Roundtable Participants: Kate Fullagar, Miriama Bono, Pauline Reynolds, Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones, Peter McNeil, Monica Anke Hahn, Carl Vail, Peter Brunt.

In March 2023, the longstanding battle for ownership of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Portrait of Mai (c. 1776) was resolved (Fig. 1). After more than two decades of struggle to retain in public hands the celebrated painting of the first Pacific Islander to visit Britain, it was bought by a consortium of art foundations, including the National Portrait Gallery and the Getty Foundation. It will now spend equal time in London and Los Angeles. The purchase price of £50 million was by far the highest paid for an eighteenth-century British artwork, the result of ever-rising hype around the portrait since its sale in 2001 to a private buyer for £10.3 million.[1]

The length of the battle to regain this painting, as well as the substantial price-tag, has prompted numerous discussions about the legacy of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), the value of eighteenth-century British art, and the role of the Pacific in imperial and world history. It has undoubtedly lifted Reynolds’s reputation, from the fondly remembered if never highly exalted inaugural president of the Royal Academy to the “iconic” creative of the eighteenth century.[2] Once rarely noted in the annals of Reynolds scholarship, the Mai portrait after 2001 became regularly cited as a “masterpiece” and his “most famous painting.”[3] The large-scale portrait of Mai (c. 1753–79), a Raiatean man who traveled to Britain from Tahiti with Captain James Cook, was also embraced as a counterpoint to the worst aspects of imperialism, apparently proving that British relations with other races in the eighteenth century could be thoughtful, and even “positive.”[4]

What has been too often neglected is the sitter himself—Mai. While most observers of the portrait mention Mai’s two-year stay in Britain from 1774 to 1776, courtesy of James Cook’s second returning Pacific voyage, they usually skip over Mai’s motivations or post-visit life. Mai was around twenty-one years old when he secured a berth on Cook’s expedition. He had known about European arrivals in his archipelago since the first visit by Samuel Wallis in 1768, as later became evident from accounts of Cook’s crew. He had been inspired since that date to go one day to the land of “Beretane” because he understood it to be a land of exceptional firepower. As he often told companions in Britain, he wanted some of that mana (power) to help pursue a local war in his native Raʻiātea (near Tahiti) against invading Bora Borans.[5]

Without knowledge of Mai’s intensely Indigenous-centered history, it has been too easy for British observers—ever since 1774—to make him perform whatever roles they wish for him: “noble savage,” muse to genius, and now imperial redeemer.

In October 2024, a year and a half after the momentous purchase of Reynolds’s Portrait of Mai, I (Kate Fullagar) convened a workshop in Canberra, Australia, of scholars and creatives interested in exploring further all that had not yet been amplified about this painting. The event was part of my commitments as the inaugural Sir William Dobell Visiting Chair at the Australian National University. I was delighted to include art historians, intellectual historians, and artists, and I was especially grateful to have Islander Professor Peter Brunt provide the keynote entitled, “Turning British Art on Its Head.” Together with seven of the participants, including Brunt, we have reproduced here something of that workshop conversation in roundtable form.

—Kate Fullagar

Kate Fullagar: Let’s start with curator Miriama Bono, who joined us via Zoom from Tahiti. Miriama, your paper started with the premise that Mai is haphazardly known among Tahitians. Can you sketch for us something of how Mai is remembered today at home?

