Sana Mirza

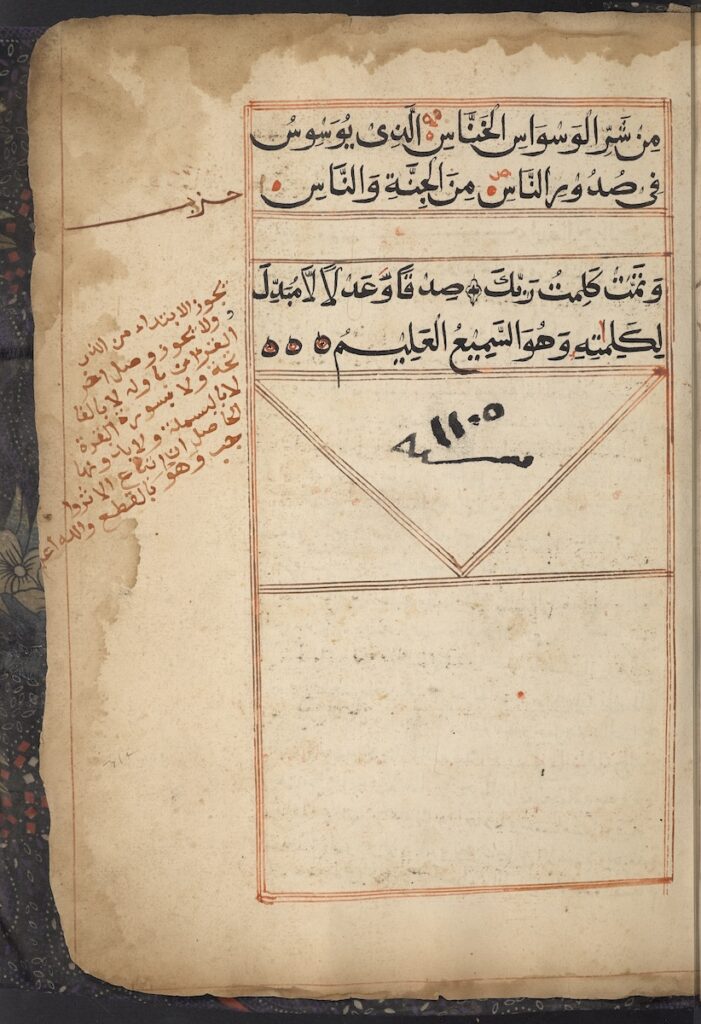

A Qur’anic manuscript in the collection of Princeton University Library (PUL) reveals a fascinating history of the interconnections between commercial and artistic centers within the eighteenth-century Indian Ocean, and the complexity of identities and regional styles of manuscript production during a period of increasing transoceanic empires and networks. Acquired by PUL in 2022, the manuscript was produced in Harar, in present-day Ethiopia in the last decades of the eighteenth century. A later note identifies the manuscript was endowed by a Hassan bin Adojo in honor of his mother Fatima Shāshū, in Diu, then a major Portuguese-controlled port off the coast of Gujarat, India (Fig. 1). Hassan’s identify and biography remains elusive. His father’s name of Adojo has been thought to imply West African ancestry, but this is difficult to substantiate.[1] This article takes the manuscript as its point of departure in order to explore the circulation of manuscripts between Harar and other regions within the Indian Ocean and the merging of local traditions of manuscript production in a single codex.

Harar has been one of the major centers of Islamic learning in the Horn of Africa since at least the thirteenth century.[2] Its long history of religious and military leaders has led to the construction of the hundreds of mosques and tombs radiating throughout the city and its surrounding countryside, leading to the city’s distinctive reputation as a city of saints (madīnat al-awlīya’).[3] Against this backdrop, the large-scale production of manuscripts in the city is perhaps unsurprising. Hundreds, if not thousands, of manuscripts were produced in the city between the late seventeenth century and late nineteenth century, during the period of the Harari Emirate (1056/1647–1292/1887). While these manuscripts cover a range of subjects, they are largely religious in nature and written in Arabic or Harari, a local language written in Arabic script. The wealth of historical information preserved within the codices, from colophons to endowment notices and ownership transfers, allows for rare opportunities to contextualize intellectual histories, sociological structures, religious practices, and artistic developments. Whereas many of these manuscripts are still preserved in Ethiopia, including in mosques, tombs, family collections, and museums, others are now scattered in collections around the world, a phenomenon that may reflect patterns of circulation that have pre-modern roots, as we shall see.[4]

Traces of Harari texts circulating in Western Arabia and Gujarat are evident as early as the late sixteenth century, laying the groundwork for regular exchanges and the convergences of manuscript cultures across the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. One of the earliest histories of Harar, the Tuḥfat al-Zaman (Wonder of the Time)written by Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Qādr Jizāni, appears to have been composed specifically to be copied, a rallying cry to advertise the success of military campaigns led by Imam Aḥmad Gragñ (c.1506- 1543) and encourage foreign support. It was likely in the Hijaz (Western Arabia) or in Gujarat itself that Haji al-Dābir (b.1539–40) encountered the text and chose to copy it within his early seventeenth-century history of Gujarat.[5] The text might have felt particularly relevant for Haji al-Dābir: his patron was one of the individuals captured by Imam Aḥmad’s troops, enslaved and taken to India where he rose as a military leader.[6]

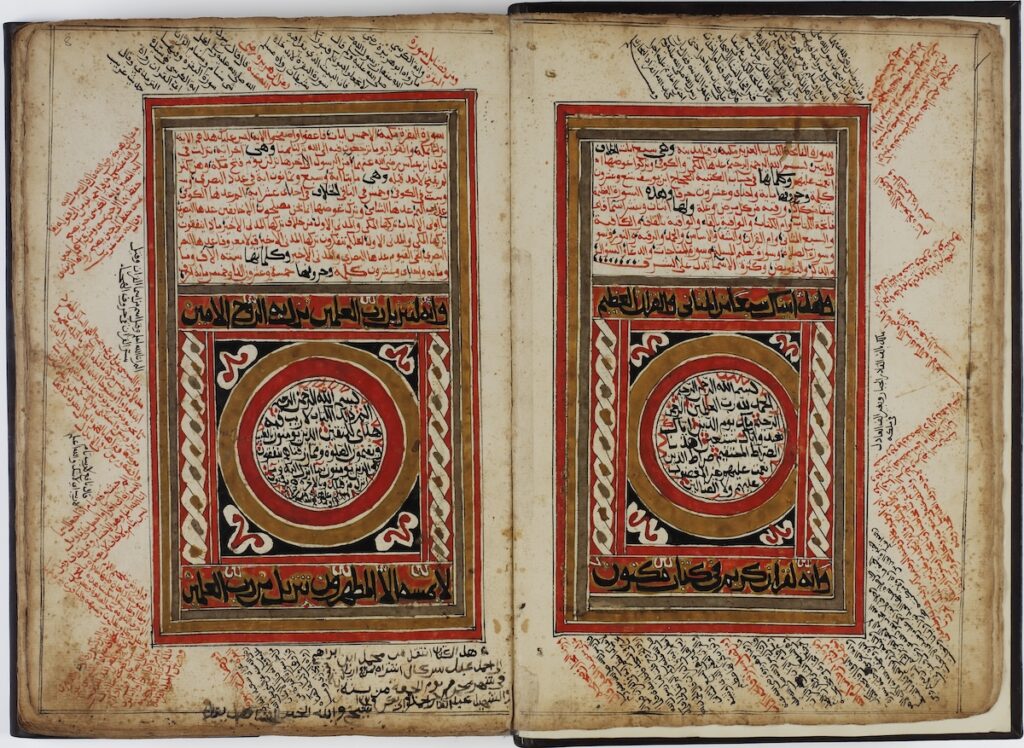

These circuits of interchange across the Red Sea and Indian Ocean were multidirectional and helped shape stylistic development within Harar, where scribes and artisans appear to have actively engaged with transregional trends, to create localized modes.[7] The Princeton manuscript is a rare testimony to the appeal of Harari Qur’ans outside of Harar. Only one other example of a Harari manuscript is currently known to have left the Horn of Africa before the twentieth century: a Qur’an manuscript now in the Khalili Collections in London. The manuscript was copied in Shawwāl 1162/September–October 1749 by Haji Saʿd ibn Adish ʿUmar Dīn, and made its way to Zanzibar by Ṣafar 1255/April–May 1839 (Fig. 2). At least four owners from between 1813 and 1873 are noted within the manuscript including several who can be linked with Oman, as described by Tim Stanley.[8] Juxtaposing this Qur’an with the Hasan bin Adojo manuscript allows for a fuller picture of the wider relationships between regional centers in East Africa and Harar’s interconnections within networks that stretched from Eastern Africa to South Asia.

