Editor’s Note: Published in three installments, this intervention by L’nu interdisciplinary artist, poet, and scholar Michelle Sylliboy offers an Indigenous perspective on the colonial archive. Sylliboy responds to the dehumanizing accounts of her ancestors in Nouvelle Relation de la Gaspésie (Paris, 1691) and reclaims the komqwejwi’kasikl language from its author, French missionary Chrestien Le Clercq, who culturally appropriated its writing system. Using autobiographical creative inquiry and Nm’ultes theory, Sylliboy addresses the ongoing impact of settler colonialism on her people, the L’nuk. As a survivor of intergenerational trauma, she tells the intersecting stories of healing and reconnecting with the worldview of her ancestors, who have been caretakers of a land that stretches from the Gaspé peninsula to Newfoundland since immemorial times.

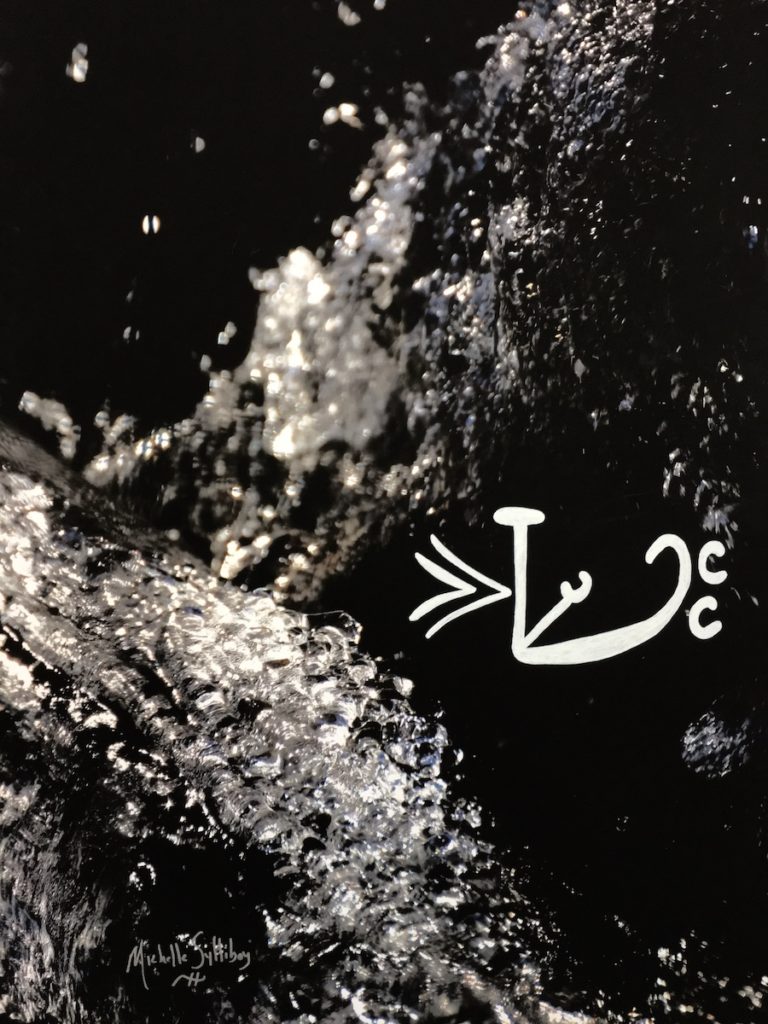

Michelle Sylliboy, Jiksituinen / Listen to Us / Écoute-nous, 2019. Wasoqitestaqn / Digital photography / Photographie numérique, 86.4 x 58.4 cm. © Michelle Sylliboy.

