Chanchal Dadlani and Holly Shaffer

This dialogue was prompted by the call to consider—and contest—the “long eighteenth century” as a theoretical and methodological frame, particularly in art history. As scholars of South Asia and Europe, we began to see that the notion of the long eighteenth century refracts when seen from the variant perspectives of two major competing dynasties in South Asia, the Mughals and the Marathas.

At its height, the Mughal empire (1526–1858) encompassed almost all of South Asia, stretching from the borders of Central Asia to the shores of present-day Bangladesh to the southern regions of the subcontinent. The Mughal emperors and their viziers developed a sophisticated, centralized state structure that spanned the early modern and modern periods. The Mughals enjoyed a premier position in global trade and diplomatic networks, with Persian nobles, Rajput kings, Italian gem merchants, and Jesuit priests all making appearances at the Mughal court. In the eighteenth century, however, the empire experienced seismic shifts. Its provinces grew increasingly independent, weakening or severing their ties with the imperial center. Simultaneously, regional Indian rulers and European trading companies, most notably the English and French East India Companies, gained a greater foothold in the Indian subcontinent.

Given the prominence of the Mughals, and their rule over centuries, they have often been the focus of scholarship. In the past ten years, though, scholars have begun to attend to other regional regimes that rose to prominence in the eighteenth century, among them the Marathas. The Marathas were a military elite from western India who rose to power under Shivaji Bhonsle, crowned king, or Chhatrapati Maharaj, in 1674. However, due to a series of succession crises in the eighteenth century—in part through the Mughal capture of Maratha leaders—Maratha rule passed from the kings to their ministers, the Peshwas, who moved the capital to Poona (present-day Pune) in 1730, and to Maratha generals who governed the lands the Marathas had conquered. In this period, the Marathas controlled much of western and central India, and as mercenaries, they exerted power over extensive terrains, including Mughal Delhi.

In focusing on the Mughals and the Marathas, we engage questions and themes that have concerned scholars in the fields of South Asian and Islamic art history for the past few decades, specifically around notions of decline, historicization, eclecticism, hybridity, and mobility. Far from staying limited to South Asia, however, our aim is to work from within the region of South Asia to expand the conversation on the global eighteenth century, revealing how an ostensible micro-art history can enhance a field-wide conversation.

Chanchal Dadlani: Given the historiography of South Asian art, the expectation would be that we begin this conversation with the Mughals. But we purposely wanted to de-center the Mughal empire in thinking about the eighteenth century and its possibilities. For this reason, we thought we would begin with a Maratha object that speaks to Maratha concerns and Mughal legacies alike: the Nana Fadnavis album, which was collated during the second half of the eighteenth century.

Holly Shaffer: Absolutely. The album sums up, to a certain extent, the intersection of the Mughals and the Marathas and the shifts in power that occurred in South Asia in the long eighteenth century.

If we think of the first half of the eighteenth century as a time when the Marathas established their regime, in part by fighting Mughal claims in western India, then the second half of the eighteenth century saw its reversal. In this latter period, the Mughal capital in Delhi was repeatedly plundered, and the Mughals leaned on the Maratha armies to maintain control of North India.