Developed for a Harari Market

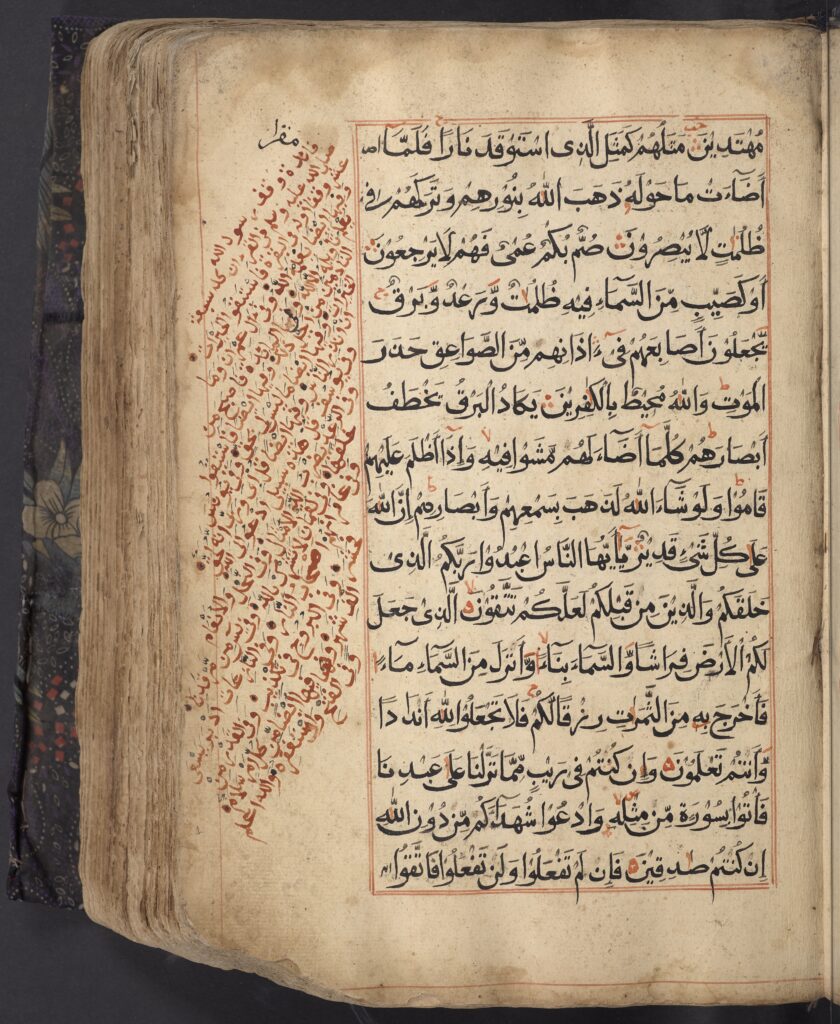

In its calligraphic, decorative, and material dimensions, the Hassan bin Adojo manuscript is typical of late eighteenth-century Qur’anic manuscripts produced in Harar for scholarly circles, which often contain vestiges of artistic interchange. It is a single volume measuring 33 × 23 cm with 15 lines of Qur’anic text per page. The text is carefully copied on two types of Italian laid paper bearing the watermarks of Valentino Galvani, Friuli, in particular the Tre lune (three moons) watermark and initials V.G. This kind of paper is found in Ottoman documents from as early as 1678 and in Egyptian manuscripts from the end of the eighteenth century, but the earliest dated example in an Ethiopian manuscript is from 1788. [9] The second paper also contains the initial V.G. but with a moonface in shield watermark.

