In the Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery of the China Through the Looking Glass show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a flat, uncut semiformal robe for the Jiaqing Emperor (r. 1796-1820) was suspended next to a Dries Van Noten Autumn/Winter 2012-13 ensemble, comprised of a jacket cinched at the waist with a black belt and pants. From afar, the similarities between the two were startling: same colors, cloud and dragon motifs, as if the uncut textile was next in line on a conveyor belt to be cut and sewn into a contemporary coat. Up close, their differences were clear. No attention was paid to the specific frontal or profile view of the dragon’s head in Dries Van Noten’s garment, nor was the imaginary creature positioned properly. Unlike the eighteenth-century imperial robe, designs were printed and not embroidered, creating an offset, pixelated effect on the surface of the coat.

Despite these clear distinctions, comparisons like these most forcefully struck a nerve with museum visitors that exhibitions on “China” rarely do. As one slips down the rabbit hole of searching for “authenticity” or “accuracy in representation,” one was also reminded that this show never claimed to be about China. Its function was not to serve as a pedagogical tool in explaining the history of Chinese dress or theories on orientalism or post-colonialism per se. The frustration and discomfort of wanting it to be, on the one hand, about China – and becoming increasingly disillusioned by this self-imposed desire – and, on the other, not wanting it to have anything to do with China – but becoming aware of the eerie familiarity between fact and fantasy – is at the heart of the show. What China Through the Looking Glass accomplished was not simply to highlight the fallacies of representation but rather to go one step further by showing, through extravagance, that there was never anything “Chinese” that it claimed to represent.

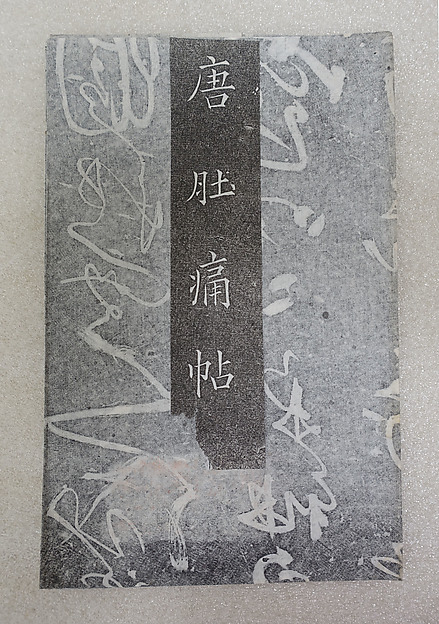

The various floating signifiers of the show hover tendentiously above semantic anchors. For museum-goers, this detachment between motifs (as indices, symbols, icons) and their meanings was uncomfortable. The twelve symbolic emblems that appear on Qing emperors’ royal robes became headdresses in milliner Stephen Jones’s cosmos. What is considered a clear status marker of the Son of Heaven in any art historical scholarship on Qing dress was transformed by Jones into an abstracted headpiece for faceless, mechanized, and mass-produced figurines, devoid of any of iconographic significance. A rubbing of cursive script calligraphy attributed to Zhang Xu in the eighth century – the fanciful performance of the difficulty in controlling one’s brush when in physical distress (stomach problems, in this instance) – became lines in Christian Dior’s cocktail dress.[1] Repeated as a pattern, each character of the brush and ink letter served as a design unit, a formation of lines that denotes less its semantic referent and more its syntactic placement along the A-line brim of the dress.

Zhang Wu, Letter about a Stomachache, 19th-century rubbing of 10th century carving (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Image courtesy of www.metmuseum.org.

Both historical fact and fiction, however, are, and never were, stable in their replication. The show succeeds in highlighting the amorphous boundary between the two through fashion, a world constructed from patterns of emulation that follow the ebb and flow of the market and its trends. Take pagodas, for instance. In the eighteenth century, at the height of European chinoiserie, pagoda-like motifs were literally transported as flat, surface designs devoid of any depth and meaning and fitted into the relevant fashions of the period.[2] “Pagodas” could appear in any scale and material – from minute hand-painted motifs on wallpaper to larger-than-life pagoda-esque structures in European gardens. The endless semantic possibilities presented by these enigmatic signifiers created industries built on pattern books and costume plates.[3] Jean-Baptiste Pillement (1728-1808), for example, published multiple folios entitled A New Book of Chinese Ornaments after arriving in London in 1754, and this trend continued well into the nineteenth century, when Owen Jones produced his now infamous A Grammar of Chinese Ornament.[4]

