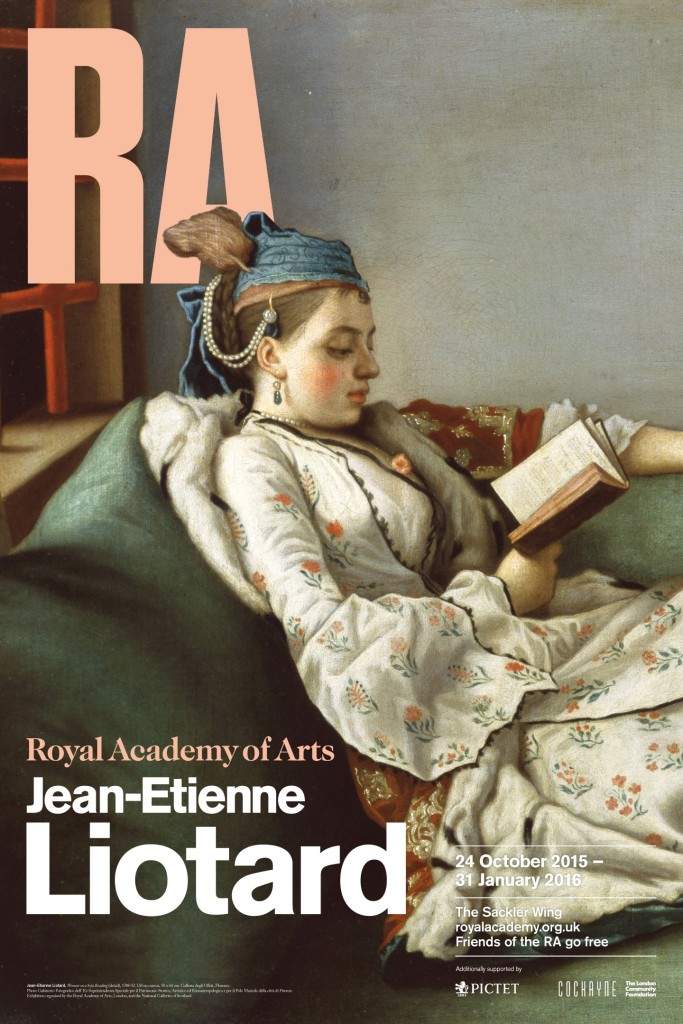

When he advertised “a Collection of Pictures to be seen in Great Marlborough Street, facing Blenheim Street, at Mr. Liotard’s” in 1773, Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702–1789) can hardly have imagined that it would be over 240 years before a substantial number of his works were brought together again in Britain.[1] Although the extravagantly-bearded, exotically-dressed Liotard would likely have been displeased with this lacuna, visitors to the Royal Academy won’t be disappointed by this exhibition, which offers an unrivaled opportunity to explore and appreciate the work of this major eighteenth-century artist.

Born in Geneva to French Huguenot parents, Liotard is perhaps best-known for the turquerie portraits and genre scenes inspired by his four-year stay in Constantinople between 1738 and 1742. Styling himself “le Peintre Turc,” with a long beard and Turkish dress, he spent much of his career working in and traveling between the courts and financial centres of Europe, such as Vienna, Darmstadt, Paris, London, Lyon and Amsterdam.[2] The RA exhibition echoes this trajectory, leading the viewer from Liotard’s self-portraits and portraits of his family, via turquerie, to portraits of his British and continental patrons, both courtly and aristocratic. There are notable absences, particularly from major museums – the Autoportrait, dit à la longue barbe in Geneva, the Portrait of Marie Fargues, the artist’s wife at the Rijksmuseum, and the Getty’s Maria Frederika van Reede-Athlone at Seven Years of Age, for example – but the exhibition’s strength lies in the number of smaller institutions and private collectors who have braved the reputation of pastel’s fragility to lend to the show.

Over seventy works have been brought together at the RA, a selection that demonstrates the breadth of media in which Liotard worked: oils, pastels, chalk drawings, prints and miniatures are all represented. The drawn portraits of the Viennese Imperial children are familiar examples of Liotard’s extraordinary draftsmanship, but it is one of the great pleasures of this exhibition to have the chance to see lesser-known works from private collections. The black and red chalk portraits of Count Jean Didacti and Dr. Theodore Tronchin (both privately owned) are a revelation – it hardly seems possible that such minimal mark-making could produce such likenesses.

Inevitably it is Liotard’s pastels that steal the show. At their best, his pastels are fresh and chromatically rich, their sitters’ complexions soft and velvety. He is equally able to capture the chubbiness of his daughter’s hands and the exquisite lace of a sitter’s dress. Another strength of this show is the number of pendant pairs assembled: if the Chatsworth portrait of David Garrick seems much weaker than the later pendant of his wife, the portraits painted to commemorate the wedding of Julie and Isaac-Louis de Thellusson-Ployard (Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur) are absolutely breath-taking, she wearing a miniature portrait of her new husband on her wrist, while her portrait appears in a ring on his finger. Well-known still lifes from the Getty and the Frick act as a coda to the show, alongside a pricked transfer drawing for La Chocolatière and an extraordinary trompe l’oeil (again, from a private collection) that depicts half a portrait of Empress Maria Theresa as if a wooden shutter is being drawn across it.

Jean-Etienne Liotard, Still Life with tea set, c.1781-83 (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles). Photo courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program.

Pastel’s vulnerability to light, humidity and movement has long been seen as prohibitive to any major international exhibition of the medium, and, by extension, of artists who worked as extensively in it as Liotard.[3] Certainly, there are works at the Royal Academy that have suffered – one sheet of vellum positively ripples beneath its glass; the Royal Collection portrait of Augusta, Princess of Wales has fading and abrasion – but the quality and variety of works assembled strikes a blow to those who believe pastel cannot be successfully exhibited.[4] This exhibition is a triumph and dix-huitièmistes should rush to view it while they still can.

Francesca Whitlum-Cooper is Myojin-Nadar Curatorial Assistant at the National Gallery in London

[1] Catalogue of a Collection of Pictures to be seen in Great Marlborough Street, facing Blenheim Street, at Mr. Liotard’s (London, 1773). The only known copy of this catalogue is in the collection of the Frick Art Reference Library, New York.

[2] Inscription from Liotard’s Autoportrait des Offices, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

[3] Before the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition, Pastel Portraits: Images of Eighteenth-Century Europe, in 2011 (which drew exclusively on works from the tri-state area), the last major exhibition on eighteenth-century pastel was the Exposition de Cent Pastels in Paris in 1908, which again drew on local collections.

[4] That being said, it seems now mandatory to include a selection of pastel crayons and papers at every pastel exhibition: while this undoubtedly helps bring the medium to life, it does feel a bit incongruous to display a box of John Russell’s pastels at a Liotard show. One can’t help but feel that master of self-promotion Liotard would have been a bit miffed.

Cite this note as: Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, “Pastel will Travel: Liotard at the Royal Academy”, Journal18 (2015), https://www.journal18.org/187

Licence: CC BY-NC

Pingback: Liotard at the National Gallery | Neil Jeffares