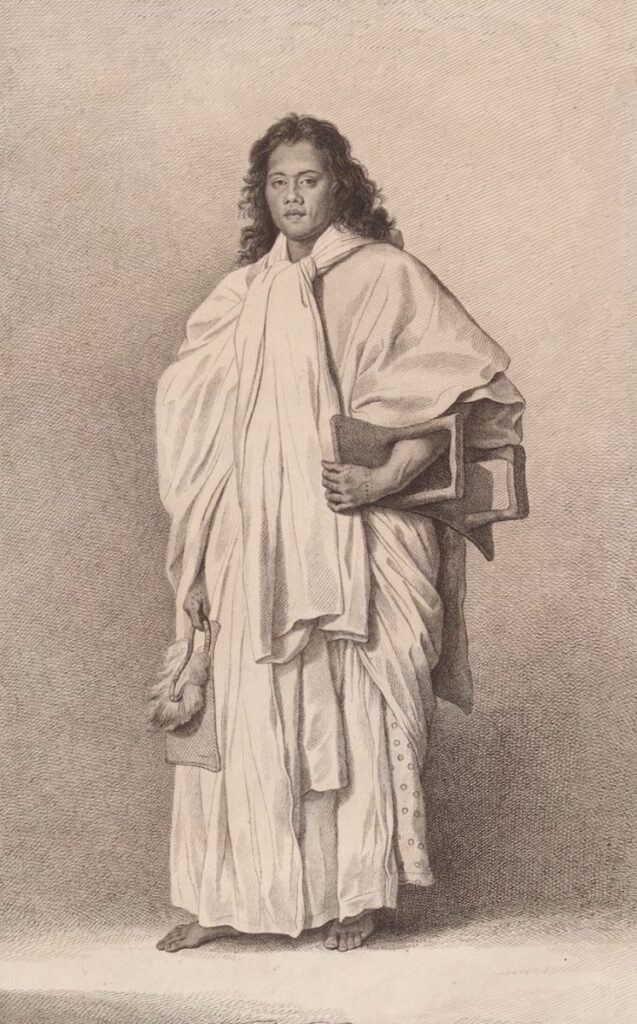

Miriama Bono: Of all the Islanders who traveled with the Europeans, Mai is the one for whom we have the most information and certainly the one with whom Tahitians can tangibly connect, as objects that once belonged to him are still in Tahiti today. His portraits are relatively well known, and Bartolozzi’s engraving is frequently used to illustrate this period (Fig. 2). But paradoxically, although Mai is certainly the easiest to imagine, he as a person remains relatively unfamiliar to a large proportion of the population, especially young people, who have heard more about the navigator and expert Tupaia (c. 1720–70) than Mai.[6] A play by Titaua Porcher, Oh my! Omai, recently performed in Tahiti with some success, has put him back on stage, with an original and touching perspective.[7] According to the author, she was surprised that the younger generation knew so little about him. So I’d say that while his face is relatively well known in Tahiti, his story is less so.

Kate Fullagar: What does the recent purchase of Reynolds’s painting of Mai mean to you personally?

Miriama Bono: The acquisition of the portrait by British art institutions and the Getty Museum is spectacular, since it costs far more than Polynesia could ever afford for its heritage. As an artist interested in questions of heritage and contemporary interpretation, I’m very interested to see how this will play out in the years to come. In a way, it puts the spotlight on Tahiti, and I hope that visual artists, writers and sculptors will have the opportunity to express a contemporary vision of the legacy of Mai, but also of Tupaia and other forgotten figures of our history. I hope that if artists have the opportunity to explore these subjects, it will not only make these characters better known in Tahiti, but also highlight Polynesian talent, which I think is far too little appreciated. Apart from evoking the myths of paradise, we’re unfortunately not very visible.

Kate Fullagar: Tapa-maker Pauline Reynolds, also of Tahitian descent, joined us in person from Norfolk Island. Pauline, you recently visited Reynolds’s Portrait of Mai in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG)—can you tell us about that experience?

Pauline Reynolds: In April 2024, I was in the UK for a project with Perth Museum in Scotland. My daughter met me in London, and the first thing we did was visit the NPG—it seemed the decent thing to do—to visit Mai and to pay our respects. We saw the portrait as Mai-the-person. I am an historian, and my daughter just finished her degree in Pacific Studies and is a poet; so, as scholars, creatives, and Islanders, we are both constantly walking through multiple worlds and paradigms, walking back and forward through past and present. Standing together at the NPG that day took us to Raʻiātea, where both Mai and my children were born. Raʻiātea is also where the prophets and priests first predicted the enormous changes that would happen in Mai’s time. We thought of Mai’s family seeking refuge in Tahiti after the invasion of Raʻiātea by warriors from a neighboring island. We thought of his life on Huahine, the land where my tupuna (ancestors) come from. We felt Mai’s courage as he stepped on board Cook’s strange expedition headed for England, and then his equally courageous return. We saw him in this portrait, far from home, an exile, an adventurer, wearing layers and layers of barkcloth, never ever being as warm in England as he was back home.

Kate Fullagar: Your presentation was a revelation to many of us since it included touchable examples of new and historic tapa—what does Reynolds’s portrait of Mai mean for your project of tapa creation?

