Shilpa Shah and Rosemary Crill, The Shoemaker’s Stitch: Mochi Embroideries of Gujarat in the TAPI Collection (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2022). 220 pages. ISBN 9789391125455.

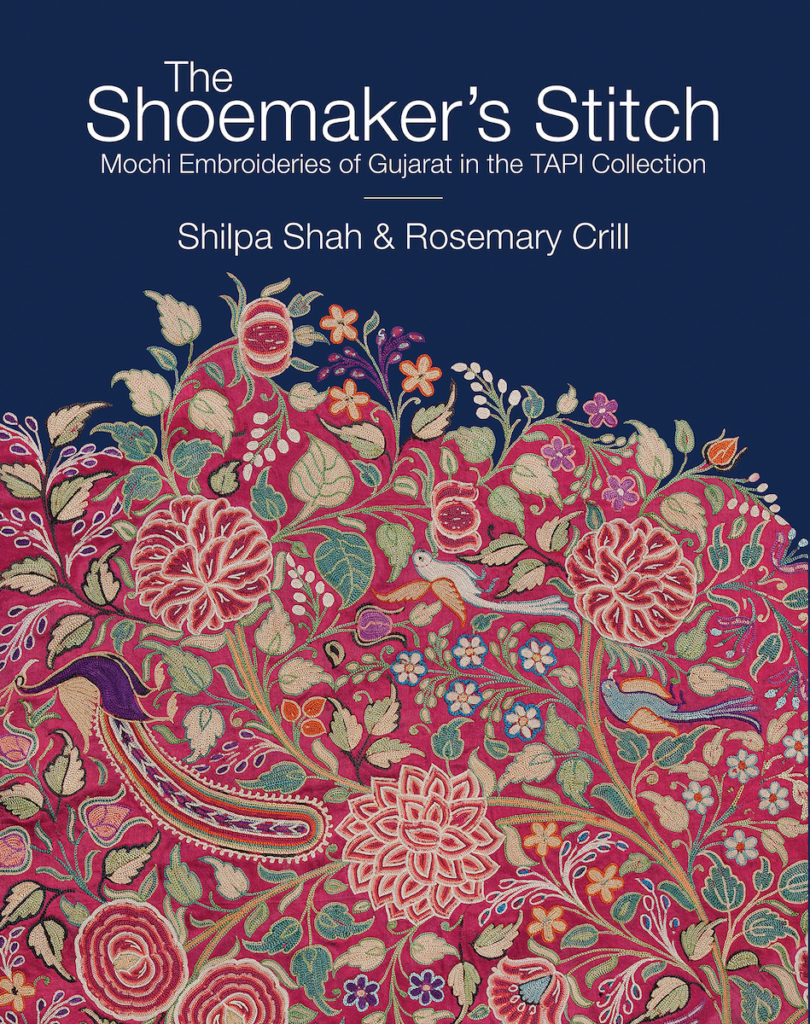

The detailed image of chain-stitch embroidery that wraps around the cover of The Shoemaker’s Stitch hints at the attention to technique and creative process that pervades the volume. Throughout The Shoemaker’s Stitch, co-authors Shilpa Shah, a scholar and collector, and Rosemary Crill, former Senior Curator for South Asia at the Victoria & Albert Museum, link their textile expertise with a humane approach that both engages the tactile qualities of the shining embroideries and works to recover the history of the Mochi (shoemaker) community and their professional sphere of kaarigars (literally “skilled makers,” often translated as “artisans”).