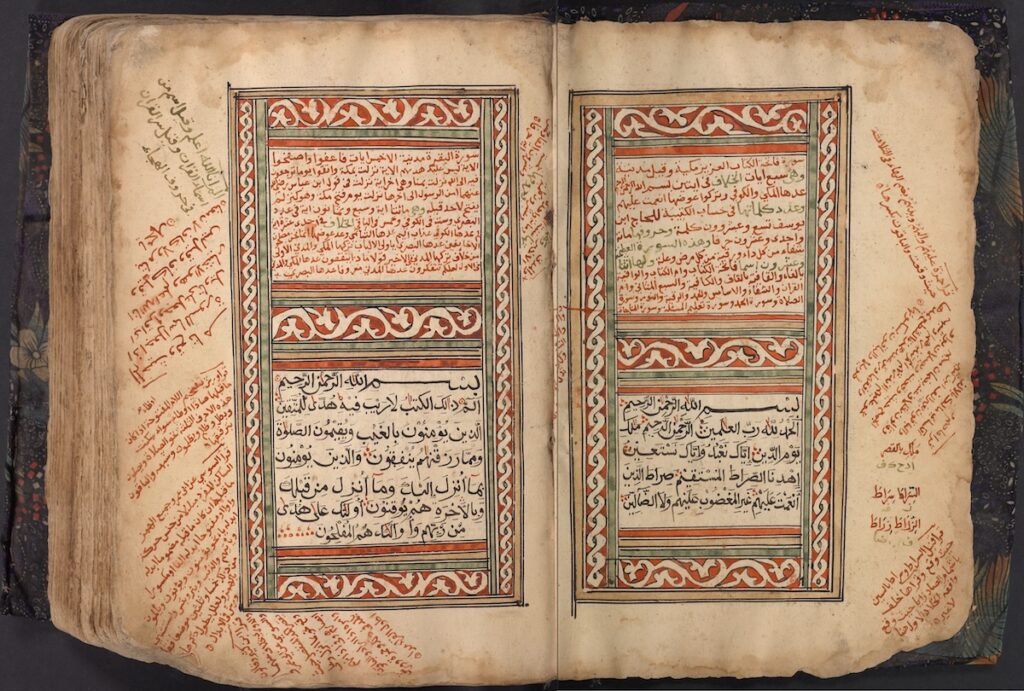

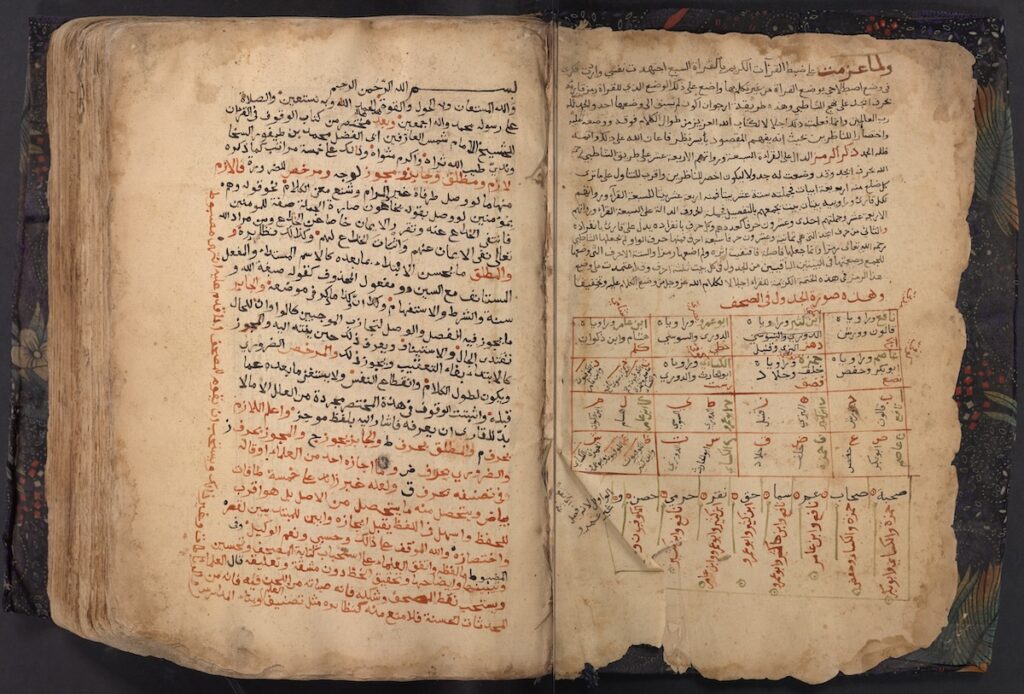

The intended scholarly audience of this Qur’an is clear from the large size as well as ample margins and distinctive textual layout that allows for the presentation of additional information. The major features of these scholarly Qur’ans are best observed on the incipit page (see Fig. 1). Colorful lines and vegetal scrolls divide the mise-en-page into several zones. Within the central block, the lower portions contain the first chapter (sura) of the Qur’an, Sūra al-Fātiḥa (The Opening), and the first five verses of the second, Sūra al-Baqara (The Cow) within an elaborate composition, which practically divides the different types of content within specific zones. The upper portion features information about each chapter, including the number of verses and words contained within the sura based on the different canonical recitation styles. Lines of yellow, green, and red, as well as bands of white vegetal or twisted motifs against red grounds emphasize these separate zones. The final feature is the marginal notes: the wide borders of the page are filled with short text in red and black expanding on recitation differences in various orientations. These large single-volume manuscripts often begin with texts on the proper recitation (qira’at) and orthography of the Qur’an, quoting the major twelfth-century Andalusian authority on Qur’anic recitation, Imam al-Shāṭibī (d.590/1194).[10] This paratextual material unpacks different ways of reading the Qur’an aloud, for instance the lengthening of syllables, when letters assimilate, and where to pause for the end of verses or vowelization options.[11] It can also include a chart listing the number of verses, words, and letters in each chapter. The longest and earliest known example of al-Shāṭibī’s text is found in a Harari Qur’an copied in 1120/1708.[12] This information is replicated in the first two pages of the Princeton manuscript, but it is more abridged than is typical for Harari Qur’ans (Fig. 3). In their compilation, the manuscripts are a one-volume library, the ultimate textbook presenting the Word of God and the tools to recite it beautifully.

This format within Harari Qur’ans became increasingly popular from the second half of the eighteenth century onwards, and more standardized in terms of size, script, and color schemes. The depth and breadth of this paratextual information and the specificity of its content suggest the manuscripts were destined for learning environments in Harar. The manuscripts are among the largest-sized ones, and the different orientations of the marginal text might imply a group gathered around them. The didactic format may have been particularly desirable at this moment due to greater conversion to Islam within the region and the growth of religious schools.[13]

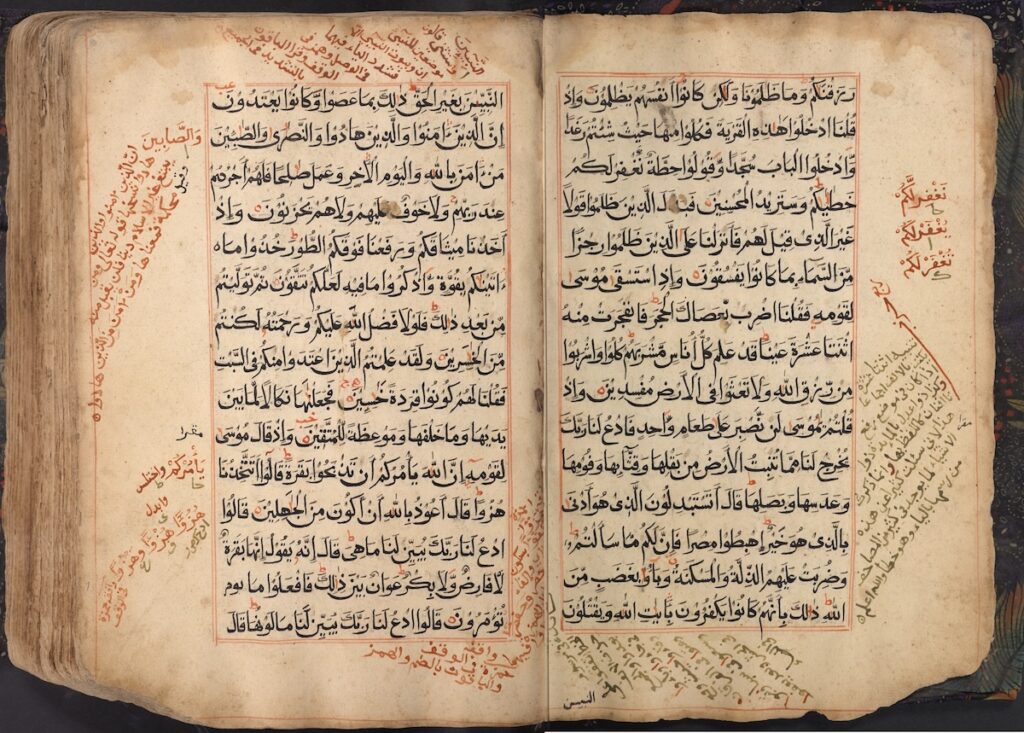

The calligraphic script of the Hassan bin Adojo manuscript is typical of a regional Harari naskh. This script is characterized by thin diacritical marks, which are often placed horizontally, and by thicker and slightly wedge-like sublinear extensions juxtaposed with thin connectors that developed over the course of the eighteenth century.[14] These distinctive features of the script subtly retain some historicizing features more commonly found in biḥārī script, which was favored for Qur’ans from the Indian subcontinent and was known for its juxtaposition of thin vertical and thick extended horizontal elements (Fig. 4).[15] These biḥārī-esque features are found in a variety of regional naskh scripts across the Indian Ocean.[16] Both the scholarly format and calligraphic script of the manuscripts are indicators of Harar’s position within cross-regional networks. The city’s critical location along major trade routes leading from the Ethiopian highlands to the Red Sea coast port of Zaylaʿ led to larger connections to Southern Arabia and the wider Indian Ocean world. In particular, Harar was a major exporter of coffee, a drink whose popularity was skyrocketing in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, increasingly drawing Harar into long-distance trade networks.[17]

