The place without worry, Sanssouci, is a space of pseudo-domestic decadence. A place set apart from his court, King Frederick II of Prussia’s “Weinberghäuschen (little vineyard house)” was meant to be a space of repose. But, for all its gilded vines and cascades of flowers—the pastel rusticity of its decorative panels, its corpulent putti floating overhead, its herons and monkeys and parrots stepping out from the walls—for all their whimsy and lightheartedness, they could not break the villa away from its earthly moorings. For all the artists, craftspeople, and musicians hired to soothe the nerves of their warlord Frederick, he and his entourage were grounded in their material world. The smells from the chamber pots, the sweat-mixed perfume of attendants and overdressed aristocrats, the manure fertilizing the gardens no doubt wafted through the halls on sticky-hot summer days. Art could not hide the scents and scenes of this decay-entangled decadence.

Robert Horvath’s Room for the Lost Paradise does not conjure the olfactory assaults of eighteenth-century Sanssouci. An uninhabited block in a twenty-first-century art gallery, it lacks a procession of elites in silks and translucent lace. Its seeming laser cut precision suggests none of the bodily realities of the rococo. Nevertheless, like its eighteenth-century rococo predecessors, it conveys both the decay and decadence of the society in which it lives. While rococo fantasies such as Sanssouci fervently attempt to hide behind a facade of apart-ness, of un-worry, of fleeting pleasures, Horvath’s three-dimensional watercolor works to directly engage, question, and critique the world in which it exists.

Moving from the faint pastels of the exhibition gallery, visitors entering Room for the Lost Paradise are hit with a technicolor simulacrum of a rococo period room. Multicolor parquet floor designs, which initially appear to be assembled of rare woods are, in fact, varnished watercolors. This floor, which initially hints at a trompe l’oeil verisimilitude, requires a moment of reflection from the visitor. It is, after examination, not a trompe l’oeil effect—intentionally so. Each square reveals the edges of its painted paper strips. A slight unevenness in the floor hints at the floating pieces of plywood fitted together like a jigsaw puzzle. In fact, throughout the room, what initially appears as absolute computer-like precision is instead the interplay of computers and laser cutters and the deeply skilled craft and variation of the human hand. These reveals are not mistakes; they are part of the design—one that winks to the visitor and suggests that all is not right with this world, that a closer inspection will reveal other meanings.

Horvath’s approach to the rococo aesthetic differs from that of his eighteenth-century predecessors. Sure, the swirls, loops, and asymmetrical flourishes are here with abundance. But they are not here to serve the desires and tastes of lords and ladies. For all its nods to aristocratic reverie, it is a room dedicated to examining the self-indulgence, affectations, and manufactured tastes characteristic of late capitalist excess. The room almost calls out to the visitor to take a selfie and post it to Instagram, all the while, inviting those standing outside the room to be voyeurs and watch through the two-way mirror. And, even as visitors snap pics and share them from the air-conditioned confines of the museum, many will remain unaware that the watercolor room around them is a tale of the Anthropocene.

