To welcome visitors, the exhibition Colonial Crossings: Art, Identity, and Belief in the Spanish Americas (July-December 2024) created a large-scale map illustrating transoceanic routes across the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. This map highlighted one of the many meanings of “crossing” as a voyage across water. As the exhibition vividly illustrated, the act of crossing gains additional significance from the colonial (dis)order’s movement across water. The expansion of European sociocultural norms unfolded not only through official maritime expeditions but also through the voluntary and involuntary displacement of people, objects, artistic styles, and precious materials. These circulations shaped complex ideologies of religion, race, and status (Fig. 1).

This map served as a central feature of the first large-scale exhibition of colonial Latin American art at Cornell’s Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, guiding audiences through the colonial world of empires, mercantilism, and oceanic encounters and invasions. Covering 300 years of colonial history, the exhibition was curated by Dr. Andrew Weislogel, Curator of European Art before 1800, Dr. Ananda Cohen-Aponte, Associate Professor of History of Art at Cornell, and undergraduate and graduate students (Osiel Aldaba, Miguel Barrera, Daniel Dixon, Juliana Fagua Arias, Miche Flores, Isa Goico, Sara Handerhan, Emily Hernandez, Ashley Koca, Maximilian Leston, Maria Mendoza Blanco, Lena Sow and Nicholas Vega). The show looked across regions to explore the artistic connections created by artists of different socioracial backgrounds residing in the Spanish Americas. Displayed works were drawn from the collections of the Johnson Museum of Art and Cornell Libraries, the Denver Art Museum, and the Hispanic Society of America, with the majority on loan from the Carl and Marilynn Thoma Foundation, one of the largest private collections of colonial Latin American art in the U.S., with exhibition spaces in Santa Fe and Dallas.

From the entrance, the exhibition was organized into seven thematic sections: Key Religious Figures in Colonial Latin American Art, Ex Votos and Material Histories, The Virgin Mary: Holy Mother and Queen, Asia in the Americas, Prints and Power, The Social Fabric of Colonial Latin America, and Landscape, Place-Making, and Local Knowledge. These sections were housed within a large gallery divided into three distinct spaces. The first space focused primarily on Marian devotion, guiding visitors through religious artworks from Peru, Mexico, and Bolivia that depicted the Virgin Mary in her regional forms. These works formed part of the exhibition’s narrative of traditions and revealed the syncretism of Indigenous and Afrodescendant peoples through depictions of visual materials, festivities, and regional stories. This curational approach allowed viewers to make connections between political and religious ideas simultaneously.

