Editor’s Note: The last of three installments, this intervention by L’nu interdisciplinary artist, poet, and scholar Michelle Sylliboy offers an Indigenous perspective on the ongoing impact of Nouvelle Relation de la Gaspésie (Paris, 1691) by French missionary Chrestien Le Clerq, which is part of the eighteenth-century colonial archive of Indigenous-settler relations on L’nuk territory, also known as Mi’kma’ki. In part I and II, Sylliboy traced her healing journey, as an intergenerational trauma survivor, from reclaiming the komqwejwi’kasikl language to embracing the Nm’ultes knowledge system. In this third part, she reflects on the possibility of reconciliation and uses the poetic gift of her ancestors as she connects the pieces.

Michelle Sylliboy, Ntininaq / Our Beings / Nos êtres, 2019. Wasoqitestaqn / Digital photography / Photographie numérique, 86.4 x 58.4 cm. © Michelle Sylliboy.

The gateway towards potential healing was set in motion at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) event in Vancouver, which my late adopted father and thousands of elders attended. With the conference and all the family dynamics taking place only a block away from my home, my existential crisis unraveled. This was the year I understood why being in the dark about the impact of residential schools had been necessary and why the Nm’ultes story had unfolded the way it did. Researchers in psychology and neuroscience have found the following:

In addition to their increased exposure to stressors, IRS [Indian residential school] offspring also seem to be more affected by stressors. In this regard, the occurrence of depressive symptoms was independently related to adverse childhood experiences, trauma experienced in adulthood, and levels of perceived discrimination, and in each case, symptomatology associated with these stressors was greater among IRS offspring compared to non-IRS adults in the study carried out with First Nations adults from across Canada…. It is known that stressful events may result in the sensitization of biological stress systems…so that behavioral and biological responses to later stressors are exaggerated.[1]

As a volunteer at the Vancouver TRC event, one of my duties was helping attendees at the registration desk. There, I met survivors from across Canada and learned a great deal about my late father and why he behaved in certain ways. It felt as though I was registering my father over and over for two days. I didn’t need to sit through hearings or ask him questions to understand him or my biological mother. It was through these encounters with total strangers that it became obvious my personal healing had to begin as soon as possible. Yet again, however, I was not ready. How does one heal from trauma when it is as fresh and raw as if it had happened only yesterday? Knowing and doing are two separate things:

If words touch me unkindly

The deeds I fling to the wings.

Though my heart lies uncaring briefly

The spirit rises in anger.

So, I trim myself to the storm

Until it melts away.

Then I put my best foot forward

Breeding me the woman of stone

And brush away the vacant trivia.

Firmly rooted,

The touching has not yet

Blemished my heart completely.[2]

I knew I needed to undergo healing, yet I could not do it, and I abandoned the journey once again. These and other long-overdue issues festered like an old wound that would not heal. I quietly returned the thoughts and feelings to my Nm’ultes folder until I was ready.

In the last two years of the TRC’s community work towards reconciliation, I noticed a pattern of response that kept surfacing within myself and many children of survivors in the arts. The deeply entrenched Nm’ultes paradigm of unwanted reconciliation was common amongst my peers, other children of survivors, more than I had expected. When the space was available to speak our truths, I noticed that artist children of survivors were reluctant to enter the vortex of what reconciliation represented within the First Nations arts community. Anger and frustration surfaced amongst my peers. It was obvious that we were, and still are, hurting and on the verge of a precipice, wanting to escape from the vortex of the old reality that has held us hostage since birth. When we artists responded, it was necessary for us to articulate to the community at large that we experienced the TRC dialogues as arbitrary. We felt we were being forced to reconcile without a plan. Who shared the Nm’ultes box that held our secrets? As victims, how could we take part in a constructive dialogue when we had not reconciled with our families or with ourselves as the first generation of intergenerational survivors? The Nm’ultes box that contained the necessary healing had to be handled with caution and only if we were ready. What the community and country needed and still need to hear is this: Some of us are not ready to reconcile just yet. We need time to adjust, to understand our unwanted inheritance, and to know with whom we are reconciling.

