Lately, numerous nation states have either advocated for or erected fortified borders to keep out refugees and migrants. In Europe, some states have even opted to leave the international negotiation table altogether in protest over the prospect of multilateral, cooperative solutions to border issues. As conflicts over Europe’s limits continue to rage—particularly with regard to refugees and migrants from the Near and Middle East entering Central and Eastern Europe—it is a timely moment to reconsider the history of border-making practices there. Perhaps unexpectedly, the baroque and rococo galleries of the Bayerisches National Museum (BNM) in Munich offer a rich array of material to consider these issues within the context of a long history of central European and Near Eastern diplomacy, which brought states and territories into contact even as newly erected borders aimed to slice the same states apart. Redesigned and re-installed last year, the current display ought to generate greater interest in a collection that, quite undeservedly, is rarely on the to-do lists of visitors to the Bavarian capital.

The collection’s new installation should also challenge visitors to consider the role that material culture plays in political negotiations more generally and to conceive of both borders and diplomatic negotiation as zones in which multiple parties come into intimate tactile and visual contact with one another. Of interest specifically to questions of cross-cultural interchange in the context of central European border conflicts is a set of objects made during the reign of Kürfurst Max Emanuel, the Elector of Bavaria from 1679 to 1726, who played a leading role as a military commander in the drawn-out Turkish Wars between the Habsburg Holy Alliance and the Ottomans during the late seventeenth century. These works reward close looking thanks to the ways in which they both narrate the history of Central European-Ottoman relations and speak to how material culture played a key role in orchestrating this political history. In particular, this collection draws attention to the roles that tabletops and games served as silent political actors in the early modern diplomatic world. Viewed in their historical context, we can observe how these playing surfaces appeared at the turn of the eighteenth century not only as metaphors for political negotiation, but also as agents around which focused, diplomatic encounters could literally ‘play’ themselves out.

Fig. 1. Game table of Kürfurst Max Emanuel von Bayern, Augsburg (workshop unknown),

ca. 1683-1692. Oak, spruce, ebony, tortoise shell, mother of pearl, 76.2 x 104.0 x 75.0 cm. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich. Photo: © Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich.

Let’s begin with an ostentatious gaming table (Prunkspieltisch), made of tortoise shell and mother-of-pearl in an unknown Augsburg workshop between 1683 and 1692 (Fig. 1). The object was most likely a diplomatic gift from Kaiser Leopold (I) of Austria to his son-in-law Max Emanuel in gratitude for the Bavarian prince’s contributions to the wars of the 1680s and 1690s. The table was not only a symbol of diplomatic alliance, but also cast the nature of this alliance as a ludic enterprise. The surface introduces the viewer (or user) to the key players in contemporary geopolitics: in the border edging around the wooden surface we find engraved medallions containing the portraits of Kaiser Leopold I, Max Emanuel, and their allies. A riot of swirling acanthus weaves these parties together, and also encloses a set of putti triumphantly playing war games with unidentified Turkish figures, who are either chained to the set of allied princes, or in a state of violent dismemberment. The table, whose designs were derived from a combination of prints, reads like popular contemporary propaganda images of the allied victory at Kahlenberg outside of Vienna, where the allied forces defeated the Sultan’s army led by Kara Mustafa.[1] It differs from such topographical battle scenes, however, in key respects: The Turkish actors are minimized and the cartographic rendition of a battle site has been transposed into the diagrammatic language of game boards. The center of the table can be flipped over to reveal boards for chess and nine men’s morris, or removed completely to uncover a backgammon field (Figs 2 and 3). Although the table was likely never used, it symbolically invited a new cast of players to assemble around the previous ‘players’ pictured in the medallions to ‘replay’ narratives of territorial negotiation as a group, connected to one another just like the houses of Wittelsbach and Habsburg.

