was a gift dedicated to Smith from Kneller as result of their close business collaboration and friendship. Finally, in 1716, Smith engraved in mezzotint a copy of his own portrait that was first painted by Kneller in 1696 (Fig. 4). Just as Kneller dedicated the 1696 painting to Smith, Smith once again signed his 1716 print as Kneller’s “most obedient servant.”[2]

Kneller’s 1696 painting (Fig. 3) and Smith’s 1716 mezzotint (Fig. 4) stand out for the fact that they are simultaneously self-portraits and double portraits. However, Smith’s 1716 print is a copy, and in both images we see the two artists and their respective professions merged together, seemingly blurring authorship and identity. While the 1696 painting is a clear statement of comradery and collaboration, it arguably highlights, rather than diminishes, each man’s independent professional identity. This is because, instead of painting a conventional double portrait, Kneller reproduced in oil an engraved copy of his own likeness which Smith had printed two years earlier. The interplay of the two different media therefore offers a visual distinction between each man and his profession, resulting in a unique but cohesive double portrait.

More broadly, these images speak to the contexts in which they were made. In both pictures (Figs. 3 and 4), Smith’s index finger is pointing downward, directing the viewer’s attention to his own print of Kneller’s self-portrait. This visual suggestion, as well as the series as a whole, illustrates the artistic self-reflexivity on the part of both Smith and Kneller and was therefore another acknowledgement of each man’s métier. Such a statement was important during the early modern period as printmaking was still overcoming its association with manual craft, and since the genre of portraiture, though increasingly popular, was generally not highly regarded in the art theory of the period. These are problems which Smith and Kneller would have recognized, adding to the layers of meaning behind the 1696 painting and the 1716 print.

The collaborative model Smith and Kneller adopted was not an isolated example. Hannah Williams, in her 2015 study of the Académie Royale, discusses a contemporary case of a similar artistic exchange seen in the work of the French portraitist Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743) and the engraver Gérard Edelinck (1640-1707), both academicians.[3] In 1698, Edelinck engraved in reverse a copy of a self-portrait by Rigaud which was first painted in 1692; later, in 1698, Rigaud proceeded to paint a portrait of Edelinck.[4] Edelinck’s print and Rigaud’s 1698 painting were declarations of the friendship between the two artists as evidenced by the Latin inscriptions on the images.[5] Williams argues that this dialogue took place at a moment where Edelinck and Rigaud worked closely together and that “the two portraits they made of each other in 1698 were an embodiment of that artistic exchange. As Edelinck engraved the painter and Rigaud painted the engraver, the making of these objects gave substance to the reciprocal collaborations through which their friendship had formed.”[6] Just as Smith and Kneller had dedicated their 1694, 1696, and 1716 artworks to each other, in a similar demonstration of friendship and acknowledgement of artistic partnership Edelinck and Rigaud collaborated to enhance and document their own careers and relationship through the same lens of self/portraiture.

A notable difference between Edelinck and Rigaud’s relationship and that of Smith and Kneller is that Edelinck, although an engraver, was, as Williams explains, a senior member of the Académie and therefore Rigaud’s superior.[7] It was through their interaction in the studio, a less formal space which afforded opportunity for more intimate interaction, that their collaboration and friendship evolved, as Rigaud was keenly involved in the printmaking process with Edelinck and his other engravers.[8] The opposite holds true for Smith and Kneller, but their partnership was still advantageous for both artists. Kneller was indeed among the most celebrated painters in England during the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries and, as a portraitist, he was working in the most popular genre at court and in the eyes of the English public. Yet, the many printed copies of Kneller’s portraits which Smith produced advertised his work to a larger audience, both at home and abroad. At the same time, prints were modestly priced compared to paintings, providing a wider range of collectors the opportunity to own an example of Kneller’s body of work, further aiding to preserve his name for posterity. Kneller’s 1696 portrait of Smith can thus be viewed as evidence of his appreciation for his working relationship with his friend, John Smith, the printmaker.

For Smith, a collaboration with the likes of Sir Godfrey Kneller allowed him to make a name for himself and he soon established a favorable reputation with collectors in London and on the continent. Smith had become successful enough by the late eighteenth century that he did not need to advertise his work, as some engravers did, because serious collectors paid subscriptions to receive each print as the plates came out.[9] He likewise was a sharp businessman and came to publish his own prints. This allowed him to maintain his plates—something especially important for mezzotint as the plates wear quickly—ensuring the quality of the works printed and allowing him to charge premium prices.[10] That Smith was particularly concerned with the ownership and quality of his plates is made evident by a stipulation in his will that his plates be scraped after his death so they could not be reprinted.[11] This was ultimately not carried out, as some plates were reworked by the mezzotint artist Richard Earlom while others were acquired by the notable printseller John Boydell.[12] Boydell began to advertise impressions of Smith’s plates as early as 1767, and these helped preserve Smith’s reputation into the mid-to-late eighteenth century, despite being against his wishes.[13]

