In an 1880 edition of L’art du dix-huitième siècle, Edmond de Goncourt mentioned a pair of allegorical pendants (1769; Figs 1 and 2) by Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724-1780), which are now in the collection of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) in Salt Lake City.[1] Subsequent scholarship on the pictures took Goncourt’s identification of subject matter – law and archaeology – as gospel. However, it is important to note that the paintings, executed in the same horizontal format and size, were conceived as companion pieces to hang as overdoors for an unknown patron. Convention dictates that pendants show equivalent subjects, such as law and grace; thus law and archaeology are unlikely companions. A fresh examination of the canonical sixteenth-century Iconologia by Cesare Ripa and its eighteenth-century French edition by Jean-Baptiste Boudard allows us to understand better the complementarity of the pair and provides us with accurate descriptions of the symbolic elements contained within these formerly enigmatic scenes. More specifically, I argue that the picture erroneously identified as an allegory of Archaeology represents instead Fidelity and Discretion, paired with the related allegories of Vigilance, Justice, and Law. Together the pendants refer to individual and societal controls that govern behavior.

Fig. 1. Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Allegory of Vigilance, Justice, and Law (Allegory of Law), 1769. Oil on canvas, 48.9 x 122.6 cm. Purchased with funds from the Marriner S. Eccles Foundation for the Marriner S. Eccles Collection of Masterworks, from the Permanent Collection of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts.

Fig. 2. Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Allegory of Fidelity and Discretion (Allegory of Archaeology), 1769. Oil on canvas, 48.9 x 122.6 cm. Purchased with funds from the Marriner S. Eccles Foundation for the Marriner S. Eccles Collection of Masterworks, from the Permanent Collection of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts.

The designations of Law and Archaeology persisted due in part to the faith placed in L’art du dix-huitième siècle. In the foundational study of Saint-Aubin’s oeuvre, Edmond de Goncourt acknowledged a vague recollection of the images: “…Law and Archaeology, two overdoors, painted and signed, seen at [the residence of] M. Leblanc 20 years ago…”[2] Yet scholars disregarded Goncourt’s distant familiarity with the pictures’ subject matter, even though he and his brother Jules were unaware of their current location.[3] Equally problematic is the author’s cursory description of the subjects. It is not entirely clear to readers that he understood the meaning of the symbols depicted. Nevertheless, Émile Dacier’s groundbreaking study on Saint-Aubin published in 1929-1931, and Kim de Beaumont’s important doctoral dissertation in 1998 maintained Goncourt’s identification without explicating much further.[4]

An exhibition titled The Rococo Age: French Masterpieces of the Eighteenth Century, organized in 1983 by the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, gave curator Eric M. Zafran occasion to provide a persuasive reading of Allegory of Vigilance, Justice, and Law (previously Allegory of Law).[5] Three figures sit under the barrel-vaulted ceiling of Paris’s Palais de Justice, home to the French judiciary during Saint-Aubin’s lifetime.[6] Consulting the French translation of Ripa’s Iconologia by Boudard, Zafran identifies Vigilance, Justice, and Law.[7] Because the painting celebrates three allegorical figures, one wonders why Law is privileged in Goncourt’s shorthand for the title. At left, Vigilance is posed diagonally, offering a visual cue to the viewer of the pendant’s righthand orientation. Vigilance is shown with the characteristic attributes of an open book (bearing the painting’s date) resting atop her lap, an oil lamp burning overhead, and a crane with a stone grasped in its claws.[8] Omitted from other contemporaneous pictures of Vigilance, such as the more economical rendering by Saint-Aubin’s contemporary and academic rival Jean Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 3), the crane’s suitability as an emblem of watchfulness is explained by Ripa:

The cranes flying together, when they would rest securely, one of them holds a stone in its claw; the other[s] so long as the stone does not fall, are secure and safe by the vigilance of their companion, and it falls only when the guard falls asleep, at the noise of which they fly away.[9]

The ease with which one recognizes the above figure attests to Saint-Aubin’s fidelity to established iconography.

Fig. 3. Jean Honoré Fragonard, Allegory of Vigilance, ca. 1772. Oil on canvas, 68.9 x 54.9 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. © Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of René Fribourg, 1953, www.metmuseum.org.

