This dialogue brings into conversation two recent volumes on landscape. While they take different approaches, both Stephanie O’Rourke’s Picturing Landscape in an Age of Extraction (University of Chicago Press, 2025) and Kelly Presutti’s Land into Landscape (Yale University Press, 2024) foreground the potential for landscape to reveal new facets of our historical and present relationship to the environment. O’Rourke’s book explores what she calls the “pictorial protocols” of extraction—that is, how representing a landscape in a given way enabled it to be conceptualized and treated according to the logic of resource extraction in the late eighteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. Alongside this, it considers how such representations structured emerging ideas about race, climate, and waste. Presutti focuses on the making of an ideal French landscape and the real environments that needed to be transformed in order to suit that ideal. Considering work produced in a wide range of media over the course of a century, she makes an argument for landscape as a collective, intermedial process of negotiation and contestation between state power, local inhabitants, and the environment. In conversation, Presutti and O’Rourke comment on the current state of landscape studies, working with intermedial archives, and how our contemporary moment remains shaped by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century ideas about nature.

Kelly Presutti: To start, Stephanie, how exciting to have this conversation. I wanted to point out how rare a book like yours is in our discipline, one that spans diverse national contexts in pursuit of an epoch-defining idea. Extraction is such a trendy topic today. But you have given us a robust historical archive of its emergence, and of the role art played in reckoning with the consequences of a shift within Europe to an extractive, or what you sometimes call “carbonizing” economy—though, as you show, the implications of extraction go well beyond fossil fuels.

How did this archive come together for you? Did you begin with a definition of extraction and then find artworks that seemed to respond to it, or did you find commonalities across these artists and then come to understand them as being in dialogue with extraction?

Stephanie O’Rourke: It’s such a pleasure to be in dialogue. I’ll touch briefly on this question of the multinational approach because it places particular demands on the mechanics of research across Britain, France, and Germany, as well as European colonial networks in North America, North Africa, South Asia, and the Pacific. It can be challenging and time-intensive to grapple with not only different historical contexts but also with distinct bodies of scholarship. And, of course, trying to keep track of technical vocabulary in multiple languages. But equally, it was productive because it enabled me to analyze something that I characterize as emergent, as opposed to hegemonic.

KP: So, it was fine and maybe even productive that the phenomena you were tracking did not manifest in the same way in every context.

SOR: Exactly. In purely practical terms, your archive can be more forgiving. It can be lumpy. Working across national contexts also sheds light on how developments unfolded within centralized, state-administered systems in comparison with a more distributed, mercantile context. To come to the real thrust of your question, though, I did not set out to write a book on extraction. For the first three years, I understood myself to be writing a book about how landscape painting attempted to reconcile divergent ideas about human history, on the one hand, and natural history on the other. It began as a study of how landscape served as a kind of laboratory for artists to make sense of the deep time of geology, for example, or what Julia Nordblad calls the long-termism of the forest.[1] Along the way, books by Andreas Malm and On Barak were redirecting my attention to the social and economic formations at play in early nineteenth-century physical environments as coal was becoming a dominant energy source.[2] Separately, I encountered work by literary scholars like Elizabeth Miller and Nathan Hensley who were interrogating what they characterize as the forms of extraction in nineteenth-century novels and poetry.[3] This became a transformative prompt for me to return to my archive and pose a different question: what were the pictorial forms of extraction? How did pictures enact its logic?

I agree with you that the term “extraction” has become pervasive. In the introduction of my book, I set out a pretty strict definition of extraction because we risk losing its critical function and its efficacy in characterizing historical phenomena if we’re not precise about it. I argue that it is large-scale, coordinated, self-accelerating efforts to quantify, optimize, separate, circulate, and monetize the physical environment across global networks. One of the peer reviewers commented that “separability” seems key, and I agree. Speaking of how we manage terminology, another term that is quite dominant in the field is “ecology,” which I notice was not employed in your book. Is “ecology” a term you find useful?

