Melissa Percival writes about her experience of preparing a new exhibition of fantasy figures with the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse.

Exeter, Thursday 5th November

Next week it all becomes real. I’ve received a spreadsheet with a detailed delivery schedule of 78 old master paintings borrowed from all corners of Europe. They will join four paintings from the Musée des Augustins’ permanent collection for our exhibition.

Faces, heads, bodies. A busy gathering of ragged beggars, dashing soldiers, haughty courtesans, absorbed readers and sleeping children that blur academic and art historical classifications of genre painting, portraiture and allegory. Young and old, tender and wrinkled. Close-up views of a single figure whose identity remains a mystery because of dark backgrounds, minimal accessories, flamboyant costumes and ambiguous expressions. Flashes of artistic brilliance, humor and eccentricity. These are fantasy figures, an umbrella term that connects for the first time ever the teste de fantasia of Venetian and Bolognese schools, the tronies of Netherlandish painting, the pitocchi vagabonds of Spain and northern Italy, the Espagnolettes of eighteenth-century France, and British fancy pictures.

When writing my book Fragonard and the Fantasy Figure (2012), I discovered an extensive pre-history to Fragonard’s famous series of sixteen fantasy figures (c. 1769). Yet these works had never been compared with each other, or regarded as a distinct phenomenon in European painting. I realised they were far too beautiful and fascinating to remain hidden in picture archives or scattered in museum collections. Axel Hémery, Director of the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, ‘got’ the exhibition idea when I pitched it to him several years ago. He saw potential for developing my modest eighteenth-century French proposal into a much broader ‘anthology’ of European painting from the late sixteenth to the late eighteenth century.

There followed many absorbing hours of picture research, sharing our findings to draw up a long list of paintings in European public collections. Every so often Axel would temper my ambitions with some practical considerations. Remember Rembrandts are hard to come by; Titians even more so. And don’t even think about transatlantic loans. Some disappointments were inevitable, but somehow we have ended up with over eighty paintings.

It’s difficult to imagine how all those trucks will manage in the narrow cobbled street behind the museum. For last year’s Benjamin Constant exhibition they successfully manoeuvred six-metre canvases – vast panoramas of the Orient and lounging sultanas. Thankfully our pictures have more forgiving dimensions.

It looks like a fairly slow start to the deliveries early next week, but there is an awful lot to do in the last couple of days before we open to the press on Friday November 20th. It will be down to the wire!

Monday 9th November

Axel tells me copies of the catalogue are waiting in Toulouse. I’m so impatient to get there and see it! Meanwhile I content myself with flicking through the virtual catalogue on the publisher’s website and announcing its arrival on Twitter. Background research of this vast subject area tested not only my art historical knowledge but also my ability to read in several foreign languages. I visited libraries in Paris, London and Oxford (hurrah for the Sackler with its generous open shelves and late night opening!) and saw as many of our paintings as money and time would allow. The other contributors responded well to the broad European remit of the project. It was a scramble to pull everything together by the deadline – as a humanities academic I’m used to having more leeway. One very satisfying day was spent bringing out the best in the color proofs with the picture editor, a Photoshop genius.

Tuesday 10th November

The Press and Communications Officer is in touch, with the press pack. I recognize some paragraphs that I drafted. Can I give an interview later in the month to a journalist who can’t make it to the preview? We juggle diary dates.

Toulouse, Thursday 12th November

After travelling to France yesterday, I arrive at the museum today just before 9am. Already there’s a delivery van and a team unloading a stack of cases. The wall panels, which I have only seen on plan, are now in place. The front of the vast fourteenth-century church in this former Augustinian convent has been transformed into a much more intimate space, a feat achieved with low walls and blocks of color. The designer’s vision has been honed by discussion with myself, Axel, and key museum staff. The scheme is shades of grey with deep flashes of red, and one dramatic blue wall at the climax of the show. It feels dynamic and bold.

Examining a Jan Lievens from Pau. Photo: Melissa Percival.

One by one, packing cases are unscrewed, paintings are unwrapped and placed on a table. Jérôme, the paintings conservator, scrutinizes them under a bright light to check for damage and verify the condition report with the assigned courier. Then it’s on to the hanging team, led by Caroline, the registrar, to sort out the hooks and maneuver the paintings carefully into place. Curators know it well, but here is salient reminder for art historians who work principally with unframed digital reproductions: old master paintings are unwieldy three-dimensional objects, and they skew disobligingly as you try to hang them straight. They come in an incredible array of frames, from modest to self-aggrandizing, dull to dazzling. Since many of our subjects are very simple, the more overblown gilded affairs sometimes strike an incongruous note.