The relationship between chess or other ‘siege games’ (Belagerungsspiele) and war was well recognized and enjoyed a considerable vogue in renaissance Europe. The Habsburgs commissioned several now-famous board games that conflated their dynastic ambitions with games of military strategy. For example, in Ferdinand I’s backgammon game (Langer Puff) now at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Charles V and the Western Habsburg territories appear on one side of the board, while Ferdinand and the Eastern reaches of Imperial claims appear on the other.[2] What is striking, however, about the Munich table is the way in which not only war but also peace, or the process of alliance making, is materialized as a board game, or as a surface around which multiple people can gather (early modern predecessors, in a sense, of the 1950s board game ‘Diplomacy’). For just as we can view the linked portrait medallions that frame the Prunkspieltisch in relation to topographical battle images, so too can we see them in relation to new genres of diplomatic images that emerged in the wake of the Westphalian agreements of the late 1640s. In broadsheets and, more rarely, in paintings, negotiations of peace and war came to be represented as group portraits of individual diplomats, arranged sequentially around a page in the center of which stands a table. These furnishings, however, are seldom remarked upon in scholarship despite their ubiquitous presence. Other engraved tabletops produced in Augsburg during the same period, like one at the V&A that probably belonged to the Dutch stadholders, illustrate the ways in which individual portraits could be inserted into blank medallions to compose an intricate, and variable, table of alliances upon request (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Tabletop, Augsburg (workshop unknown), ca. 1690-1710. Silver, tortoise shell (engraved). Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photo: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