Like many children of survivors across Canada, I did not know my biological mother and adopted father were victims of residential school trauma until stories across Canada emerged. To my knowledge, the first elder within my nation to disclose the impact was author Isabelle Knockwood. Her 1992 book, Out of the Depths: The Experiences of Mi’kmaw Children at the Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia, was a shocking revelation.[3] Looking back, I remember that my elders, including members of my immediate family, felt hurt by her disclosure. A plethora of emotions, including anger, frustration, and embarrassment, emerged and imploded. These were stories difficult to hear, let alone absorb. As an educated adult whose process of decolonization was occurring rapidly, I often experienced emotional baggage that I did not recognize. These revelations by my elders took me many years to understand, let alone connect to my healing and creative process, one that now held a bigger Nm’ultes challenge. While some survivors of residential schools moved on and were given the tools to start their healing processes, not all were so lucky. Some, such as my biological mother, could not exist in this world we accept as reality. Many lived out their days never having the ability to tell their stories to the world for various reasons: mental health, incarceration, homelessness, and so on.

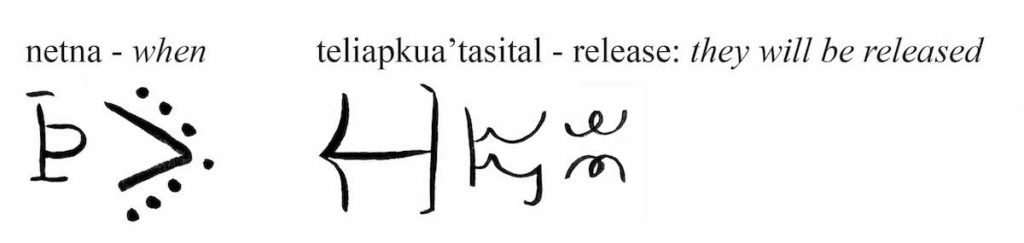

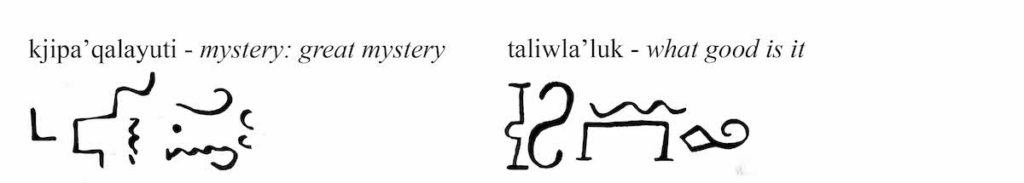

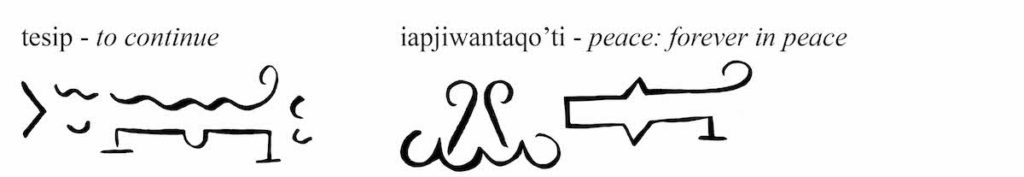

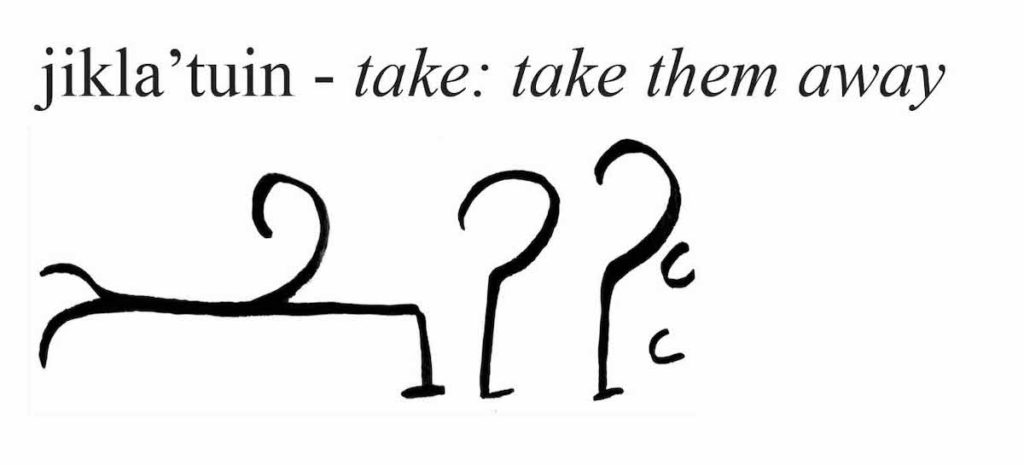

