Christelle Lozère

During the eighteenth century, two seemingly contradictory models of sociability emerged in France and Britain. Libertinage, whose sensual and philosophical stakes were perhaps most memorably explored in the writings of the Marquis de Sade, thrived in some aristocratic circles. By contrast, Jean-François Marmontel’s “Moral Tales” of 1761 reflected a growing call among Enlightenment thinkers and artists for a return to a simpler, more virtuous life in harmony with nature. These paradoxical moral idioms did not just inform white European society, however. They were also critical to how Europeans conceptualized and contested the moral status of slave societies in the Caribbean. Numerous engravings revealed—sometimes by condemning them—the depravity and immorality of a slave society focused on maintaining a colonial economic system and warned European viewers about the consequences of interracial unions. At the same time, other prints perpetuated a serene and sugarcoated image of Creole societies in response to the emerging influence of abolitionist movements at the end of the century. These two categories of prints constitute a kind of inverted mirror, revealing two divergent European imaginaries of Caribbean slave society in conflict at the turn of the nineteenth century.

The Family, Bearer of Moral Values, Securing the Social Order

In the first half of the eighteenth century, artistic depictions of idealized virtuous, happy, and united families reflected views espoused by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and others who cautioned their readers against the corrupting influences of modern society and exhorted them to return to nature and simplicity. Maternal tenderness and a mother’s responsibility for the transmission of educational values were seen as key elements of an Enlightenment interest in a moral reform of the French social body.[1] Many artists and thinkers, including Jean Siméon Chardin, Jean Baptiste Greuze, Denis Diderot, and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, believed that art could help usher in a return to a superior moral and social order.[2] Others members of the European aristocracy—most notably Queen Marie-Antoinette of France—tapped painters such as Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun to burnish their image and their morality vis-à-vis the people.

This call to morality took on particular significance when it intersected with the contemporary interests of both enslavers and abolitionists, examples of which surface powerfully in artworks produced in both colonial contexts and metropolitan France. In Martinique, the Marquis de Choiseul-Meuse commissioned three group portraits from the painter Marius Pierre Le Masurier (1735-1801): one of an enslaved family (Fig. 1), one depicting a mixed-race family (Fig. 2), and finally a painting of Choiseul’s own family (Fig. 3).[3] The commissions exemplify a bid to show a Martinican Creole society in 1775 free of social tension, one in which moral and educational principles were transmitted to enslaved and free people of color, and one whose social order was maintained by the dominant white elites in accordance with the hierarchy of races.[4] Doing so through the pictorial and social idiom of the nuclear family served as a rebuke to eighteenth-century authors who considered it axiomatic that enslaved people could not have families. For these writers, as historian Arlette Gautier has noted, slavery was anti-family by nature.[5]

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the prospect of abolition in France’s colonies (achieved in 1848) only heightened the importance of efforts to map these familial structures and values onto enslaved people. Le Masurier’s paintings anticipate these later efforts by putting forward an idealized vision of a multi-racial colonial society characterized by hierarchical stability and its adherence to the social virtues espoused by figures like Rousseau. Each social group appears compartmentalized as a fixed category, with a background indicating its respective status: the family of enslaved people is represented on the plantation close to their modest abode; that of the free people of color occupies a more comfortable home, illuminated by sunlight streaming in through an open door; and, finally, the white family resides in a luxurious interior decorated in the latest Paris fashion. The enslaved man and the free man of color are presented as happy and united among their fellow men; the Black domestic staff, through the image of a nurse holding a baby, is integrated into the family of Choiseul, whose whiteness is reinforced by the contrasting skin tone. This triptych aims to demonstrate that intergenerational family ties and their attendant social virtues were maintained in the colonies.