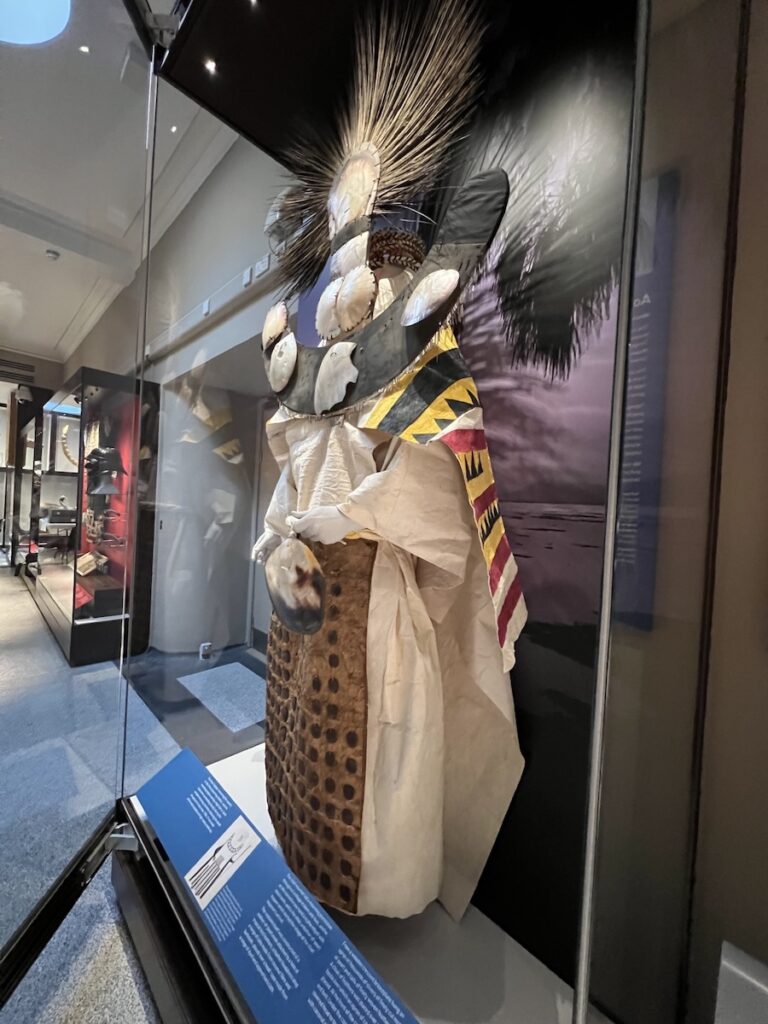

Pauline Reynolds: In the portrait I saw a complex layering of barkcloth, of history, of human connections, of colonial representations, but also of courage and beauty. I am a tapa artist, and this practice complements my scholarly work. I create replicas of historical barkcloth (also known as tapa or ’ahu), not just for the sake of replication, but to get closer to the worldviews of the society that created the originals, and to understand the physicality of the person who wore them. For me, it is an essential method of historical inquiry. Recently I recreated the missing components of a Tahitian chief mourner’s regalia (’ahu heva tūpāpa’u) now on permanent display at Perth Museum, Scotland and my encounter with Mai naturally led to me recreating the clothing he wore for Joshua Reynolds’s portrait (Fig. 3).[8] For this project, I have taken Reynolds’s depiction of Mai’s clothing as is. After having seen lots of majestic Tahitian clothing held in the stores of the British Museum, I believe the portrait is more or less realistic.

Kate Fullagar: I cannot wait to see the fruits of your recreations! Let’s turn now, though, to remembering Mai’s visit to Britain (1774–76). Jos Hackforth-Jones presented a paper on Mai’s popularity amid the context of Britain’s gentlemanly culture. Jos, why was Mai so popular among Londoners and what was his relationship to gentlemanliness?

Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones: Much of Mai’s celebrated status in London hinged on his ability to impress new acquaintances with his sensibility and good manners. Of particular interest is the radical nature of one of his performances, as a model gentleman, superior (according to Fanny Burney) to many contemporary English gentlemen.[9] Mai’s visual impact in this performance of politeness and sociability also enabled him to assume an identity acceptable to the English and secured him greater access to London “society.”

My focus on the European archive, namely the diaries of Fanny Burney, constitutes a partial lens and highlights the challenges of reading First Nations visitors via colonial texts, the uncertainly of this process and its speculative nature.

On first meeting Mai, Burney was overwhelmed by his ability to communicate gentlemanliness and politeness performatively “without words.”[10] This was unusual in the implication that this enactment was more to do with visuality rather than orality.[11] Given that Mai came from a culture steeped in ritual performances, it should not be surprising that he was quick to pick up and appropriate European visual codes. After noting that Mai was “very fine,” Burney continued: “. . . He makes remarkably good Bows—not for him, but for any body [sic], however long under a Dancing Master’s care.”[12]

Kate Fullagar: Dancing masters?

Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones: The role of dancing masters was integral to the performance of politeness and sociability.[13] In Lord Chesterfield’s recently published Letters, he had reminded his son to “take the best dancing-master . . . more to teach you to sit, stand, and walk gracefully, than to dance finely. The Graces, remember the Graces.”[14] Burney further extolled Mai’s recent appearance in a “new world” as if he had all his life “studied the Graces, [to] render his appearance and behavior politely easy and thoroughly well-bred.”[15]

Kate Fullagar: How do you think Londoners other than Frances Burney received Mai’s manners?

Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones: It was perhaps an irritation that this young man from Raʻiātea seemed to effortlessly master these “natural,” elite accomplishments. Mai may have felt some affinity with the stratification and rituals of London society since there were parallels with the hierarchical and ritualized nature of patrilineal Tahitian society.[16] He quickly picked up on the practice of imitating the best in society. I would speculate that this process began during the long voyage from Tahiti in the company of officers such as James Burney (Frances’s brother).

Arguably Mai was mimicking not just the gentlemanly codes of the colonizing society, but the very process of imitation itself, for his own ends—primarily to persuade George III (as seen in Fig. 4) to send him back to Tahiti with firearms. The added impact is also to undermine the very discourse of civility that defined this colonizing power.[17]

Certainly, the stage was set for Reynolds to take the unusual step of painting a full-scale grand style portrait of the Raiatean celebrity visitor.

Kate Fullagar: Fellow art historian Peter McNeil, in our workshop, was also attracted to the Burney archive on Mai, though he zeroed in on Mai’s gentlemanly dress. Peter, what insights into masculine dress did Mai’s presence in London generate?

Peter McNeil: Comparing a young courtier man at a gathering with Mai, Fanny Burney concluded in 1774 that the former was a “meer pedantic Booby . . . I think this shews how much more Nature can do without art, than art with all her refinement, unassisted by Nature.”[18] When Mai appeared at the English court wearing the requisite court clothing, he was certain to draw attention.

English viewers were alert to details of clothes not simply because they learned how to read a landscape thick with snobbery and social privilege, but because clothes carried a range of politically charged meanings. Mai was likely wearing a gifted set of “toys,” jewelry such as fobs, chains, snuffboxes and metal buttons, a sample of which were sent with him on his return voyage (almost certainly not children’s toys, as some have concluded).

Kate Fullagar: Tell us more about fashion in general in this time . . .

Peter McNeil: English design in all formats was changing rapidly at exactly the time Mai arrived in London. In England, there was a new premium on what was seen as “naturalness.” New types of spatial organization and interior decoration such as ungilded mahogany furniture (itself an exotic imported wood) found their corollary in dress. The taste for these fashions, which revealed more of the body’s natural outline, and the shift in both academic art and architectural circles and popular taste toward the neo-classical, resulted in new definitions of beauty. A broad-shouldered and slim-waisted type became favored as the male ideal. Male court dress moved its silhouette and cut from a focus on the horizontal, with stiffened wide skirts, to a closer fitting slim coat with short waistcoats and the side pleats eliminated.

Although George III wore rich dress for his men-only morning levees, as was customary, he had a personal dislike of extravagant dress. The new focus on an unencumbered and natural body, free of corsetry, make-up, and hair pomade, made the aristocratic courtier type appear debilitated, effete and old-fashioned. This is partly what Burney observed of Mai: he might have been wearing court dress, but he triggered a sense of the most up-to-date trends.

Burney’s comment also suggests the theme of distortion, of a departure from a norm based in “nature” or deviation from a natural given.

Reynolds’s choice to paint Mai either in white tapa, or a generic orientalizing but plain cloth, was thus highly charged and significant. Mai looked orderly and neo-classical in his tapa dress. Whether he appeared at court in European clothes (depicted in an engraving), or was painted famously by Reynolds, Mai was sure to attract fascinated attention.

Kate Fullagar: Monica Anke Hahn joined us all the way from Philadelphia. Monica, as you argued in Canberra, Pacific voyages produced not only a rich visual and written archive in eighteenth-century Britain but also “toys and games”—what were these and how do you assess their meaning today?