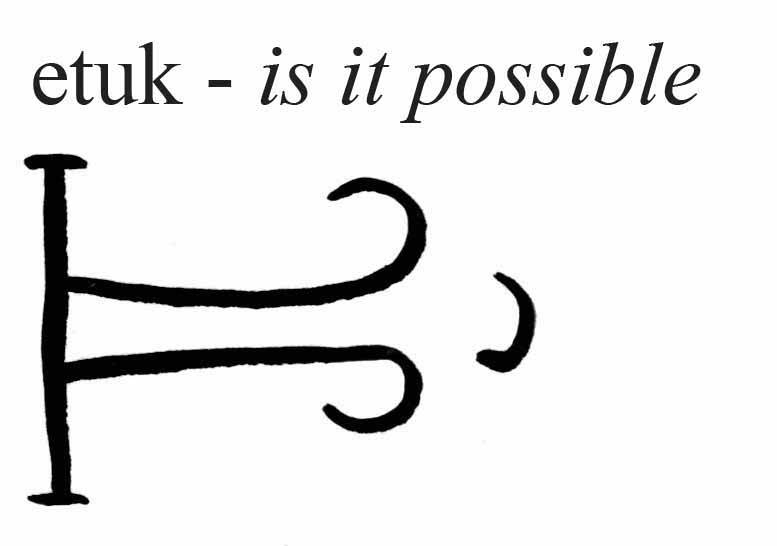

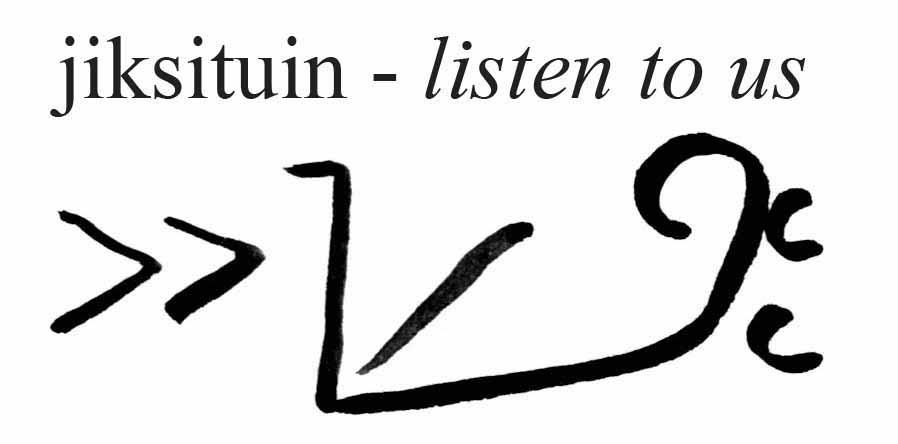

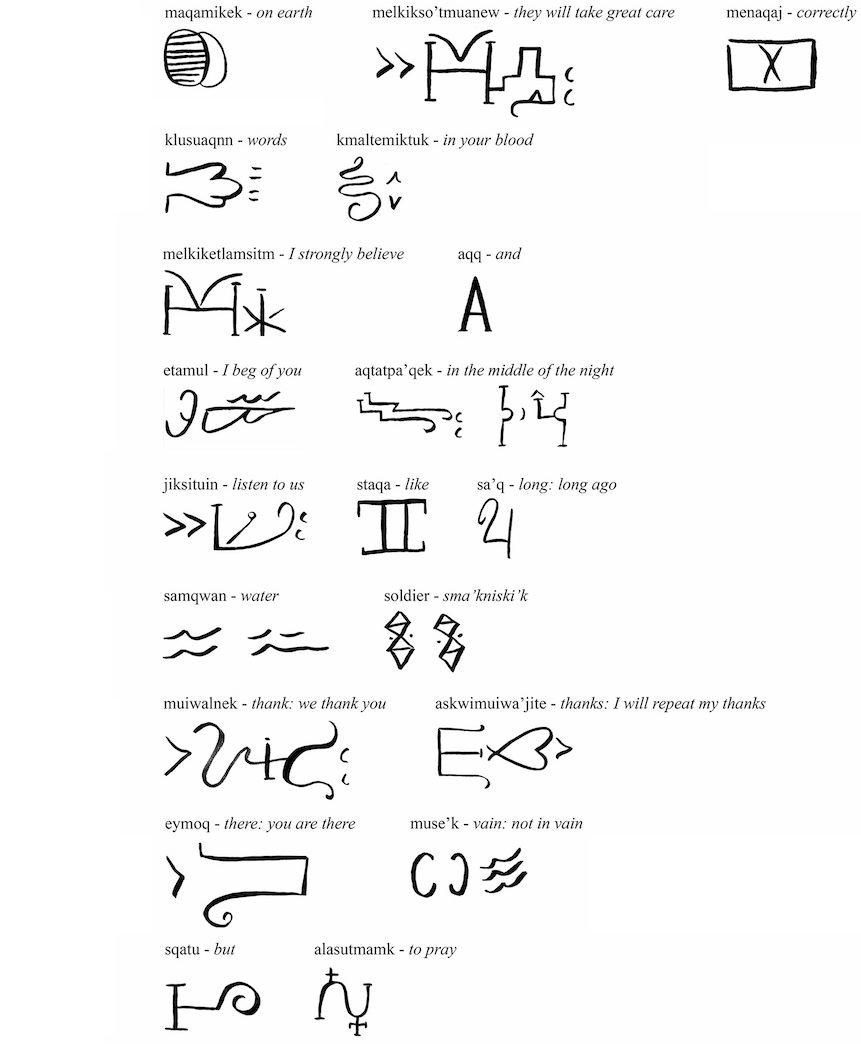

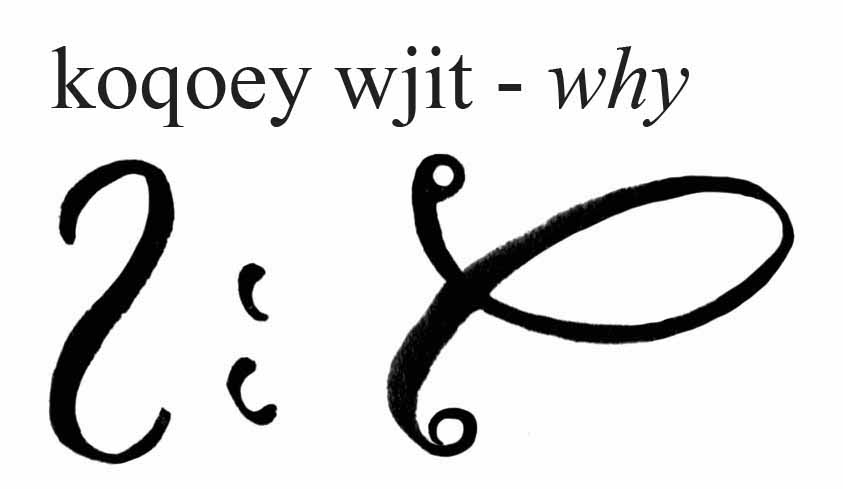

In the L’nuk (Mi’kmaw) language, there is no word for “goodbye,” in the same way there is no end to learning.[1] Nm’ultes, which infuses the writing process of this text, is the by-product of this worldview. It represents an ongoing dialogue between two or more people and is a meeting of the minds in the future, an exchange of stories that will continue either in person or in the spirit world. Nm’ultes takes place in multiple ontic dimensions. I know this about the L’nuk language, though: it does not always have a definitive perspective or meaning. It is a beacon to the L’nuk culture of a multilayered internal dialogue with the ancestors. My elders call this language komqwejwi’kasikl, and it is the unofficial written language of my people. The late L’nu scholar Murdena Marshall wrote: “The ornate symbols came to be called komqwejwi’kasikl, literally “sucker fish writings”—the sucker fish (komqwej) being a riverine bottom feeder that, in its quest for food, leaves a muddy filigree.”[2] The best way to describe it is to say that we often speak between worlds, literally and metaphorically. A spiritual description and connection to the outer realm is part of L’nuk ontology and how my Nm’ultes paradigm unfolded using the komqwejwi’kasikl language as the catalyst. For me, Nm’ultes expresses a better understanding of the collective consciousness that has motivated me to keep learning how to decolonize and reclaim my Indigenous voice.