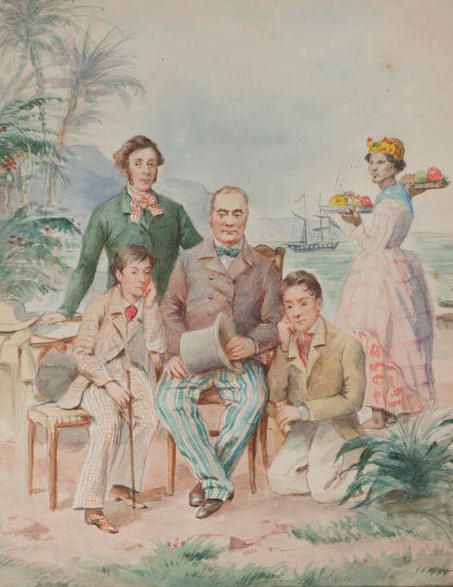

Similarly, an anonymous portrait of Joseph Roubeau in Guadeloupe with his three sons and maid, held in the Musée des Arts décoratifs et du Design in Bordeaux, portrays the father as the center of the white family (Fig. 4). While the mother is seemingly absent from the watercolor, the presence of the mixed-race maid in the background carrying trays laden with fruit raises questions about her true status within the family––is she perhaps the mother of the children? The triangular shape of her face and hairstyle discreetly rhymes with the features of the eldest son, while the red checks and her pink dress are reflected to varying degrees in the details and coloring of the clothes worn by the three boys. The blue in the scarf placed on her shoulders, meanwhile, corresponds to that of the bow tie around Joseph Roubeau’s neck. Yet such illicit extramarital resemblances are situated within a compositional framework whose structure is explicitly stratified and stable: the family’s union seems to be built around a separation of social classes, whereby the whiteness of skin determines the figures’ position in the image.

In British colonial contexts a similar dynamic can be seen. For example, the portrait painter Philip Wickstead (1763-1786), trained by Johan Zoffany, depicted the family of Henry James in 1790 at his Jamaican property in Southfield on St Ann’s Bay.[6] The painting portrays James with his wife Elizabeth (née Jones), their six children (James, John, William, Edward, Elizabeth, and Josiah), their maternal grandmother (Catherine), and their tutor. In this conversation piece, the family of the surgeon, who had been practicing in the colony since 1767, is presented as united, racially unmixed, slim, elegant, and above all educated, as attested by the prominence of a library filled with encyclopedias and a globe. Similarly, Wickstead’s Edward East and Family depicts a young settler couple, richly dressed and surrounded by their two young children posing at their mansion. The mother of the family, who bears a porcelain complexion, holds her infant against her body, affirming the strength of affective and hereditary links between white European mothers and white European children in colonial Jamaica. Across these paintings, we see artists putting forward a vision of colonial slave societies that are buttressed by the Enlightenment family unit, both as a source of moral virtue per the philosophes (and) as an agent of social and racial stability.

Perverted Bodies, Symptoms of the Evils of Slavery

The proliferation of print media in the late eighteenth century coincided with a growing appetite for pictorial satire—a kind of imagery that sought to mock and expose the moral failings of various social groups. The French revolutionary period amplified the circulation of engraved images demonizing and ridiculing the nobility, in direct contrast to the idealized portrayals found in the kind of conversation paintings discussed above. In England, modern moral subjects—grotesque stagings of aristocratic and bourgeois life epitomized by the work of William Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson, and James Gillray—testify to the popularity of satire as a pictorial mode and to a broader culture of incisive and humorous self-regard.[7] Like the French aristocracy, British colonial slave society was not spared the piquant, burlesque, and critical humor of the caricaturists, who were the journalists of their time, with a sharp and unrelenting eye. Just as caricaturists lampooned the foibles and failings of Georgian London, so too did they turn their attention to the immorality of white settlers in British colonies. Abolitionist imagery presented their bodily excesses and depravity as symptoms of the evils of slavery.