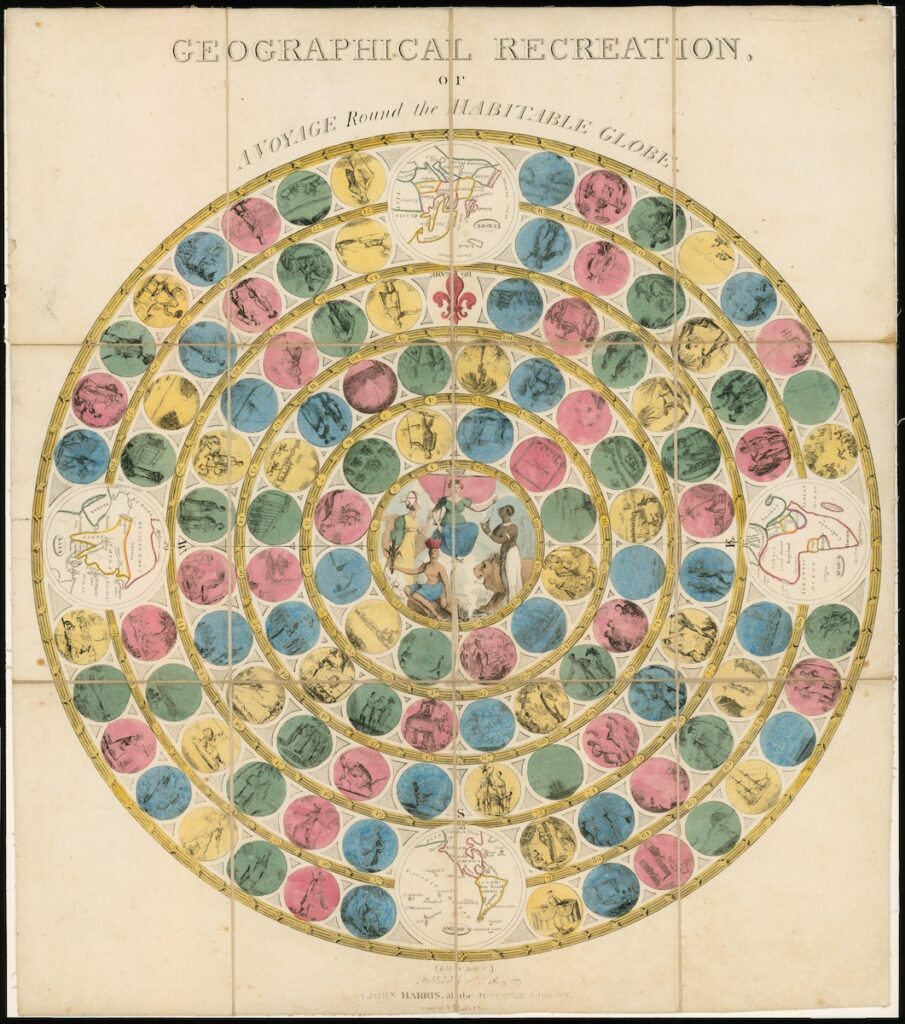

Monica Anke Hahn: Printed toys and games proliferated in Britain for the education of children—they were historical, scientific, and moral. Toys and board games with a geographic focus mirrored the expansion of British global colonial ambitions in the eighteenth century. Geographical Recreation; or a Voyage Round the Habitable Globe is a colorfully illustrated board game published by John Harris in London in 1809 (Fig. 5). Harris lifted the illustrations that mark areas of the Pacific directly from prints made by John Webber for the 1784 published account of Cook’s voyages. Webber was the shipboard artist on the third voyage, which returned Mai to Huahine after his two-year stay in England. Two or more players move their markers around the board’s four quadrants, each of which represents a distinct corner of the globe: Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Africa. A spin of a tetotum (a top with numbers on its faces) advances the player’s marker around the game board by continent—first Europe, followed by Asia, the Americas, and then Africa. The first player to return to Europe after this trip is the winner.

However, while the instructions of the game dictate that the players move through the world in numerical order, from Europe to Asia, and then North and South America to Africa, the consumer of the images playing the game might disrupt the voyage of discovery and occupation by moving out of turn, pursuing an unexpected journey. Just such a whirlwind journey took place in the stage production of the 1785 pantomime Omai, during which the titular hero used his subversive magical powers to traverse the globe before his installation on his Pacific throne. Objects like this game, with its performative potential allow—and I suggest even invite—rule breaking in order to discover the possibilities of subversion or transgression of the expected social order. The players of these toys and games can manipulate them according to their whims, their possibly subversive desires. These “scriptive” material objects (to borrow Robin Bernstein’s term) can disobey, resist, and destabilize expectations.[19] In this way, we might imagine their ability to illuminate the shortcomings, the moral flaws and the instability of the British social, cultural, and imperial order.

