Displaying historical works in contemporary art museums is a risky – yet potentially rewarding – business. Case in point: Dioramas, an exhibition curated by Claire Garnier, Laurent Le Bon, and Florence Ostende that just closed at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and will have a second venue starting in October at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, was at once spectacular, stimulating, and at some levels frustrating.

Coined in 1822 by Louis Daguerre, better known as the inventor of photography, the word diorama etymologically means seeing through.[1] One can differentiate three different types of dioramas: illusionistic displays, like the ones created by Daguerre; natural history dioramas, mixing taxidermic animals and illusionistic backgrounds;[2] and dioramas depicting humans represented by mannequins.[3] Following the idea that dioramas have served as an inspiration for modern and contemporary artists, from Marcel Duchamp to Mark Dion, the curators chose to display contemporary pieces along with more historical objects. As a result, numerous fascinating artworks were commissioned for the venue, such as a poetic and enigmatic installation by Tatiana Trouvé (2017), incorporated into the middle of the Palais de Tokyo as a transparent and transitional space between the historical and the more contemporary parts of the exhibition. In one of the first rooms, where earlier displays were presented, Armand Morin also paid his respects to Daguerre-style dioramas in Panorama 14 (2013-2017), a beautiful box reproducing a miniature sandstorm in the Canyon de Chelly. Anselm Kiefer played with effects of light and opacity in Family Pictures (2013-2017), and each of his paintings in the show seemed to represent an unstable vision, an unfixed image, coming out of a dream or a distant memory. Visitors were also reminded of some enthralling pieces from the 1980s, such as Charles Matton’s little reconstructions of artists’ studios and movies theaters (L’atelier de Giacometti, 1987; Le Theater Palace, 1989), two sorts of spaces that have a long connection with dioramas and have often been topics for such representations.

Fig. 1. Gerrit Schouten, Model of a Carbet, 1839. Wood, glass, paper, paint, 49 x 65 x 21 cm. Lille, Museum of Natural History. Photo Noémie Étienne.

Importantly, the show also offered a fresh look at many captivating historical objects that have been understudied by scholars. Habitat group and Daguerre-style dioramas are probably the most entertaining, and were certainly the best represented in the Palais de Tokyo show. But dioramas created during the second half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries also represented life-sized human figures, such as Georges Henri Rivière’s fantastic vitrine Du berceau à la tombe for the Musée des arts et traditions populaires, on view at the Palais de Tokyo. However, what was absent from the show were any dioramas of this scale created in a colonial context. In fact, the only place where this type of display was present was in a short film clip of the 2006 movie Night at the Museum, where the actor Ben Stiller, playing a security guard, engages with Sacajawea (played by Mizuo Peck) inside a diorama at the Museum of Natural History in New York. The scene is certainly funny, yet such dioramas were – and still are – serious ideological tools that shape colonial, national, and racial discourses, an aspect that the curators acknowledge in the catalog but do not fully integrate into the exhibition.[4]

Fig. 2. Unidentified Artists, Tavern, second half of the 18th century. Terracotta, wood, paint, textile, glass, 125 x 125 x 69 cm. Museo Nazionale di San Martino, Naples. Photo Noémie Étienne.

Most of the dioramas featuring human figures in the Paris exhibition were, in fact, small displays dating back to the eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries. One of the most interesting works in this regard was an 1839 display of indigenous peoples by Gerrit Schouten, an artist born in Surinam, which was a Dutch colony at the time (Fig. 1). In the very first rooms of the Palais de Tokyo, there were also eighteenth-century scenes of popular gatherings in public places like taverns, reconstructed on a miniature scale often as collective endeavors by unidentified artists (as is frequently the case with dioramas) (Fig. 2). But most of the eighteenth-century examples in the show were intended for religious devotion, several of which were made by women associated with religious orders in France or Italy (Figs. 3, 4, and 5). Such displays portray human figures, often with real hair and glass eyes, set against illusionistic backgrounds. During the Counter Reformation, Franciscans and other Catholic Religious orders used these dioramas to observe and meditate on the life of Christ, particularly in the chapels of the Sacri Monti of northern Italy, in life-sized displays created from the end of the sixteenth century (Fig. 6)[5]. The startling lifelikeness of these dioramas was understood at the time to encourage viewers to become absorbed in the story and to place themselves imaginatively in the represented scene. For early modern scholars, the presence of these religious scenes in the exhibition is a reminder of how such hybrid objects, though still marginalized in dominant histories of art, can convey important eighteenth-century notions of immersion, simulation, and Gesamtkunstwerk, and it introduced a broader audience to these ideas as well.

