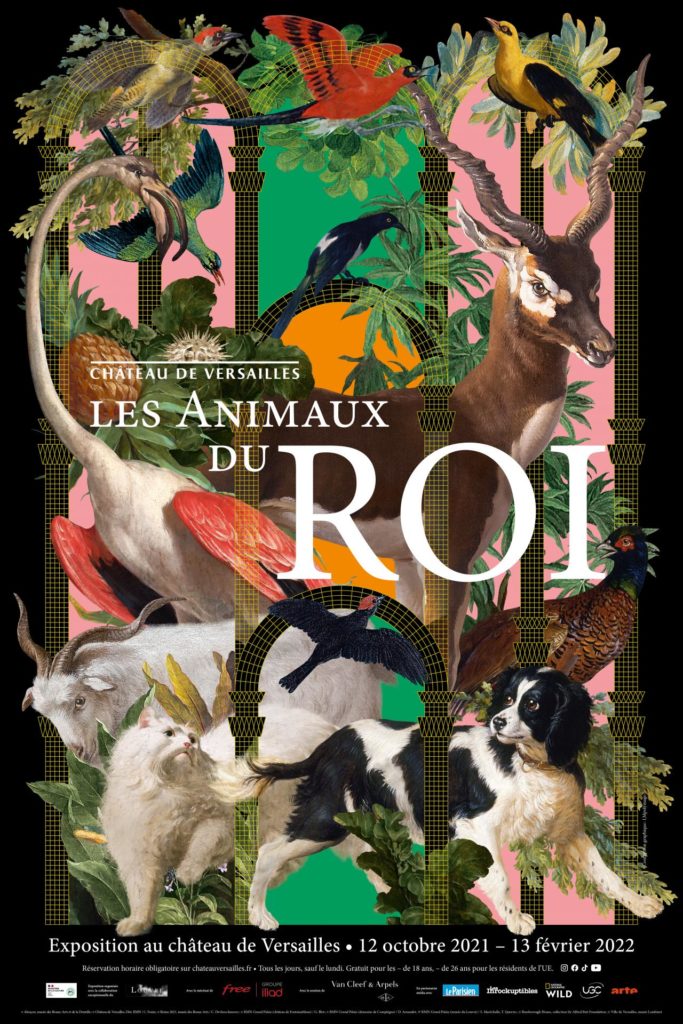

Les Animaux du Roi, Château de Versailles, Versailles, France, October 12, 2021 – February 13, 2022. Curated by Alexandre Maral and Nicolas Milovanovic. Scenography: Guicciardini & Magni Architetti. Lighting: Lionel Coutou.

You are allowed to enjoy this exhibition. Cast off your critical baggage and just relax. It’s okay. Forget your theory, forget ecological thinking, don’t stay with the trouble, and keep your mind off entanglements. Pretend like critical animal studies never happened. Just go with it (Fig. 1). It is okay to be enchanted. You are surrounded by charismatic fauna at every step within this exhibition’s thematic sections. Lions, tigers, bears, foxes, civets, so many handsome birds, horses, dogs, and cats.

You enter through a winding path composed of trellises and fake vines (Fig. 2) and the remnants of the lead animal sculptures that once composed the labyrinth in the gardens of Versailles, destroyed in 1778 to make way for another site of human-engineered nature, the Bosquet de la Reine. The sculptures, which were part of an elaborate display of 39 fountains that illustrated episodes from Aesop’s fables, are now in a state of ruin. The curators have placed these fragmented leaden objects, some of which still betray hints of their original polychromy, on mirrored plinths so that viewers may inspect them from all angles. Both the wall text and the catalogue inform us that these fabled creatures played a part in the “civilizing process” at Versailles by illustrating base emotions, violence, and the beastly side of animality. As Peter Sahlins’s excellent historical essay in the catalogue argues, the sculpted animals of the labyrinth stood in opposition to the mostly peaceful animals who inhabited Louis Le Vau’s menagerie, and who provided exemplars of grace, beauty, and the possibility of living in harmony. These living captives also likely served as models for the sculptures. The two groups of animals performed a historical didactic function as objects of courtly instruction by illustrating what was perceived by human viewers as positive and negative aspects of animality.

Animals were, as the introductory text panel of the exhibition tells viewers, “everywhere present at the domain of Versailles.” The panel, moreover, declares the exhibition’s subject as a novel one, “up until now never really treated.” The exhibition’s thematic sections describe the “presence” and “role” of animals in the courts of Louis XIV, XV and XVI, and focus on the French court as a space of learning and theorizing about them. There is a concerted effort, in the catalogue and galleries, to position the court of Versailles as an outlier in terms of animal welfare and the cultivation of a sensibility that ran counter to the logic of the Cartesian “animal machine.”