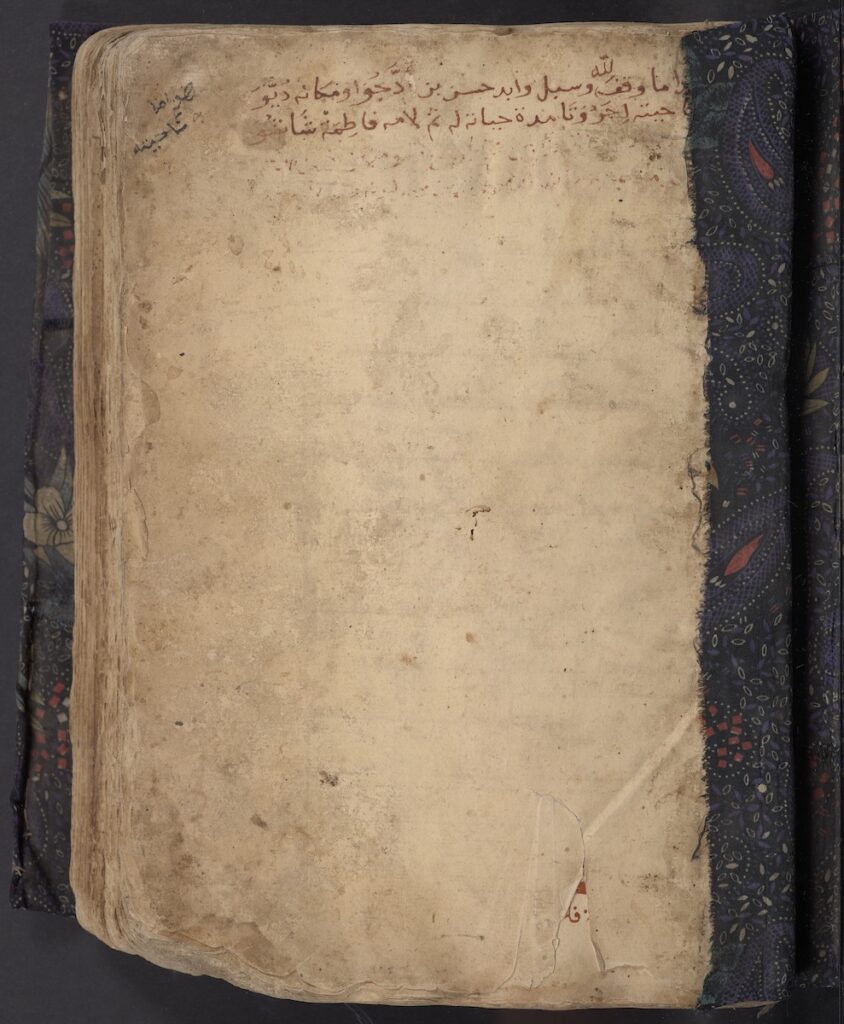

Whereas many of the Harari Qur’anic manuscripts have extensive colophons and waqf (endowment) notes, this manuscript does not and, therefore, its exact date of copy is unknown. The scribe left room for a colophon but did not write one. Similar empty colophons are found in a few other Harari manuscripts, all dating to the late eighteenth century or nineteenth century, suggesting that this may have been an intentional practice and could relate to market practices. A later hand has written in a date of 1105/1693–4, which is clearly in a different ink and a larger pen than the rest of the manuscript (Fig. 5). The stylistic details unpacked above, however, suggest that this date is unreliable and that the manuscript was copied close to a century later, at the end of the eighteenth century. The endowment note is on the first page of the manuscript. While it appears to have been partially erased and incomplete, the inscription is legible, clearly showing the name of Hassan, the place of Diu, and the name of Hassan’s mother, Fatima al-Shāshī. The scribe appears to be unfamiliar with Hassan’s father’s name (Adojo) as well as his mother’s because both names are vowelized (i.e., the short vowels are indicated) while the remainder of the text is largely consonantal, as would be expected (Fig. 6).