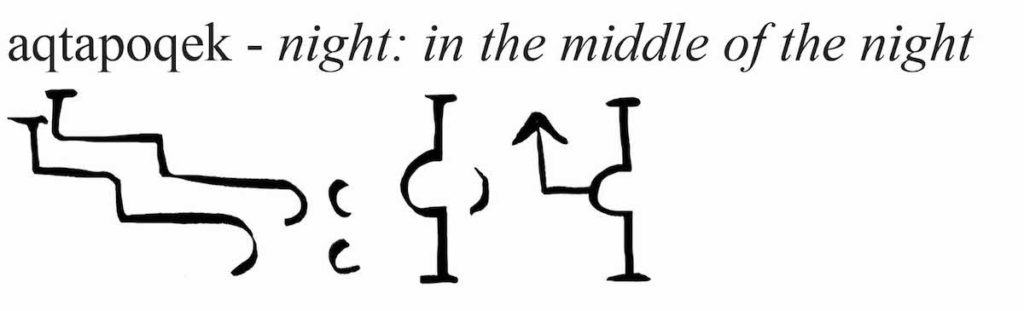

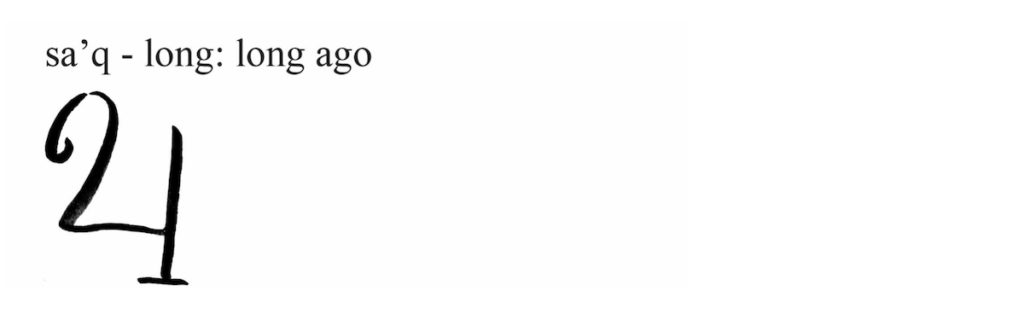

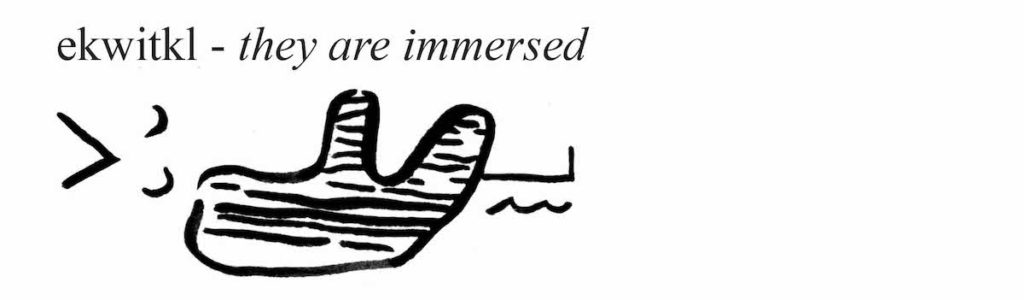

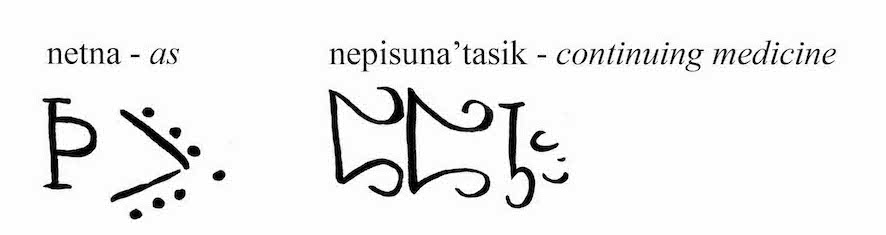

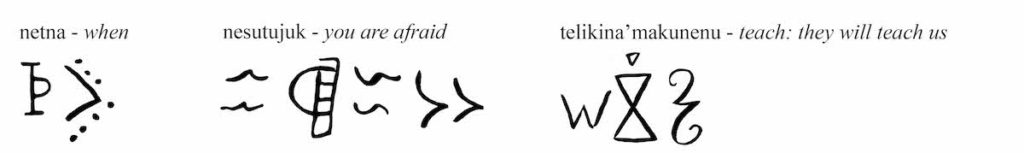

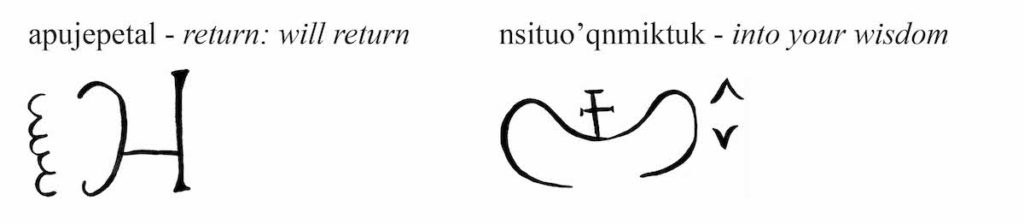

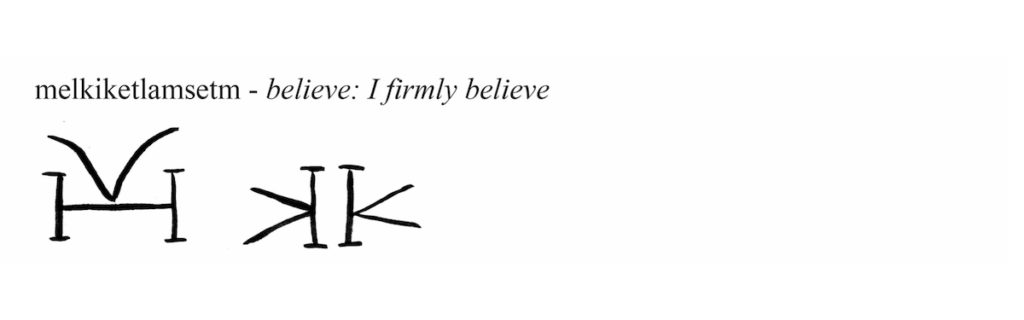

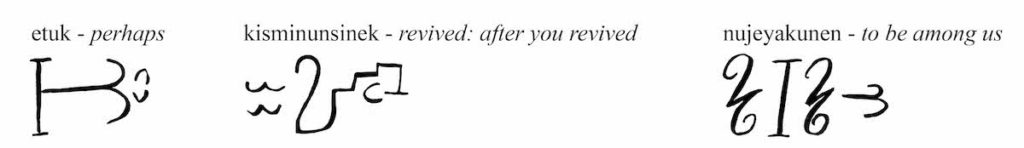

Recognizing that I shoulder these impacts as a child of a residential school survivor, how do I communicate my pain and suffering and undo the residual effects of trauma? I have addressed the missing links by using my personal Nm’ultes narrative to bring out the voice that needed to be heard. This has included speaking and writing about losing my family, community, and cultural connections for many years. Having the opportunity, back in 1988, to learn about the komqwejwi’kasikl language became the catalyst for piecing together numerous Nm’ultes gaps and missing links. I used creative inquiry methods to reclaim the komqwejwi’kasikl language from French missionary Chrestien Le Clercq’s New Relation of Gaspesia (Paris, 1691), while unleashing the suppressed and hidden fragments of my personal, familial, and cultural history, all of which are attached to the loss of land and cultural ties to family and community.[4] With the help of Nm’ultes, I have been able to analyze my history of trauma and to use the komqwejwi’kasikl language to acknowledge how my mind connects to what was removed and what was restored.