A French missionary stole our historical narrative with outlandish claims about our written language.[3] However, this claim has been contradicted by my elders, such as our esteemed L’nu historian, the late Ms. Lillian B. Marshall, who asked me, in our last conversation before she died, to make sure to tell “them” that we’ve always had our language.[4] Her statement is an infinite timeline that predates the missionary’s account. As an interdisciplinary L’nu artist and poet, a key theoretical question to arise, and one that I address in this text, is: How does Nm’ultes research and methodology inform my work as an intergenerational child of an Indian residential school survivor?

Reclaiming the komqwejwi’kasikl language is L’nuk epistemology in action. Komqwejwi’kasikl is a verb-oriented language requiring dramatic expression. Its writing system enhanced my narrative—a broken story reshaped by distance, time, and the desire for healing. Nm’ultes also interweaves my story to the homeland of komqwejwi’kasikl. Using creative-inquiry analysis, I decolonize my discourse and allow it to become a spiritual bibliography that carries my ancestors’ worldview. My poetry embeds the komqwejwi’kasikl thought process and repatriates it as a living language.[5]

A living bibliography

would pause for a moment,

repeating sounds of a main expression

an artistic description of noble dreams

dancing before my eyes

not by a sledgehammer of words forcing

uninvited thoughts, towards

crisp clear antidotes who

reposition themselves on purpose

as a result, transported imagery

of an ancestral throat

howls a deep language of sound

administered from the belly of my inner core

breath work solidifying sounds of

vibrating pencil marks through an inkling

whispering

sing me a wish making noise

we are listening little one

we are always listening

envelope is sealed with a tremor of hope,

along the ridges of immortality of weighted gifted tongues.

uncontrollable energy arises

blood moving throughout the body

responding only to an unexpected spiritual visit

disguised as a muse proximity to orality

a fresh moment of truth occurs

when you turn everything of

in your apartment a bird in the distance

inspires your next thought process

L’nu Inquiry as a Lived Experience

Setting the stage requires me to give my ancestors permission to be blunt, even in stressful situations, like one that occurred on a cold November day that changed the course of my life. It had been a stressful day at work, and I waited several minutes for a family to pull out of a parking spot, which they were in no hurry to do. Completely annoyed, I slammed my foot on the accelerator and went down another street. What happened next shifted my perspective on my little world: I had an encounter with a blossoming cherry tree. My frustration about a missed parking spot was no longer a priority. Instead, my mind was inspired by a tree unexpectedly full of cherry blossoms in early winter. This apparition was a quintessential moment of awe and fulfillment that allowed me to trace each step, from uncertainty to certainty, on an unwritten map towards healing. Unbeknownst to the dawdling family in the car, not pulling out of the parking spot more quickly had resulted, for me, in an encounter that triggered a wave of previously buried emotions connected to the intergenerational trauma of residential schools.

I am the child of a mother who was a student in, and a victim of, the Canadian residential school system, a legislated government attempt, from the late 1800s to the early 1990s, to colonize Indigenous children by removing them from their homes and families. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that Canada implemented in 2007 emphasized that the goal of the residential school policy had been, all along, “not to educate them, but primarily to break their links to their culture and identity.”[6]

Parents were forced to send their children far from home to schools whose teaching environments bore no resemblance to the L’nuk or First Nations cultural ways of life.

From birth to death, we crave existential moments of connection with Mother Nature when signs appear, redirecting us to an unspoken conversation with the universal god-force—in my case, my ancestors. As the mind transcends the ordinary, a sense of peace takes over, a subliminal teaching asks us to listen. I listened in front of the unexpectedly blossoming cherry tree. To my delight, my listening skills were still intact. When the muses finished transforming my mind, myself now made divine (my god-self), I drove away to find a better parking spot and took care of my wellness by getting a massage. The universal god-force appearing to me that afternoon in the playground of Mother Nature is a powerful manifestation, which both Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza and elder Bernie Francis, an L’nu linguist, valorized despite being separated by centuries and an ocean.[7] From my own Indigenous perspective, the god-force is all encompassing: it lives and breathes through all life forms.