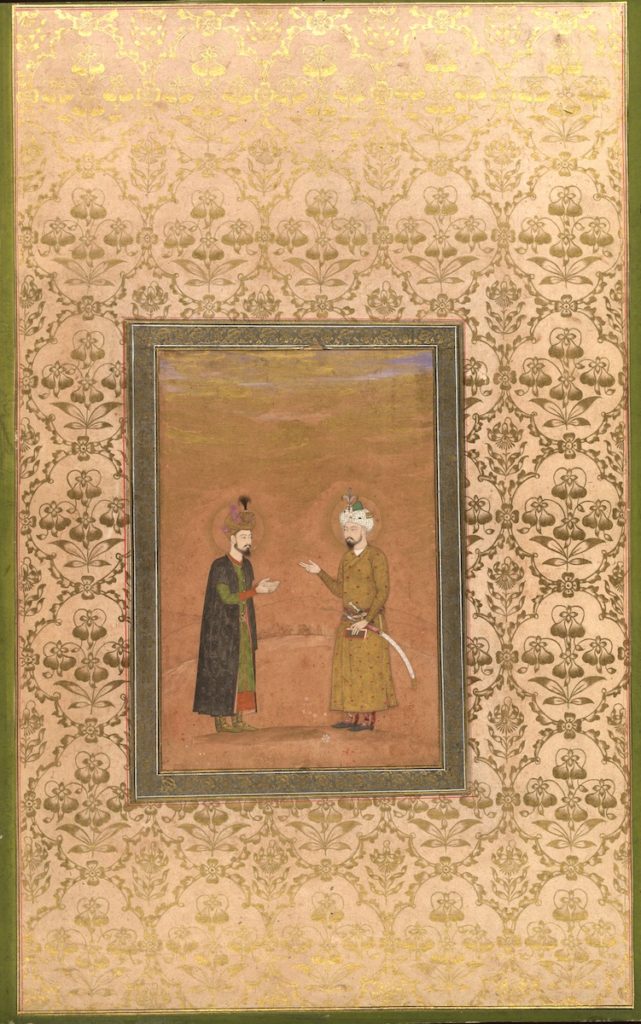

The album you brought up, Chanchal, is made up of Mughal paintings that were collected in the context of duress. One of the main administrators working for the Peshwa, Nana Fadnavis, assembled them with the assistance of the Maratha general Mahadji Scindia, who, from his capital in Ujjain, governed a large swathe of central India. Here is one page comprising a seventeenth-century Mughal painting that depicts the first Mughal emperor, Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, and his son, Humayun (Fig. 1).

But “collected” is too neutral of a term, and the album reminds us to think about the circumstances of collection. In this case, it is well documented that Nana Fadnavis sent agents to Delhi, Jaipur, and to well-established families in the Poona region to purchase or plunder paintings; he also commissioned paintings from artists and bought ones available on the market. The album itself was broken up sometime after Nana Fadnavis’s own defeat at the hands of the British and other Maratha factions in the early nineteenth century and it is now dispersed across collections in India and Europe.

CD: The moment of the album’s acquisition is so interesting to me, as is the presence of the Mughal portraits, because both circumstances embody a particular point in Mughal history. In the traditional historiography of South Asia, and especially in British colonial histories, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are seen as a time of expansion and consolidation for the Mughals, the eighteenth century is deemed a period of decline, and the nineteenth century is considered to mark the final downfall of the Mughals and the consolidation of British imperialism and structures of colonization. In recent years, the Mughal eighteenth century has been completely retheorized, but the old paradigm persists in significant ways.

HS: Yes, which is fascinating in comparison to the Maratha historiography where the eighteenth century is the period of ascension. The standard dates of the Maratha empire, from 1674 to 1818, map onto those of the European long eighteenth century, even if the specific years are slightly different. The dates of the Mughals, of course, extend both forward and back. How do you conceptualize the Mughal eighteenth century within that longer period?

CD: For me, the concepts that come to the fore are codification and historicization. If you look at the architecture of the eighteenth century, you see a prevalence of white marble, exquisite carving, and curvilinear architectonics. These elements were once associated with the emperor Shah Jahan, but they proliferated so widely over the course of the eighteenth century that they came to stand for the Mughal dynasty at large. Simultaneously, eighteenth-century buildings began to quote earlier monuments directly. For instance, the Fakhr al-Masajid (“Pride of the Mosques,” 1728–29) in Delhi appears as a miniature Jami‘ Masjid (the monumental congregational mosque that Shah Jahan built in Delhi, 1650-56) (Fig. 2). Through the interrelated forces of recursivity and reflexivity, architects and patrons created a signature Mughal style with strong historical associations—namely, with the political and cultural might of the seventeenth-century Mughals. What fascinates me most about this process is that it unfolded at a time when the Mughals had experienced dramatic political, economic, and military losses. These losses were the factors that long drove the “decline” narrative, but that narrative has masked the fact that Mughal visual forms retained currency, and in fact grew increasingly potent, over the course of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth, as territorial and economic control were contested. It was during the eighteenth century that certain forms became truly iconic of the Mughals. That’s why the inclusion of Mughal portraits in the Nana Fadnavis album interests me—these historical figures, and their representation, continued to matter.