The komqwejwi’kasikl poem “Ankite’tmkl – We Are Thinking of Them” is an expression of my worldview. The psychological effect that the environmental water protectors had on me is a rooted connection to the missing Nm’ultes story that my history of trauma could not destroy. When a member of any community is disenfranchised for protecting the environment, we all hurt as human and more-than-human beings who share the same earth. My understanding of Nm’ultes reminds me that there is no easy way to write about adversity. It is as though my mind deliberately plays tricks on me and teaches me in dreams, conversations, and visions, night and day. This is L’nuk ontology and epistemology at work, what I have been calling the Nm’ultes paradigm. It also teaches me at protest marches and at dinner parties, and while I am waiting for a parking spot.

The komqwejwi’kasikl poem is the L’nuk landscape stripped from us often at birth. If we allow as activism the writing of a komqwejwi’kasikl poem that will change the course of my personal history, and possibly my culture’s history, then I am an activist. My komqwejwi’kasikl poem is a historic first using creative inquiry methodology. It expands my people’s current use of the komqwejwi’kasikl language. The Catholic Church was first responsible, through Le Clercq, for publishing the komqwejwi’kasikl prayers. It was my ancestors and elders, however, who kept it from disappearing. Their role in preserving the komqwejwi’kasikl language must be acknowledged, and their role in our shared history must be vindicated. The L’nuk people used the komqwejwi’kasikl symbols long before first contact with the colonizers.