My generous ancestor, turned into a muse, gave me a poetic gift on that November day, one that later prompted me to write a poem in the L’nuk komqwejwi’kasikl language. To ignore the urgent promptings of my muse would be disrespectful, and to refuse a gift from my ancestors would be most ungracious. Prior to this momentous November day, I had often wondered when a komqwejwi’kasikl poem would emerge in my field of consciousness, a poem that would offer multiple learnings in the future. This miraculous poem kick-started a process: I would teach myself, and others, the complexity of an ancient language, a writing system that had never been part of my learning in the Canadian school system.

The L’nuk language has been described by my people as complicated and descriptive, with “many layers of meaning.”[8] The komqwejwi’kasikl poem expands on the complexity of our language, and it poses a bigger challenge: to learn as quickly as possible before it’s too late. Several elders who were fluent have already passed away. This process will forever re-consume the learning and writing experience for me, beyond my existence in this world. Yes, the komqwejwi’kasikl language has lit a fire within this artist.

The incipient poetic formation that catalyzed my creative inquiry transformed itself into the poem below. This process prompted me to recognize the interconnectivity of space, time, and creativity, unlocking what my elders describe as L’nuk epistemology and ontology.

Poetry as an Active Dialogue in the Space of Nm’ultes

From an existential perspective, my komqwejwi’kasikl poem connects me to the ancestral space-time through its embedding of my personal reflection in my ancestral language. When that happens, the ancestral spirit world descends into the vortex of my mind, rendering it a gathering place of Nm’ultes. This is the essence of a creative inquiry process I have come to define as Nm’ultes theory, an active ongoing dialogue occurring at multiple levels of reality. In my ancestral worldview, nothing happens without a dialogue, and Nm’ultes is an active, dialoguing-generating force, shaping the way I interpret the L’nuk way that transforms my own life today.

As Nm’ultes descends into my mind, I am thinking, perceiving, and feeling in my original language. When that happens, I find it very difficult to translate into English what I am experiencing as L’nuk ontology. Perhaps a more productive way to explain how the creative inquiry process progressed, and to demonstrate the complexity of the L’nuk language, is to present the poem that transpired—my first komqwejwi’kasikl poem—in English and in the L’nuk language two ways, phonetically and in the komqwejwi’kasikl script.

At the beginning of this process, I sifted through a komqwejwi’kasikl dictionary, examining the symbols with no instructions on how to use or read them.[9] Later, I learned that these “[h]ieroglyphic texts are composed of individual symbols (called glyphs) written horizontally from left to right. Each glyph represents a word in the Mi’kmaq language.”[10] You can see how they were used as maps. This intuition exploded in my Nm’ultes space-time creative endeavor. That November day, what lay before me was a komqwejwi’kasikl poem for the future and a clear understanding that learning the komqwejwi’kasikl written language will be a lifelong journey.

Interpreting the Nm’ultes Lens as a Child of a Residential School Survivor

The New Relation of Gaspesia (1691), which Catholic missionary Chrestien Le Clercq wrote near the territory of my great-grandparents, gave me “eureka” moments and insight into my people’s culture and language. This invaluable book became my original Nm’ultes document. It persuaded me to research the history of komqwejwi’kasikl and inspired me to write from an L’nu perspective. New Relation of Gaspesia is the autobiographical account of Le Clercq, whose mandate was to convert my ancestors to Christianity, and whose claim to have invented the komqwejwi’kasikl script needs to be invalidated:

Our Lord inspired me with the idea of them [the characters] the second year of my mission, when, being much embarrassed as to the method by which I should teach the Indians to pray to God, I noticed that some children were making marks with charcoal upon birch-bark, and were counting these with the finger very accurately at each word of prayers which they pronounced. This made me believe that by giving them some formulary, which would aid their memory by definite characters, I should advance much more quickly than by teaching through the method of making them repeat a number of times that which I said to them. I was charmed to find that I was not mistaken.[11]

I describe my soul’s purpose in this way: I am a poet on the lookout for a link to a Nm’ultes story, and because of that poetic quest, seeking knowledge that consumed my creative angst became normal for me. Many aspects of my own life, what I call my semi-autobiography, are essential to my encounters with Nm’ultes to acknowledge that my Nm’ultes epistemology stems from my need to understand my people and what they lived through, even from a priest who made baseless claims about our language.