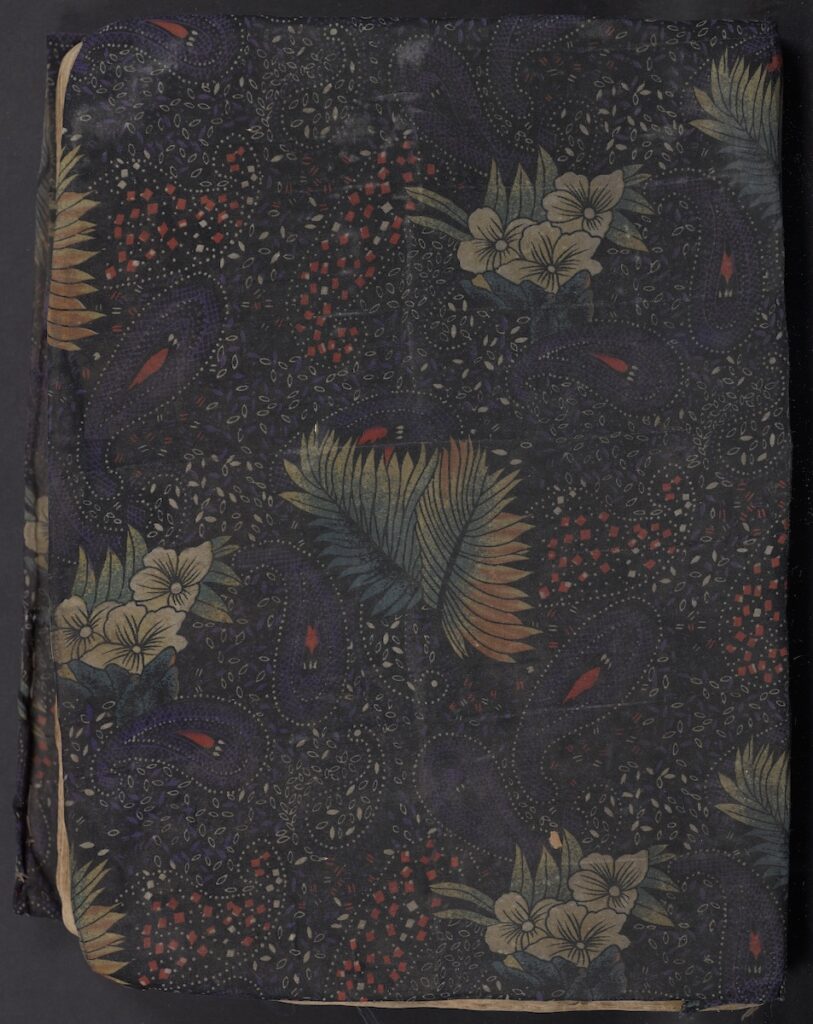

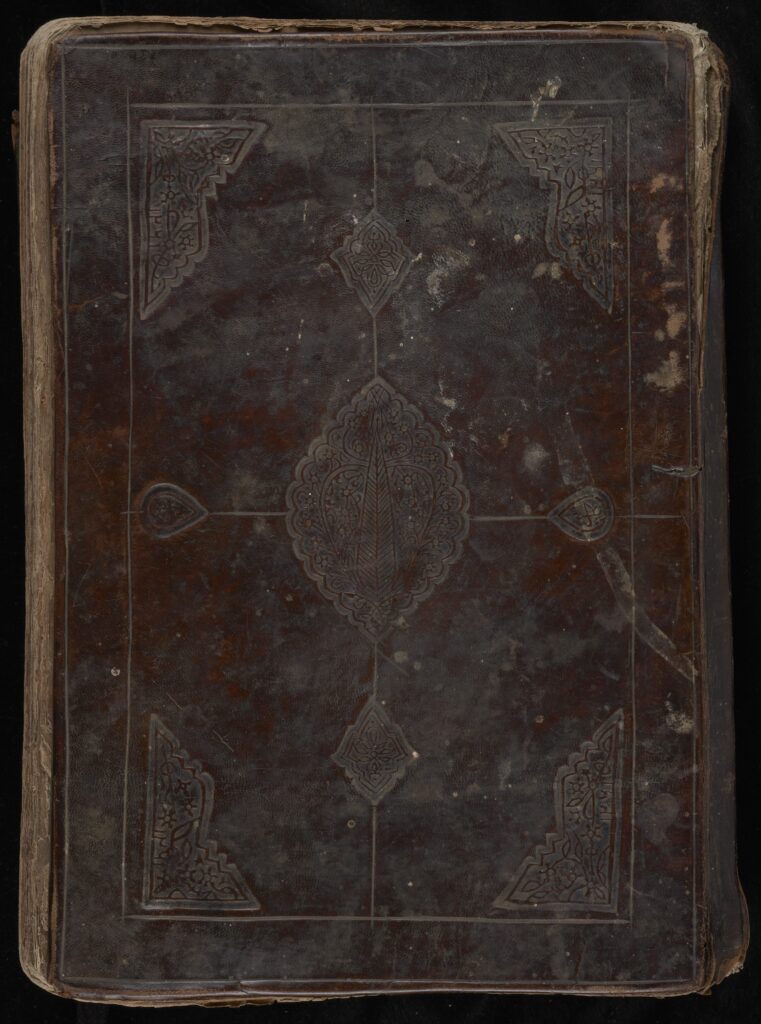

The one feature that is atypical is the current binding, which is not original but composed of corrugated cardboard covered with a floral-patterned polyester cloth. This binding dates from the late nineteenth century, at the earliest, but is likely from the twentieth century (Fig. 7). The cloth wrapper is not connected to the manuscript but serves more as a folder.[18] The spine of the text block has also been lined with the same patterned fabric but may be covering a historic liner (see Fig. 6). Yasmeen Khan observed there appears to be cloth beneath the current textile; this type of binding is found in several Harari Qur’ans within the Library of Congress which have a leather or cloth lining the text block spine and a detached leather binding.[19] In her extensive codicological study, Anne Regourd has also noted gauze used on Ethiopian Islamic manuscripts to protect the block of quires; this allowed manuscripts to be fixed in provisional bindings and for binding to be reused.[20] This peculiar wrapper therefore might preserve the style of a more historic wrapper and also help pinpoint when the manuscript left Harar.

The Harari manuscripts were conceived in quires, unlike the loose-leaf manuscripts produced in West Africa. A relatively uniform Harari stamped leather binding tradition appears to have begun by the late eighteenth century and flourished into the nineteenth century. These envelope bindings have relatively standard features (Fig. 8). [21] The presence of bookbinders in Harar is remarked on by travelers like British adventurer-diplomat-writer Richard Burton (1821–90) and by Khedival Egyptian military leader Major Mohammed Moktar, who occupied Harar in 1875.[22] Regionally, there is evidence for a preference for Harari bindings. Hassan Muhammad Kawo has argued that scribes may have taken their manuscripts to Harar to be bound. He has identified two manuscripts with dated Harari-style bindings that were copied by non-Harari scribes in Wallo in north-central Ethiopia. One was completed in 1189/1775 and bound in 1190/1776, and the other was completed in 1252/1837 and bound in 1261/1845.[23] The gap between the text’s completion and the binding indicates that manuscripts were not immediately bound after they were copied or may have had more ephemeral intermediary solutions, as could have been possible with the Princeton manuscript. It seems doubtful that the Hassan manuscript would not have acquired a leather binding if it remained in Harar into the nineteenth or twentieth century, at the height of the Harari binding tradition, and it is therefore likely the manuscript left Harar in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century.

Destined for Abroad

The dense trade networks of the Horn of Africa, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean have long resulted in the transfer of materials, manuscripts, and artistic styles.[24] Furthermore, the use and reuse of manuscripts could occur over centuries.[25] Travelers were known to carry their own manuscripts abroad. Several examples of foreign manuscripts within Ethiopia exist, such as a Yemeni ambassador to the Ethiopian Solomonic court in the seventeenth century or Burton who gave away a “cheap Bombay lithograph” Qur’an during his travels in Ethiopia in 1854.[26] Other Qur’ans of unknown provenance also remain preserved within Ethiopia, such as a sixteenth century Indian Qur’an in biḥārī script which was found within the complex dedicated to Sheikh Hussein in Bale; an eighteenth-century Ottoman-style Qur’an now in the Sherif Harar Municipal Museum, and a potentially Omani or Western Indian Ocean Qur’an now in the Institute of Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa University.[27] However, evidence of Harari Qur’ans traveling beyond Ethiopia is more rare and the exact route of this manuscript remains elusive, though it likely traveled along trade routes to Zaylaʿ, the principal port connected to Harar, and then onwards to Somalia or Southern Arabia.

This route eastward appears consistent with the Khalili Qur’an’s trajectory. Completed in 1162/1749, the manuscript contains a note of ownership transfer dated 1229/1813–14 and mentions the manuscript was bought for 100 riyals. The use of riyal as currency refers to wider transoceanic trade networks. In this context, riyal likely referred to the Maria Teresa Thaler silver dollar. This Austrian coin was first minted in 1741, and its use skyrocketed, particularly in the Hijaz, Yemen, and Oman into the twentieth century; it was particularly associated with the coffee trade.[28] While it seems likely that the coins were circulating at least in the Christian Ethiopian court by 1805,[29] there is less known about its use in Harar until the 1840s. While the Harari sultans minted their own coins, Thalers were used alongside the local currency according to foreign travelers. Harari coins were also found on the Somali coast.[30] Burton used riyals while traveling from Zaylaʿ to Harar several decades later in 1854–55.[31] As a comparison, the Ottoman-style Qur’an in the Sherif Harar Museum also has a transaction note, dated 1248/1832–33, but the currency used is ashrafī , the local Harari currency. It does seem possible, if not probable, that the Khalili manuscript had already left Harar by the time of this 1813–14 transaction. Furthermore, it has been argued that the Thaler was not common in the Hijaz by 1814, though it was in Yemen and in Red Sea ports.[32] If the manuscript had reached southern Arabia by 1813–14, it then passed to Omani natives who resided in Zanzibar by 1255/1839.[33] This period was one when many merchants, particularly those from Gujarat, relocated from Yemen to Oman, where they found more economic opportunities.[34]

The use of an Austrian currency for the coffee trade further highlights the region’s interconnectedness and the rise of transoceanic empires which provided the structures for the forced and voluntary movement of people, goods, and artistic styles. Yasuyuki Kuriyama argues that architecture in nineteenth-century Ethiopia displays a strong similarity to that built in Djibouti, Zanzibar, Massawa, or Aden that could be described as a “British Indo-colonial” style or an extension of the Red Sea architectural style described by Nancy Um.[35] Diu connected to ports of Goa, Cochin, Malacca, Aden, Jeddah, Kilwa, Meline, Mombasa, Sawakin, and Zaylaʿ.[36] Gujarati merchants were particularly active in the southern Red Sea as well as between Yemen and Oman and Zanzibar.[37] By 1730, Portuguese ships from Diu transported dozens if not hundreds of Indian migrants to Southern Yemen and probably Ethiopia, setting the stage for a two-way exchange of goods and movement of people. [38] Likewise, Scott Reese’s examination of nineteenth-century British Aden brings to light the exponential growth of merchant communities within the city, which would have facilitated the greater circulation of material goods. Furthermore, wealthy patrons, including merchants from Egypt, Iraq, and India, often chose not to endow new mosques and shrines but to revive older ones.[39] The preference for endowing older manuscripts may also reflect their status within a baraka-centric cosmology, in which the historicalness of a site or building, or in this case manuscript, was associated with the transmission of blessings.[40] The Khalili inscription underlines how valued the manuscript would have been. Though writing a few years later, Burton mentions in Zaylaʿ a large sheep costs 1 riyal and a camel about 10 riyals.[41] Burton’s account gives a rough benchmark of the buying power of a riyal and, therefore, of the magnificence of the Harari Qur’an, which would then be equivalent to 100 sheep or 10 camels outside its homeland. The forged colophon of the Princeton manuscript may also have been a historic attempt to age the manuscript and increase its market value.