KP: I took the hard line that the term “ecology” didn’t exist for much of the period that I was writing about, and I was trying to find more historically specific ways of discussing humans’ relationship to their environment. I also wanted to acknowledge that a lot of work has already been done defining the rise of ecologically oriented art in the nineteenth century, including of course Greg Thomas’s now classic Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France, but also more recently Maura Coughlin and Emily Gephart’s anthology on Ecocriticism and the Anthropocene. But I thought something else was happening in the landscapes I was studying.[4]

That said, I didn’t have a clear keyword, like extraction, in the way that you did, and so when I was forming the corpus of work I wanted to look at in the book there was a lot of intuition in grouping things together that I felt were all performing a similar function. What you just said about emergent versus hegemonic phenomena is actually quite helpful now to think back on. What was emerging was both an idea of the French landscape and a faith in the role representation could play in formulating that idea.

We both have found landscape to be a particularly powerful genre in times of changing relationships to the environment. I’d like to hear more about how you understand landscape to function. Early in the introduction, you note that the book will analyze the work that landscapes do.[5] I empathize with these italics, as I similarly struggled to communicate the critical potential of a genre often dismissed as a passive representation of the natural world. Can you say more about how landscapes work?

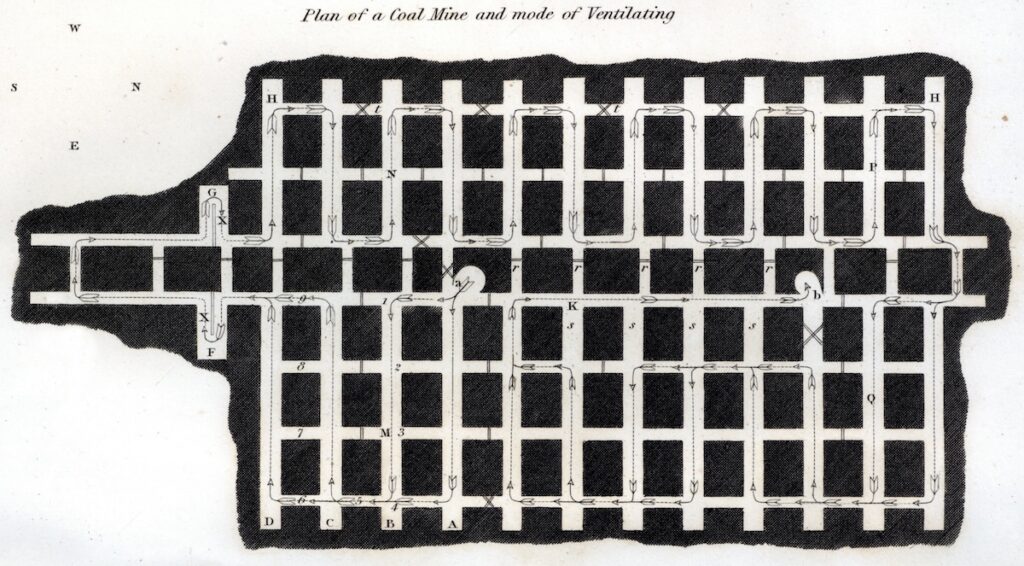

SOR: I benefited a great deal from Zoom conversations that you and I had during the pandemic lockdowns. At the time, I think you and I were both closing in on an understanding of landscape that is dynamic and mutable. As for what it is that landscapes do, the answer depends on whether you’re referring to landscape as a pictorial genre, or landscape as a larger category that can designate forms of pictorial representation such as technical diagrams, but that can also refer to physical environments, that can take into account social formations, and so on. In the case of eighteenth-century British mining diagrams, you can see novel strategies for representing space that quite literally guided the placement of new mine shafts. And those diagrammatic techniques would be employed in colonial spaces, too, which enables you to approach landscape as something that binds together distant spaces and communities. We have this art historical narrative that landscapes increasingly became about specific places in the nineteenth century. But they also enfolded within them relationships to distant places, which can be colonial spaces but can also include other social, material, and mercantile geographies. Approaching this broader version of landscape as both of a place and ultimately dislocated from it is quite productive for me.

Approaching it more art historically in the case of landscape paintings of Algeria, for example, I was querying how representing the forests of Algeria as “raw materials” languishing in a state of neglect and available to be profited off of by private and state-sponsored endeavors would encourage a broader public to share in the belief that colonial expansion in North Africa would enrich France through the appropriation of natural resources. So, in that case, I had to think more laterally and indirectly about the “work” of landscape, although what constituted a landscape was more narrowly defined.

You write that landscape is a “collective, intermedial process that unfolded over an extended period,” and I particularly admired how much your book attended to those aspects of landscape throughout.[6] Can you talk more about what it means to think about landscape, not as a genre or an entity, but as a process? How did you come to think of it that way, and what alternative possibilities do you think it opens up?

