Resemblance—things that look like other things—has played a near universal role in global art and material culture. Gods have been conjured into the temporal realm by their likenesses; portraits of rulers have been revered in the absence of their physical presence. In those two examples, the power of semblance is culturally contingent. Outside of a specific culture of production the signified (god or ruler) does not physically embody the signifier (work of art); it is only referred to in the abstract. Traditionally, it has been the project of the art historian to recuperate the original meaning and function of the things humans have created by a deep immersion in the extant remains of the culture from which they came. But inherent meaning is fugitive in artifacts of human culture, the interpretation of which is destabilized by a ceaseless flow of shifting worldviews. What if we were to give up our speculative search for historical truths and revel in anachronism?

Fig. 1. Left to right: Bearskin moccasins, mid-Mississippi region, United States, eighteenth century, bear-skin, tendons, claws, Musée du quai Branly, Paris; Foot reliquary of Saint Adalard, Italy, sixteenth century, stamped, engraved, chased, and gilded copper, 12.4 x 20.8 cm, Musée national du Moyen Âge – Thermes de Cluny, Paris; Zulu shoe-cane, South Africa, ca. 1910, wood 91.5 x 8.6 x 2.5 cm, Musée du quai Branly, Paris. Installation view, Carambolages, Grand Palais, Paris. Photo © the author.

A reliquary of Saint Adalard, bearskin moccasins, and a Zulu cane (Fig. 1)—just one of many staged encounters between mundane and wondrous things that curator Jean-Hubert Martin brought together for Carambolages (2 March-4 July 2016) at the Grand Palais. (The name of the exhibition derives from the French term for a shot in a game of billiards where a knock-on effect is achieved when a cue ball hits its mark, which hits another ball in turn.)[1] The foot-shaped reliquary is placed next to moccasins made from a bear’s feet by indigenous people of North America; alongside these is a cane with a handle shaped like a boot.[2] They are all feet; we all have feet; the congruence of the human form represented across cultures is rendered as marvelous as it is banal. Another vitrine houses a bust of philosopher René Descartes modeled from a cast of the philosopher’s skull (Fig. 2). It sits next to a case for a rock-crystal vase covered in gold-stamped morocco leather like a luxuriously bound book. Here, the objects are grouped not for their shared appearance, but because the external form of each is determined by an internal structure. This pairing seems to carry a poetic reference to Descartes’ dualism: the materiality of the body exposed with the removal of a facial façade; the shining and ineffable brilliance of the soul hinted at by an exquisite crystal vase hidden from view in a case. Perhaps the vase is missing and just the carapace remains, corpse-like, on view. It is a curious facet of human logic to search for narratives and meanings in objects assembled in suggestive clusters such as these.

Fig. 2. Left to right: Case for a rock-crystal vase, eighteenth century, embossed leather, wood, 25 x 36 x 17 cm, Musée du Louvre, département des Objets d’art, Paris; Paul Richer, Bust of Descartes with a cast of his skull, 1913, plaster, 44 x 40 x 28 cm, Ecole nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris. Installation view, Carambolages, Grand Palais, Paris. Photo © the author.

Apophenia, the tendency to find patterns in random data, has an ancient pedigree in the magical worldviews of fortune telling and astrology, and the pseudo sciences of phrenology and physiognomy. For Carambolages, an engraving after Charles Le Brun’s animal-men studies of a man who resembles a boar is placed next to a Sèvres tureen shaped as a boar’s head. This pairing exposes the paradoxical nature of semblance. For Le Brun, the codification of meaning by resemblance was a serious business. The project to rebrand the artisan as intellectual required a theoretical approach to making legible paintings that could narrate myths and histories as eloquently as written language. Le Brun’s curious physiognomic studies transfer the characters of animals to the people that resemble them to expand the symbolic repertoire of his painted narratives. The creator of the Sèvres tureen played with semblance for altogether different reasons. The tureen makes a delightful play between nature and artifice when placed in the center of a dining table where an actual boar’s head might appear in a feast. In that case, the falsity of semblance is revealed as a conceit of the artist.

Fig. 3. Left to right: Cup, China, Tang dynasty, 618-907 CE, ceramic, 30 cm, Musée national des Arts asiatiques – Guimet; Plat à godrons, Rouen, seventeenth century, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille; Glazed cup, Persia, nineth-tenth century, Musée du Louvre, département des Arts de l’Islam. Installation view, Carambolages, Grand Palais, Paris. Photo © the author.

Appearances can be deceptive. Three colored ceramic vessels, with simple, modern-looking glazes are visual homophones—faux amis of the ceramic world (Fig. 3). To all but the cognoscenti, these bowls from Tang-dynasty China, ninth-century Persia, and seventeenth-century France are much alike. Through such juxtapositions, Carambolages places us in the eye of the storm of the global and material turns in the history of art. But orphaned from the contexts of their production, objects are presented in an a-historical aesthetic continuum that at best facilitates creative engagement with visual culture, and at worst creates fictional links between disparate and disconnected things.

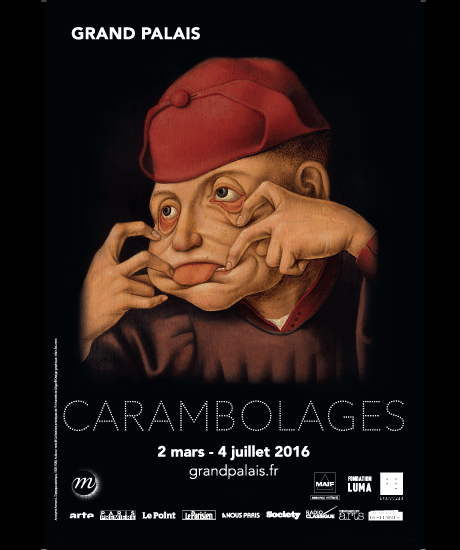

Carambolages is the latest of Jean-Hubert Martin’s controversial experiments in challenging the conventions of curatorial practice though a-historical object encounters. Like his previous projects, Magiciens de la Terre (Pompidou, 1989) and Théâtre du Monde (Pompidou, 2012/ MONA, Hobart, 2013) this exhibition has proved to be divisive with the public (a feature that the Grand Palais celebrated in its promotional videos). Martin’s radical and idiosyncratic curatorial strategy encourages active engagement from the audience to conjure meaning from resemblance. Without the didactic presence of “the expert,” this exhibition forces us to question the value of art historical discourse in the public sphere.

Robert Wellington is a lecturer at the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University

[1] Grand Palais, Carambolages exhibition webpage (accessed 14 August 2016): http://www.grandpalais.fr/en/event/carambolages

[2] Information about the objects on display was only provided outside of the field of vision on screens and via an app available for download.

Cite this note as: Robert Wellington, “Resemblance and Apophenia: Carambolages at the Grand Palais,” Journal18 (August 2016), https://www.journal18.org/759

Licence: CC BY-NC