Despite the attempt to position Versailles as a benevolent authority, the profusion of damaged animal objects nevertheless establishes one of the exhibition’s repressed themes: the disposability of animal life in the service of powerful humans, notably the sovereigns who ruled over the domain, and the human viewers who encountered the animals of the king in the menagerie of Versailles, in the dissection theater, and as works of art. The ethics of looking at captive animals is not something we are asked to take up as viewers of this exhibition; this is something you have to decide that you want to do. Or not. You don’t have to. It is possible to stay within the comforting, descriptive language of animals fulfilling their role at Versailles as symbols of the sovereign’s will to power, as participants in the royal pastime of the hunt, as humble servants, as mirrors of the civilizing process, and as raw material for the acquisition of scientific knowledge.

The strongest sections of the exhibition propose that the animals who inhabited the menagerie were not merely the property of the King, but were also vital participants in official circuits of artistic production across a range of media. The majority of the galleries feature the scintillating observational life studies of animals at the menagerie by Pieter Boel, Nicasius Bernaerts, François Desportes, and Jean-Baptiste Oudry, among others. These studies anchor the entire show throughout the thematic sections; they are often integrated into galleries alongside finished works of art, such as tapestries, paintings, illustrated books, decorative objects, and the occasional taxidermy specimen. In the section entitled “Birds of the Menagerie,” for example, Desportes’s Triple Study of an Ostrich (likely based on Boel’s study) is installed next to the sumptuous Verdure with Ostrich tapestry of the Birds of the Menagerie of Versailles produced by the Beauvais Tapestry Manufactory (Fig. 3). The pairing asks viewers to consider the moments of encounter with the birds of the menagerie as a key component of the artistic process.

This brilliant intermedial installation is complemented by a taxidermy hornbill, a folio book of gouache studies of the menagerie’s birds (based on Boel’s life studies), and a gorgeous precious stone and marble table featuring intricately inlaid birds. This pattern of relating the life studies to other works of art across media is one of the exhibition’s main strengths. As an added bonus, four of the rarely exhibited vellum paintings of animals who lived in the Versailles menagerie (and later at the menagerie of the nationalized Muséum d’histoire naturelle, where the vellums are now conserved) are also displayed. Another key moment of intermedial dialogue occurs in the room dedicated to the visual culture of the royal hunt, “Hunting: A Royal Ritual,” where the curators have assembled a large wall of five of Oudry’s and Jean-Jacques Bachelier’s unsettling still life fragments of deer hunted by Louis XV, the so-called bois bizarres. Across the room and directly opposite them appears Desportes’s monumental tapestry cartoon for the Old Indies series, in which the ancient motif of a lion attacking a horse becomes a lion biting into a tapir. The pairing suggests the variability and relative openness of the formal conventions of “royal hunt” imagery, forged in dynamic relation to art historical conventions and historical animal subjects who lived in a particular time and place.

The exhibition’s focus on the circuits of tradition, observation, and production fail to address the literal elephant in the room. She has a name, Shanti, and appears in the exhibition in the form of taxidermy. Shanti arrived from Bengal in 1773 and lived at Versailles. She is displayed in a space that is meant to evoke the octagonal panoptic viewing gallery of Le Vau’s menagerie. The “octagon” takes the form of four walls that feature paintings of some of the menagerie’s other residents (Fig. 4), including several works by Bernaerts, such as Beaver Eating an Apple and A Chamois. Shanti is so large (Fig. 5) that she could not fit inside the octagonal space in the gallery and had to be placed behind it. Taxidermy specimens like Shanti, as well as several drawings and prints of animal anatomy such as the disarming vellum painting of a rhinoceros penis by Pierre Joseph Redouté, demonstrate the importance of animal bodies for the acquisition of scientific knowledge. These objects bring us into contact with the dissection ceremonies, where such knowledge operated as political theater. This was the case for the dissection that took place at Versailles in 1681 (in the presence of Louis XIV) of the first elephant of the menagerie. It is here where we might ponder “the presentiment, or even the suspicion, that the order of knowledge is never a stranger to that of power.”[1] In addition to the life studies that populate this exhibition, taxidermy specimens like Shanti call upon viewers to consider the panoply of artistic media in relation to the bodies of captive creatures upon whom it is largely based. These creatures belonged to a sovereign in form and in function: this naturalized fact is named without being critically examined. The exhibition does not ask us to consider the ecological stakes of the submission of all forms of life non-human life to the sovereign’s authority. Nor are we placed in the uncomfortable position of examining our own complicity as viewers in naturalizing this particular set of power relations. It is okay to stay enchanted. The trouble will find us eventually.

Katie Hornstein is an Associate Professor of Art History at Dartmouth College, where she teaches modern European art history and visual culture

[1] Jacques Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign, vol. 1, ed. Michel Lisse, Marie-Louise Mallet, and Ginette Michaud, trans. Geoffrey Bennington (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 279.

Cite this note as: Katie Hornstein, “Les Animaux du Roi: A Review,” Journal18 (April 2022), https://www.journal18.org/6253.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.