Fig. 3. Lorenzo Mosvers, Crucifixion, c. 1760. Terracotta, wood, textile, 182 x 86 x 56 cm. Private collection, Naples. Photo Noémie Étienne.

LEFT: Fig. 4. Caterina de Julianis, The Penitent Magdalen, 1717. Polychrome wax, paper, glass, tempera, 53 x 59 cm. Galleria Carlo Virgilio and C., Rome. Photo Noémie Étienne.

RIGHT: Fig. 5. Ignazio Lo Giudice, The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, c. 1710. Polychrome wax, 70 x 79 cm. Galleria Carlo Virgilio and C., Rome. Photo Noémie Étienne.

Whereas many early dioramas were created on a grand scale, the exhibition focused on smaller works, miniatures, and fragments. This choice can largely be explained by logistical reasons: how do you re-exhibit a diorama that might have at one time been housed in its own building (as many of Daguerre’s dioramas were)? In the case of the Sacri Monti displays, the curators decided to evoke them via a large-scale photograph that was reproduced on one of the walls at the entrance of the exhibition. Many visitors likely had difficulty determining what they were actually seeing, as the photographed displays were easy to mistake for photographs of paintings. Indeed, many dioramas are tableau-like: once photographed, they appear as Renaissance windows-on-the-world, imposing on their spectators a particular and fixed point of view. Others, however, are more vitrine-like: they, too, require the spectator to have a specific point of view, but they allow a more flexible form of beholding.

Fig. 6. Giovanni Antonio Orgiazzi, The Last Supper, 1778 (unknown date and unidentified artists for the sculptures). Paint, terracotta, hair, textile, Sacro Monte di Varallo. Not in the exhibition. Photo Noémie Étienne.

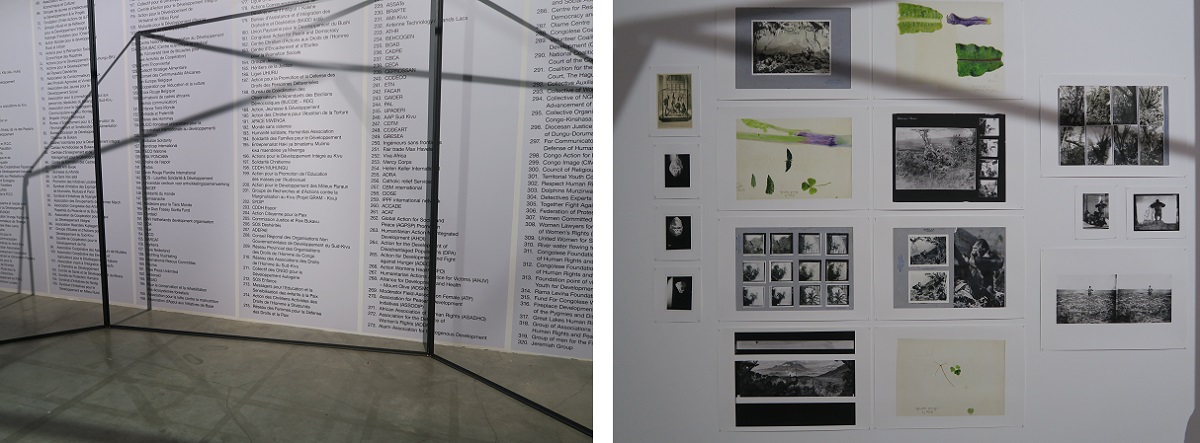

Finally, there have been dioramas that one could physically enter.[6] This third type of installation was utilized by contemporary artist Sammy Balojii, whose Hunting and Collecting (Fig. 7) – one of the most explicitly political pieces in the show – created a sort of frame through which the spectator could enter. Baloji’s artwork is part of a larger research project lead by the artist in 2014 and 2015. It entailed gathering archival images along with a theoretical and formal reflection on Belgian displays of Congo art in in museums such as Tervuren, as well as the hunting practices of taxidermist Carl Akeley for the Museum of Natural History in New York. The inclusion of Baloji’s project was a good occasion to remind the audience of the activist potential of dioramas – not only in contemporary art, but, in fact, since their creation. Along these same lines, Duane Hanson’s Housepainter II (1984), a bronze sculpture of a black man painting a white wall, and Kent Monkman’s Bête Noire (2014), a monumental painting representing a Native American biker in the Wild West, underline the complexity, ambiguity, and political versatility of the media.