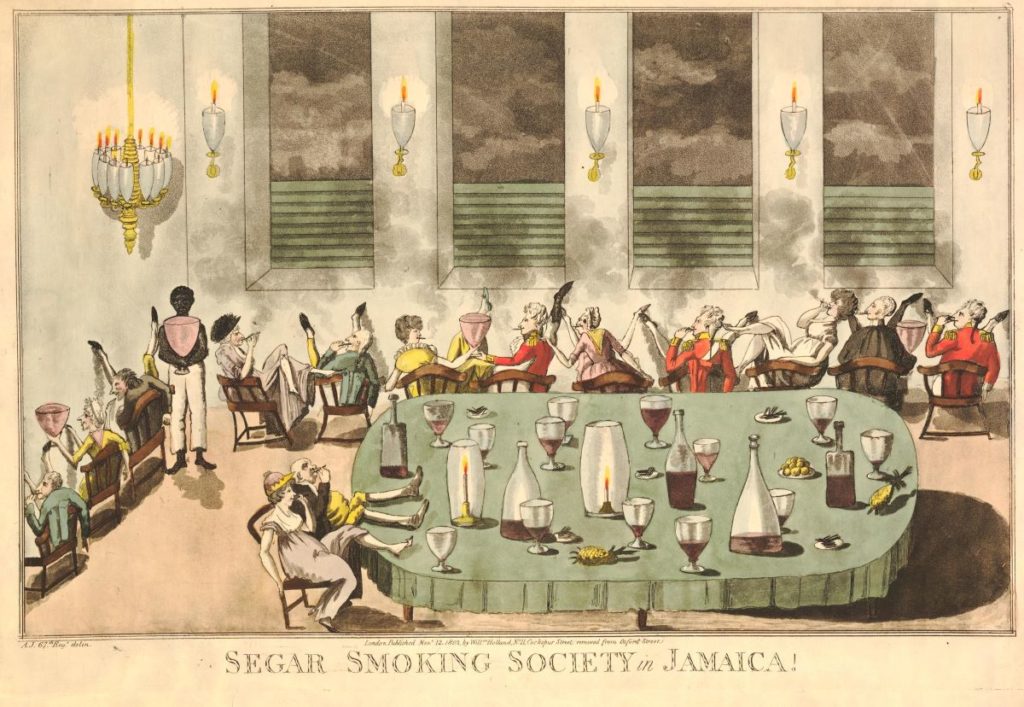

Bearing little resemblance to the sophisticated patriarchs seen in the portraits of Le Masurier and Wickstead, the European enslavers portrayed in popular satirical prints were characterized as alcoholic, lazy, and violent, and were shown keeping company with sex workers and disregarding their familial duties. In a print made at the beginning of the nineteenth century, British publisher William Holland’s subversive images also revealed a profane, carnivalesque, and depraved Jamaican colonial society. In Segar Smoking Society in Jamaica!, published by Holland in 1802, the illustrator Abraham James, then stationed as an officer in the colony, highlighted the dissolute life of the white Creole plantocracy (Fig. 5). The scene is set inside a private club where the space is dominated by a large, oversized oval table with numerous decanters of alcohol, large goblets, cigars, two pineapples, a fruit dish, and two lit candles. At the edge of the room, smokers sit nonchalantly facing large windows. The general disorder and the careless poses of the characters—soldiers, planters, a pastor, and about six women, some of whose legs are spread on the tables or against the walls—suggest unseemly libertine practices. Witnessing the debauched morals of the guests, a bare-chested and barefoot Black servant holds a gigantic empty goblet and stares downward in desolation. His blank, affective gaze prompts viewers to connect his servile social condition with the excesses of an amoral colonial slave society corrupted by vice.