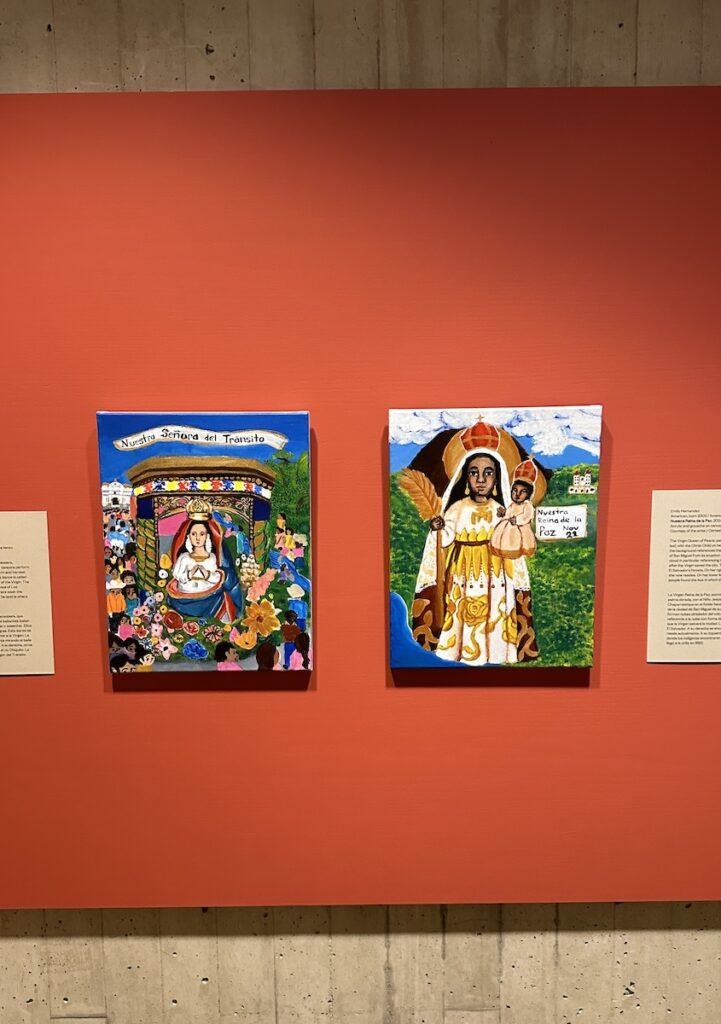

For example, depictions of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico and the Virgin of Cocharcas in Bolivia reflected both the devotion and peregrination of the Americas’ populations, as well as the colonial authorities’ imposition of this devotion on Indigenous peoples to serve political agendas. Additionally, as noted on the wall label, the representation of the Virgin of Guadalupe from Extremadura, Spain—a Black Madonna—was transformed into a brown-skinned depiction in Bolivia, which raised questions about racial transformation and its role in appealing to the Andean population during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This section of the exhibition also paired depictions of the Virgin Mary with contemporary and pre-Columbian works from the Johnson Museum of Art’s collection (Fig. 2). These pieces effectively connected the themes of womanhood and motherhood across time and presented the exhibition as a convergence of different periods, styles, and mediums. It also served as a bridge between visual and literary works, such as the Manifiesto Satisfactorio Anunciado en la Gaceta de México (1790) from the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at Cornell University.

As viewers moved to the middle part of the of the exhibition, the artworks showcased a variety of colonial scenes that spanned space and time, highlighting issues of discrimination and racism within the Spanish Americas. From an eighteenth-century casta painting, De Xibano y Española, produce Tornatras (Xibano and Spaniard Produce Tornatras), to the depiction of Saint James as Santiago Mataindios (Saint James, Slayer of Indians) or Santiago Mataincas (Slayer of Incas) in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Peru, visitors could learn about the intersections and exchanges of racialization ideologies between Europe and the Americas (Figs. 3 and 4). Though made predominantly in colonial Mexico, casta paintings often traveled to Europe, where they emphasized racialized traits and legitimized the marginalization of the “Other” abroad. These works functioned as tools to reinforce the hierarchies of colonial society, further enabling extractivist and violent European practices.[1] Furthermore, while Saint James is depicted here imposing norms, mistreating, and even killing Indigenous peoples, as the wall label asserted, this ideological form of Saint James was subsequently transformed and transferred through syncretic practices by many Andean Indigenous communities into “Christian huacas” as a figure of religious admiration.[2]