The rich catalogue provides visual access to the TAPI Collection, co-founded by Shilpa and Praful Shah in Surat, India, in the 1980s.[1] The volume contains stunning, detailed images of such diverse objects as floor spreads for Mughal courts, eighteenth-century dress fabrics exported to Europe, and wall-hangings for contemporary homes in Gujarat, all of which are linked by the shared form of chain-stitch embroidery. While some of these objects have been featured in other volumes on the textiles of South Asia, The Shoemaker’s Stitch is the first to focus solely on the relationship between the Mochi community in Kutch and chain-stitch embroidery in South Asia more broadly.[2] The authors place the objects in this broader context by compiling popular myths and oral accounts, recording the names of individual embroiderers, engaging active community members, and documenting ephemeral business records and design sketches. The result is an expansive study that both deepens and broadens the pathways for understanding the lived and living history of this dynamic form of needlework. As Shah and Crill demonstrate, the chain-stitch embroidery known as mochi-bharat (Mochi embroidery) has been at once regionally specific and far-reaching, with a historic presence outside the Mochi community and a dynamic legacy in the work of contemporary makers.

In Gujarat, and particularly in Kutch, elaborate multicolor embroideries worked entirely in silk chain stitch have traditionally been produced by the Mochi community of leatherworkers and shoemakers. While surprising, the connection between silk embroidery and shoemaking is significant because the needle used for the embroideries (an aari) was adapted from a cobbler’s awl (aar) and ends in a small hook (Fig. 1). The key benefit of aari embroidery is that it allows for a much faster, more streamlined chain-stitching process than that of a straight needle.[3] The motion required to create the series of interlinking teardrop-shaped loops of the chain propels the embroidery forward, lending itself to meandering outlines and concentrically filled curvilinear shapes that often end in tapered points echoing the form of individual stitches (Fig. 2).

Although it is unknown how exactly Gujarat came to be a center for aari work, the general consensus is that the chain-stitch technique stems from leather embroiderers in Sindh, an area in present-day Pakistan with strong historical links to Gujarat across the Thar Desert.[4] Among the various originary accounts included in The Shoemaker’s Stitch, one locates the transfer of knowledge from Sindhi to Kutchi kaarigars in the eighteenth century during the reign of Maharao Deshalji of Kutch (r. 1718-1741). When Sindhi embroiderers were commissioned to work on the royal tents for the court of Kutch, the Maharao recognized an opportunity to cultivate this desirable new skill in his kingdom. Under royal direction, the Kutchi kaarigars spied upon the embroiderers through peepholes in the tent cloth until “they dispossessed the Sindhis of their art” (28). Other stories locate the introduction of Sindhi stitching techniques to Kutch much earlier, as far back as the fourteenth century. Shah and Crill’s inclusion of these multiple accounts productively reminds the reader of the pre-Partition connections between the traditions of chain-stitch embroidery in Gujarat, India, and Sindh, Pakistan, while also making room for the manifold nature of historical origins.

The earliest surviving examples of Gujarati chain-stitch embroidery currently known are the rare and celebrated pieces made for the Mughal and Rajput courts in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[5] More plentiful are extant pieces made for export to Europe in the first half of the eighteenth century. Large repositories exist in institutions such as the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[6] Together the two categories comprise what have long been seen as the finest examples of the tradition, with the disproportionate preservation of exports to Europe creating an emphasis on pieces tailored to the European market. In her coverage of this period, Crill expands upon a recent finding that holds significance for the attribution of these prestigious textiles to the Mochi community: all of the seventeenth and eighteenth-century pieces in the TAPI Collection were worked with a straight needle.[7] The process for determining the type of needle used typically requires seeing the back of the work, where one can determine whether a continuous line of stitches has been created by the hooked aari needle, or whether slight gaps have been left by the straight needle.

Through descriptions of the visual cues one should look for and illustrative photographs, Crill provides practical instructions for analysis that will prove useful for researchers (Figs. 2 & 3). The identification of the use of a straight needle for the earlier works could either cast doubt on the narrative that Mochi embroidery evolved from the use of the cobbler’s awl or, as proposed by Crill, shed new light on the appeal of the art form (10). Crill suggests that the early Mughal textiles may have been emulations of the effect of the “shoemaker’s stitch” by embroiderers working at the royal Mughal karkhanas (workshops) who were not themselves members of the leatherworking Mochi community, and therefore did not use the characteristic aari, but recognized the visual appeal of this dense and luminous silk embroidery technique.

