Marie Antoinette may be a person—and name—known by many, but she is also one laden with a series of inherent paradoxes. Expected to support domestic luxury industries and dress in a manner befitting a French queen, she was nonetheless pilloried for her spending. And while her life was populated with extraordinary, shimmering displays of wealth, this opulence ultimately stood in sharp contrast to the queen’s gruesome end. Certain anecdotes from her lifetime—the required clothing change at the Austrian-French border, the Affair of the Diamond Necklace, her supposed final words and letter, and infamous (if apocryphal) “let them eat cake” quotation—are oft-repeated, yet other details of her life and legacy require further teasing-out.[1] Marie Antoinette Style, the publication accompanying the Victoria & Albert Museum’s major exhibition of the same name, which opened September 20, 2025, spans both the lesser-known and most publicized aspects of her life. With its myriad dimensions and creative subtleties, the exhibition catalogue, reviewed here, explores the dualities of the last queen of France, more accurately capturing her essence and style—then and now—in the process.

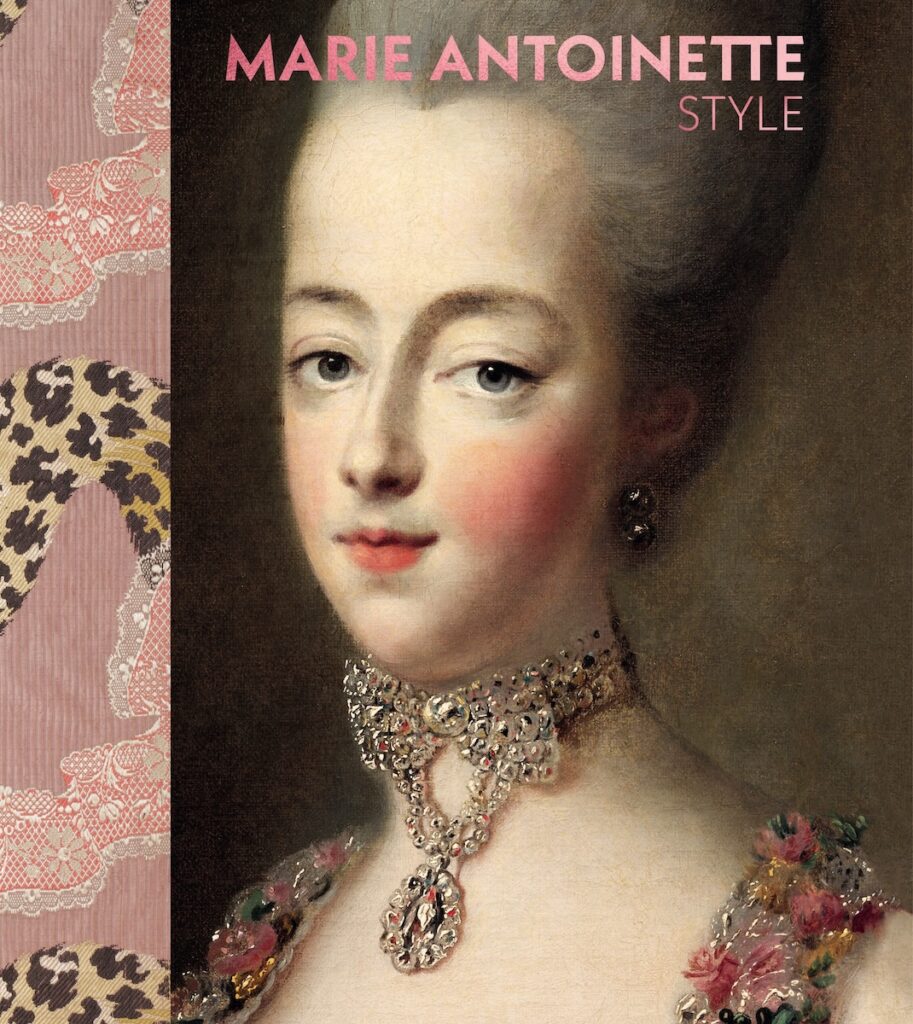

The publication itself, edited by curator Sarah Grant, makes clear from the outset that as an object it is another example of “Marie Antoinette style.” The cover, like numerous images later included in the well-designed publication, consists of a juxtaposition: in this case, a portrait of Marie Antoinette bordered by an image of a 1760s French textile from the V&A collection (Fig. 1). This brocaded silk fabric from the eighteenth century combines curling ribbons of lace and leopard-print tails on top of a pale pink striated ground. While this layering of a brocaded textile and a painting, and the framing of one museum-worthy work against another, are both deserving of further analysis, the design of the cover speaks to an aesthetic embodied by Marie Antoinette that is enduringly relevant today and that combines feminine superlatives of luxury and rhythmic juxtapositions. These contrasts persist throughout the text. To give just one subsequent example, bejeweled shoe heels are mentioned at the close of Vincent Meylan’s contribution to the volume, entitled “Queen of Sparkle,” which leads immediately into a chapter that touches upon contemporary cottagecore.[2]

The timely impetus for this exhibition and book are ostensibly the 270th anniversary of Marie Antoinette’s birth and the recent reappearance of some of the queen’s jewelry, pieces of which were sold in 2018 and 2021 at Sotheby’s and Christie’s, respectively. As V&A director Tristram Hunt notes in his foreword, the show is also the first British exhibition dedicated to Marie Antoinette.[3] This is arguably something of a surprise, as the last queen of France was both a subject of rapt attention in Britain and possessed a considerable affinity for English style herself (notably, numerous contributors to the book reference Anglomania).

