Anne Seymour Damer, Shock Dog, c.1782 (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Image courtesy of www.metmuseum.org.

“The Oddity of her Atchievement [sic] is striking!—The Marble Statues from a Female Hand!—But so it is, and at least in the Work of the Two Dogs, with so much Merit in them, that Bacon himself, or at any Rate the best Pupil of Bacon need not have blushed at owning them.”[1]

So the Public Advertiser proclaimed in 1784, hailing an unusual debut in the exhibition rooms of London’s Royal Academy. With these “Marble Statues,” Anne Seymour Damer (1748/9-1828) became the first female sculptor to display her work in the Academy’s annual show.[2] More than two centuries later, two of her works newly enhance the British Decorative Arts gallery of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Recently acquired by the Met, they finally expose Damer’s rarely-displayed oeuvre to a North American audience.

Despite studying sculpture from her teenage years, the aristocratic Damer only began exhibiting in her widowhood, when she had full legal control of her work. Beginning with wax modeling, a traditionally “amateur” medium, she had advanced to sculpting in terracotta, bronze, and, eventually, marble, a material with which she was clearly quite proficient by her Academic debut. She went on to complete dozens of public and private projects over the course of her career, including a ten-foot statue of Apollo for the Drury Lane theatre, while exhibiting thirty-two works at the Royal Academy as an ‘Honorary’ exhibitor from 1784 to 1818. The Met’s new acquisitions, Damer’s Caroline Campbell, Lady Ailesbury (probably late 1780s), a marble bust of her mother, and her Shock Dog (probably 1782) in Carrara marble, intriguingly illustrate Damer’s willingness to play with genre conventions, even while working with, and mastering, the highest of sculptural materials.

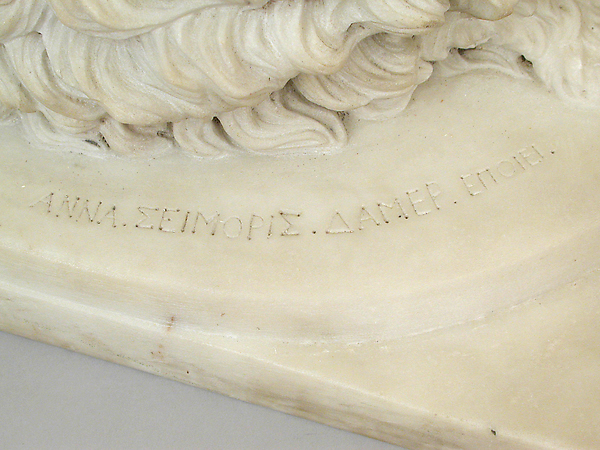

Anne Seymour Damer, Shock Dog (detail of signature), c. 1782 (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Image courtesy of www.metmuseum.org.

The coupling of Damer’s bust of her mother with her Shock Dog perfectly encapsulates the multifaceted ambitions that infused her works, parading her classical knowledge, aesthetic understanding, technical prowess, and humor all at once. Damer was born into privilege, and both works, signed in Greek, tout her classical education. She inscribed “ΑΝΝΑ. ΣΕΙΜΟΡΙΣ. ΔΑΜΕΡ. ΕΠΟΙΕΙ” (“made by Anne Seymour Damer”) on the dog’s oval platform; while “Anne Damer the Londoner made [this]” and “Anne Seymour Damer made [this] of her friend and mother” adorn her mother’s portrait.[3] She additionally carved two Latin claims of authorship onto the portrait bust.[4] These were not baseless allusions to learning; Damer had studied both languages, even complaining about her slow progress with Greek throughout the 1790s in her diary and letters to friends.[5] The depiction of Caroline Campbell further displays Damer’s erudition by imitating classical aesthetics. Damer portrays her mother in classical guise, veiled and calm, exuding an inner light. In fact, she made a copy of the bust for her mother’s tomb, choosing to keep this piece until her own death.