HS: It makes perfect sense that in the eighteenth century the Mughals reflected on their past and historicized it, and that the Marathas drew on those Mughal histories as a model and to legitimate their own ascension. Do you see that across the arts?

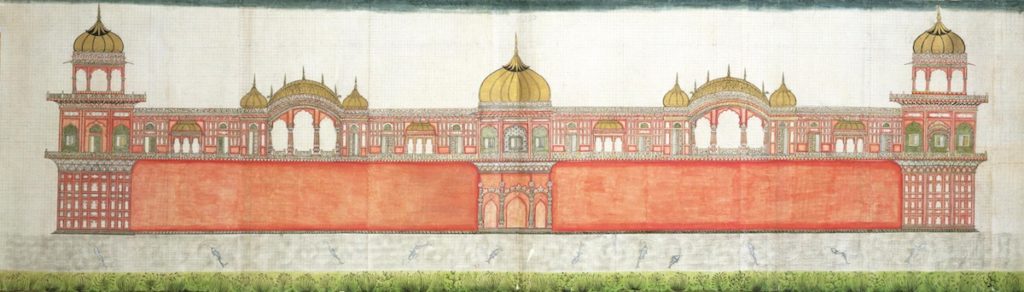

CD: Absolutely. One of the best examples is a series of large-format paintings from the 1770s called the Palais Indiens (Fig. 3). Although these are eighteenth-century paintings, they feature seventeenth-century buildings, and once again, they emphasize the monuments of Shah Jahan and a strongly standardized visual vocabulary. The paintings, which number over 25, are remarkable for their consistency: in painting after painting we see a near-uniform palette of red, white, and gold, reflecting the red sandstone, white marble, and golden domes of the built structures. We also see a standard architectonic vocabulary drawn from standing monuments—pointed domes, cusped arches, baluster columns, curved roofs and cornices—which is repeatedly used to “construct” the buildings on paper. The viewer is left with an impression of a highly standardized, codified style, similar to the impression they would gather from encountering architecture on the ground. And as was the case with the built environment, in painting, too, the process of representation is entangled with the process of historicization.[1] The Palais Indiens once belonged to Jean-Baptiste Gentil, a French East India Company officer who amassed a huge collection of Indian and Islamic manuscripts. He used the collection as a source to compose new works about India for varied French audiences, collaborating with Indian artists and translators to do so. Ultimately, he used the collection to position himself as an authority on the history and culture of the subcontinent.[2] So the impulse to codify and historicize is palpable in architectural and artistic projects and is enacted by South Asian and European agents alike.