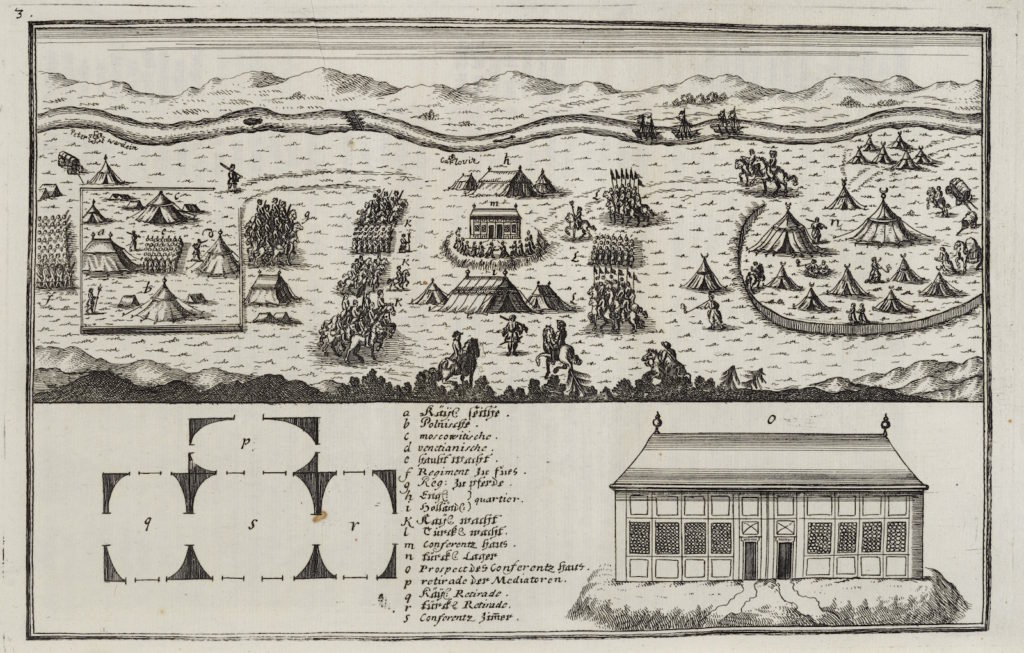

Such objects intimate how peace was understood not only as an abstraction, but also as a product negotiated collectively in the material world. Tables and flat surfaces played a key role in these negotiations as the sites around which diplomatic negotiations took place. The erasure of the Ottoman players from the BNM Prunkspieltisch, for instance, masks the fact that the Turkish wars actually resulted in a peace treaty signed in Karlowitz in 1699. This treaty delineated an agreement between the Habsburg allies and the Ottomans on an unprecedented set of borders that shaped the political and physical map of Europe to this day. A key to the success of these negotiations was the establishment of an even playing field where the players could meet. This field needed to be designed and built. In Slankamen, near Karlowitz, a building was thus erected with multiple doorways that circumvented conflicts over hierarchy or precedence by enabling parties to enter separately and thus approach the surface of the negotiating table as equals (Fig. 5). Once the negotiations were complete, the actors extended the playing surface to the surrounding landscape. Close to Slankamen, the Ottomans and Allies leveled a patch of earth and erected three columns next to which they placed four identical chairs (Fig. 6). These chairs flanked the middle column, which marked the newly negotiated boundary. The bargaining table thus dissolved metaphorically into the ground, upon which the players’ chairs now stood. A visual and tactile ritual then ratified the treaty: the ambassadors grasped one another at the border. Their touch performatively ratified the agreement and marked the boundary not as a cartographic abstraction, but as a zone of mutual contact and agreement; each ambassador would then go on to visit each other’s sovereign, in Vienna and Constantinople respectively.

Figs 5 and 6. Artist Unknown, Prints from Gründ- und Umständlicher Bericht von Denen Römisch-Kayserlichen Wie auch Ottomannischen Groß-Bothschafften, wodurch der Friede oder Stillstand zwischen dem aller-Durchleuchttigst-Großmaechtigst-und Unueberwindlichstem Roemischen Kayser Leopoldo I. und dem Sultan Mustafa Han III. den 26. Januarii, 1699 zu Carlowitz in Sirmien auf 25. Jahr geschlossen und darauf an den respective hoffen zu Wenn und Constantinopel bestaetiget worden (Vienna: Schönwetter, 1702). Photo: © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Kunstbibliothek, Berlin.

There were, however, hiccups in the elaborate choreography. As in a game, bluffing was introduced as a tactical maneuver. Approaching the columns on horseback, the Habsburg ambassador Graf Wolfgang IV zu Oettingen-Wallerstein pretended to dismount in order to trick the Ottoman representative into dismounting first. Realizing the mistake, the latter’s retinue suspended the ambassador in mid-air until Wallerstein alighted on the ground. Following this theatrical boundary ‘play,’ Ottoman and Habsburg agents began to erect an extended series of small mounds (umka) crowned by newly planted trees along the new border. In a cooperative process analogous to taking turns in a game, one side would erect one mound and the other side the next until the border materialized as a mutual endeavor that seemed to spring organically from the earth’s surface.

Fig. 7. Jacopo Amigoni, Kürfurst Max Emanuel von Bayern receives the Turkish embassy in Belgrad, 1723. Oil on Canvas, 66.7 x 48.5 cm. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich. Photo: © Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich.

Borders, however, did not always manifest themselves so symmetrically in representations of diplomatic encounters. Jacopo Amigoni’s small sketch at the BNM for a painting at Max Emanuel’s country palace at Schleissheim, for instance, presents an asymmetrical diplomatic encounter between ‘teuschen’ (Germans) and Ottomans (Fig. 7). The painting presents the moment in which the Ottoman ambassador and his interpreter (Alexander Mavrocordatos, who helped to negotiate the peace at Karlowitz) visited Max Emanuel in his tent after the Bavarian’s victorious capture of Belgrade in 1688. Two putti pull back the tent flaps to reveal the scene, marking the boundary of the image as a threshold into which access to a closed negotiation over border policy has been opened. In this space, there is no table, nor is the playing field even; the Kürfurst sits on an armchair towering over the Ottoman delegation, who huddle on pillows. In Schleissheim itself, however, Amigoni and Max Emanuel’s architects staged the idea of a game-like border encounter around the finished version of the painting. Installed on the wall opposite the entrance to the palace’s principal reception room, the painting was positioned so that Max Emanuel’s gaze directed the visitor to the right, where a set of cabinets were concealed in panels gilded with trophy motifs (Turkish heads on spikes mounted upon golden festoons) (Fig. 8). The hidden cabinets could be opened to expose actual booty gathered from vanquished Turkish camps. These objects could be removed from the cabinets and used as props in the kinds of performances, masquerades and parties that were popular at German baroque courts. Such events might well be understood as border plays themselves, since they tended to feature remarkably interactive forms of collective visual and haptic border crossings.

