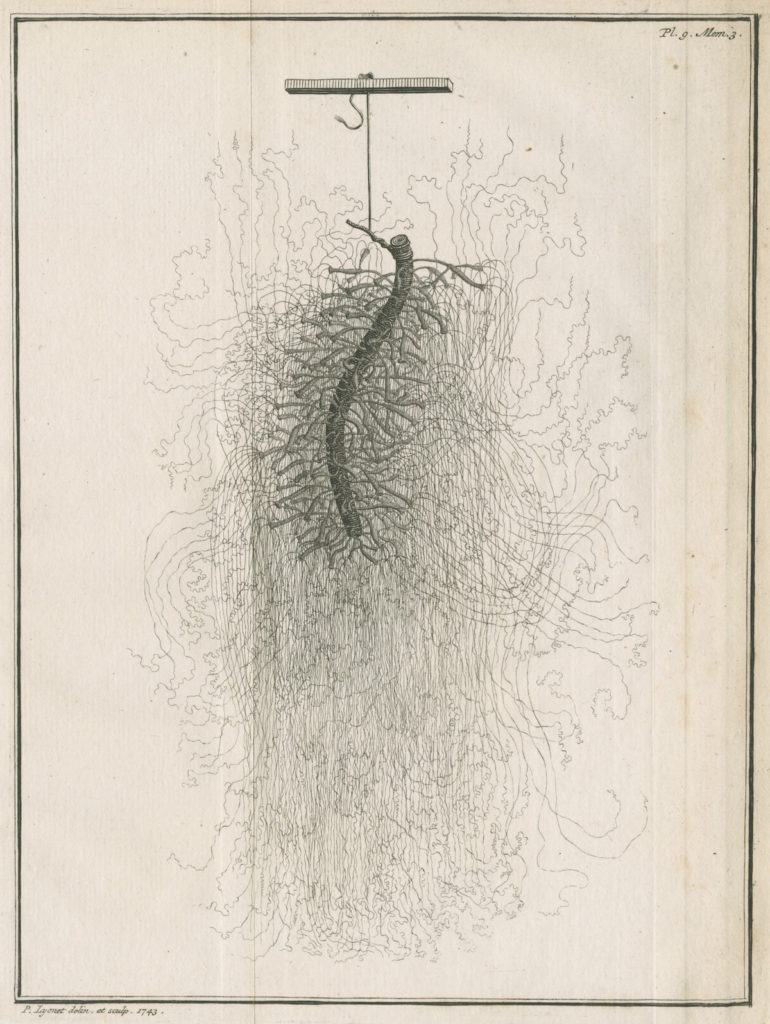

Fig. 1. Pierre Lyonet, Plate 9 from Abraham Trembley, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire d’un genre de polype d’eau douce (Leiden, 1744), etching and engraving. © Royal Society.

In his Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire d’un genre de polype d’eau douce, or Memoirs Concerning the Natural History of a Type of Freshwater Polyp (Leiden, 1744), the Swiss naturalist Abraham Trembley (1710–1784) included a startling figure, one that is not immediately legible (Fig. 1). Plate 9 of his Mémoires presents a confounding whorl of agitated marks, making it difficult to determine whether the specimen displayed is vegetable or animal, one or many. Rather than highlighting any singular, identifiable form, the illustration emphasizes instead the freshwater polyp’s ambiguity. It depicts, in other words, an organism that seems not at all to fit within seventeenth- and eighteenth-century representational schemes. This brief investigation of Trembley’s polyp explores the challenges this image posed for the representation of natural history during the eighteenth century.