The heritage of Hassan’s mother may make Yemen or Somalia an even more tempting theory as an intermediary point in the circulation of the manuscript. Her name is given as Fatima Shāshū, a name that is still common in Somalia and Yemen today and possibly related to al-Shāshī. [42] It refers to the Shanshiya clan, which is often linked with the Banadir costal region of Somalia where the cities of Mogadishu and Barawa are located. Perhaps the most famous Shāshī was Shaykh Sufi ʿAbd al-Rahman ibn ʿAbdallah al-Shāshī (1828–1904), a major Qādirī shaykh attributed with spreading the tariqa (Sufi order). Relevant to both the Princeton and Khalili Qur’ans, Barawa went from Portuguese control to being allied with the Zanzibar Sultanate at the end of the eighteenth century.[43] Soon after, these two manuscripts made their way to Zanzibar and Portuguese Diu respectively. In the mid-nineteenth century, another Shāshī is listed as an owner of a Qur’an in Harar that is now preserved in the Sherif Harar Municipal Museum, offering evidence of the widespread presence of the Shanshiya clan in the Horn.[44] We lack more details about Fatima and Hassan, but women were major patrons of manuscripts within Harar. Either of them may have inherited the manuscript or purchased it in Somalia, in Yemen, or even in Harar or Gujarat.

Adapted for New Tastes

The distinctive format of this Qur’an may have been part of its desirability as an export luxury object, but its adaptation as it journeyed eastward reveals the level of integration of Harari’s artisans in long-distance artistic milieus—and how a manuscript that reflected specific dynamics within Harar could speak to wider Indian Ocean concerns and motivations. The marginal glosses and additional materials within the Princeton manuscript align conceptually with Harari traditions but embedded within the paratextual material are different discursive concerns, which might relate more to its eventual context in Diu.

There were at least two stages of adding paratextual commentary within the Princeton manuscript. The first was contemporaneous with the copy of the Qur’anic text, when the scribe left room for the elaborate sura headings and then carefully included the additional information. These descriptions are copied almost word by word and align completely to the text found in other Harari Qur’ans. Within the larger corpus of Harari Qur’ans, some manuscripts only have these extended introductions, and in others this “base” was added on with up to two additional levels of annotation programs. It seems likely the Qur’an was originally designed to have only the base level of paratextual material and minimal marginal annotations. The rest of the annotations may have been added after the manuscript left Harar.

The introduction to the manuscript and the marginal commentary do not align with standard Harari practices. While other Harari Qur’ans also begin with explanations on the recitation styles principles of Imam al-Shāṭibī, this text is always carefully copied and part of the original conception of the manuscript. In Hassan’s manuscript, the text appears to be written by different hands than those who copied the Qur’anic text or sura introductions. The lines are not straight, nor are the pages framed (see Fig. 3). The text is the shortest version of the recitation principles represented in the known manuscripts from Harar, and the chart aligning the symbols that will be used to represent the different qirāʾāt schools is also not regularly found in other Harari manuscripts. More peculiarly, the text on the left page (see Fig. 3)focuses on the allowable pauses when reciting the Qur’an, a concern that does not appear in the other Harari Qur’ans either. It summarizes the principles of Imam Muhammad ibn Tayfūr al-Sajāwindī (d. 560/1165), who was famous for developing a system that is still used today, particularly in South Asia and Turkey.[45] Additionally, this later scribe has added fāʾida or beneficial notes. One such note mentions the points where the Prophet Muhammed stopped during his recitation of the Qur’an (Fig. 9).[46]

In addition to these discrepancies in content, the marginal notes also differ from those found in other Harari Qur’ans in terms of their format. The scribe has rewritten the words with different spelling or diacritics and uses a shorthand to signal to which school this reading adheres. In figure 4, this can be seen on the upper right and lower left, where the different pronunciations are written in red with a single letter in a light black below them. However, in all the manuscripts still within Harar annotations always spell out the different pronunciations saying which diacritic should be read for which letter and listing the full name of the schools of recitation.

The content and format of the marginal notations and the introduction summarizing Imam al-Sajāwindī’s treatise thus points to another intellectual milieu outside of Harar. More research is needed to unpack the discursive networks reflected within the marginal glosses and paratextual materials and to localize these different traditions over centuries. Islamic juridical discussions around how to present paratextual material date to as early as the eleventh century and coincide with the beginning of the incorporation of translations and other material within Qur’anic manuscripts. Abū al-Muzaffar Shāhfūr Isfarāʾīnī (d. 1079), an exegete of the Shafiʿi school of Sunni jurisprudence, has argued that paratexts should be distinguished from the Qurʾanic text by color or script.[47] This opinion may have guided the presentation of paratextual material, as this distinction appears to have been put in practice over a long temporal and geographic span, from Cairo to Aceh into the nineteenth century, when printed copies of the Qur’an also included marginal commentaries. The extent of the religious scholarship and nuanced material presented within these volumes makes it likely that they were produced for religious institutions. The earliest annotated copies of the Qur’an arose during widespread architectural patronage not only by sultans but also by viziers and other elites in the twelfth and thirteenth century.[48]

The paratextual material highlights the overlapping networks and concerns of scribes and patrons across the Indian Ocean. In format, the glosses of the Hassan manuscript are most similar to South Asian Qur’ans written in biḥārī script as well as those in the Sulawesi diaspora style from Southeast Asia.[49] Annabel Teh Gallop has argued these Southeast Asian Qur’ans developed in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, the same moment Harari scribes also began to introduce glosses and paratextual materials to their Qur’ans.[50] Whether directly or indirectly, the development on opposite sides of the Indian Ocean of highly specialized Qur’anic manuscripts speaks to shared interests and the crystallization of networks of Muslim scholars.[51] This attention to qirāʾāt probably lay beyond the concern of average Muslims but was of great interest to scholars, as other Indian Ocean studies have shown. In Southeast Asia, Qurʾanic studies became more prevalent after the seventeenth century, with many commentaries and treatises increasingly copied in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This phenomenon is often associated with the spread of Sufism, which created a large audience of religiously well-educated individuals.[52] Michael Feener and Michael Laffan also identify the importance of the Qādiriyya ṭarīqa, the Sufi order founded in Iraq by Shaykh ʿ Abd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī (d. 1166), and its network in the eastern Indian Ocean, and the movement of scholars, particularly from Java, during the eighteenth century.[53] In the later glossing of the manuscript, Hassan’s Qur’an not only displays the shared artistic and discursive concerns that reflect the Harari artistic milieu, but also demonstrate how pervasive and permeable these concerns about correct reading practices were across the Indian Ocean.

Conclusion

The interconnectivity of the Indian Ocean regions during this period leaves open other possibilities that cannot be discounted. This raises an important question: could the manuscript have been written by a Harari scribe based elsewhere? In their work on Southeast Asia and Arabia respectively, Gallop and Regourd have highlighted some of the complexities of visual and material analysis without historical documentation in this period of burgeoning globalization. They note Southeast Asian calligraphers and illuminators copied Qur’ans in their distinctive Acehnese and Patani styles while based in Arabia. Additionally, a Yemeni calligrapher from Zabid in Yemen copied a Qur’an in Sumatra, Indonesia, which was decorated in Southeast Asian styles.[54] The growth of empires—both regional and European—also changed the dynamics of the Indian Ocean as a whole, aiding in the circulation of new artistic forms in the eighteenth century. This increased circulation allowed for the permeability of tastes and the layering of practices specific to different regional traditions but also transcending them. As I hope to have demonstrated, Hassan’s manuscript calls for the need to consider these manuscript cultures in light of each other, for awareness of the greater interrelations of centers of African Islamic manuscript production as well as the interconnections between the manuscript cultures of eastern Africa and the wider Indian Ocean world beyond.