Fig. 8. Viktoriensaal at Schleissheim (cabinets opened). Photo: © Bayerische Schlossverwaltung, Munich.

In Dresden, for example, Augustus the Strong staged a lengthy set of celebrations occasioned by his son’s marriage to Maria Josepha Habsburg in 1718. At one of these events, the Festival of Mercury, Augustus installed a Turkish military tent filled with life-size wax dolls dressed in Ottoman costumes that represented the Sultan’s Serail. These lifelike dolls were accompanied by a set of life-size paintings based on French ambassador Charles Ferriol’s popular publication Wahreste und neueste Abbildungen des Türckishes Hoffes (first published in Paris in 1714, with editions to follow in German beginning in 1719). These effigies provided a performative mirror for the members of the Saxon court; illustrations of the event present the encounter as a kind of meeting of teams in a reflective face-off with one ordered court examining the other (life-size chess games were another German baroque party practice). At Augustus’s festival, the court – dressed in international ‘drag’ as the Nations of the World – gathered together with servants sporting ‘moustaches à la Turque’ and the Ottoman ambassador to Austria, Ibrahim Pasha, at a banqueting table. This table was shaped like a crescent, a form that conflated a Turkish symbol with the iconography of Diana and apparently served as a fitting centerpiece for festivities that celebrated the ways in which the diplomatic marriage tightened political bonds across borders.

Augustus’s fascination for festive boundary crossings on a magnificent scale was matched, however, by a passion for small games, excellent examples of which are also at the BNM. The performative border plays of events like the Festival of Mercury were regularly translated into Saxon chess sets, frequently made of Meissen porcelain. These games often derived their iconography from diplomatic accounts, like Ferriol’s or Johan Nieuhof’s L’Ambassade de la Compagnie Orientale des Provinces Unies vers l’Empereur de la Chine (1665). Moved from the pages of books to the game board, reportage prints were ‘enlivened’ with sets of porcelain objects, whose bejeweled, pint-sized bodies ironically magnified growing Saxon diplomatic ambitions. (Figs 9, 10 and 10a) These ambitions were founded not only on advantageous marriages but also on Augustus’ economic successes, most famously his ‘discovery’ of the secret to making porcelain. This, combined with the richness of the Saxon mines, found a highly concentrated expression in tiny objects that could be picked up, admired and probed at close range. The depiction of foreign courts in prints could thereby be vividly translated into tangible objects whose qualities expanded, rather than shrank, via intimate encounters.[3]

Fig. 9. Johann Joachim Kändler, Johann Friedrich Eberlein, and Johann Gottlieb Ehder, Chess game with thirty-two figures, Meissen, ca. 1740. Hard-paste porcelain with onglaze colour and gold. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich. Photo: © Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich.

Fig. 10. Heinrich Eichler the Elder, Johannes Mann, and Emanuel Eichel, Chessboard, Augsburg, ca. 1715-1720. Natural and stained mother-of-pearl, stained horn, ivory, brass, copper and pewter, 11.5 x 48 x 48.5 cm. Galerie Kugel, Paris. Photo: © Galerie Kugel, Paris.