Unlike these early modern translations, couture designers included in China Through the Looking Glass sought to reanimate the flatness and surface of these traveling motifs, leading viewers to believe that there might be more behind their glistening surfaces – a depth perhaps. But this desire for a particular set of meanings behind the clothing is consistently blocked by the sheer materiality of these garments. “Luxury objects think with us materially,” as Jonathan Hay puts it, in reference to Qing decorative arts, and, indeed, the “surfacescape” of the clothing stimulates our senses and tells us that it is communicating something, but that, as frustrating as it may be, its meaning (or its function, as it were) is precisely what we see.[5]

This plays out in many forms featured in the exhibition, as direct, formal dialogues with each other. Jean Patou’s black chiffon dress featured delicately beaded images of Rococo women swinging over a three-tiered structure with flared roofs (a “pagoda,” perhaps).[6] Attention was paid to the horizontality of the structure by lining select borders of the first level in bright turquoise beads. Patou’s 1920s gown highlights a particular accent that is enforced by later garments, such as those in Yves Saint Laurent’s controversial Fall/Winter 1977-8 collection based on the concept of an opium den. Dresses emphasized a drop-waist, while more structured garments such as coats had what would later be referred to as pagoda sleeves, so named because of their dramatic flared cuffs.[7] In these two instances, even the simplified, imaginary “pagoda” was translated not in its entirety, but instead transliterated into mere horizontals and curves that could come together in any configuration. And, indeed, Tom Ford took his last bow at Yves Saint Laurent during the Fall/Winter 2004-5 collection with the return of the “pagoda” in the form of quilted satin pagoda shoulders. They resembled miniatures peaks that sat at the intersection of the sleeve with the body and emphasized not only the horizontality of the shoulders but also the upward trajectory of the flare.[8]

What China Through the Looking Glass successfully brought to the conversation on orientalism and its imprint on the Western imagination is the possibility of building on surface. Rather than seeking to find an “authentic” or “original” in the depths of meaning behind the ensembles on display, the show asked its viewers to rest, however uncomfortably, on their shiny, glistening surfaces, and, most importantly, to witness how whole imaginary worlds are made on these surfaces by enigmas that have no answers, where meaning implies form, visibility, and their material replication.

Michelle Wang is Assistant Professor of Art History and the Humanities at Reed College in Portland, OR

[1] Andrew Bolton et al, China Through the Looking Glass (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015), 163.

[2] Richard Martin and Harold Koda, Orientalism: Visions of the East in Western Dress (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994), 16.

[3] Here, I borrow Homay King’s use of the term “enigmatic signifier” to describe foreign objects that appear in films as “objects, riddles, and metaphors…[that] all implicitly draw an association between Asian things and things that defy traditional Western modes of rational cognition.” Homay King, Lost in Translation: Orientalism, Cinema, and the Enigmatic Signifier (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), 3. King employs Jean Laplanche’s psychoanalytic term to describe how objects often perceived as foreign to an individual are often replicated and consequently received by others as even further removed from their initial otherness “to the point where whole populations of the globe appear to be sealed off by a thick wall of uintelligibility.” King, Lost in Translation, 4.

[4] Adam Geczy, Fashion and Orientalism: Dress, Textiles, and Culture from the 17th to the 21st Century (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2013), 58.

[5] Jonathan Hay, Sensuous Surfaces: The Decorative Object in Early Modern China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2010), 13.

[6] Bolton et al, China Through the Looking Glass, 213.

[7] Bolton et al, China Through the Looking Glass, 94.

[8] Bolton et al, China Through the Looking Glass, 222-3. For more examples of ready-to-wear items from this season with pagoda shoulders, see Tom Ford and Bridge Foley, Tom Ford (New York: Rizzoli, 2008), 340, 394-5.

Cite this note as: Michelle Wang, “China in Wonderland”, Journal18 (2015), https://www.journal18.org/141

Licence: CC BY-NC