Fig. 7. Sammy Baloji, Hunting and Collecting, 2015. Steel, photographs, paper (archives from the American Museum of Natural History, New York, and the Musée Royal de l’Afrique, Tervuren), c. 440 x 885 x 600 cm. Courtesy of the artist and the Gallery. Photo Noémie Étienne.

Overall the curators aimed to keep the definition of dioramas quite open, which makes sense, even if this approach necessitated the inclusion of a great many objects far outside of the three typological categories mentioned above. The exhibition’s thesis of a continuity between historical dioramas and contemporary artworks is certainly a convincing one, yet it is more evoked rather than really demonstrated, perhaps because of the heterogeneity and discontinuity in the selection of works, as well as their sometimes confusing chronological display (contemporary pieces were, for instance, juxtaposed at the beginning of the show with historical objects because they presented formal similarities or, more rarely, direct references). Ultimately, the show draws on scholarly research[7] in order to underline this continuity between historical and contemporary works with a lot of energy, but also with some debatable omissions and sometimes superficial connections. Furthermore, the history of each specific diorama is unclear: little information is given in the wall labels or in the catalog about their multiple makers, the context of their production, or their institutional biographies. As such, in some cases one is prompted to question why certain pieces have been selected over others. Still, Dioramas offered a creative, enjoyable, and certainly thought-provoking exhibition narrative, providing an enlightening historical perspective on contemporary art. It displayed some stunning pieces in a fresh and intelligent way. But perhaps more importantly, it introduced the diorama as a topic to a wider audience, inviting us to consider its trans-historical and global dimensions.

Noémie Étienne is SNSF Professor of Art History at the University of Bern, Switzerland

[1] Guillaume Legall, La peinture mécanique. Le diorama de Daguerre (Paris: Mare & Martin, 2013).

[2] Donna Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, 1908-1936,” Social Text 11 (Winter 1984–85), 19–64; Stephen Quinn, Windows on Nature. The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History (New York: Abrams, 2006); Suee Dale Tunnicliffe and Annette Scheersoi, eds., Natural History Dioramas. History, Construction, and Educational Role (Dordrecht, Heidelberg, New York and London: Springer, 2015).

[3] Alison Griffiths, Wondrous Difference: Cinema, Anthropology & Turn-of-the-century Visual Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002); Karen Rader and Victoria E. M. Cain, Life on Display. Revolutionizing U.S. Museums of Science and Natural History in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014).

[4] Noémie Étienne, “La matérialité politique des dioramas,” in Laurent le Bon, Claire Garnier, and Florence Ostende, eds., Dioramas (Paris: Flammarion, 2017), 186–193; and Noémie Étienne, “Dioramas in the Making: Caspar Mayer and Franz Boas in the Contact Zone(s),” Getty Research Journal 9 (2017), 57–74.

[5] Wietse de Boer and Christine Göttler, eds., Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2013).

[6] For a history of immersive display (which unfortunately doesn’t include dioramas), see: Oliver Grau, Virtual Art. From Illusion to Immersion (London and Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003).

[7] See, for instance, Seeing Through? The Materiality of Dioramas, a workshop on dioramas organized at the University of Bern in December 2016 that featured presentations by Jean-Roch Bouiller, Noémie Étienne, Liliane Ehrhart, Francine Giese, Valérie Kobi, Thierry Laugée, Guillaume Legall, Florence Ostende, Veronica Peselmann, Nadia Radwan, Alexander Streitberger, Mercedes Volait, and Xenia Vytuleva.

Cite this note as: Noémie Étienne, “Dioramas, Before and After,” Journal18 (September 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1934

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.