Fig. 1 Installation view of Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age, 2016. © Photo by Allison White.

Curated by Karina H. Corrigan, Jan van Campen, and Femke Diercks, on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts from February 27th-June 5th, 2016 (and previously at the Rijksmuseum), Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age displays 200 paintings and objects demonstrating the dynamic connections between East and West prompted by the Dutch foray into global trade. Entering the exhibition space, one is immediately struck with the aroma of Asian spices displayed in open canisters: cinnamon, pepper, and cloves, a sensory reminder that spices were the primary impetus behind the world’s first multinational corporation, first stock-issuing company, and first internationally recognizable brand: the Dutch East India Company, known by its Dutch-language acronym of VOC (Fig. 1).

The early seventeenth-century focus on spices quickly expanded as the Dutch began collecting finished products (like porcelain and lacquer) and raw materials (like silk and mother of pearl) for a home market increasingly interested in the exotic, the new, and the luxurious. The Dutch Republic’s elite and its rapidly expanding middle classes avidly collected Asian goods that could be found in homes of varying economic levels, as depicted in interior scenes and still life paintings (there are many excellent examples on view), as well as documented in household inventories. The huge volume of imported goods is represented here by a diverse range of media, among them oil paintings, textiles, ivories, ceramics, printed books, lacquer, metalwork, and works on paper. The material and visual culture of Amsterdam during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries demonstrates the vital role of Asia in shaping the Dutch Golden Age.

The narrative of the exhibition begins with Asian made goods, moves into considering the increasingly integral role such goods played in the lives of Amsterdammers, and finally examines imitations of Asian goods attempted by Dutch craftsmen, showing a gradual incorporation of the foreign into the Dutch aesthetic. Yet the diversity of objects in the exhibition also reveals that the story isn’t simply one of Dutch acquisition and assimilation or of binary hybridity. Rather, there are objects on view that travelled through multiple places, items that combine materials and aesthetics from diverse sources, and works that show how influence and inspiration weren’t unidirectional. Countering the dominant narrative of East to West is a Japanese jacket made from Dutch leather wallpaper and Japanese and Indian depictions of European traders, both of which were made for local markets. There are also objects that indicate a sustained and multidirectional interaction, such as a palampore (bed covering) of Indian cotton embroidered with silk that was made in the Deccan region of India (Fig. 2). Featuring a Chinese floral design with vases copied from a French engraving, it was clearly made to cater to European tastes, following designs provided by European traders.

Fig. 2 Palampore. Deccan, India, 1710-1750. Cotton embroidered with silk and metal-wrapped threads. Peabody Essex Museum, Veldman-Eecen Collection. © Photo by Fotostudio John Stoel.

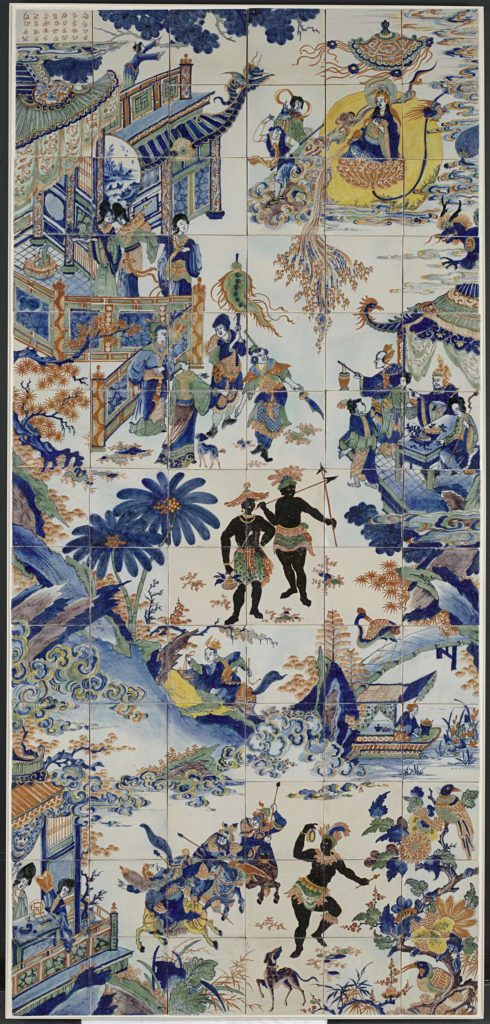

Fig. 3 Tile Panel with a Chinese Landscape, anonymous, 1690-1730, tin-glazed ceramic, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. BK-NM-12400-443. Image source: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

In several sections, the exhibition explores the transformation from imported to imitated goods. Such displays make it clear that many works we think of as typifying the “Dutch Golden Age” were derivative of their Asian exemplars. Visitors are invited to touch samples of European and Asian textiles and ceramics, augmenting the visual experience of seeing works in cases or represented in paintings. This tactile experience allows the visitor literally to feel why so many of these Asian goods were prized for their superior quality. Elsewhere, European transformations of Asian artworks can be seen, as with a display of Persian and Mughal miniatures alongside Rembrandt’s copies after them. This section includes a rarely seen panel from Vienna’s Schloss Schönbrunn containing a collage of these imported images (assembled c. 1762 from Mughal miniatures painted 1600-1720).

Despite the array of attractive and appealing objects, Asia in Amsterdam is not only celebratory, but also considers the inequities inherent in these commercial and colonial relationships. The story of the VOC’s slaughter and enslavement of 10,000 Banda islanders in order to secure a nutmeg monopoly is told prominently and poignantly through a film about a reenactment dance performed annually in the Maluku Islands (The Cakelele Dance of Banda, 2010). The exhibition also shows the gradual slippage from specific foreign references in European visual culture, to the generic exoticism of eighteenth-century chinoiserie. A delftware tile picture lent by the Rijksmuseum features a Chinese scene intruded upon by Brazilian Indians with African complexions – a truly confusing mix epitomizing an increasingly confused concept of the Other that contributed to the ethnocentric ideas of the Enlightenment and beyond (Fig. 3).

The exhibition ends with newly acquired works by Dutch artist Bouke de Vries, reminding visitors of the contemporary relevance of the import of Asian ideas and materials (Fig. 4). In this final encounter, the visitor is left to ponder the question: if the Dutch Golden Age was precipitated by the massive import of foreign goods, how Dutch is the Netherlands?

Fig. 4 Installation view of Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age, 2016. © Photo by Allison White.

Marsely Kehoe completed her PhD at the University of Wisconsin – Madison and is a scholar of the Dutch seventeenth- and eighteenth-century global reach.

Cite this note as: Marsely Kehoe, “Asia in Amsterdam”, Journal18 (May 2016), https://www.journal18.org/667

Licence: CC BY-NC