In his room-sized watercolor work Room for a Lost Paradise, Robert Horvath evokes some signature stylistic moves of the rococo: ornate elegance, a sensuous palette, and an emphasis on playful intimacy. But beyond those aesthetic affinities, in its making, the work also deploys technology in ways that remind us how repetition and reproducibility defined the rococo. In this way, Horvath’s method shows us the intersection between the historical style of the rococo and an emergent logic of technological reproduction that destabilized traditional notions of originality at the time—a logic that, through Horvath’s work, continues to challenge us today.

Horvath’s immersive room-painting, which visitors may physically enter, sits within the larger exhibition space at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. The installation consists of four walls, a floor, and a ceiling, each surface covered with hand-painted watercolor elements that mimic the appearance of an interior room of a French aristocratic home of the eighteenth century. In the work’s painted surfaces, the artist painstakingly recreates in watercolor all the decorative elements one might expect in such an interior: boiseries (carved wood paneling), ornate gilding, geometric parquet flooring. To enter the work is to be overwhelmed by the sheer audacity of Horvath’s project and its abundance of marvelous, hand-painted detail. In its gosh-wow technical brilliance, the work elicits feelings of awe and wonder, and a traditional aura of artistic originality suffuses the work’s presence. To that contemporary shorthand question of artistic skill, “could my kid do this?”, the answer is, resoundingly, no.

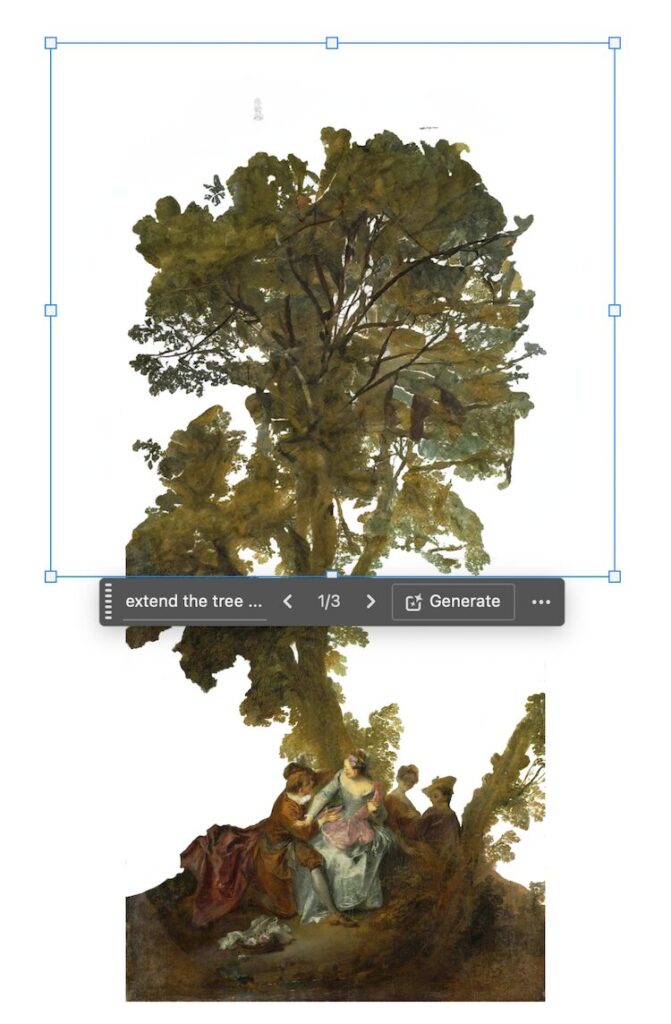

And yet, as you move through the work and learn of its making, that aura begins to dissipate. On the walls, four inset painted panels depict typical subjects for this historical period: two images of Venice in the style of Canaletto, and two larger scenes that borrow from celebrated fêtes galantes by Watteau and Lancret. In remaking them, Horvath altered these images from their sources. For the fêtes galantes, he created digital sketches using generative AI tools to augment the source image. For example, to make Watteau’s Cythera fit the vertical format of the right painted panel on the right wall, Horvath needed to extend the form of the tree that anchors the composition on the right. To accomplish this formal exercise, he used the Generative Fill feature of Photoshop, uploading an image of the original painting and repeatedly prompting the tool to extrapolate and extend the tree’s form within the space of the image (Fig. 1). Working from that digital sketch, Horvath then painted the final image in watercolor on prepared paper mounted to panel. In creating different parts of the room, the artist moved fluidly between the handmade and the digital in his practice, using digital collage and iPad drawing alongside freehand sketching.