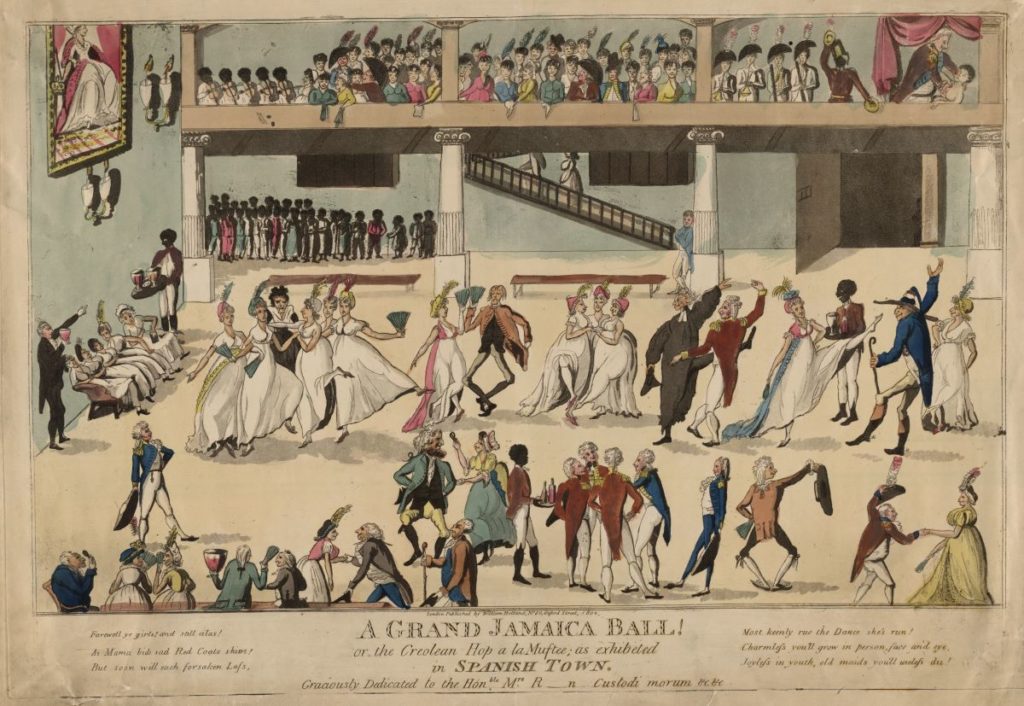

Another eighteenth-century print published in London, A Grand Jamaica Ball, contains six verses warning Creole women against a loose and idle life (Fig. 6). At a ball in Spanish Town, men and women served by Black enslaved people engage in ballroom dancing with disjointed leg movements. A group of Black children are present in the background as motionless spectators of the scene. Upstairs in a gallery, a group of satisfied onlookers observe the festivities to the sound of Black musicians playing violins. At the edge of the ball, under a red drape the color of spilled blood, a rape scene of a topless white woman undressed by a planter seems to be met with the general indifference of the crowd.

Similarly, stereotypical and sexualized representations of women of color, and particularly mixed-race women, gained popularity, indexing in eroticized postures both the fear and the fantasy of racial mixing in colonial society.[8] Such immorality was underscored in the caricature of Rachel Pringle of Barbados by Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1826), printed in 1796, depicting the mixed-race Rachel Pringle Polgreen (1753-1791) as an imposing brothel owner in Bridgetown, sitting inside her store waiting for customers (Fig. 7). The illustrator, known for his erotic woodcuts and etchings, highlights Rachel’s large bosom through a low-cut white dress, while her ample legs are spread wide, crudely exposing her to the customer’s gaze. In the background are three figures: a young Black sex worker with breasts protruding from her bodice converses with a white man in torn clothing, while a British officer discreetly watches through the window.[9]

Rowlandson’s depiction of Polgreen (née Lauder)—the first woman of color to run a brothel in Barbados—foreshadows her depiction in J. W. Oderson’s moralistic and nostalgic novel of slavery, Creoleana, or Social and Domestic Scenes and Incidents in Barbados in the Days of Yore, published in London in 1842. Telling the story of Polgreen’s abuse by her white father alongside her later tyrannical turn as a brothel owner, Oderson’s account exemplifies the paradoxes Marisa J. Fuentes has highlighted in her writing on women in the Caribbean during enslavement: even as they were dependent and subordinate to its economic and social strictures, women like Rachel also perpetuated the system by exploiting other women. [10] An article published in The Journal of The Barbados Museum and Historical Society in 1942 reads Rowlandson’s image of Rachel in both youth and maturity as a reflection of the physical ravages caused by the vices of prostitution, which were thought to deform bodies.[11] Rachel’s depictions in both Rowlandson’s caricature and Oderson’s novel explicitly link her moral depravity with her racial identity, refusing the feminine familial virtue that painters like Le Masurier strove to attach to Creole families.

In the late eighteenth century, prints and paintings supporting British abolitionist propaganda contested the harmonious vision of enslavement articulated in conversation paintings by Agostino Brunias, Le Masurier, Savart, Wickstead, and many others. These images pictured a Caribbean slave society far from Christian morality and marked by sin—libertine, grotesque, lascivious, and alcoholic—where oppressed and abused enslaved people were spectators or victims of fin-de-siècle decadence. However, with the re-establishment of slavery in 1802, powerful colonial lobbies made it more difficult for satirical prints to openly challenge the moral vision of enslavement that had been popularized by Brunias and Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur decades earlier.