Past studies of Gujarati chain-stitch embroidery have reinforced a historiographical gap that separates pieces made for the Mughal court and for export to Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries from those made for the domestic market in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a separation that has long prevented comparative studies across the full corpus of embroidered textiles from South Asia.[8] That Shah and Crill include eighteenth-century examples worked with a straight needle and contemporary aari work by non-Mochi artisans in the catalogue suggests that the “shoemaker’s stitch” is a more fluid designation than the technical and ethnographic parameters of the book’s title imply. The maker does not need to be of the Mochi community nor use a cobbler’s awl for their work to be tied to the tradition. In this way, The Shoemaker’s Stitch broadens the signature chain-stitch embroidery of the Mochi community into an art form that encompasses both the community’s own work and the impact of their technique on embroidery throughout South Asia.

If The Shoemaker’s Stitch illustrates nineteenth-century furnishings and items of dress made for the domestic market (Fig. 4), it also augments the published corpus of Mochi embroidery potentially made earlier. Dado panels made for the royal palace at Bhuj, the capital of Kutch, may date from the time of its building in approximately 1740 and are firmly attributed to local Mochi embroiderers (Fig. 5). A set of cushions and knuckle covers that entered the Jaipur royal collections by 1770 were likely made by Mochi embroiderers and may have been made for a royal wedding in 1730 (12, 26). Together with a rare intact and fully embroidered ceremonial tent made for the ruler of the principality of Dhrangadhra in Gujarat in 1856, the publication of these pieces created for Gujarati and Rajput royalty sheds new light on the role of Gujarati chain-stitch embroidery within South Asia, and not just Europe, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

After three chapters on the technical features and geographic diffusion of chain-stitch embroidery, the history of the Mochi community, and the “afterlife” of their work, The Shoemaker’s Stitch provides a catalogue of chain-stitch embroidered objects in the TAPI Collection from the eighteenth-century to the present day. The catalogue is divided into “Mughal Embroideries,” “Embroideries Traded to Europe,” “Garments,” “Embroideries for the Gods,” “Jain Manuscript Covers,” “Furnishings,” and “Contemporary Chain-stitch Embroideries by Non-Mochi Artisans,” with nineteenth- and twentieth-century garments comprising the largest section. The textile expertise of the authors is reflected in the captions, which name not only the garment types, but also the cloth used as the ground for the embroideries, such as gaji satin or silk-and-cotton mashru. The captions also identify whether the chain stitch was worked with a straight or hooked needle, making the catalogue especially useful for textile scholars who might not otherwise have access to the back of the cloth.

The Shoemaker’s Stitch also makes valuable contributions to the study of the cultural history of Kutch. In an appendix following the catalogue, the authors publish a list of the prominent kaarigars from Kutch from around 1880 to the present day, including Mochi embroiderers, leatherworkers, and shoemakers along with silverworkers and enamel inlay artists of various backgrounds (204-10). The record provides more than just names and dates wherever possible, even attributing specific works to some of the kaarigars. A second appendix contains a newly compiled record of women Mochi embroiderers of Kutch in the twentieth century (211). The list and the accompanying information on vanshparampara—the practice of women meeting aari-work orders from their homes to supplement the family income—is an invaluable contribution to the study of Mochi embroidery and its makers. Although this data on twentieth-century modes of production cannot be simply projected onto earlier time periods, it cautions us to question the commonly applied historical assumption that embroidery determined to be of professional quality points to a male maker.

In the preface, Shah and Crill write that the Shoemaker’s Stitch is meant to pay tribute to the unnamed and forgotten kaarigars of this stitch craft by drawing attention to the exquisiteness of their production. In the end they have gone further, recovering the names of many individuals and families for the public record and beginning to chart their legacy through the work of contemporary artists.