But Marie Antoinette, as both a globally famous figure and one who embodied inequality, is also a fitting topic for 2025, albeit perhaps not one that can be remarked upon in those exact terms within the publication. Grant’s introduction highlights the magnitude of Marie Antoinette’s contemporaneous fame by opening with the queen’s mother, Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, warning her daughter of how closely she will be watched at Versailles.[4] Of course, the relevance of that admonition endures, as the very existence of this book and exhibition proves that, even centuries later, the French queen remains under scrutiny. Overall, the introduction is an excellent preview of the book, and a piece of writing that concludes by deftly returning to Maria Theresa’s warning to her daughter and revealing its second element in the process: “do not…cause a scandal.”[5] This bifurcated quotation is especially apt for a book that both explicitly addresses Marie Antoinette’s visibility but is also brimming with suggestive undertones.

The book is interwoven with a sense of back and forth between the less well-known attributes of Marie Antoinette’s historical legacy and contemporaneous information about style and visual culture. A key and repeated touchstone is Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film, Marie Antoinette. Largely based on Antonia Fraser’s pioneering biography, Marie Antoinette: The Journey, Coppola’s film mixed anachronistic music choices, contemporary Ladurée macarons, and more in a manner that paved the way for subsequent productions such as Bridgerton, as Harriet Reed notes in an essay in the book.[6] The V&A publication and current exhibition appear to owe a large dept to Coppola’s film. But while Coppola’s Marie Antoinette is repeatedly praised in this book—Grant at one point calls the film “a masterpiece of its genre”—this elides the mixed reviews with which the film was initially met.[7] Reporting from the Cannes Film Festival at the time, Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott wrote in The New York Times, “Though no one called for the filmmaker’s head, ‘Marie Antoinette,’ Sofia Coppola’s sympathetic account of the life and hard-partying times of the ill-fated queen, filled the theater with lusty boos and smatterings of applause after its first press screening….”[8] Coppola and Fraser’s brief contributions to Marie Antoinette Style are welcome, if too brief, additions, considering their commanding influence on how Marie Antoinette has been understood and reinterpreted in the twenty-first century. Yet Coppola’s paragraph, which centers on the idea of goodness, or lack thereof, is slightly puzzling. What is more, this publication might have benefited from scholarly contributions from Caroline Weber, whose influential book, Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution, was also published in the early 2000s; from dress and textiles historian Rebecca Arnold, who has written on Coppola’s film; and from Anne Higonnet, whose book Liberty Equality Fashion: The Women Who Styled the French Revolution was published in 2024.[9]

The book is divided into two parts of unequal length. The first, which takes up approximately two thirds of the publication, looks at Marie Antoinette’s fashionable life while the second focuses on her stylistic legacy. That first section includes chapters on silk, shoes, fans (Fig. 2), and more, yet opens with an essay, “The Queen’s Private Apartments and the Petit Trianon,” which is an inspired choice. By giving this architectural site pride of place, the scene is literally set for subsequent information. Notably, author Hélène Delalex gives more weight to the refurbishment of Petit Trianon and the building of its nearby hamlet than to the changes made to the queen’s private apartments at Versailles. In this way, the reader is transported to the period that marked the end of Marie Antoinette’s story.