In a 2007 catalogue essay for a monographic show organized jointly by the Louvre and the Frick Collection, De Beaumont argues that a strong foundation in allegory informed the very deliberate drawings produced throughout Saint-Aubin’s career.[10] Prior to the artist’s enrollment at the Académie Royale, during which he vied unsuccessfully for the Grand Prix in 1752, 1753, and 1754, and for a spot at the École des Élèves Protégés in 1753, he held a teaching appointment at the École des Arts. Established by Jacques-François Blondel, the École des Arts gave Saint-Aubin the opportunity to instruct others “in the principles and proportions of the human body; the elements of history required to select appropriate attributes and allegories for princely dwellings, sacred structures, country houses, public buildings, fêtes, and so on…”[11] Saint-Aubin would draw upon this knowledge in the creation of the UMFA’s allegorical paintings many years later.

Fig. 4. Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Gabriel de Saint-Aubin Painting an Allegory of Justice (recto), 1768. Brown ink, wash and pen, 16 x 14.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo by Thierry Le Mage.

A self-portrait sketch (Fig. 4) from the Livre des Saint-Aubin, held in the collection of the Louvre, provides a textbook example of Justice. Dated 1768, one year before the execution of Allegory of Vigilance, Justice, and Law, the drawing shows the artist, palette and maulstick in hand, painting a model in an allegorical guise.[12] In the UMFA’s composition, Saint-Aubin takes greater liberties, combining the attributes of Law and Justice in the figures at the right side of the canvas. Boudard’s Iconologie states that the scales and sword, grasped by the female draped in blue, are elements of Justice.[13] The crown and gold-and-white ensemble of Justice are donned by her companion. Law holds a scepter, which denotes her authority, and appears in proximity to an open book bearing the inscription: IN LEGIBUS SALUS, or “safety in law,” the protection offered to those who adhere to her rules.[14] Visual comparison of the sketch and the finished composition reveal that the model posed for both works, as Justice in 1768 and Law in 1769.

If Allegory of Vigilance, Justice, and Law is readily decipherable, it stands to reason that the picture’s companion also eschews esoteric subject matter. Two women sit adjacent to a Roman-style Corinthian portico, perhaps inspired by Jacques-Germain Soufflot’s concurrent building project of the Church of Sainte-Geneviève, now the Panthéon (1755-1790). A distant time and place is evoked through Greco-Roman architectural elements, a desert-dwelling mammal, and the absence of vegetation in the foreground. It is no wonder that Goncourt believed the subject to be the study of antiquity. An essay penned by Perrin Stein for the 2005 exhibition catalogue French Drawings from Clouet to Seurat discusses a preparatory sketch for the composition previously titled Allegory of Archaeology.[15] Stein makes the first attempt to truly unpack the UMFA’s painting, which has been reproduced several times. Held in the collection of the British Museum, the sketch (Fig. 5) corresponds to the central portion of the work, in which two women are turned toward each other. Stein rightly concludes that the figure on the left is Fidelity due to her alert canine attendant.[16] This designation may be found in the guides of Ripa and Boudard, both of whom name the stamp and key as essential accessories of Fidelity.[17] Ripa explains: “the key and seal are emblems of Fidelity, because they lock up and conceal secrets. The dog is the most faithful animal in the world, and beloved by man.”[18] In Saint Aubin’s interpretation of this allegory, the dog guards a locked trunk and key, on which it is seated.

Fig. 5. Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Study for an allegorical overdoor (recto), ca. 1769. Red chalk with stumping, black and blue chalk, brush and brown, gray, and blade wash, touches of gouache, 218 x 148 mm. The British Museum, London. © Image courtesy of The British Museum, London, www.britishmuseum.org.