Each packing case contains a new marvel. Details jump out that weren’t visible in reproduction; forgotten elements from museum visits made several years ago come back into focus. Jérôme points out retouchings, and the various ways that the paintings have weathered during their long life. Now would have been the optimal time to write the catalogue entries!

Late in the day there is a panic about a missing export license for a painting from the UK. It is unthinkable that one of our carefully integrated exhibits might not turn up. As the native English speaker, I am nominated to phone the Arts Council. Miraculously a calm voice on the other end fixes the problem.

Friday 13th November

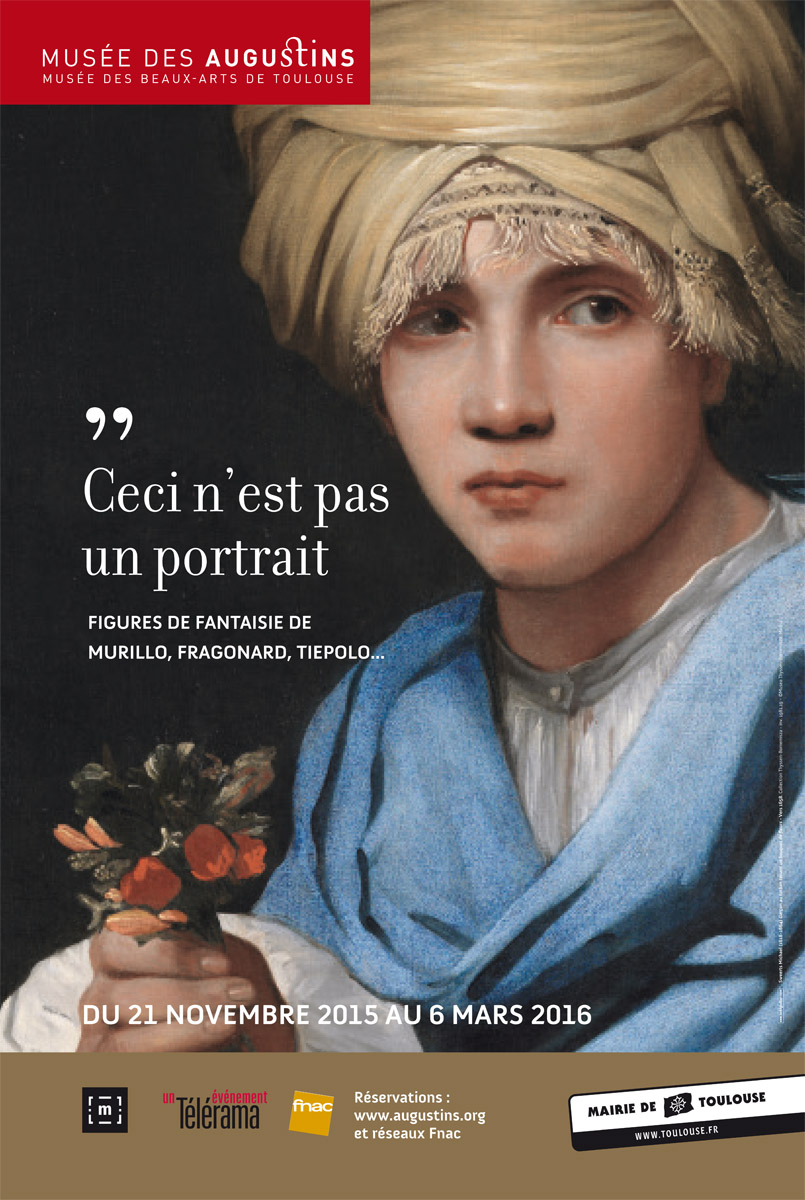

It’s an early start today. Paintings and couriers arrive from France, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy and Germany. Today the absolute masterpieces of the exhibition are emerging: two Fragonards, Greuze’s ambitiously executed Shepherd Boy from the Petit Palais, Annibale Carracci’s iconic laughing man from the Borghese. Michiel Sweerts’s youth (Madrid) stares beguilingly from behind the yellow fringe of his improvised turban. This was the right choice for our exhibition poster, although there was much deliberation at the time.

Greuze’s Young Shepherd (Petit Palais) on the table. Photo: Melissa Percival.