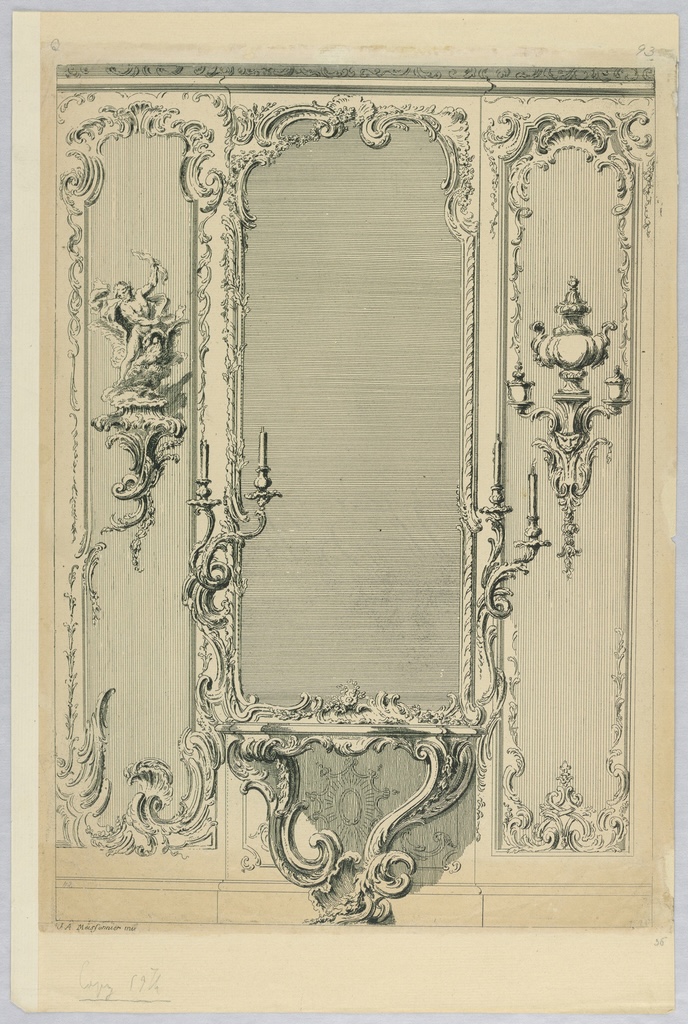

While generative AI might seem a world away from the hand-carved boiseries of Parisian hôtels particuliers, in fact Horvath’s use of digital tools conceptually aligns with the rococo’s relationship to originality and the copy. In the eighteenth century, the concept of originality was diffuse, especially in the decorative arts, where authorship was often collective or anonymous. Repetition and reproduction were valorized: for example, decorative pattern books by artists like Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier codified the rococo style into portable and repeatable templates, disseminating a visual vocabulary to use in designing interiors. Far from undermining the appreciation of the designs they reproduced, Meissonnier’s pattern books and engravings in fact enhanced the prestige of those designs by framing them as models to emulate—and to then embellish.

In his overall designs for Room for a Lost Paradise, Horvath did just that, using images of Meissonier engravings such as Design for a Console and Mirror (Fig. 2) as the basis for his painted panels. In these pattern books and engravings, the ornamental language of the rococo—its shells, swirls, crests, and vines—presupposed repetition and variation. Rococo patrons who commissioned these decorative interiors for their gilded mansions valued the skill with which a design was deployed more than its status as an “original” artwork. You can trace such a logic in other modes of historical rococo decorative production as well, as in the serial-yet-refined porcelain objects made at the French royal manufactory at Sèvres, or in the luxury textiles block-printed in Lyon. Each of these embrace emergent technologies of reproduction yet privilege a high degree of skill in the finish to convey a sense of refined luxury and handmade virtuosity.

We might view Horvath’s use of digital tools in a parallel way: not as a shortcut that diminishes artistic value, but as a contemporary extension of the rococo’s long-standing entanglement with replication, variation, and mediated authorship. Just as eighteenth-century artisans used engraving plates and pattern books to generate decorative forms that were at once repeatable and luxurious, Horvath uses generative AI and digital collage to activate new possibilities within a historically rich aesthetic language. His work challenges us to reconsider where originality resides—not in the singular gesture or untouched source, but in the layered act of translation, from past to present, from algorithm to image, from digital sketch to painted surface. In this light, Room for a Lost Paradise does more than revive rococo ornament—it reanimates its logic, offering a compelling meditation on the ongoing dialogue between craft, technology, and artistic authorship.

Chad Alligood, an independent curator and art historian focusing on historical and contemporary American art, is Board President at Voices in Contemporary Art (VoCA)

Cite this note as: Chad Alligood, “Ornament and Algorithm” Journal18 (July 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7920.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.