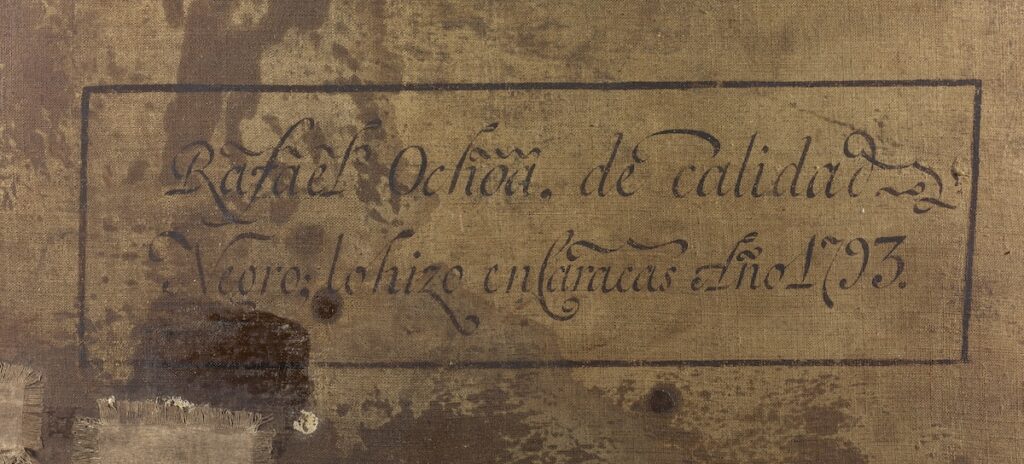

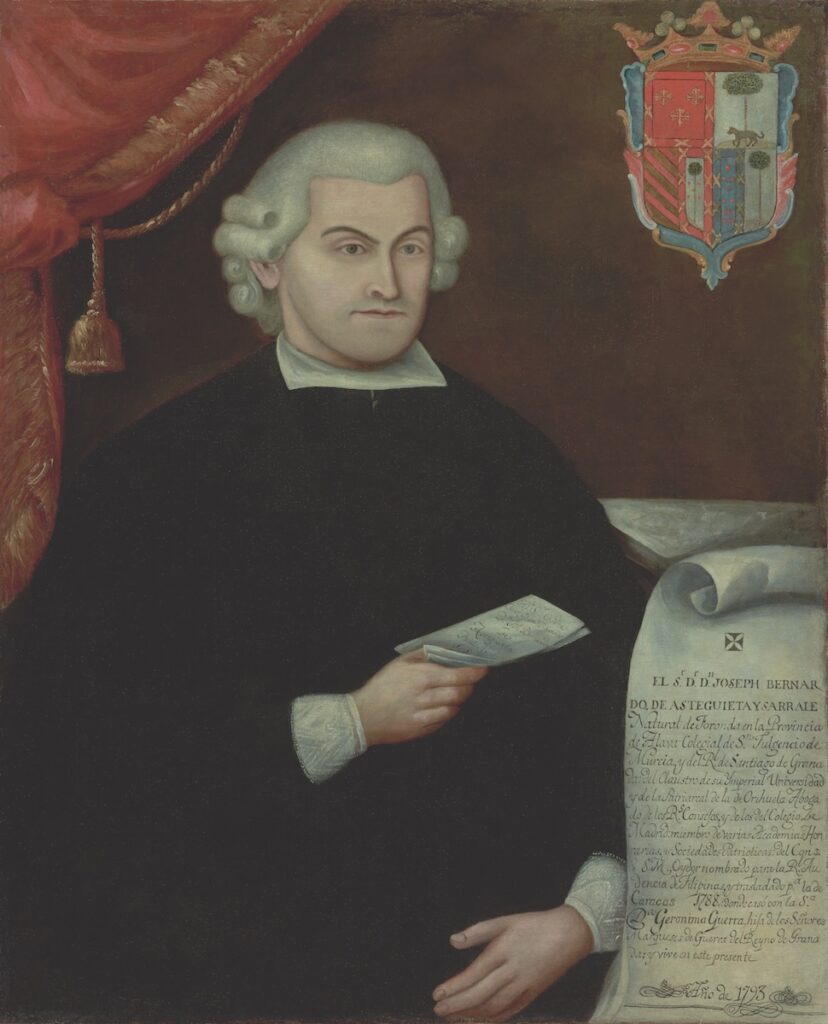

Central to the exhibition was an emphasis on the crucial, but often overlooked, role of racialized individuals in the history of art, particularly in art’s creation and distribution. In the middle section of this part of the show, visitors encountered the portrait of Don José Bernardo de Asteguieta y Díaz de Sarralde (1793), a typical portrayal of a colonial official residing in Venezuela (Fig. 5). However, this artwork was displayed both front and back, revealing that the painter, Rafael Ochoa, signed his name as a Black artist, explicitly identifying himself as “de calidad negro” (“of Black status”) (Fig. 6). This unique signature provides a rare glimpse into an Afrodescendant artist asserting his Black identity in colonial Venezuela. Throughout the exhibition, numerous connections were made between racial discourses and colonial Latin American traditions, as well as the materials used in the artworks, including Prussian blue, orpiment, and carmine/cochineal, whose samples and applications were also on display. Together, these elements, and the ways they were depicted and arranged in the exhibition room, provided a profound exploration of the global exchanges of ideas, materials, labor, and people—whether they participated voluntarily or were forced to contribute—to the formation of colonial Latin America.