Kate Fullagar: What were some of the most important learnings from the workshop about Mai and Reynolds for you?

Monica Anke Hahn: Beginning with Peter Brunt’s brilliant keynote, “Turning British Art on Its Head,” I really valued the gestures toward Indigenous subjectivity and the networks of exchange between Britain and the Pacific made during the workshop. The agency in the visual representations of the people of Oceania comes into focus if we think past the relationship between Reynolds as “author” with Mai as “subject.” The focus on the Pacific world of Mai in our conversations subverts a more traditional art historical model and places Raʻiātea and its neighbors at the center and London at the periphery.

Kate Fullagar: Finally, let’s turn to Reynolds’s portrait itself. Carl Vail, an art historian resident in Canberra, argued in his presentation against some recent interpretations of it (including my own!). Carl, what are the main ways this portrait of Mai has been understood by scholars?

Carl Vail: Despite agreeing on its Tahitian subject matter, classical and oriental allusions, and Grand Manner style, scholars provide differing accounts of the painting’s meaning. For some, the portrait’s shared stylistic features with Reynolds’s portraits of European sitters evince a similar intention to ennoble Mai,[20] but for others the painting was a showcase of Reynolds’s skills.[21] Scholars have also sought to interpret the portrait by reference to Reynolds’s literary interests and Mai’s celebrity.[22] For most, the combination of details which individually appear to elevate or exoticize Mai, such as the prominence of his tattooed hands, complicates attempts to interpret the portrait.[23] This ambiguity has been attributed to Reynolds’s struggle to reconcile his universalizing principles of art with non-European subjects.[24] In its depiction of Mai’s cultural difference and geographical distance from European civilization, Reynolds’s portrait is often seen as representing Mai as a “noble savage.”

Kate Fullagar: Why do you think instead that “a coherent framework underlies the portrait”?

Carl Vail: My interpretation addresses the portrait’s presumed inconsistencies. The allusions in Reynolds’s portraits rely upon the viewer’s recognition to function.[25] This need for clarity argues against Mai’s portrait containing incoherent allusions. For eighteenth-century viewers, Mai’s loose robes and “turban” likely suggested not merely foreignness but “exotic aristocracy,” an association with classical precedents, but exemplified by Othello.[26] The allusion to Shakespeare’s play would explain the Venetian pictorial source for Mai’s pose and outfit, which recalls Paolo Veronese’s Aristotle (Fig. 6).[27] Reynolds knew this painting firsthand, which he also mentions in his Seventh Discourse.[28] In his portrait, Mai appears to reenact Act II scene I, when Othello, commander of the Venetian fleet, lands on the shores of Cyprus. The significance of this allusion is threefold. First, it heroizes Mai. This dignified portrayal aligns with laudatory descriptions of Mai’s character.[29] Secondly, it would have allayed imperialist concerns by representing Mai as a foreign subject loyally serving the empire’s interest abroad. Such concerns are believed to have prompted Reynolds’s efforts in the Seventh Discourse to accommodate non-Europeans within his aesthetic framework.[30] Thirdly, the self-referential nature of the pictorial source accords with the portrait’s likely function. It is thought that Reynolds created the painting as a showpiece for display in his studio. Reynolds conceived of his art in philosophical terms, evident in his Discourses and self-portraits.[31] Fittingly, in the portrait, Mai is not only posed as a philosopher but personifies philosophy through the union of Reynolds’s theory and practice.[32]

An Afterword From Our Keynote Speaker, Peter Brunt

Peter Brunt: Like Pauline, I too happened to be in London recently and took the opportunity to visit the National Portrait Gallery to see Reynolds’s painting of Mai for the first time. It was brilliantly installed, I thought, placed in the center of a red wall at the end of a long corridor, like the vanishing point in a Renaissance painting. To approach Mai, I passed smaller galleries on either side, hung with the portraits of Britain’s political and cultural icons of the modern era. In the end gallery, Mai was surrounded by important figures of the British eighteenth century, several of them painted by Reynolds as well: Joseph Banks, who accompanied Captain Cook on his first voyage, supported Mai’s desire to travel to “Beretane,” and more or less hosted him during his two years in England; John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, the prime minister who managed Britain’s contested colonial affairs in the 1760s; and others. The installation was nicely historicized. Yet after looking at Mai for some time, I couldn’t help thinking, “What was he doing there?”