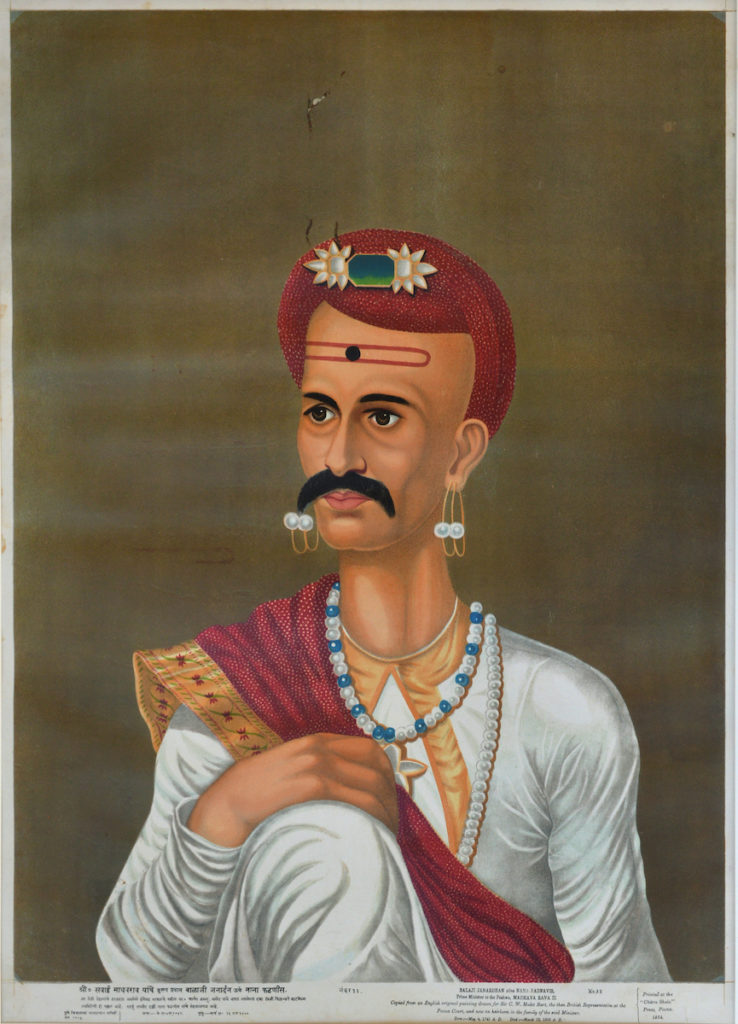

HS: With the Marathas you see a similar type of historicization, but it is in the nineteenth century and through the popular press. Unlike the Mughals, the Marathas didn’t create an identifiable style for their arts that visually codified their rule, but in the nineteenth century western Indian nationalists began to gather together Maratha materials in archives and historical societies and to print them, such as in the Chitrashala Press, which was founded in Poona in 1878. This is a complex history, and one which encompasses movements from the reformist to the extremist. I’ve included references for those who want to know more, but in brief, these printing and historical projects provided ways for western Indian nationalists to conceptualize the Maratha past on different terms than those documented in colonial accounts.[3] Some of these figures framed the confederacy of administrators and generals the Marathas pursued in the eighteenth century, such as the one of Nana Fadnavis and Mahadji Scindia, as a potential model for the unification of a nation independent from the British in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For example, this print is one of the first that the press produced, and it depicts Nana Fadnavis, whose album we referenced at the beginning of this conversation (Fig. 4).

CD: So it sounds like nationalism and its complexities are really driving periodization—the notion of what constitutes the eighteenth century—in that particular case. The question of what determines periodization is a significant one; we can also think about this in relation to political versus artistic events. With the Mughals, one could consider the long eighteenth century to begin with the death of the emperor Aurangzeb-‘Alamgir, in 1707, and consider 1803, when the British annex Delhi, as an endpoint. The other approach is to emphasize art and architecture in periodization, allowing us to foreground what happens in visual culture and let the visual shape historical inquiry. In this case, I might still begin with 1707, when we start seeing the proliferation of the reflexive Mughal style, and conclude at 1815 and the ‘Amal-i Salih of Akbar Shah II, which was the first imperial Mughal manuscript to include folios dedicated to architectural representation, keeping with the theme of historicization. Thinking of 1815 as an endpoint of the Mughal eighteenth century also intrigues me because the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, perhaps the most famous British building to reference Mughal architectural forms, also dates to this time. Bringing Brighton into the picture, despite its location in England and its own distinct history, opens up periodization not only in terms of time, but also in terms of place.