Sana Mirza is an independent art historian based in Washington, D.C., specializing in Islamic manuscripts from Ethiopia and their Red Sea and Indian Ocean milieus

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Yasmeen Khan, Finbarr Barry Flood, Prita Meier, Hermann von Hesse, and the anonymous peer reviewers for their feedback and advice. I am grateful to Deborah Schlein and Princeton University Library, as well as Suzanne Akbari, Melissa Moreton, and the Hidden Stories: New Approaches to the Local and Global History of The Book initiative for facilitating my study of this manuscript. I am also deeply indebted to the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Sherif Harar Municipal Museum, Khalili Collections, and Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

[1] https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/99125500439306421 (accessed 10/4/2024). The manuscript has been completely digitized. It was acquired from the antiquarian bookseller N.G. McBurney, who believes the manuscript reached Europe by the second half of the twentieth century; it was purchased from a Swiss private collection, but specific information is not publicly available at this time; see N.G McBurney, Early Printing & Manuscripts of the Islamic World: List VIII (2022), 4-7. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d235d09229b500001711584/t/63d8f5ae2695966393597cf6/1675163055097/List+VIII+-+NGMcBurney.pdf

[2] Recent archeological excavations have suggested much of the modern city dates to the sixteenth century at the earliest; see Timothy Insoll, “First Footsteps in the Archeology of Harar, Ethiopia,” Journal of Islamic Archaeology 4, no. 2 (2017): 189–215.

[3] Roman Loimeier, Muslim Societies in Africa (Indiana University Press, 2013), 172; Ulrich Braukämper, Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays (Lit Verlag, 2002), 115–18.

[4] For an overview of collections within Ethiopia, see Hassen Muhammad Kawo, “Islamic Manuscript Collections in Ethiopia,” Islamic Africa 6 (2015): 192–200.

[5] Amélie Chekroun, “Manuscrits, éditions et traductions du futūḥ al-ḥabaša: état des lieux,” Annales Islamologiques 46 (2012): 305–7.

[6] Jyoti Gulati Balachandran, “Ḥājjī L- Dabīr,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam Three, ed. Kare Fleet et al. (Brill, 2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_30203. Haji al-Dabir’s full name is ʿAbdallāh Muḥammad al-Makkī al-āṣaf ī Ulugkkānī.

[7] For a longer discussion see Sana Mirza, “The Visual Resonances of a Harari Qur’ān: An 18th Century Ethiopian Manuscript and Its Indian Ocean Connections,” Afriques 8 (2017): [Online], https://doi.org/10.4000/ afriques.2052 and Sana Mirza, “Developing the Harari Mushaf: The Indian Ocean Milieu of Ethiopian Scribes,” in Muslim Cultures of the Indian Ocean: Diversity and Pluralism, Past and Present, ed. Stephane Pradines and Farouk Topan (Edinburgh University Press in association with The Aga Khan University, 2023), 28–33.

[8] Tim Stanley, “A Qur’an Once Zanzibar: Connections between India, Arabia, and the Swahili Coast,” in The Decorated Word: Qur’ans of the 17th to 19th Centuries, ed. Manijeh Bayani, Anna Contadini, and Tim Stanley (Nour Foundation, 1999), 28.

[9] Anne Regourd, “Introduction to the Codicology of the Collection,” in A Handlist of the Manuscripts in the Institute of Ethiopian Studies. Volume Two: The Arabic Materials of the Ethiopian Islamic Tradition, ed. Alessandro Gori (Pickwick Publications, 2014), liii, lvii.

[10] Angelika Neuwirth, “Al- Shāṭibī,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, ed. C.E. Bosworth et al. (Brill, 1997), 9:365–66.

[11] Frederick, Readings of the Qur’an” in Encylopaedia of the Qur’an, ed. Jane D. McAuliffe (Brill 2004), 4: 353-363.

[12] This manuscript within the Sherif Harar Municipal Museum is available online via the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/527288.

[13] J. Spencer Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia (Routledge, 2013), 242–46; Hussein Ahmed, Islam in Nineteenth-Century Wallo, Ethiopia: Revival, Reform, and Reaction (Brill, 2001), 58–59, 65. Mohammed Hassen, The Oromo of Ethiopia: A History 1570-1860 (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 154-161. Hassen mentions the role of Harari scholars who set up Qur’an schools within Harar and neighboring areas as a major factor in the Islamization of the region.

[14] While this feature fades in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century and is not found in this manuscript, within Harari naskh there is also an increased use of the kāf muʿarran (when the small s-like kāf is added to the top of the letter). Sarah Fani discusses this unique feature in greater depth in “Scribal Practices in Arabic Manuscripts from Ethiopia: The ʿAjamization of Scribal Practices in Fuṣḥā and ʿAjamī Manuscripts from Harar,” Islamic Africa 8 (2017): 144–70.

[15] Bihari calligraphic scripts were often reserved for religious texts and use of the script declines by the sixteenth century, but several later examples are known; see Eloïse Brac de la Perrière, “Manuscripts in Bihari Calligraphy: Preliminary Remarks on a Little-Known Corpus,” Muqarnas 33 (2016): 63–90.

[16] For a longer discussion of these features, see Sana Mirza, “Developing the Harari Mushaf: The Indian Ocean Milieu of Ethiopian Scribes,” in Muslim Cultures of the Indian Ocean: Diversity and Pluralism, Past and Present, ed. Stephane Pradines and Farouk Topan (Edinburgh University Press in association with The Aga Khan University, 2023), 28–33. For another example of the integration of bihari-esque scripts into local repertoires, see J.J. Witkam, “Qur’ān Fragments from Ḍawrān (Yemen),” Manuscripts of the Middle East 4 (1989): 155–74.

[17] Ahmed Zekaria, “Some Notes on the Account-Book of Amīr ʿAbd al-Shakūr b.Yūsuf (1783-1794) of Harar,” Sudanic Africa 8, no. 1997 (1998): 18; and Michel Tuschscherer, “Coffee In the Red Sea Area from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century,” in The Global Coffee Economy in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, 1500–1989, ed. William Gervase Clarence-Smith and Steven Topik (Cambridge University Press, 2003), 55–58.

[18] Karin Scheper refers to these types of bindings as wrappers. Typically they surround unsewn textblocks or loose-leaf manuscripts, but here the text block has been sewn; see Karin Scheper, The Technique of Islamic Bookbinding: Methods, Materials and Regional Varieties (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 380

[19] I would like to thank Yasmeen Khan for her analysis of the binding and codicological features of the manuscript.

[20] Anne Regourd, “Introduction to the Codicology of the Collection,” in A Handlist of the Manuscripts in the Institute of Ethiopian Studies. Volume Two: The Arabic Materials of the Ethiopian Islamic Tradition, ed. Alessandro Gori (Pickwick Publications, 2014), lxxvi, lxxx.

[21] In addition to Regourd’s work above, Richard Pankhurst notes some of the motifs found on the Harari bindings; see Richard Pankhurst, “The Manuscript Bindings of Harar: A Preliminary Examination,” Azania: Journal of the British Institute in Eastern Africa 22 (1987): 47–54.

[22] Richard Francis Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa, ed. Gordon Waterfield (Tylston and Edwards, 1894), II:40; Mohammed Moktar, “Notes Le Pays de Harrar,” Société Khédiviale de Géographie Du Caire 3 (1876): 374. Burton describes the bindings as having no equal in terms of beauty “save Persia,” whereas Moktar is less enthusiastic a few decades later, describing the bindings as “strong and durable but not beautiful.”

[23] Hassen Muhammad Kawo, “Biography of Private Collections and Codicological Features of Manuscripts in Arabic Script in South-Eastern Ethiopia,” paper presented at the Working with African Manuscripts in Arabic Scripts workshop, Northwestern University, August 2017.