A friend told me recently that Mai’s portrait had been exhibited in Aotearoa, New Zealand almost 50 years ago. It was shown at the old National Art Gallery in 1977, but few people saw it. Almost certainly no Māori, who were marginalized from the art institutions of New Zealand’s settler culture at the time, or migrant Pacific Islanders either, who didn’t have any presence in New Zealand’s art world then.

In my keynote lecture for the Canberra workshop, cheekily called “Turning British Art on Its Head,” I tried to address the workshop’s title — “British Art, Pacific Subjects, Contemporary Values”—by turning them around a bit. I invoked Bernard Smith’s classic book European Vision and the South Pacific to touch on the legacies of “British art” in the cultural histories of Australia and New Zealand.[33] I took “Pacific Subjects” to mean not the subject of Reynolds’s painting but the subjectivity of Mai—who was he, where exactly did he come from, how was his subjectivity shaped by the specificities of his culture and history, why was he in Britain making such a winning impression on everyone? “Contemporary values” reminded me of standing there in front of him in the National Portrait Gallery asking myself, “what is he doing there?” I asked: “What does Mai mean to us—to me, to Pauline, to Miriama Bono, who has also visited his portrait, to other Pacific Islanders, today?” It’s a question the British must ask themselves, as the painting is about to embark on a multi-stop tour of Britain before it departs for the J. Paul Getty Museum, its co-owner in Los Angeles.

After Miriama’s paper about a recent theatrical production in Tahiti about Mai, a side conversation developed about the possibility of the Reynolds painting being exhibited there. It seems to me at least a strong possibility. European museums and art galleries are already well advanced in “decolonizing” their collections and exhibition programs. Important treasures from Tahiti collected in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are, for the first time, on display at the Museum of Tahiti and The Islands, on long-term loan from The British Museum, the Musée du Quai Branly, and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge. I hope the painting is exhibited there, where I think we’d all like to see it.

Kate Fullagar is professor of history at the Australian Catholic University

Miriama Bono is the former director of the Museum of Tahiti and the Islands

Pauline Reynolds is a Pacific scholar, tapa-maker, and founding member of the Pacific ’Ahu Sistas Collective

Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones is an honorary professor and teaches art history at the University of Sydney

Peter McNeil is distinguished professor of design history at the University of Technology, Sydney

Monica Anke Hahn is assistant professor of art history at the Community College of Philadelphia

Carl Vail is an art historian and lawyer based in Kamberri/Canberra

Peter Brunt is associate professor of art history at Victoria University of Wellington

[1] “Joshua Reynolds’ Portrait of Mai Jointly Acquired by the National Portrait Gallery and Getty,” Getty, April 25, 2023, https://www.getty.edu/news/joshua-reynolds-portrait-of-mai-jointly-acquired-by-the-national-portrait-gallery-and-getty/.

[2] On the history of this work, see Kate Fullagar, “Reynolds’s New Masterpiece: From Experiment in Savagery to Icon of the Eighteenth Century,” Cultural & Social History 7, no. 2 (2010): 191–212. See also Sotheby’s lot 12 archive, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2001/important-british-and-irish-paintings-watercolors-and-drawings-l01183/lot.12.html.

[3] See Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), Export of Works of Art 2002-2003: Forty-Ninth Report of the Reviewing Committee (Stationery Office of the UK, 2003), 50; Stella Tillyard, “Paths of Glory” in Joshua Reynolds: The Creation of Celebrity, ed. Martin Postle (London: Tate Publishing, 2005), 69.

[4] R. Dashwood, director, “Portrait of Omai,” Imagine Documentaries, season 1, episode 6, aired July 23, 2003; DCMS, Export of Works of Art 2001-2002: Forty-Eighth Report of the Reviewing Committee (Stationery Office of the UK, 2002), 57.

[5] For Mai’s fuller history, see Kate Fullagar, The Warrior, the Voyager, and the Artist: Three Lives in an Age of Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), chapters 5, 7, and 8.

[6] Tupaia was a Raiatean priest who travelled on Cook’s first voyage. For recent work on him, see Khadija Von Zinnenburg Carroll, ed., Tupaia, Captain Cook and the Voyage of the Endeavour: A Material History (London: Bloomsbury, 2023).

[7] See Titaua Porcher-Wiart, Oh my! Omai (Tahiti: Au vent des îles, 2023).