As visitors moved to the final section of the exhibition, they encountered a unique and central piece of furniture that allowed the audience to appreciate the global exchange of artistic styles and materials. This remarkable writing cabinet, crafted from Mexican lacquered and polychromed wood with intricate painted decorations by José Manuel de la Cerda—one of the few recognized Indigenous artists in colonial Latin America—illustrated the peak of this fusion. Active in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, Mexico, de la Cerda drew inspiration for his work, including this exquisite piece, from the artistic influences that arrived in Mexico from Europe and Asia via Spain’s vast trading networks. In this cabinet, one could observe the influence of Chinese lacquer through detailed landscapes teeming with flora, fauna, and architectural forms from across the globe.[3]

The concept of “crossing” also applied to the curatorial process of this exhibition, in which faculty members and curators collaborated with undergraduate and graduate students from Cornell University. The exhibition proved unique not only for introducing colonial Latin American art thematically to central New York, but also for centering students in the curatorial process. As the outcome of Dr. Cohen-Aponte’s semester-long course Colonial Connectivities: Curating the Arts of the Spanish Americas (ARTH 4166/6166), the exhibition gave students the chance to participate directly in the often-rarefied curatorial process, allowing them to select artworks and write object labels and wall text. In fact, it was the students who developed the specific themes at the end of the course after having researched the artworks and planned the logistics for the exhibition.[4]

Another notable feature of the exhibition was its pairing of colonial-era pieces with contemporary artworks created by an undergraduate student, Emily Hernandez (Class of 2025), a Salvadoran-American Fine Arts major at Cornell whose paintings Nuestra Señora del Tránsito and Nuestra Reina de la Paz were featured in the exhibition’s final section (Fig. 7). When Hernandez noticed the absence of Central American art in the collection, she secured funding to travel to El Salvador, where she studied traditions that continue from the colonial legacy of the eighteenth century. Drawing from her research, she created these two paintings, which were displayed within the exhibition’s broader context.[5]

Colonial Crossings engaged in dialogue with previous exhibitions that paired colonial Latin American art with contemporary works.[6] Its true innovation, however, lay in its pedagogical approach, offering a compelling example of how to bridge the classroom and the museum. By connecting fine art students’ creations with works produced in Latin America between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, it fostered a meaningful “crossing” of time and context. Despite covering diverse regions, time periods, and themes, the collaboration between curators and students ensured that the exhibition remained clear and accessible, offering educational value to all—from field experts to those just beginning to learn about colonial Latin American art.

Juan Manuel Ramírez Velázquez is Assistant Professor of Spanish and Colonial Latin American Literatures at Colgate University, NY

[1] Magali M. Carrera, Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings (University of Texas Press, 2003), 49.

[2] Iris Gareis, “Andean Gods and Catholic Saints: Indigenous and Catholic Intercultural Encounters,” in The Andean World, ed. Linda J. Seligmann and Kathleen S. Fine-Dare (Routledge, 2019), 273.

[3] See Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia, temporary exhibition, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, August 18, 2015–February 15, 2016, and its exhibition catalogue: Dennis Carr et al., Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia (MFA Publications, 2015), with a cover image fragment of the cabinet.

[4] From an email exchange with Ananda Cohen-Aponte on January 16, 2025.

[5] From an informal conversation with Emily Hernandez on September 29, 2024.

[6] See, for example, La palabra es de plata, el silencio de oro, temporary exhibition, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, June 8, 2022–June 18, 2023; ReVisión: Art in the Americas, temporary exhibition, Denver Art Museum, October 24, 2021–July 17, 2022; El Dorado: Myths of Gold, temporary exhibition, Americas Society, New York City, September 6, 2023–May 18, 2024.

Cite this note as: Juan Manuel Ramírez Velázquez, “Colonial Crossings: A Review” Journal18 (May 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7880.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.