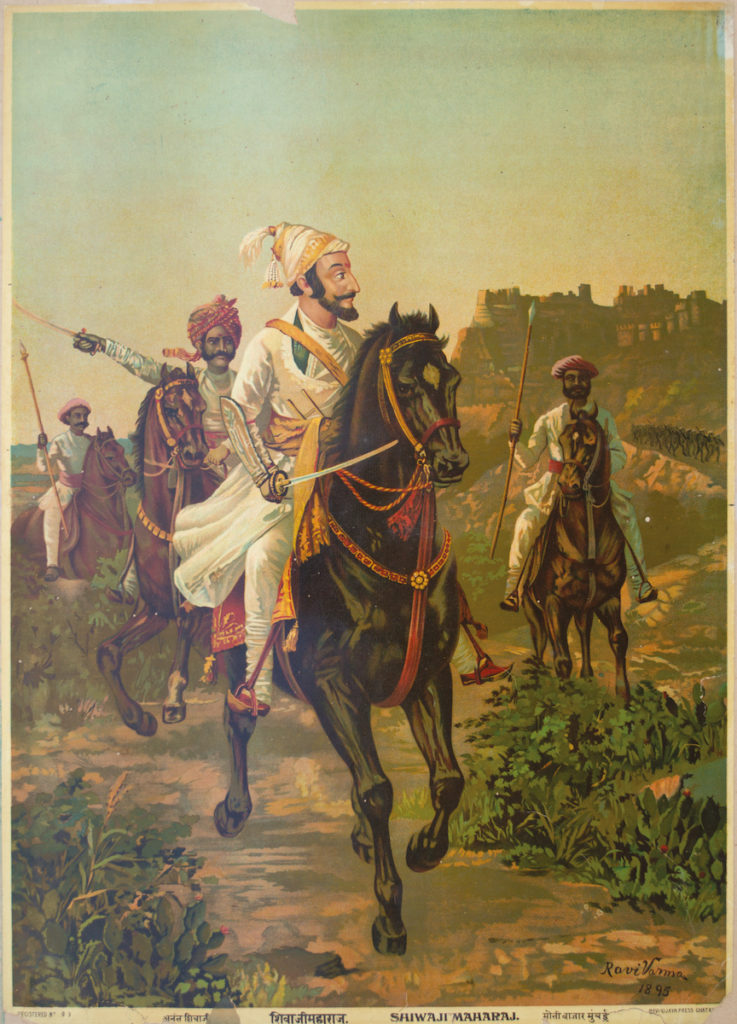

HS: It’s fascinating to think about periodization through art and architecture as well as historical events.[4] Keeping in mind your discussion of the “iconic,” the image I think of with the Marathas is a late nineteenth-century chromolithograph of Shivaji Maharaj, the first king of the Marathas, designed by the artist Raja Ravi Varma (Fig. 5), which became a key image in the western Indian nationalist movement, and continues to be a potent image today. Though produced in the late nineteenth century, the portrait actually returns us to the late seventeenth century. It therefore jumps over the rise and fall of the Peshwas, the ministers to the Marathas who ruled in their stead in the eighteenth century, to focus on the origin of power in the seventeenth century. So if I were to define the Maratha period by an “iconic” artwork known today, the significant dates would shift and actually occlude the eighteenth century. Whereas the political dates (1674–1818) and the dates of historicization in the late nineteenth century offer a different picture, one that focuses on the long eighteenth century.

But we could also think about artistic periodization as a way to highlight artistic process. The Marathas don’t have “iconic” monuments on the scale of the Mughals. Artists who worked for the Marathas often combined styles and compositions from regions and polities with whom the Marathas were politically engaged or over whom they exerted military control, such as the British or the Rajputs.[5] Rather than being iconic and recognizable, their arts are therefore stylistically mixed, eclectic, grafted, which speaks to a mercenary mode of production. This mixed approach, however, becomes another way to define the eighteenth century in the arts. Over a decade ago, in 2010, Nebahat Avcioğlu and Finbarr Barry Flood wrote in their introduction to a special issue of Ars Orientalis that “mobility, mercantile imperialism, and eclecticism” changed the practices of artistic production in the eighteenth century, and one of your essays on Gentil was in that volume.[6] It brings us back to an aspect of the Maratha eighteenth century upon which it would be interesting to expand. In the case of the Mughals, the Mughal eighteenth century sits within a centuries-long empire that precedes the eighteenth century and extends beyond it (1526–1858), whereas Maratha rule maps onto the European eighteenth century. But both the Mughal and the Maratha eighteenth centuries are connected to regional South Asian history as well as global politics, such as with the broader Islamic world and Europe.