My goal is not to rewrite history with more theories, but to write, with new intentions, a positive account acknowledging that we are a culture of storytellers and writers—past and present—with a complex komqwejwi’kasikl language system. It is imperative that we recognize the negative perceptions carried on by the colonial archive of the early days of contact. When you read, and you will, Le Clercq’s New Relation of Gaspesia, you will witness his blatant refusal to respectfully acknowledge my ancestors and the way Indigenous peoples have been repeatedly spoken of. My personal story is raw, but it’s mine to tell and share as I please. My ancestors had no idea they were written about in such a way.

Recognizing How L’nuk Language and Culture Connect with My Nm’ultes Analysis

The komqwejwi’kasikl language, once used as maps and tribal records, is a complex and complicated language whose origins lie directly in the land.[5] This is true of the spoken language as well. L’nu elder and linguist Bernie Francis writes:

The language of this land, Mi’kma’ki, explores how the Mi’kmaq of the Eastern North America came to mirror and express their unique relationship with the landscape they call Mi’kma’ki, the territory of the Mi’kmaq. This language includes the legends, songs, dances, and other forms of cultural expressions—forms that mirror and communicate the rhythms and sounds, movement and patterns, and seasonal cycles of the animals, plants, winds, waterways, and stars across the skies of Mi’kma’ki. The Mi’kmaq verb infinitive, weji-sqalia’timk, is a concept deeply ingrained within the Mi’kmaq language, a language that grew from within the ancient landscape of Mi’kma’ki.[6]

I wanted to use my language the same way my ancestors did prior to contact. I wrote a komqwejwi’kasikl poem to coincide with current events and communicate what is happening with the land. Was I successfully transforming the komqwejwi’kasikl language into a modern-day poem, away from the Catholic influence? Who knows! The muse works in mysterious ways!

Into a deeply worded ceremony of blood, memories centered on each passage like crackling leather footsteps banging against an earthly wall, appearing from the depths of trauma. The same description presented orally can be said of the L’nuk komqwejwi’kasikl language. What is spoken and written comes from my people’s long history with the land. The language, whether spoken or written in the komqwejwi’kasikl form, is a bridge to truth and an underlying connection to how Nm’ultes unleashes the potential dialogues we humans crave. For the L’nuk, the act of existence is about the Nm’ultes dialogue. As L’nuk people, we need to communicate with each other the quintessential Nm’ultes theory of existence. Language is medicine: it activates the creative healing dialogue.

The intergenerational impact of residential schools both enlightened and challenged my ego and my conflicted worldview. Processing this double meaning of Nm’ultes took time. It was like having a sealed envelope that refused to open because the secrets within were too great a burden for me to bear. Without the proper understanding of or patience for an epic journey, I had been a poet without a compass. But I wasn’t anymore now that I had uncovered how the Nm’ultes heritage and paradigm had been unleashed in my search for the komqwejwi’kasikl language.

As a poetic warrior with a personal cause, I have met the challenge of healing head on. I no longer harbor blame towards anyone. From where I stand today, everything took place for a reason. I unlearned and undid the harm to decolonize what I came to know as an L’nu artist: that dreaming, or dancing, is not a metaphor but part of my cultural epistemology and ontology—a statement I can offer without guilt as an academic scholar who takes the measure of an academic discourse that poses different worldviews. The same process of opening to otherness and traveling across differences to reach into the other occurs here, too. We are here to learn about each other’s worldviews. What are all these different worldviews but corresponding apparitions of the reality we call daily life?

We must remind ourselves that we share the connective tissues of all earth’s beings, as we eat the same foods from the same gardens and oceans, even though they may be packaged and sold at different superstores. This is not only a dynamic political statement but also a reminder about practical healing activism as we challenge the way history is being told, and by whom.

Nm’ultes is an Active, Ongoing, Multiontic Dialogue: A Non-concluding Thought

Nm’ultes can have multiple outcomes. Nm’ultes is personal. Nm’ultes highlights how everything is interconnected. On a good day, Nm’ultes allows you to walk into the future like a warrior with a purpose.