Freud once asserted that “touching is the first step towards obtaining any sort of control over, or attempting to make use of, a person or object.”[4] But despite Augustus’s obvious megalomania, the intricate tactile figures on game boards like those at the BNM offer some resistance to the standard narrative of the weakening Ottoman empire’s political marginalization during the eighteenth century. In these various diplomatic objects and ‘game-like’ encounters we can also observe the ways in which the Turkish state became increasingly integrated as a fully materialized player into the European state system. Among the gifts that ambassador Oettingen-Wallerstein brought as affirmation of political parity to the Sultan’s court in 1700 was a silver game board. Even if the Ottomans appeared sometimes as an equal partner, sometimes as a figure of exotic fascination, and sometimes as an exaggeratedly subjugated loser, their position at the negotiating table was perhaps only as precarious as that of other European power players. For while each enjoyed a place at the diplomatic table, the rubric of equality generally belied an intense wrangling over precedence and hierarchy. Understood in this manner, both Baroque courtly games and diplomatic tables can be seen as silent agents of a particular kind: they literally furnished performative contact zones, which drew a broad spectrum of political actors together in order to negotiate boundaries as a mutual, if not always symmetrical, undertaking. Max Emanuel himself was never particularly adept at adopting the potentially nuanced perspectives that such objects afforded. The Kürfurst famously favored gambling over diplomatic games of patience and strategy. Perhaps tellingly, Max Emanuel’s geopolitical ‘gamble’ in the European power game ultimately led to loss and exile both from his own lands and from the diplomatic power table.

As art history has directed its attention in recent years to international networks of exchange, much attention has understandably been paid to the great maritime powers of the modern world. Central Europe rarely figures into the global equation in these narratives. Yet a visit to the refurbished galleries at the Bayerisches National Museum reveals the ways in which even small central European states became caught up in the truly global politics of the baroque period. Moreover, the new galleries highlight the crucial role that material culture played (and plays) in geopolitics. The objects that they contain draw particularly timely attention to an understanding of borders as mutable sites of physical exchange that are mediated through objects and performance. The structures of these objects encourage us to adopt multiple perspectives and to understand – and perform – ‘winning’ as a communal endeavor. The refurbished BNM thereby not only helps to direct art historical attention in new geographic directions, but also proves to be a richly rewarding experience for anyone with even a passing interest in the material and visual nature of modern ‘contact zones.’[5]

Sasha Rossman is a PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkeley and a member of the graduate research colloquium ‘The Real in the Culture of Modernity’ at the University of Konstanz, Germany

[1] Engraver Joachim Wichman’s 1683 print Der Entsatz von Wien in the Austrian National Library in Vienna is an obvious potential reference for the medallions and composition. The leafy friezes, on the other hand, recall ornament prints that disseminated decorative motifs (increasingly well suited for execution in the popular Boulle metalwork technique) towards southern Germany and Austria from workshops in Paris and, especially, the Spanish Netherlands during this period. Objects like the Munich table can thus be understood as negotiating borders in numerous respects. On the spread of French and Northern design to Germany with a particular emphasis on Boulle technique and metal inlay, see the essays and conservation notes collected in the volume Prunkmöbel am Münchener Hof: barocker Dekor unter der Lupe, ed. Renate Eikelmann (Munich: Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, 2011).

[2] Master carver Hans Kels d. Ä. transformed the columns of Hercules from Charles’ insignia (‘ne plus ultra’) into a pair of chess pieces – the king and queen, stand-ins for the human actors playing the game of conquest and territorial expansion. See Elisabeth Scheicher, Das Meisterwerk: Das Brettspiel Kaiser Ferdinands I (Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 1986).

[3] Sets of porcelain were also frequent Saxon diplomatic gifts as the court hoped to stimulate economic growth by providing other courts, including the Sultan’s, with samples (the chess set with engravings derived from Nieuhof and the game pieces made of Meissen “Böttgerporzellan” was very likely also offered by Augustus the Strong to a Swedish aristocrat). At the 1718 marriage festival, Augustus perhaps tellingly staged a market, where Saxon goods were sold at numerous stalls. It is notable that Augustus also marketed himself as a small Böttger ware porcelain doll, one of which can be found at the BNM. These miniatures stood in contrast to a life size straw effigy of Augustus, whose face was made, of course, of Meissen porcelain.

[4] Sigmund Freud, Totem and Taboo: Some Points of Agreement between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics (London and New York: Routledge, 1950), 39.

[5] Mary Louise Pratt, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” Profession 91 (New York: MLA, 1991), 33-40.

Cite this note as: Sasha Rossman, “On Border Play in Eighteenth-Century Europe”, Journal18 (November 2016), https://www.journal18.org/1164

Licence: CC BY-NC