CD: I’ve been thinking about the field of Islamic art history, which has also seen recent interrogations of the eighteenth century, throughout our conversation. Scholars have both reconsidered the nature of the eighteenth century on its own terms, and perhaps more implicitly, approached the eighteenth century in new ways as the field has moved more and more into the modern periods. A couple of examples come to mind. For one, the notion of decline long informed scholarship on eighteenth-century Ottoman visual culture, a period that has been recouped by scholars like Shirine Hamadeh and Ünver Rüstem, who have reframed the period in terms of new urban patterns and stylistic innovations.[7] And the relatively recent emphasis on the modern period in Islamic art history, the close examinations of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and the meaning of global modernisms undertaken by Anneka Lenssen and others, have also translated into a renewed interest in the eighteenth century and how it fits within the broader chronology.[8]

HS: That makes me think of Sonal Khullar’s framing of global modernism as one of “worldly affiliations” among artists.[9] Of course, this postcolonial concept specifically refers to affiliations intimately tied to the processes and politics of decolonizing, but I find that it resonates with work on the eighteenth century, where artists, collectors, even soldiers don’t often fit into neat cultural categories in part because there were so many multidirectional political negotiations and cross-cultural interactions. These were militaristic, cosmopolitan worlds. I’ve always found it productive to talk with you about the various circumstances of interaction between specific Indian rulers and specific French or British officials with whom they were negotiating for politics, business, or military purposes, and of course the amazing histories of artists who also served as intermediaries.

CD: That point takes me back to the Palais Indiens paintings, which are almost dizzyingly heterogenous (Fig. 3). The set is part of a French officer’s collection; it was executed by an Indian artist or artists; it employs Indian and eastern Islamic techniques such as the use of a hand-fabricated grid; and it adapts French conventions for rendering coordinated plans and elevations, which circulated in the subcontinent in the form of elevations and plans made by French East India Company engineers. These multifaceted paintings resulted from artistic and intellectual encounters that were made possible by regional and global mobilities, and they resist easy categorization. These characteristics are hallmarks of the Mughal eighteenth century, and perhaps the eighteenth century in South Asia more broadly.

HS: Maybe that is always a part of any discussion of periodization, the absolute resistance to it. It does seem that a hallmark of the eighteenth century is the inability to neatly or easily categorize it. As we know so well, this is embedded in the language used to describe the arts of the eighteenth century. For better or worse, these arts are often described as hybrid, mixed, or eclectic because of the assemblies of styles, peoples, and goods that undergirded the production and collection of art in this period. This characterization is stark in the case of the Marathas where their arts are tied to their wide-ranging diplomatic and military tactics, but as you’ve shown with the example of the Palais Indiens, I think it could also be applied to the Mughals even as they consolidated and historicized their arts.

CD: And crucially, despite intersections and echoes, these processes do not map neatly onto one another. At first, a conversation about the Mughals and Marathas might imply that we are examining micro-histories, or the regional history of South Asia. But on closer examination, the fluidity that we might expect of distinct “eighteenth centuries” from different parts of the globe is discernible even within a single region. In other words, we see the co-existence of multiple eighteenth centuries in South Asian art history.