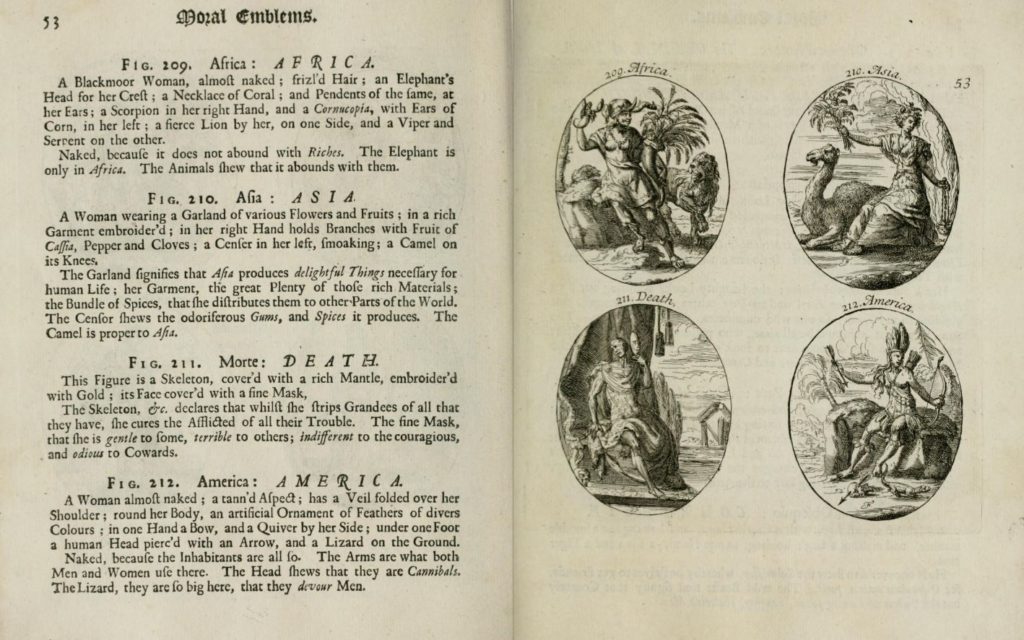

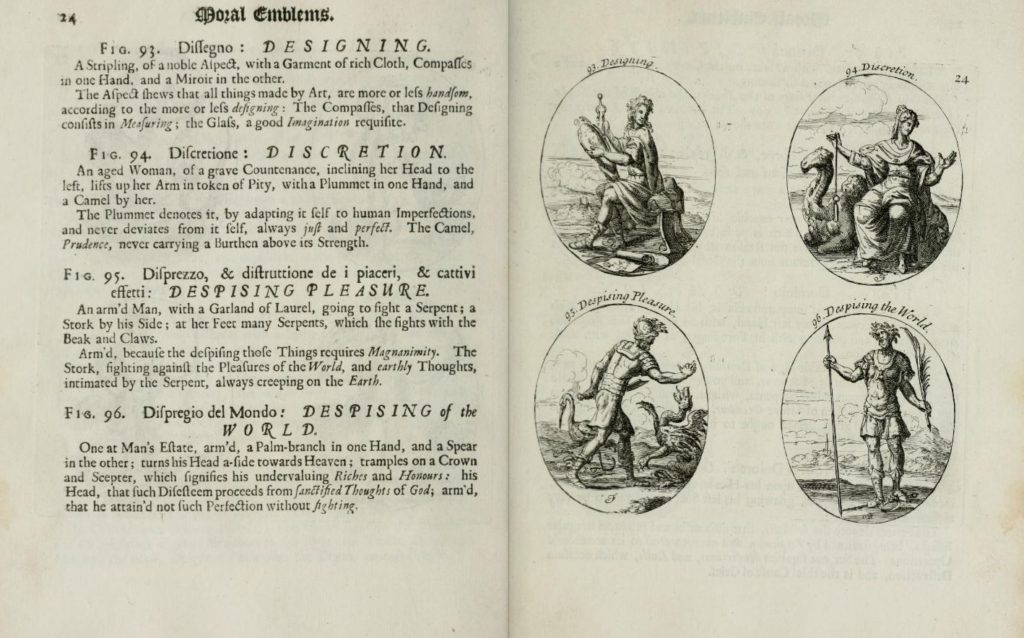

Stein proposes the remaining figure, situated atop a resting camel, is Asia (Fig. 6), an oblique reference to a patron with commercial dealings in the continent.[19] Reviewing Ripa closely, however, I suggest a figure better suited to be Fidelity’s companion. In Iconologia, Ripa describes Discretion (Fig. 7) as follows:

An aged woman, of a grave countenance, inclining her head to the left lifts up her arm in a token of pity, with a plummet in one hand, and a camel by her. The plummet denotes it, by adapting itself to human imperfections, and never deviates from itself, always just and perfect. The camel, Prudence, never carrying a burden above its strength.[20]

Following Ripa closely, Saint-Aubin shows Discretion holding in her right hand a plumb bob, suspended by a golden chain, and raising her left arm in a merciful gesture. One departure is the selection of a youthful woman to represent Discretion; however, this choice is consistent with the models employed throughout the pendants. Emphasizing the role of Discretion in the scene is a mysterious figural sculpture, no doubt plucked from Saint-Aubin’s repertory of drawings of statuary in Paris. A cloaked stone figure emerges to reveal a finger pressed firmly to his lips, encouraging decorum of speech.

Fig. 6. Cesare Ripa, “Asia” in Iconologia: or, Moral Emblems, 1709. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. © Image courtesy of University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, www.archive.org.

Fig. 7. Cesare Ripa, “Discretion” in Iconologia: or, Moral Emblems, 1709. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. © Image courtesy of University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, www.archive.org.