[24] Scholars have long focused on the richness of these networks to highlight questions of mobility and identity, as well as the transformation of materials and objects as they transverse long-distances; see, for example, Nancy Um, Shipped but Not Sold: Material Culture and the Social Protocols of Trade during Yemen’s Age of Coffee (University of Hawai’i Press, 2017); Elizabeth Lambourn, Abraham’s Luggage: A Social Life of Things in the Medieval Indian Ocean World (Cambridge University Press, 2018); and Finbarr Barry Flood and Beate Fricke, Tales Things Tell: Material Histories of Early Globalisms (Princeton University Press, 2024), 147-190.

[25] For instance, Umberto Bongianino discusses a twelfth century manuscript which once belonged to an Almohad prince and made its way to Western Arabia before Yemen by the eighteenth or nineteenth century; see Umberto Bongianino, “An Almohad Copy of the Kitāb Al-Aġānī in Sanaa,” Nouvelles Chroniques Du Manuscrit Au Yémen 16 (January 2023): 85–95.

[26] Emeri J. van Donzel, A Yemenite Embassy to Ethiopia 1647-1649: Al-Ḥayī’s Sīrat al-Ḥabash̲a (Franz Steiner Verl. Wiesbaden, 1986), 171; Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (r.1658-1707) also received a request to send a Qur’an manuscript to the Solomonic court of Ethiopia; see E. van Donzel, Foreign Relations of Ethiopia, 1642-1700: Documents Relating to the Journeys of Khodja Murad (Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut, 1979), 12; and Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa, 1:165.

[27] I would like to thank Hassen Muhammad Kawo for bringing the Qur’an in bihari script to my attention. The Ottoman Qur’an was completed in 1123/1712 and is under the shelfmark of SH2006.0040. Based on stylistic analysis, the manuscript in the IES, under the shelfmark of IES 283, was likely produced in Oman or the Western Indian Ocean.

[28] Adrian E. Tschoegl, “Maria Theresa’s Thaler: A Case of International Money,” Eastern Economic Journal 27, no. 4 (Fall 2001): 445–46.

[29] Richard Pankhurst, “The Maria Theresa Dollar in Pre-War Ethiopia,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 1, no. 1 (January 1963): 8–26.

[30] Ahmed Zekaria, “Harari Coins: A Preliminary Survey” (MA thesis, Oxford University, 1989), 25.

[31] Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa, 1:16.

[32] Tschoegl, “Maria Theresa’s Thaler: A Case of International Money,” 446.

[33] Stanley, “A Qur’an Once in Zanzibar: Connections between India, Arabia, and the Swahili Coast,” 28.

[34] Fahad Ahmad Bishara, A Sea of Debt: Law and Economic Life in the Western Indian Ocean, 1780–1950 (Cambridge University Press, 2017), 29–30.

[35] Yasuyuki Kuriyama, “Yemen’s Relations with Ethiopia in the 17th Century and the Situation in the Red Sea,” ed. Anne Regourd and Nancy Um, Chroniques Du Manuscrit Au Yémen, special issue, From Mountain to Mountain: Exchange between Yemen and Ethiopia, Medieval to Modern 1 (2017–18): 57; Nancy Um, “Reflections on the Red Sea Style: Beyond the Surface of Coastal Architecture,” Northeast African Studies 12, no. 1 (2012): 244–71.

[36] Andreu Martínez, “Diu,” in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, ed. Siegbert Uhlig (Harrassowitz Verlag, 2004).

[37] André Raymond, “A Divided Sea: The Cairo Coffee Trade in the Red Sea Area during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” in Modernity and Culture, From the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, ed. Leila Fawaz and C. A. Bayly (Columbia University Press, 2002), 46–57, https://doi.org/10.7312/fawa11426.

[38] Rene Barendse, Arabian Seas, 1700-1763 (Brill, 2009), 201.

[39] Scott S. Reese, Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839-1937 (Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 67, 72.

[40] Reese, Imperial Muslims, 72.

[41] Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa, 1:15n2, 53n1.

[42] My thanks to Abdulahi Ahmed, Reference Librarian in the African and Middle East Division of the Library of Congress, for this observation.

[43] Mohamed Haji Mukhtar, Historical Dictionary of Somalia (Scarecrow Press, 2003), 47-48, 50-51, 218-19.

[44] This note is in a Qur’an in the Sherif Harar Municipal Museum; see https://islhornafr.tors.ku.dk/backend/manuscripts/840. The owner of the manuscript is listed as Shāshī ʻAyāḍ though the exact date of this note seems uncertain but must date before 1267/1851.

[45] Saaima Yacoob, Maintaining the Meaning: An Introduction to Waqf and Ibtida (Recite with Love, 2021), 69.

[46] These notes are also more common in Qur’ans using biḥārī script associated with India than the Harari Qur’ans, see Eloïse Brac de la Perrière, “Manuscripts in Bihari Calligraphy,” Muqarnas 33 (2016): 70.

[47] Alya Karame and Travis Zadeh, “The Art of Translation: An Early Persian Commentary of the Qurʾān,” Journal of Abbasid Studies 2 (2015): 142–43.

[48] Marcus Fraser, Geometry in Gold: An Illuminated Mamluk Qur’ān Section (Sam Fogg, 2005), 30–33.

[49] For more on the Sulawesi diaspora style, see Annabel Teh Gallop and Anne Regourd, “Zabīd and Manuscripts from the ‘Jawi’ Malay World,” Nouvelles Chroniques Du Manuscrit Au Yémen 18, no. 37 (2024): 101–2; and one example from South Asia, see Sabrina Alilouche et al., “Les Gloses Marginales et Le Fālnāma Du Coran de Gwalior, Témoignages Des Usages Multiples Du Coran Dans l’Inde Des Sultanats,” in Le Coran de Gwalior : Polysémie d’un Manuscrit à Peintures (Éditions de Boccard, 2016), 85–110. There is also a Mamluk example from 790-799/1388-1397, now in the National Library of Israel (Ms. Ar. 900).

[50] Annabel Teh Gallop, “The Boné Qur’an from South Sulawesi,” in Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum: Arts of the Book and Calligraphy, ed. Margaret Graves and Benoit Junod (Aga Khan Trust for Culture and Sakip Sabanci University & Museum, 2010), 171.

[51] Anne K. Bang, “Authority and Piety, Writing and Print: A Preliminary Study of the Circulation of Islamic Texts in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Zanzibar,” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 81, no. 1 (February 2011): 91; Gerhard Endress, “‘One-Volume Libraries’ and the Traditions of Learning in Medieval Arabic Islamic Culture,” in One-Volume Libraries: Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts, ed. Michael Friedrich and Cosima Schwarke (De Gruyter, 2016), 203–4.

[52] Peter Riddell, Malay Court Religion, Culture and Language: Interpreting the Qur’ān in 17th Century Aceh (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 85, 123; and A.C.S. Peacock, “Arabic Manuscripts from Buton, Southeast Sulawesi, and the Literary Activities of Sultan Muḥammad ʿAydarūs (1824–1851),” Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 10 (2019): 83.

[53] Michael Laffan and Michael R. Feener, “Sufi Scents Across the Indian Ocean: Yemeni Hagiography and the Earliest History of Southeast Asian Islam,” Archipel 70 (2005): 202.

[54] Gallop and Regourd, “Zabīd and Manuscripts,” 124. Furthermore, Gallop has noted the production of manuscripts in the distinctive Acehnese and Patani styles by Southeast Asian artisans operating in the Hijaz in the nineteenth century. Annabel Teh Gallop, “An Acehnese style of Manuscript Illumination,” Archipel 68 (2004), 210.

Cite this article as: Sana Mirza, “From Harar to Diu: Circulation and Reception of a Qur’anic Manuscript across the Indian Ocean,” Journal18, Issue 19 Africa (Spring 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7779.

Licence: CC BY-NCJournal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.