When my siblings and I were still young, we were removed from our biological mother’s care. Her storyline had many missing Nm’ultes layers. She was a victim of the notorious Shubenacadie Residential School in Nova Scotia. Through no fault of her own, she and many other former residential school survivors had succumbed to their traumas, and like numerous survivors, she could not care for her toddler and three older children. This is difficult for me to write about because the memories of my mother’s story are like annotated bits and pieces of an unfinished jigsaw puzzle with missing Nm’ultes links.

Over the span of many years, I was very grateful whenever I met one of my biological mother’s closest friends. I knew they loved my mother because introductions were never necessary. The first thing they would convey is how much we looked alike, and then stories about her life prior to her illness would surface in the same conversation. I heard stories of her excelling as a post-secondary student on her way to becoming a brilliant teacher. She was a gifted poet, a whiz with numbers who worked at a bank; a close friend described her as a genius, a seer. When she was only a month shy of finishing her teaching degree, she traveled to Boston, Massachusetts, a destination for many L’nuk people seeking work, pleasure, or both. That was where she met my biological father, an L’nu from Natoaganeg, New Brunswick—the same man with whom she would have three children, ultimately never returning to complete her studies. It’s not right to begin telling a story and then end it with so little information but put yourself in my position: imagine learning about your mother’s life in snippets, many years apart.

The gift that would later emerge due to my birth mother was the Nm’ultes knowledge system, which academically and creatively functions as a source for my healing and for understanding what it means to be an intergenerational trauma survivor. This personal narrative that has kept resurfacing, articulated in bits and pieces, is the never-ending Nm’ultes story of a poet searching for the truth about the past, about my people’s language and cultural richness. Looking back, I recognize that my encounter with the way Nm’ultes takes form is a multilayered creative journey, spanning a lifetime and often intersecting between the worlds of a poet who lives off reserve and just wants to go home to her First Nations community.

Parts II and III will be published in the fall.

Michelle Sylliboy is Assistant Professor in the Art Department and in the School of Education at St. Francis Xavier University, Nova Scotia, Canada, on unceded L’nuk territory

[1] Mi’kmaw is an erroneous transliteration of my people’s name, which is actually L’nuk. I am L’nu (singular); L’nuk describes the nation or more than one L’nu person.

[2] Murdena Marshall and David L. Schmidt, eds., Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America’s First Indigenous Script (Halifax, NS: Nimbus Publishing, 1995), 2.

[3] Chrestien Le Clercq, New Relation of Gaspesia: With the Customs and Religion of the Gaspesian Indians, transl. W. F. Ganong (Toronto, ON: The Champlain Society, 1910).

[4] Lillian B. Marshall, Potlotek (Chapel Island), Nova Scotia, Mi’kmaw Nation, personal communication, ca. 2018.

[5] For publication clarity, the komqwejwi’kasikl script and accompanying English translations were redrawn, by hand and digitally, by Jessica Mensch and Jocelyn Li, based on Karina Alfarano, Concetta D’Ippolito, Daniella Orbita, and Rosetta Tiro, Mi’kmaq Dictionary (unpublished manuscript, 1999).

[6] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Honoring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015), 2: https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf (accessed June 11, 2022).

[7] Baruch Spinoza, Improvement of the Understanding, Ethics and Correspondence, trans. R. H. M. Elwes (London: M. Walter Dunne, 1901), 80; Trudy Sable, Bernard Francis, Roger J. Lewis, and William P. Jones, The Language of This Land, Mi’kma’ki (Sydney, NS: Cape Breton University Press, 2012), 30-31.

[8] Sable et al., Language of This Land, 13.

[9] Alfarano et al., Mi’kmaq Dictionary.

[10] Marshall and David, Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers, 4.

[11] Le Clercq, New Relation of Gaspesia, 131.

Cite this note as: Michelle Sylliboy, “Artist’s Notes: Nm’ultes is an Active Dialogue I: Reclaiming Komqwejwi’kasikl,” Journal18 (June 2022), https://www.journal18.org/6399.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.