The partnership of Fidelity and Discretion communicates individual duties held in check by Vigilance, Justice, and Law. Saint-Aubin gestures subtly to personal responsibility in Allegory of Fidelity and Discretion (previously Allegory of Archaeology) by placing a handheld mirror at the lower left of the composition, angled toward the viewer, inviting self-identification with the virtues on display. With her foot, Discretion points casually to the painter’s signature “G. d. S. Aubin Pinxit” on a cartellino. Archival research may yield information about the patron and his or her connection to the legal profession, which demands the qualities depicted in the right canvas in the service of those of the left. In the absence of this information, De Beaumont has suggested that the commission was granted by someone “receptive to [Saint-Aubin’s] particular brand of extroverted intellectualism.”[21] Certainly, the first owner of the UMFA’s pendants was familiar with the standards of Ripa and Boudard and conversant in the language of allegory.

Leslie Anne Anderson is Curator of European, American, and Regional Art at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City

[1] Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, L’art du dix-huitième siècle, 3rd ed. (Paris, 1880), I: 431. Goncourt also refers to the pendants critically in an 1873-1874 edition of L’art du dix-huitième siècle. “Qu’eût fait cependant Rome, de Gabriel, s’il eût eu le grand prix? Un peintre d’histoire de la valeur de Subleyras. En effet, deux tableaux que nous avons vus, chez M. Leblanc, signés G. de Saint-Aubin: l’un représentant la Loi, l’autre l’Archéologie, ne promettaient guère plus à l’avenir de Gabriel. L’Académie fit donc bien de le laisser à Paris; car Paris; c’est le maître et le génie de Gabriel.” Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, L’art du dix-huitième siècle. Watteau. Chardin. Boucher. Latour. Greuze. Les Saint-Aubin (Paris, 1873-1874), p. 463. Though the Goncourt brothers collaborated on their publications, I refer to Edmond as the author of revised editions after the 1870 death of Jules.

[2] “…La Loi et l’Archéologie, les deux trumeaux, peints et signés, vus chez M. Leblanc, il y a une vingtaine d’années, et qui sont allés je ne sais où.” Goncourt, L’art du dix-huitième siècle, I: 431.

[3] In Dacier’s 1929-31 catalogue raisonné, it is suggested that the Goncourt brothers saw the paintings in person around 1855. Émile Dacier, Gabriel de Saint-Aubin: Peintre, dessinateur et graveur, 1724-1780 (Paris: G. van Oest, 1929-31), I: 24, II: 45.

[4] It should be noted that De Beaumont turned a critical eye toward the Goncourt’s characterization of Saint-Aubin’s indeliberate working method. Kim de Beaumont, “Reconsidering Gabriel de Saint-Aubin: The Biographical Context for His Scenes of Paris,” in Colin Bailey et al., Gabriel de Saint-Aubin: 1724-1780 (Paris: Musée du Louvre; New York: Frick Collection, 2008), 19-47.

[5] The Utah Museum of Fine Arts enclosed Goncourt’s title in parentheses, opting for the more inclusive descriptive title Allegory of Vigilance, Justice, and Law.

[6] Kim de Beaumont, “Reconsidering Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724-1780): The Background for His Scenes of Paris,” (PhD dissertation, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1998), 528.

[7] Eric M. Zafran, The Rococo Age: French Masterpieces of the Eighteenth Century (Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 1983), p. 58. J. B. Boudard, Iconologie (Vienne: Chez Jean-Thomas de Trattnern, 1766), 150, 160.

[8] Zafran, The Rococo Age, 58.

[9] Cesare Ripa, Iconologia: or, Moral Emblems (London: Benjamin Motte, 1709), 78.

[10] De Beaumont, “Reconsidering Gabriel de Saint-Aubin,” 19-47.

[11] Quoted in De Beaumont, “Reconsidering Gabriel de Saint-Aubin,” 22.

[12] Bailey et al., Gabriel de Saint-Aubin: 1724-1780, 118. The attributes of Justice shown in the sketch Gabriel de Saint-Aubin Painting an Allegory of Justice are the crown, sword, and scales.

[13] Boudard, Iconologie, 150.

[14] Boudard, Iconologie, 160.

[15] Perrin Stein, French Drawings from Clouet to Seurat (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; London: British Museum, 2005), no. 54.

[16] Stein, French Drawings from Clouet to Seurat, no. 54.

[17] Ripa, Iconologia, 30; Boudard, Iconologie, 12.

[18] Ripa, Iconologia, 30.

[19] Stein, French Drawings from Clouet to Seurat, no. 54.

[20] Ripa, Iconologia, 24.

[21] De Beaumont, “Reconsidering Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724-1780),” 478.

Cite this note as: Leslie Anne Anderson, “A Saint-Aubin Allegory Reconsidered,” Journal18 (October 2016), https://www.journal18.org/794

Licence: CC BY-NC