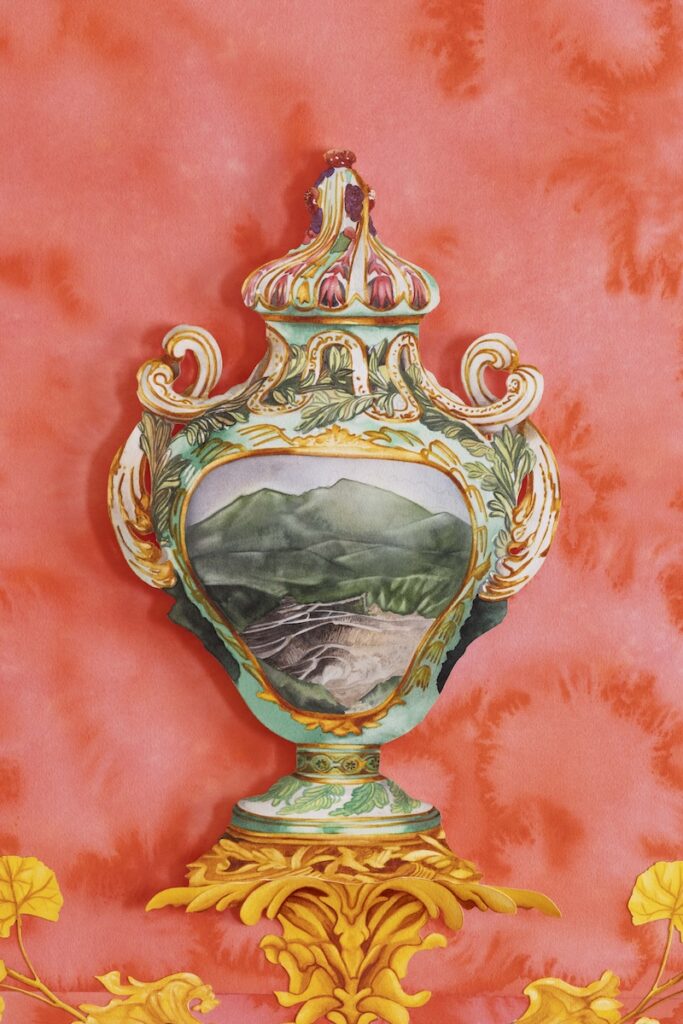

The gilded flowers and plants along the walls represent an assortment of rare and endangered flora, some copied from the herbaria of eighteenth-century explorers and collectors. The rare woods represented on the floors and panels are those once harvested by enslaved workers and stripped from the Caribbean. Twenty-first-century big animal hunters are dressed as rococo fops, holding up an elephant tail or propping up the body of a leopard. A vase, one among the many porcelain and delftware items that line the walls, features a strip-mining operation (Fig. 1). A mounted coral, so often featured in early modern wunderkammeren, reminds the attentive viewer of the warming and acidifying oceans of our contemporary age. The paintings that, on first glance, seem to be copies of Canaletto and Watteau imagine Venice and Cythera in the wake of rising sea levels and climate-change induced storms (Fig. 2). They are rococo versions of the apocalyptic paintings of J.M.W. Turner and John Martin.

The historical context for the objects represented in Room for the Lost Paradise are the intertwined processes of western imperialism, resource extraction, and racial capitalism. Perhaps to represent their interplay, kudzu vines creep across the ceiling. While kudzu is an invasive species that has the potential to disrupt ecosystems, it also has a metaphorical history that speaks to the narrative embodied in the room. Kudzu is, for example, the vine that Alice Walker wrote of in The Color Purple: “racism is like that local creeping kudzu vine that swallows whole forests and abandoned houses; if you don’t keep pulling up the roots it will grow back faster than you can destroy it.”

For all its visual association with the rococo, Room for the Lost Paradise embodies a moral tone—one that would have felt more familiar to late nineteenth-century Decadents, like Oscar Wilde, than to Frederick the Great. On its face, the room seems to celebrate artificiality and the exotic, but, as with Wilde, Horvath uses this aesthetic to challenge bourgeois values, affectations, and sexual conformity, as curator Michael Vetter explains in his symposium response. It explores the decay that emerges from the uninhibited desire for things. The decadence inherent to Horvath’s rococo is a political strategy to excavate the excesses and moral hollowness of what R.H. Tawney once called, the “acquisitive society.” The decadence of the room serves as a watercolor double of its visitors, much as Dorian Gray’s portrait served as a surrogate for his own moral decay.

While the stench of eighteenth-century life is far removed from Room for the Lost Paradise, there is, nevertheless, another decay represented by Horvath, one born with the decadence of the eighteenth century. This decay is one of extractive capitalism, racism, and imperialism. It is a decay that imperils not only human societies, but those of plants, animals, and living systems. In this sense, Room for the Lost Paradise echoes Aimé Césaire’s lines from Discourse on Colonialism (1955), reminding us to recognize both our obligations to humanity and to other living beings:

A civilization that proves incapable of solving the problems it creates is a decadent civilization.

A civilization that chooses to close its eyes to its most crucial problems is a stricken civilization.

A civilization that uses its principles for trickery and deceit is a dying civilization.

Jason M. Kelly is founding Director of the IU Indianapolis Arts and Humanities Institute (IAHI); Professor of History at Indiana University Indianapolis; and Adjunct Professor of Africana Studies and American Studies

Cite this note as: Jason M. Kelly, “Decay and Decadence” Journal18 (July 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7921.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.