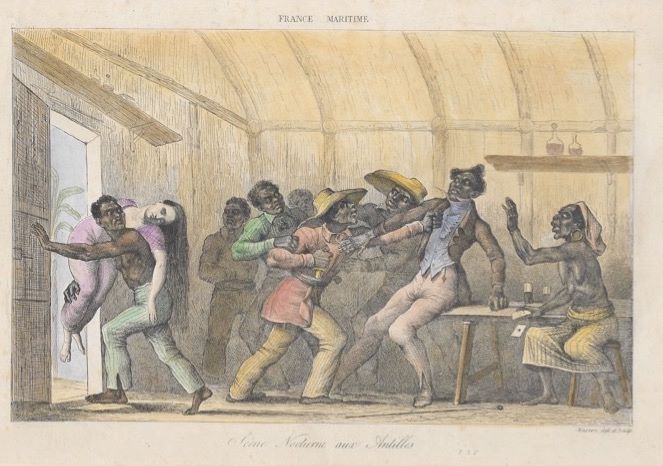

Instead, artists paradoxically turned to the moral vocabulary of British abolitionist prints to articulate the anxieties of enslavers, who feared revolts amplified by the recent abolition in the British colonies.[12] In the French West Indies, for example, artists mobilized the perceived dangers faced by white women to support anti-abolitionist iconographic propaganda. In Night Scene in the West Indies (1835), a print by an artist named Masson, the fainted white heroine Virginie is rescued from the clutches of a group of Black and mixed-race men fighting in a squalid gambling den (Fig. 8). Rather than portray Black and mixed-race people as victims of human barbarity, the print suggests they are immoral, coarse, dangerous, savage, uneducated, violent, envious, and vindictive beings. In a Europe fond of gothic novels and their casts of menacing characters, nocturnal settings such as the one found in Night Scene in the West Indies were seen to be especially threatening to white women. The interior of the cabaret, as a place of debauchery, gambling, and drinking, appears conducive to the moral failings the print attributes to its Black characters.

The elite pictorial vocabulary of familial morality, on the one hand, and the printed caricatures that satirized moral failings, on the other, were instrumental in propagating competing visions of European enslavement. Within shifting historical and political contexts of the long eighteenth century, artists moved back and forth between these alternative modes of picturing. In doing so, they played a vital role in the contingent construction of race in the Caribbean and metropolitan France.

Christelle Lozère is maître de conferences in Art History at the Université des Antilles, Schœlcher

[1] Isabelle Brouard-Arends, “Entre nature et histoire. Dire la maternité au siècle des Lumières,” in Olga B. Cragg and Rosena Davison, eds., Sexualité, mariage et famille au XVIIIe siècle (Laval, Presses de l’Université Laval, 1998), 233-250.

[2] Greuze et Diderot: vie familiale et éducation dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle (Clermont-Ferrand: Musée Bargoin, 1984).

[3] Maximilien Claude Joseph de Choiseul-Meuse (1736-1816) took part in the Seven Years’ War and was promoted to general assistant major in Martinique in 1766, then to second-in-command of the island, before becoming a brigadier of the king’s armies.

[4] Anne Lafont, L’art et la race: L’Africain (tout) contre l’œil des Lumières (Paris: Les Presses du réel, 2019).

[5] Arlette Gautier, “Les familles esclaves aux Antilles françaises, 1635-1848,” Population 55, 6 (2000): 975-1001.

[6] Accompanied by the landscape artist Georges Robertson, Philipp Wickstead followed the sugar planter William Beckford of Somerley from Rome to Jamaica. He stayed there from 1784 to 1786. He painted several portraits of the local elite and their families and exhibited his work at the Jamaican Society of Artists. See Frank Cundall, “Philip Wickstead of Jamaica,” Connoisseur 94 (1934): 174-175.

[7] Jessica Fripp, Amandine Gorse, Nathalie Manceau, and Nina Struckmeyer, eds., Artistes, savants et amateurs: art et sociabilité au XVIIIe siècle (1715-1815), Actes du colloque international organisé du 23 au 25 juin 2011 à l’INHA (Paris: Mare & Martin, 2016), 139-154.

[8] Kevin P. Murphy and Jennifer M. Spear, eds., Historicising Gender and Sexuality (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

[9] Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Woman, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 52.

[10] Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives.

[11] “Rachel Pringle of Barbados,” Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society 9, 3 (1942): 112-119.

[12] Scène nocturne illustrates an episode of a short story published in 1835 by Louis de Maynard de Queilhe (1811-1837) in volume III of La France maritime.

Cite this article as: Christelle Lozère, “Order and Disorder: The Iconography of Morality and Colonial Enslavement”, Journal18, Issue 13 Race (Spring 2022), https://www.journal18.org/6322.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.