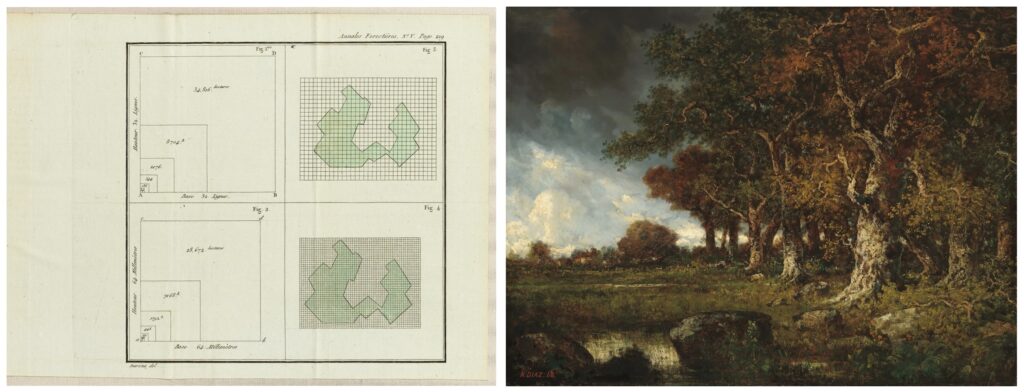

KP: I’ve remained very influenced by WJT Mitchell’s iconic statement “landscape is a verb” in the Landscape and Power anthology.[7] Then talking about landscape intermedially was really productive in circumventing questions about what environments “really looked like.” There’s still this temptation to compare the picture to the place, but instead, when I was thinking about how a painting of a forest relates to a diagram of a forest, there’s this other space that opens up, a mediated space where ideas about environments are formulated, negotiated, and redefined. It became, to some degree, about pictures talking to pictures in ways that had significant impacts, like certain forest supervisors boasting that they no longer needed to go to the woods, they could do everything from their office thanks to images. These images created what I end up calling in one chapter a “floating territory” that’s hovering over the actual landscape and becomes operative.[8]

Right: Fig. 3. Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, The Edge of the Forest at Les Monts-Girard, Fontainebleau, 1868. Oil on canvas, 38 1/2 × 49 7/16 in. (97.8 × 125.5 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Chester Dale Fund.

This continues to condition how we relate to the environment today. So much environmental research happens via image, so it was important for me to look back at how the imagification of environments occurred in this moment.

SOR: One of your most interesting moves is your focus on what you call environments that were difficult to picture, and that therefore called into question the whole enterprise of picturing landscape. Are there particular characteristics that make something difficult to picture, and what does it mean to tell a visual history of that kind of phenomenon? Equally, what would be a landscape that isn’t difficult to picture?

KP: Tackling subjects that were difficult to picture was part of what drew me to the works I studied. The reasons for that difficulty vary. They included formal factors like scale, density, and a lack of definition, but they also included social and political factors, like ownership, use rights, and the perceived value of the land. What was surprising to me, and what I think made the book work, was that the social and political factors were often tied to formal concerns, meaning visual representation was uniquely suited to address social and political difficulties. For example, it was hard to know the boundaries of the forest, as the density of trees often defied mapping efforts, but representation that made a forest visible as an object could be both practically and conceptually useful.

I love this second part of your question about a landscape that’s not difficult to picture. I think a landscape I took for granted was the cultivated field. For me, it’s an environment that seems almost engineered for picturing, it’s designed to be immediately legible, countable, quantifiable, as you might say, extractable, but also became such an icon of France through images like Monet’s haystack. This is not to say the cultivated field is an uncontested landscape, especially when we think about the colonial context where the imposition of monocultural agriculture was particularly harmful, as in Algeria.

SOR: What was it like in practical terms as a researcher who’s compiling an archive to have your object of study be either unpicturable or something that will always evade the systems of registration brought to bear upon it?

KP: One thing that was really helpful for me was that I started by gathering a lot of representations of specific places. I began with something that Greg Thomas defined a long time ago as the “topographical aesthetic,” a growing desire to no longer show classical, idealized landscapes, but instead to depict real places. And then I gathered a lot of archival information about the fraught discussions that were happening around the management of those places.[9] What I eventually noticed was that both visual representation and the debates on land use and management coalesced around particular kinds of landscapes, which became the chapters of the book: mountains, coasts, forests, and wetlands.