HS: This conversation has made me imagine the long eighteenth century in multiple graphic forms, along the lines of how the author John McPhee explains his technique of drawing a visual storyline for his essays in Draft No. 4 (2017).[10] Your last comment made me think about history in concentric circles—not just as a macro-micro distinction, but a more graded one that has the potential to reshape histories that in turn ripple out from different regions. This also brought to mind a graphic network; at any point in time different groups, people or objects within South Asia, and outside of the subcontinent, can intersect or be connected. Then of course, there is the timeline—both the traditional historical timeline and the timeline of art history, seeing time according to political events and regimes and by way of artworks produced—that may simultaneously reveal intersecting or incommensurable bookends.[11] I hope our dialogue has reinforced how critical it is to conceptualize the long eighteenth century in a way that allows for the boomerangs of historicization.

Chanchal Dadlani is Associate Professor of Art History at Wake Forest University

Holly Shaffer is Assistant Professor of History of Art and Architecture at Brown University

[1]For more on these interrelated processes, see Chanchal Dadlani, From Stone to Paper: Architecture as History in the Late Mughal Empire (Yale University Press, 2018).

[2] On the Palais Indiens and the Gentil, Collection see Chanchal Dadlani, “The ‘Palais Indiens’ Collection of 1774: Representing Mughal Architecture in Late Eighteenth-Century India,” Ars Orientalis 39 (2010), 175–197, and Dadlani, “Transporting India: The Gentil Album and Mughal Manuscript Culture,” Art History 38:4 (2015), 748-61.

[3] On the history of western Indian historicism and nationalism, see Prachi Deshpande, Creative Pasts: Historical Memory and Identity in Western India, 1700–1960 (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2007); on the Chitrashala Press in particular, see Christopher Pinney, Photos of the Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India (London: Reaktion, 2004), esp. 46–58; and on the many strands of western Indian nationalism, see Rosalind O’Hanlon, “Maratha History as Polemic: Low Caste Ideology and Political Debate in Late Nineteenth-Century Western India,” Modern Asian Studies 17, no. 1 (1983): 1-33. For an in-depth discussion of this history in relation to art, see Holly Shaffer, Grafted Arts: Art Making and Taking in the Struggle for Western India, 1760–1820 (London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre with Yale University Press, 2022), Ch.5.

[4] Dipti Khera, one of the guest editors of this issue, has thoughtfully explored these themes in her book, The Place of Many Moods: India’s Painted Lands and Udaipur’s Eighteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).

[5] On Maratha arts, see Shaffer, Grafted Arts; and Holly Shaffer, “Towards a History of Maratha Painting in the Deccan,” in John Seyller, ed., Dakhan 2018: Recent Studies on Indian Painting (Hyderabad: Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art, 2020), 77–108.

[6] Nebahat Avcioğlu and Finbarr Barry Flood, “Introduction: Globalizing Cultures: Art and Mobility in the Eighteenth Century,” Ars Orientalis 39 (2010), 7–38 (11); and Dadlani, “The ‘Palais Indiens’ Collection of 1774.”

[7] Shirine Hamadeh, The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eighteenth Century (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007); Ünver Rüstem, Ottoman Baroque: The Architectural Refashioning of Eighteenth-Century Istanbul (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019).

[8] Anneka Lenssen, Beautiful Agitation: Modern Painting and Politics in Syria (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2020).

[9] Sonal Khullar, Worldly Affiliations: Artistic Practice, National Identity and Modernism in India, 1930–1990 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2015).

[10] John McPhee, Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2017).

[11] See the powerful timeline in Journal18: “Blackness, Immobility, & Visibility in Europe: A Timeline (1600-1800),” directed by Zirwat Chowdhury. https://www.journal18.org/nq/blackness-immobility-visibility-in-europe-1600-1800-a-collaborative-timeline/

Cite this article as: Chanchal Dadlani and Holly Shaffer, “The Mughals, the Marathas, and the Refracted Long Eighteenth Century: A Dialogue”, Journal18, Issue 12 The ‘Long’ 18th Century? (Fall 2021), https://www.journal18.org/6054.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.