Studying these types of relationships can provide a glimpse into the mindset and ambitions of artists like Smith and Kneller. These partnerships and friendships—made visual through the self/portrait—were based on mutual respect and admiration but also on the desire to enrich (and, in Smith’s case, establish) their own careers and reputations. Smith’s example shows that artistic identity is not always fixed and that, despite the limitations of his chosen media as dictated by contemporary academic theory, he was not just a copyist. Printing himself in 1716 alongside the likes of Kneller gave Smith agency and may have been an attempt to raise not just his own status but that of his art form: his portrait prints were no longer mere reproductions but rather works of art in their own right.[14] As Antony Griffiths suggests, Smith may have waited until 1716 to execute this picture because it would have been “presumptuous” in 1696 when he was still establishing himself.[15] Griffiths speculates that two decades later, in 1716, Smith finally “felt himself to be a sufficiently great man to join his own portrait series.”[16]

This idea is corroborated by Smith’s later habit of undertaking the difficult task of compiling albums and collections of his own work, an enterprise Griffiths says is unparalleled by any other printmaker.[17] For Griffiths, Smith exhibited “remarkable self-consciousness,” and he must have become “fully aware of his own value and historical importance.”[18] It seems Smith’s contemporaries would have agreed. In his Catalogue of Engravers of 1796, Horace Walpole described Smith as “the best mezzotinter that has appeared.”[19] George Vertue, the English antiquarian and writer, similarly offered high words of praise in the obituary he had written upon Smith’s death, where he stated that Smith’s “fame was universally known to all ingenious persons of his time in England” and that “his work was of no less esteem abroad in foreign countries in France, Holland, Flanders, Germany & Italy.”[20] Vertue even argued that Smith “first brought [the mezzotint] to perfection” and that none since had been able to equal the quality of his execution.[21] It is clear, then, that by way of the self/portrait, his exchanges with Sir Godfrey Kneller, and his own talents and business savvy, Smith achieved a level of professional success that surpassed even his own expectations.

Andrea Morgan is a

PhD candidate at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario

Acknowledgements: Research for this paper was carried out during a Curatorial Practicum at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. With special thanks to Dr. Jacquelyn N. Coutré, Bader Curator and Researcher of European Art.

[1] Each member of the Little Bedlam club had an animal avatar and Kneller’s was a unicorn, a subtle depiction of which can be seen over the artist’s left shoulder. Smith excluded the unicorn from his 1694 mezzotint copy.

[2] Antony Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain (London: British Museum Press, 1998), 241.

[3]Hannah Williams, Académie Royale: A History in Portraits (New York: Routledge, 2015). For a discussion of a similar collaboration between Rigaud and Pierre Drevet, see 221-233.

[4] Hyacinthe Rigaud, Self-Portrait in a Red Cloak, oil on canvas, 1692, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe; Gérard Edelinck after Hyacinthe Rigaud, Self-Portrait in a Red Cloak, engraving, 1698, British Museum, London; Hyacinthe Rigaud, Gérard Edelinck, oil on canvas, 1698, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

[5] See Williams, Académie Royale, 223-224.

[6] Williams, Académie Royale, 224-225.

[7] Williams notes that oil painting would have outranked engraving as a medium but that Edelinck held the higher rank of conseiller and Rigaud that of an agréé. See Williams, Académie Royale, 226-227.

[8] Williams, Académie Royale, 224.

[9] See Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain, 23-29.

[10] Antony Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing in England– I: John Smith,” Print Quarterly 6:3 (September 1989): 251.

[11] Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing,” 245.

[12] Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing,” 245-246. Earlom was commissioned by Horace Walpole for his reworking of some of Smith’s plates.

[13] John Boydell, A Catalogue of a Collection of Prints: Now Engraving by Subscription, from the most Capital Paintings in England (London: Boydell, 1767).

[14] This particular impression is unique because Smith printed this sheet with what is most likely a red vermillion and iron oxide compound, rather than in gray scale using the more traditional black ink. This was probably a conscious aesthetic choice on Smith’s part, as there would have been no technical reason to choose the red tinted ink; rather, it was probably a way for Smith to lend further prestige to his own image that was first painted by none other than Godfrey Kneller.

[15] Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing,” 254, n. 30.

[16] Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing,” 254, n. 30.

[17] Griffiths argues that this was a difficult task because Smith would have had to buy back and reprint plates he engraved early on for other publishers and keep the supplies for all the private plates he made. See Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing,” 256.

[18] Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing,” 256.

[19] Horace Walpole, A Catalogue of Engravers who have been Born or Reside in England, second edition (London: 1786), 202.

[20] George Vertue, “Notebooks III,” Walpole Society 22 (1934): 113-114. Quoted in Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing,” 243.

[21] Vertue, 113-114. Quoted in Griffiths, “Early Mezzotint Publishing,” 243.

Cite this note as: Andrea Morgan, “Self/Portraiture and Artistic Exchange: John Smith and Sir Godfrey Kneller in Early Modern England,” Journal18 Issue 8 Self/Portrait (Fall 2019), https://www.journal18.org/4188.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.