[8] See Pauline Reynolds, “Reflections on Re/creating Missing Components of the ’Ahu Heva Tūpāpa’u for the Perth Museum (Scotland),” Journal of the Polynesian Society 133, no. 3 (2024): 325–336.

[9] Fanny Burney, The Early Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney, vol. II, 1774–7, ed. Lars E. Troide (Oxford: Clarendon, 1990).

[10] Burney, The Early Journals and Letters, vol. II, 1774–7, 60.

[11] See Lawrence Klein, Shaftesbury and the Culture of Politeness: Moral Discourse and Cultural Politics in Early Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

[12] Burney, The Early Journals and Letters, vol. II, 1774–7, 61.

[13] Michèle Cohen, Changing Pedagogies for Children in Eighteenth-Century England (London: Boydell Press, 2023), 121-149.

[14] Earl of Chesterfield, Letters to his Son, on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman 1737-1768 (London: Henry Frowde, 1774/1890).

[15] Burney, The Early Journals and Letters, vol. II, 1774–7, 63.

[16] Fullagar, The Warrior, the Voyager, and the Artist, 134.

[17] See Jos Hackforth-Jones, “Mai/Omai in London and the South Pacific,” in Material Identities, ed. Joanna Sofaer (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007), 13-30.

[18] Burney, The Early Journals and Letters, vol. II, 1774–7, 63.

[19] Robin Bernstein, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: NYU Press, 2011), 12–14.

[20] The National Portrait Gallery London describes the painting as “the first British portrait to represent a person of colour with grandeur, dignity and authority.” “Mai (Omai),” National Portrait Gallery, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw304993/Mai-Omai, accessed June 2025.

[21] Mark Hallett, Reynolds: Portraiture in Action (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 425–26, and Bernard Smith, Imagining the Pacific: In the Wake of the Cook Voyages (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 176–78.

[22] Douglas Fordham, British Art and the Seven Years’ War: Allegiance and Autonomy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 194–200; Stuart Sillars, “Race and Rank in Othello” in Shakespeare Seen: Image, Performance, and Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 205–230; Martin Postle, ed., Joshua Reynolds: The Creation of Celebrity (London: Tate Publishing, 2005).

[23] Martin Postle, Sir Joshua Reynolds: The Subject Pictures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Harriet Guest, “Curiously Marked: Tattooing and Gender Difference in Eighteenth-century British Perceptions of the South Pacific,” in Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History, ed. Jane Caplan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 83–101.

[24] Postle, Sir Joshua Reynolds, 218; Guest, “Curiously Marked,” 83–101; Fullagar, The Warrior, The Voyager, and the Artist, 215.

[25] Stuart Sillars, Painting Shakespeare: The Artist as Critic, 1720-1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 195. See also Postle, Sir Joshua Reynolds, 5.

[26] See Bernard de Montfaucon, Antiquity Explained and Represented in Sculpture, trans. David Humphrey, vol. III (London: J. Tonson and J. Watts, 1722), 8–9; Sillars, “Race and Rank in Othello”, 217–22.

[27] Not only is Othello a Venetian general, but in Act II, scene I, his lieutenant Cassio arrives in Cyprus on a Veronese ship, “A Veronesso” in [John] Bell’s Edition of Shakespeare’s Plays, vol. 1 (London:1774/ London: Cornmarket Press, 1969), 173.

[28] See Reynolds’s sketchbook, British Museum, acc. no. 1859,0514.304, and Robert R. Wark ed., Sir Joshua Reynolds Discourses on Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 141.

[29] Hackforth-Jones, “Mai/Omai in London and the South Pacific,” 13–31.

[30] Fordham, British Art and the Seven Years’ War, 194; Fullagar, The Warrior, The Voyager, and the Artist.

[31] See John Barrell, The Political Theory of Painting from Reynolds to Hazlitt: “The Body of the Public” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 85–87; Wark, Sir Joshua Reynolds Discourses on Art, 50.

[32] Cesare Ripa, Iconologia or Moral Emblems. Newly Design’d, and Engraved on Copper by I. Fuller, (London: Benjamin Motte, 1709), 31.

[33] Bernard Smith, European Vision and the South Pacific (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1960).

Cite this note as: Kate Fullagar, Miriama Bono, Pauline Reynolds, Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones, Peter McNeil, Monica Anke Hahn, Carl Vail, Peter Brunt, “Reflections on Mai, Joshua Reynolds, and Eighteenth-Century Art—A Rountable,” Journal18 (June 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7899.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.