Nonetheless, the text successfully raises interesting points about the dynamics of taste that are not bound to a specific point in time, such as why there continues to be a propensity to refer to “Louis XVI style” when “Marie Antoinette style” might indeed be more accurate. When viewed from a wider vantage point, this book seems to open up the question of what might be the difference—in the public if not scholarly imagination—between eighteenth-century and Marie Antoinette style. Delalex notes of the latter: “If we had to define it, Marie Antoinette’s style would be above all a taste for lightness.”[10] While that makes sense within the context of Petit Trianon, which, with its simplified interiors and accompanying en chemise clothing, seems somewhat aligned with today’s penchant for “quiet luxury,” it seems doubtful that the average contemporary reader or exhibition viewer would ever truly take away a sense of “lightness” when confronted with a cacophony of Marie Antionette’s diamonds, silks, and shoes (Fig. 3).

While the aforementioned chapters on silk, shoes, and fans are somewhat expected, others on scent and letters extend the book’s remit to include the sensory and tangible. Grant contributed two chapters to this section: “The Perfumed Palace: Marie Antoinette and Scent,” which covers both the proliferation of perfume and issues with odors, and another chapter on the queen’s wardrobe. As interesting as the latter is, it cannot help but hint how else sensory experience could have been addressed in the catalogue. For its own part, “In Her Own Words: Marie Antoinette’s Letters” brims with details and includes insights about the queen, who at first appears vulnerable, but proactive in her final days. The veracity of Marie Antoinette’s letters, ongoing research efforts in this area, and the importance of understanding the queen “in her in own words,” are all topics that warrant further thought.[11] “Queen of Sparkle: Diamonds, Fashion, and Politics,” by Vincent Meylan, covers not just the infamous affair of the diamond necklace—in which the queen was falsely accused of refusing to pay for an extremely expensive commission—but also the importance and value of jewelry from the very outset of Marie Antoinette’s married life. The beguiling jewelry designs, one in gouache on paper, that are featured throughout make this chapter not only visually rich but also distinct from the photographs and objects embedded elsewhere.[12] What is more, “Toiles de Jouy: Marie Antoinette and Cottagecore,” by Silvija Banić and Jessica Harpley, touches relatively briefly on the queen’s proclivity for pastoral clothing and the titular “cottagecore” style—a contemporary preference for countryside aesthetics—before turning toward the eighteenth-century printed cotton fabric known as “toile de jouy” due to its derivation in Jouy, France. While this distinct and enduring French printed cotton is no doubt fascinating, the book would have benefitted from a greater focus on Marie Antoinette’s own controversial fashion evolution from wearing silk grand habits to preferring white muslin robes en chemise.

Within the book’s second section, the chapter, “Marie Antoinette and Sapphic Love,” written by V&A director of exhibitions Daniel Slater, stands out as an exemplary chapter in terms of the substance and structure of its writing. Slater discusses the voyeurism, “slander, violence, and lust” that underpinned the lesbian images of Marie Antoinette that circulated during the late-eighteenth century.[13] By entertaining various possible explanations for these images before arguing that the depictions are fundamentally about their viewers’ ability to wield power over the queen, and to some extent, possess her, Slater deftly imbues his text with a sense of drama. He concludes with another excellent insight, writing: “[These tribade tales] remain perpetually rumors, stories, secrets to be ‘uncovered’ again and again, not so that we can fall under Marie Antoinette’s spell but so that she can fall under ours.”[14]