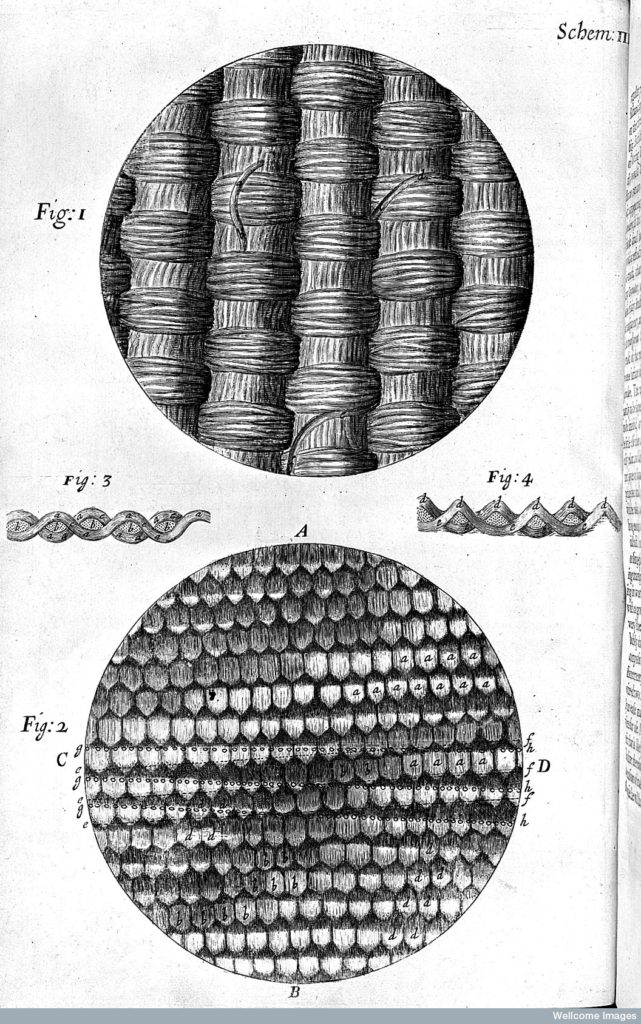

By convention, representational schemes in the early modern period were premised on a rigidly hierarchical system, a Great Chain of Being that extended from the simplest vegetable productions to the infinite complexity of human life, with each discrete link fitting neatly against its neighbor. In order to render indisputable this tidy formulation of the cosmos, natural history illustrations required a visual rhetoric of transparency, as though the image were merely a transcription of the world as seen.[1] The work that set this standard—Micrographia, or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made, by English microscopist Robert Hooke (1635–1703)—often depicts specimens in circular enclosures, as with his illustrations of taffeta and silk, to suggest a faithful recording of the view through the microscope (Fig. 2). Nature appears visually self-evident, and one need only look to apprehend it.

Fig. 2. Schem. III from Robert Hooke, Micrographia (London, 1665), engraving. © Wellcome Library, London, http://wellcomeimages.org

But as art historians Meghan Doherty and Janice Neri have observed, Hooke’s images are not transcriptions but elaborate inventions, composites of different views over time.[2] In the book’s preface, Hooke described his process of discovering a specimen’s form, which—owing to the inherent instability of visual appearances—demanded he examine it repeatedly, in different positions and under different lighting conditions. Only through his repeated manipulations and observations could he ascertain the specimen’s “true form” and “make a plain representation of it.”[3] But this plain representation could not be a copy of the single, empirical view; instead, it was the product of a time-consuming process of synthesis and rationalization that, in Neri’s words, transformed fleeting visual impressions into a “quiet, ordered, and comprehensible world.”[4]

Although Hooke’s work established the standard for natural history illustration, Trembley’s portrayal of the freshwater polyp necessarily ran counter to it, since no degree of rational synthesis could present the organism as easily comprehensible. In a 1740 letter to the French entomologist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (1683–1757), Trembley observed that the polyp possessed a tubular body that bore no internal or external parts, save for long appendages or “threads” that it was capable of moving at will. Its exceedingly simple anatomy seemed to accord with plant life, yet its capacity for spontaneous motion indicated an animal nature.[5] Such ambiguity suggested a creature that could blur the distinction between vegetable and animal and undermine the Great Chain of Being.

Perplexed by the polyp and determined to ascertain its status, Trembley engaged in tireless examination and study of the organism. By 1742, he confidently delivered a report to the Royal Society, declaring that the freshwater polyp was, in fact, an animal composed of an open-ended pouch with numerous appendages:

Their Arms extended into the Water, are so many Snares which they set for Numbers of small Insects that are swimming there. As soon as any of them touches one of the Arms, it is caught. . . .

A Polypus can master a Worm twice or thrice as long as himself. He seizes it, he draws it to his Mouth, and what is more, swallows it whole.

If the Worm comes endways to the Mouth, he swallows it by that End; if not, he makes it enter double into his Stomach, and the Skin of the Polypus gives way. The Size of the Stomach extends itself so as to take in a much larger Bulk than that of the Polypus itself, before it swallowed that Worm.[6]

Despite its simple anatomy, the polyp’s capacity for motion and its predatory habits confirmed for Trembley its animal nature. At the same time, it was an animal like none had ever witnessed, without viscera, muscles, or even a central nervous system.