Once I saw that those were all places that had shared pictorial and political difficulties, then I could more effectively recognize things that fit that paradigm. But like you, it was years into the process before I got to that point.

SOR: Which landscape typology was the most difficult for you to write about or pin down?

KP: “Coasts” was the most challenging because France has a complicated relationship to its maritime identity. In that chapter, I charted a tension between the desire to expand France outward and a concern with continental security, especially given the decline of the navy with the fall of Napoleon. By the mid-nineteenth century, the navy was seen as underfunded, and not coincidentally, marine painting was also seen as a dying genre. So coasts were a landscape that didn’t fully resolve over the time period that I consider in the first book, and in the work I’m doing now I’m thinking more about how visual representation was negotiating that complex position between inward looking and outward expansion, between perceived failure and the reality of France’s maritime strength.

In some instances, like John Martin, artists were actively involved in designing solutions to problems posed by extraction. But in other instances, the relationship between artist and environmental impact is one of simultaneity. In your discussion of French forestry, you note that “at the very moment” a new Forest Code is put in place, Paul Huet was painting forests, and “at this very moment” that Eugène Fromentin is depicting an Algerian cork oak, the French were engaged in industrial-scale harvesting of Algerian forests.[10] How did you treat the issue of artists’ intention or agency with regard to environmental change?

SOR: You have to be willing to approach it differently across your protagonists. In the case of Caspar David Friedrich, for example, I was surprised by the extent to which mining and timber management were being actively discussed and studied by those around him. We know he explored areas that were undergoing major experiments in modern scientific forest management. However, there really was not a comparable discourse in Britain for romantic artists. That’s not to say that important British romantic writers and artists had no contact with such practices because they absolutely did, but discussion of it was not as central to elite forms of sociability and intellectual exchange when compared to Dresden.

In the case of Paul Huet and Eugène Fromentin, I situate them within a lineage that comes from the eighteenth century rather than the more immediate context of the Forest Code of 1827. Either way I believe, and I suspect we agree on this point, that figures like them were ultimately in the business of converting French woodlands into commodities. So we can see them adopting or sharing in at least some of the logic of extraction without needing to assert a strictly causal relationship.

Speaking of which, you write that the forest didn’t always exist as a landscape but was made into a landscape in and through nineteenth-century representations of it. I was very struck by the difficulty you identified in demarcating a clear boundary between a forest and its surroundings. You also write in that chapter about Théodore Rousseau’s use of bitumen. How does materiality factor into your analysis?

KP: That’s really great. I’ll start with the boundaries question, because it is a huge issue across all of the chapters, and it has a lot to do with this shift in France to a private property model in which territory has to be mapped and bounded and parceled so that it can be redistributed. It has to do also with the very shape of France. The chapter about mountains looks at how as artists and geologists paid more attention to the realities of mountains, it became increasingly apparent that the Pyrenees don’t always function as an effective boundary between France and Spain, so eventually a line has to be drawn on a map.

These boundary issues became formal problems that, as I alluded to earlier, visual representation can help to solve or seem to solve. And yet, that said, the stuff contained within the bounded area doesn’t necessarily behave. That’s what I love about the bitumen example. Rousseau, who, as you say, helps contribute to defining a forest as a separable, sellable thing—I think I learned from you that he had worked counting trees in his youth—also wants to acknowledge the density and intractability of what he’s experiencing in the woods. Bitumen, a tarry, asphalt-like substance, becomes a way for him to get at the rich, organic coloring of the woods. But bitumen never fully dries, and so it’s constantly agitating beneath the surface of his painting and upsetting any perceived order. There’s the attempt to create a bounded entity, and then there’s the uncontainable qualities of the artworks, and that tension was really productive for me as I was thinking about these landscapes.

Ultimately, your book ends up being about humans as much as the environment; you reference a nineteenth-century author who observes that, in your summary, “what is done to the natural world under the sign of extraction is always also done to the human.”[11] I’m struck by the awareness of the harms of extraction right from the start, and intrigued by the structures—like race—that allowed those responsible for extraction to believe themselves exempt from those harms. Images were a way to circumscribe and manage the hazards of extraction, from John Martin’s attempts to contain subterranean flows to Pacific explorers’ racialized depictions of Indigenous bodies. And yet you, and I too, hold out hope for images, for what they, as you say in conclusion, “might yet do.”[12] Can you point to some more hopeful examples, from this book or from work you’d still like to do?