My Nm’ultes journey is the L’nuk worldview experienced through my eyes as I acknowledge that the unending metaphor is part of our creative process and journey. Nm’ultes has no ending. Nm’ultes is not a race to a finish line. It walks like the bear spirit that has guided me since birth. Nm’ultes is in the roots of a tree that held me in the ground with their strength, in the wings that allowed me to see ahead as my ancestors cleared a path that often changed at a moment’s notice with a purpose in mind. Such was my encounter with cherry blossoms on a chilly November day.

Nm’ultes is an active dialogue, a never-ending journey that takes you to places unbeknownst to your human existence, which is why I call it “multiontic.” This is L’nuk ontology at its finest. Nm’ultes is a personal worldview-in-action that transcends into places we have no control over, such as the outcomes of philosophical propositions, or ethical guidelines never written but practiced daily. The goal of Nm’ultes is to arrive at your destination intact, either spiritually or physically, but always ready for the next phase of your existence. The Nm’ultes from within is the intergenerational survivor waiting for my next Nm’ultes moment on a journey that will carry me to the threshold of interconnected dialogues through creativity, sadness, and laughter. If I am lucky, an interesting journey to the Nm’ultes pathway of rediscovery awaits me. The Nm’ultes encounter and journey, whether repetitive or unpredictable, is always transforming. The process of such an encounter and journey is an ongoing catalyst amid reconciliation with oneself or with others along the path of being seen and discovered in one’s public and private lives. In this process, mystery abounds.

Nm’ultes, when we are ready, will transform itself into a gift from the universal god-force and, if we are lucky, our mind will wander to the next world.

Nm’ultes Poetic Stage of Discovery

First breath under the sun

was flamboyant behavior

nestled against the backdrops of our

mothers shared blood

a metaphor

cloaked between time frames

as the easel approaches inspiration

colorful vibes

become infused in our veins

I am partridge growing as we speak

I am alder breathing life into salmon

I am spruce grounded at my feet

ancestral knowledge echoing rhythms

beyond this world as

a catalyst to Ishtar her strong willed

spiritual companion awaits her decision

there is a dream within a dream

that keeps resurfacing

elders’ visit: writers, healers,

grandmothers, surrogate aunties

all come to visit

everyone reminding me

solitude is engaged

to my effortless landscapes of tomorrow

restoring a consciousness held in captivity

hovering between layers of malleable pieces

responds with considerable feeling

like a sequence forward backward with no proof

we are admired from afar

as travelers without a compass reciting

un-coordinated appointments

conveying a story

chronologically misplaced on purpose

to smell the ocean by your bedside

creates an openness of gratitude

reporting to the gods we seek

as our significant other in dreams

as we honor what is necessary

by returning to the beginning

sacrificing holding on to what is meaningful

believe when the sun sets on the other side

secrets are revealed

Nm’ultes aqq Welalioq

Michelle Sylliboy is Assistant Professor in the Art Department and in the School of Education at St. Francis Xavier University, Nova Scotia, Canada on unceded L’nuk territory

[1] Amy Bombay, Kimberly Matheson, and Hymie Anisman, “The Intergenerational Effects of Indian Residential Schools: Implications for the Concept of Historical Trauma,” Transcultural Psychiatry 51, no. 3 (2014): 326-327.

[2] Rita Joe, Song of Rita Joe: Autobiography of a Mi’kmaw Poet (Wreck Cove, NS: Breton Books, 2011), 62.

[3] Isabelle Knockwood and Gillian Thomas, Out of the Depths: The Experiences of Mi’kmaw Children at the Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia, 2nd ed. (Lockeport, N.S: Roseway, 1992).

[4] Chrestien Le Clercq, New Relation of Gaspesia: With the Customs and Religion of the Gaspesian Indians, transl. W. F. Ganong (Toronto, ON: The Champlain Society, 1910). See Part I for my discussion of this text an my work reclaiming the komqwejwi’kasikl language Le Clercq culturally appropriated.

[5] Murdena Marshall and David L. Schmidt, eds., Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America’s First Indigenous Script (Halifax, NS: Nimbus Publishing, 1995), 4.

[6] Bernie Francis in Trudy Sable, Bernie Francis, Roger J. Lewis, and William P. Jones, The Language of This Land, Mi’kma’ki (Sydney, NS: Cape Breton University Press, 2012), 17.

Cite this note as: Michelle Sylliboy, “Artist’s Notes: Nm’ultes is an Active Dialogue III: Nm’ultes Will Return into Your Wisdom,” Journal18 (January 2023), https://www.journal18.org/6669.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.