Axel and I were clear from the start that we wanted to blend schools and periods using a thematic presentation that showed patterns and continuities. We needed to avoid rows and rows of old men, or children: speaking for the public, the communications director Geneviève pronounced that that would be far too boring! We have ended up with some sections devoted to universal types (musicians, sleeping figures), but also looser, more evocative themes like Inner Lives (inspired by Michael Fried’s notion of ‘absorption’), Laughter and Sarcasm, and the Laboratory of the Face. This innovative approach is starting to pay off with some unusual juxtapositions. For example, two contemplative women leaning on ledges respectively by Willem Drost and Robert de Séry. Both paintings, by coincidence, are from Lille, yet probably have never been placed side by side before. By the end of the day we have hung nearly half the paintings.

That night comes the first news of the terrorist attacks in Paris.

Saturday 14th November

In spite of news reports that the borders are closed, I manage to fly out from Toulouse to London on Saturday morning. There is a strange, tense atmosphere at the airport.

Exeter, Monday 16th November

One of our major lenders is nervous about shipping a prize work because of the attacks. But the transportation company reports that there is no problem. So business as usual. But there is uncertainty in the air. And a sense of the closeness of tragedy.

Tuesday 17th November

Back to Toulouse again. Late at night in the Toulouse metro, rushing to catch the last train, I meet our Sweerts boy in a turban, larger than life, on a rotating advertising stand. A bizarre, highly gratifying encounter with a very familiar face. It’s no longer a private affair.

Exhibition poster of Sweerts’s Boy with a Turban in the Toulouse metro. Photo: Melissa Percival.

Toulouse, Wednesday 18th November

The exhibition space has gained in depth and dimension since I was last here, not just with the dozen new paintings that have been hung, but also because the wall texts and graphics are starting to go up. The lighting people have been at work too, bringing drama and magic to the pictures. And the museum education team has started setting up the “parcours familial,” with playful, inventive activities for children…and grownups!

Of the new arrivals, Balthasar Denner’s wrinkled old woman (Vienna) is already turning heads. It’s not hard to see why this painting caused a sensation in London in 1721, and was quickly snapped up by the Habsburg Emperor Karl VI who paid a ridiculous sum of money for it. You really can see the pores of the skin, justifying why Denner was dubbed the “Porenmaler.” In total contrast, Frans Hals’s treatment of a humble fisher boy (Antwerp) is jaw-droppingly confident, achieved with just a handful of strokes.

Thursday 19th November

The UK shipment is unpacked, and it’s a chance to chat in English with the couriers. A Ceruti from Belfast, a Crespi from the Fitzwilliam, Murillo’s much anticipated Flower Girl from Dulwich, a Morland from Saltram House travelling with a National Trust registrar who lives just up the road from me. Couriers viewing the emerging show have generally have been very positive, and it feels great that the vibe is traveling back home with them.

There’s a lot to do today, but we are on schedule. Eventually, like a jigsaw piece, the last picture is placed on the wall (a Dosso Dossi from Modena). Axel and I go round reading the wall texts spotting missing French accents and other errors; my skills as a French language teacher are unexpectedly put to good use. When we leave at around seven, the designer and the education team still have a few hours’ work ahead.

Installation shot with paintings by Bordone and Bloemaert . Photo: Melissa Percival.

Friday 20th November

It’s the big day. There’s a morning press preview with Parisian and local journalists. Coffee and viennoiseries are laid out to put them in a good mood. Axel and I take them on a marathon tour of the exhibition. In the first room a light bulb has blown and our Schalcken, a candlelit composition, is even darker than it should be. Later I have a TV interview (torture), followed by a radio interview (easier).

There is time for a rest before the evening opening. When I return the museum is lit up expectantly and there is a big crowd at the door. Dignitaries make speeches in the cloister, and then it’s time to take the VIPs on a tour of the show. With well over 500 people in the church space, the echoing acoustics completely drown out my voice.

Much later, once visitors have left, I sit down with museum staff and our families for a fantasy supper served by an imaginative local caterer. Our starter is entitled “Ceci n’est pas un portrait” and served in a flat ramekin to look like a face. The fish course is inspired by the basket-load of Ceruti’s fisher boy (Florence).

Saturday 21st November

I take a leisurely stroll round the exhibition with my husband. The museum is buzzing, and cash tills are ringing up ticket money – not that admissions will ever cover the vast transport costs we have incurred. This is a blowout show, but right now it feels worth it. We have received a nice review in the Toulouse daily paper. The sun shines and life is good.

Ceci n’est pas un portrait: Figures de fantaisie de Murillo, Fragonard, Tiepolo… is at the Musée des Augustins, Toulouse, until 6th March 2016.

Melissa Percival is Associate Professor of Art History and French at the University of Exeter

Cite this note as: Melissa Percival, “Ceci n’est pas un portrait: A Curator’s Diary”, Journal18 (2015), https://www.journal18.org/172

Licence: CC BY-NC