SOR: What was distinct about this book compared to my first book is that my artworks are not heroic actors. There’s an incredible temptation to identify our case studies as subverting problematic paradigms or expressing opposition to problematic political formations. And here, I challenged myself to write about and become invested in artworks that might be understood to enact or even embrace the pictorial strategies of an economic system that is violent and depletionary.

So rather than point to an example of an artwork that resists extraction, I’d prefer to say a few words about how this historical archive can help us understand our present reality. In his book on early nineteenth-century American energy infrastructure, Christopher Jones writes about “landscapes of intensification.”[13] This is essentially a self-accelerating positive feedback loop that occurs in mineral-based energy regimes like the one that still dominates today.

It’s incredibly capital-intensive to build the infrastructure to transport mineral-based energy (such as a canal system to transport coal), so it was existential for these endeavors to create market demand for the energy, market demand that didn’t really previously exist. Growth in consumption drove infrastructural expansion, which boosted supplies and lowered costs, and so on. Canals are one example of a physical environment that accelerated and entrenched (or, “intensified”) an energy regime as well as the market structures which accompanied it. Jones identifies this as a “landscape” because it’s a real physical environment whose contours and properties play a determinative role, but it’s also a way of conceptualizing an environment. This very effectively captures part of what is happening with AI today with the desperate drive to create consumer demand being led by major corporate entities, and Jones reminds us that landscape plays an active role. A question I’d like to consider is, how could artistic representations of landscape effect “intensification?” What are its pictorial forms? Answering that might better equip us to identify countervailing pictorial strategies.

Where do you see the study of landscape at the moment?

KP: Yes, as you were just saying, there’s a huge revival of interest in landscape right now. I think for a while the genre was considered worn out, maybe after the boon of Marxist studies of the British landscape in the 1980s. But I find there’s a lot of fresh energy in the field with regard to our present environmental crises, which is driving renewed attention to the genre. And I’m mostly just looking forward to being in conversation with more scholars like you who are advancing what landscape can be and do.

Stephanie O’Rourke is a Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of St Andrews, Scotland

Kelly Presutti is Assistant Professor of History of Art at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY

[1] Julia Nordblad, “Time for Politics: How a Conceptual History of Forests Can Help Us Politicize the Long Term,” European Journal of Social Theory 20, no. 1 (2017): 164-82.

[2] Andreas Malm, Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming (Verso, 2016); On Barak, Powering Empire: How Coal Made the Middle East and Sparked Global Carbonization (University of California Press, 2020).

[3] Elizabeth Carolyn Miller, Extraction Ecologies and the Literature of the Long Exhaustion (Princeton University Press, 2021); Nathan K. Hensley, Action Without Hope: Victorian Literature after Climate Collapse (University of Chicago Press, 2025); Nathan K. Hensley and Philip Steer, eds., Ecological Form: System and Aesthetics in the Age of Empire (Fordham University Press, 2018).

[4] Greg M. Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau (Princeton University Press, 2000); Maura Coughlin and Emily Gephart, eds., Ecocriticism and the Anthropocene in Nineteenth-Century Art and Visual Culture (Routledge, 2019).

[5] Stephanie O’Rourke, Picturing Landscape in an Age of Extraction: Europe and Its Colonial Networks 1780-1850 (University of Chicago Press, 2025), 5.

[6] Kelly Presutti, Land into Landscape: Art, Environment, and the Making of Modern France (Yale University Press, 2024), 7.

[7] W.J.T. Mitchell, ed., Landscape and Power (University of Chicago Press, 1994).

[8] Presutti, Land into Landscape, 56.

[9] Greg M. Thomas, “The Topographical Aesthetic in French Tourism and Landscape,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 100-120.

[10] O’Rourke, Picturing Landscape in an Age of Extraction, 29-61.

[11] O’Rourke, Picturing Landscape in an Age of Extraction, 175.

[12] O’Rourke, Picturing Landscape in an Age of Extraction, 182.

[13] Christopher Jones: Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Harvard University Press, 2014), 8.

Cite this note as: Stephanie O’Rourke and Kelly Presutti, “Art, Environment, and the Expanded Landscape: A Dialogue” Journal18 (February 2026), https://www.journal18.org/8076.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.