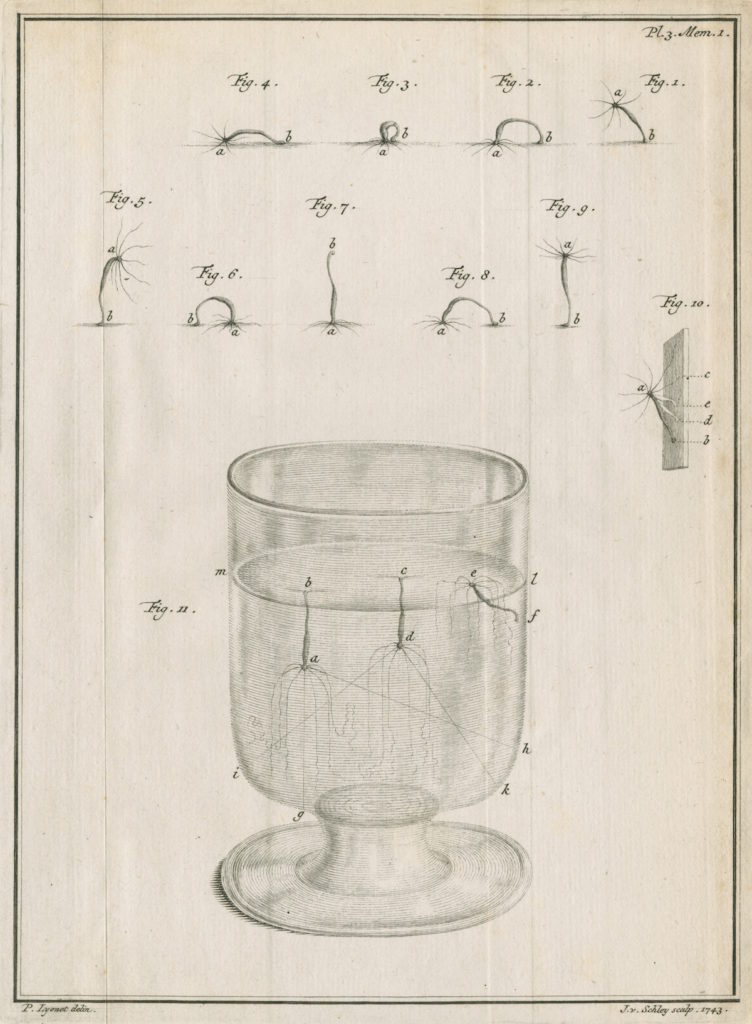

Just as the polyp profoundly challenged the classification of life forms, it also presented challenges for their visual representation. Extended microscopic examination allowed Hooke to discern a specimen’s “true form,” yet the polyp had no true form. A protean creature, it could shift shapes through the movement of its arms and the contraction and extension of its body. Hooke’s rational composites were inadequate for representing the polyp; rather than combining in a single figure numerous views through the microscope, illustrations often include a sequence of figures in an attempt to capture the polyp’s shifting shapes. Another plate from Trembley’s Mémoires does just this, depicting the organism extended and contracted as it propels itself end over end (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Pierre Lyonet (designer) and Jacobus van der Schley (engraver), Plate 3 from Abraham Trembley, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire d’un genre de polype d’eau douce (Leiden, 1744), etching and engraving. © Royal Society.

And yet, while this illustration disrupts Hooke’s representational strategy and the orderly view of the cosmos it presents, it is Plate 9 of Trembley’s Mémoires (Fig. 1) that radically upends both. Although the illustration that opens this essay includes a multiplicity of figures, they are noticeably not in sequence. Rather, many long-armed polyps attach to a twig suspended from a length of twine, extending their arms in a disorienting halo of thin, jittery lines.[7] In this bewildering image, polyp bodies and twig fuse into a single pulsing form, presenting a chaotic, if unexpectedly enlivened, natural world, one that wholly resists the eighteenth century’s taxonomic hierarchy and representational conventions.

Elizabeth Athens completed her PhD at Yale University in 2015 and is now Assistant Curator of American Art at the Worcester Art Museum

[1] See Meghan C. Doherty, “Carving Knowledge: Printed Images, Accuracy, and the Early Royal Society of London” (Ph.D. diss., UW-Madison, 2010), 1–11. As Doherty points out, accuracy is a social construction that depends on accepted standards of truth. Though visual representations are of course mediated knowledge, adherence to particular conventions gives them the effect of transparency and thus accuracy.

[2] Meghan C. Doherty, “Discovering the ‘True Form’: Hooke’s Micrographia and the Visual Vocabulary of Engraved Portraits,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society 66 (2012): 211–34, and Janice Neri, “Between Observation and Image,” in The Insect in the Image: Visualizing Nature in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1700 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 105–138.

[3] Robert Hooke, Micrographia, or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made (London, 1665), preface, unpaginated.

[4] Neri, “Between Observation and Image,” 113.

[5] 15 December 1740, quoted in Virginia P. Dawson, Nature’s Enigma: The Problem of the Polyp in the Letters of Bonnet, Trembley, and Réaumur (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1987), 96–97.

[6] Abraham Trembley, “Observations and Experiments upon the Freshwater Polypus, by Monsieur Trembley, at the Hague,” Philosophical Transactions 42 (1742–43): v.

[7] “La Figure, qui remplit toute cette Planche, représente une partie d’un morceau de bois, que j’ai trouvé entre plusieurs autres dans le mois de Juillet 1742, dans un fossé de Sorgvliet. Ce morceau de bois est couvert de Polypes à longs bras.” See Trembley, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire d’un genre de polype d’eau douce (Leiden, 1744), 226.

Cite this note as: Elizabeth Athens, “Chaotic Life: Representing the Freshwater Polyp,” Journal18 (August 2016), https://www.journal18.org/774

Licence: CC BY-NC