Other chapters in this section are fitting pieces in the puzzle of the French queen’s legacy. Those on Napoleon III’s wife, Empress Eugénie (1826-1920), and fancy-dress balls, for instance, are informative, while others, on the period 1910–1940 and Madame Tussaud, respectively, are more of a surprise to come across given their temporal distance from the time of Marie Antoinette. While “A Queen in Fashion” by Oriole Cullen is less clear in its focus, others, such as a chapter dedicated to performance, are very welcome at this point in the book, as the themes they discuss resonate with the topics discussed by earlier contributions on fans, letters, and the queen’s visibility. “Let Them Eat Cake,” by Colin Jones, largely addressees the queen’s famed, if inaccurate, utterance, yet would have benefited from a broader consideration of food and dining at the French court. Certainly, dining customs and tableware could be considered integral to Marie Antoinette style, from the historic manners, porcelain, and dishes to the modern-day popularity of Coppola-approved Ladurée macarons.[15]

If Marie Antoinette’s life was a fairytale turned nightmare, and one whose trajectory feels clear with the benefit of hindsight, then the mode de la reine—as this book proves—has followed a decidedly different course. Today, an interest in Marie Antoinette style is perhaps synonymous with an interest in eighteenth-century style at its apex of femininity, excess, and beauty for beauty’s sake. After all, while the decades prior to the queen’s arrival in France as well as the subsequent century both brimmed with over-the-top opulence, these moments have arguably not retained the same level of stylistic relevance. As the chapter topics, images, and layouts of this publication all prove, elements of the queen’s dress, broadly defined, were often combined to great effect and in a manner which underscores Marie Antoinette’s layered, multifaceted nuance. This might be the best encapsulation of the book’s overarching viewpoint: that the late French queen’s life deserves sympathy, and that her continued stylistic relevance is something to examine and celebrate but not to significantly complicate. In doing so, Marie Antoinette Style is poised to appeal to eighteenth-century scholars and museum gift shop visitors alike. It will be up to future scholars to disentangle Marie Antoinette’s stylistic legacy from our current (predominantly pink) princess culture; to determine why she appears to be of greater interest at a moment of increased inequality; and to add a new chapter to the literature that goes beyond Fraser, Coppola, and now Grant’s significant contributions.

Madeleine Luckel is a PhD student in the Department of Art History & Archaeology at Columbia University in New York City, NY

[1] Colin Jones, “Let Them Eat Cake.” Unless otherwise noted, all citations for chapters refer to Sarah Grant, ed., Marie Antoinette Style (V&A Publishing, 2025).

[2] Vincent Meylan, “Queen of Sparkle: Diamonds, Fashion and Politics,” 110.

[3] Tristram Hunt, “Foreword,” 8.

[4] Sarah Grant, “Introduction: Marie Antoinette Style,” 13.

[5] Grant, “Introduction,” 32.

[6] Harriet Reed, “Marie Antoinette Performed,” 273.

[7] Grant, “Introduction,” 26.

[8] Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott, “‘Marie Antoinette’: Best or Worst of Times?” The New York Times, Cannes Journal, May 25, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/25/movies/25fest.html (accessed October 21, 2025).

[9] See Caroline Weber, Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution (Picador, 2007); Rebecca Arnold, “The New Rococo: Sofia Coppola and Fashions in Contemporary Femininity,” in Rococo Echo: Art, History and Historiography from Cochin to Coppola, ed. Melissa Lee Hyde and Katie Scott (Voltaire Foundation, 2014), 295–312.

[10] Hélène Delalex, “The Queen’s Private Apartments and the Petit Trianon,” 51.

[11] Catriona Seth, “In Her Own Words,” 178.

[12] Meylan, “Queen of Sparkle,” 93–110.

[13] Daniel Slater, “Marie Antoinette and Sapphic Love,” 233, 234.

[14] Slater, “Marie Antoinette and Sapphic Love,” 239.

[15] Oriole Cullen, “A Queen in Fashion,” 256; Harriet Reed, “Marie Antoinette Performed,” 268.

Cite this note as: Madeleine Luckel, “Marie Antoinette Style: An Exhibition Catalogue Review,” Journal18 (November 2025), https://www.journal18.org/8031.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.