Katy Rosenthal is a Ph.D. student in History of Art at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania

[1] The Shoemaker’s Stitch is one of many publications focusing on the TAPI (“The Art and People of India”) Collection, the most recent being Jeremiah Losty, Court & Courtship: Indian Miniatures in the TAPI Collection (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2020). Like The Shoemaker’s Stitch, Shilpa Shah and Tulsi Vatsal, Peonies & Pagodas: Embroidered Parsi Textiles: TAPI Collection (Surat: Garden Silk Mills, 2010) was also the first book dedicated solely to this form of embroidery. Rosemary Crill contributed to Ruth Barnes, Steven Cohen, and Rosemary Crill, Trade, Temple & Court: Indian Textiles from the TAPI Collection (Surat: Garden Silk Mills Limited, 2002); and Steven Cohen et al., Kashmir Shawls: The Tapi Collection (Mumbai: Shoestring Publisher, 2012).

[2] Recent volumes on textiles of South Asia which feature chain-stitch embroideries from Gujarat include Rosemary Crill et al., Indian Textiles: 1,000 Years of Art and Design (Washington, D.C.: The George Washington University Museum, 2021); and Avalon Fotheringham, The Indian Textile Sourcebook: Patterns and Techniques (London: Thames & Hudson, 2019).

[3] The Victoria & Albert Museum produced a video for the 2015 exhibition The Fabric of India that shows footage of contemporary aari embroidery at the Sankalan embroidery design and production house in Jaipur, Rajasthan, and gives a greater sense of the historical technique. Victoria & Albert Museum, “How was it Made? Ari Embroidery,” September 30, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbyE1JEJug0.

[4] On the embroidery traditions of Sindh, see Nasreen Askari and Rosemary Crill, Colours of the Indus: Costume and Textiles of Pakistan (London: Merrell Holberton Publishers, 1997), 15-63. For the historical ties of Gujarati embroidery traditions to those of Sindh, see Eiluned Edwards, Textiles and Dress of Gujarat (London: V&A Publishing, 2011), 154, 161; and Willem Vogelsang and Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, eds., Encyclopedia of Embroidery from Central Asia, the Iranian Plateau and The Indian Subcontinent (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), 314. For trade across the Thar Desert, see Tanuja Kothiyal, Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

[5] For example, a c.1620-30 riding coat made for a member of the Mughal court held in the Victoria & Albert Museum (accession no. IS.18-1947) has been published extensively, including by Crill in Rosemary Crill, ed., The Fabric of India (London: V&A Publishing, 2015), 108-09; a c.1640-50 hanging embroidered for use in the Mughal court pictured on p. 13 of The Shoemaker’s Stitch (V&A IS.168-1950) has a similar list of bibliographic references. Rahul Jain has published on textiles embroidered for the Rajput court, including the fully intact “Lal Dera” tent at Mehrangarh Fort in Jodhpur, which Crill notes in the Shoemaker’s Stitch, 32. See Jain, Durbar: Royal Textiles of Jodhpur (Jodhpur: Mehrangarh Museum Trust, 2009), 124-29.

[6] For more on eighteenth-century Gujarati chain-stitch embroideries exported to Europe, see Crill, “Textiles for the Trade with Europe,” in Barnes, Cohen, and Crill, Trade, Temple & Court, 101-02; and Melinda Watt, no. 74, and Amelia Peck, no. 75, in Peck, ed., Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), 230-34.

[7] Crill notes that this finding aligns with recent technical examination of the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection, as discussed in Fotheringham, The Indian Textile Sourcebook, 33.

[8] This categorization was put forth in John Irwin’s influential work on embroideries held in the Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad, which discusses Gujarati chain-stitch embroideries from the sixteenth to the early eighteenth century under the chapter “Trade Embroideries of the 17th and 18th Centuries,” and nineteenth- to early twentieth-century “Mochi Embroideries of Bhuj” under the chapter “Regional Styles: Kutch.” Irwin and Margaret Hall, Indian Embroideries (Ahmedabad: Calico Museum of Textiles, 1973), 29-34, 73-80.

Cite this note as: Katy Rosenthal, “The Shoemaker’s Stitch: A Review,” Journal18 (March 2023), https://www.journal18.org/6737.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.