With the Shock Dog, by contrast, Damer imbues technical prowess with humor. Damer’s devotion to her favorite terrier, Fidèle (French for “loyal,” “faithful,” or even “follower”), was well known to her contemporaries. Nearing her death, she steadfastly requested to be buried with only her sculptor’s tools and Fidèle’s ashes. The Shock Dog entertainingly raises such a faithful companion to the high status of a marble portrait subject. She depicts the dog in an almost noble manner, and the animal is seemingly aware of its high position in the eyes of its beholder. Was this, possibly, tongue-in-cheek? How much would Damer have been challenging Academic standards? One can only imagine the reactions of visitors to the Academy in 1799, seeing Damer’s marble dog next to portrait busts, if indeed this is the “dog, executed in Carara marble [sic]” exhibited by Damer that year.[6] Or would it have been placed near George Eckstein’s “Model of a bull” and “Model of a dog,” also exhibited in 1799? Regardless, as with the bust of her mother, a basic human relational impulse radiates from the work. In fact, such relatability arguably brought the Shock Dog to the Met, as a gift of Barbara Walters in honor of her own beloved canine.

Anne Seymour Damer, Shock Dog, c.1782 (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Image courtesy of www.metmuseum.org.

Damer remains one of the only known English female sculptors of her era. While undoubtedly given many unique opportunities from her earliest years, no other female aristocrat advanced her art into the public sphere to any comparable degree. Nor did any other woman of Damer’s background actively pursue sculpture, a physically arduous medium, quite different from the ‘polite’ arts most upper-class women were encouraged to practice. Damer not only cultivated a public career as a female sculptor, but she vigorously and repeatedly demonstrated her own learning and skill. To date, studies of her work have too often focused on controversial aspects of her personal life, particularly her notorious relationship with the writer Mary Berry (whose portrait she sculpted in 1793). Yet while surviving works by Damer are rare, her career merits greater attention.[7] The placement of her Shock Dog and Caroline Campbell in a gallery devoted to historical context lets viewers, hopefully, study the works in an environment similar to that experienced by Damer’s contemporaries. A new generation can now contemplate the “striking!” “Oddity of her Atchievement.”

Paris Amanda Spies-Gans is a PhD candidate at Princeton University in Princeton, NJ

[1] “For the Public Advertiser,” 1784. From the Royal Academy of Arts Archive, London: Royal Academy Critiques 1768-1842, CRI/I 1638-1793 / Volume 1, 134r.

[2] For Damer’s biography, see Alison Yarrington, “Damer, Anne Seymour (1749–1828),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [accessed 14 Nov 2015]. The most rigorous studies of her career are Alison Yarrington’s “The Female Pygmalion: Anne Seymour Damer, Allan Cunningham and the Writing of a Woman sculptor’s life,” Sculpture Journal 1 (1997) and Susan Benforado’s unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Anne Seymour Damer (1748-1828) Sculptor (University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, 1986). The classic study remains Percy Noble, Anne Seymour Damer: A Woman of Art and Fashion, 1748–1828 (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, and Co., 1908). She has additionally been the subject of two recent biographies: Richard Webb, Mrs D: The Life of Anne Damer (Studley, UK: Brewin Books Ltd., 2013) and Jonathan David Gross, The Life of Anne Damer: Portrait of a Regency Artist (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014). See also her page on the Orlando Project. She was painted by Richard Cosway in a Miniature portrait of Anne Damer now in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

[3] All translations are from the Met. Damer signed the bust of Caroline Campbell twice in Greek: “ANNA ΔAMEP H LONDINAIA EΠOIEI” (“Anne Damer the Londoner made [this]”) under the bust’s right shoulder, “ANNA ΣEIMOPIΣ ΔAMEP EΠOIEI ΦIΛH MHTHP AYTHΣ” (“Anne Seymour Damer made [this] of her friend and mother”) on the back of the head. See the “Object Information” section on the Met’s website for both Shock Dog and Caroline Campbell.

[4] Damer also inscribed the marble base of Caroline Campbell twice in Latin. The front reads “CAROLINA CAMPBELL ARGATHELIAE DUCIS, FILIA” (“Caroline Campbell, daughter of the Duke of Argyll”), while the left touts “ANNA SEYMOUR DAMER FECIT” (“Anne Seymour Damer made [this]”). Again, see the “Object Information” for Caroline Campbell on the Met’s website.

[5] These complaints surface frequently in her Notebooks, held by The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

[6] Entry 1104 in the Royal Academy Exhibition Catalogue from 1799 reads “A dog, executed in Carara marble __ Hon. Mrs. Damer.” This was the only work she exhibited that year.

[7] Other works by Damer include: Sir Joseph Banks, bronze bust, British Museum; Mrs Freeman as Isis, marble bust, Victoria and Albert Museum; and Elizabeth (née Farren), Countess of Derby, marble bust, National Portrait Gallery, London.

Cite this note as: Paris Amanda Spies-Gans, “Shock Dog! New Sculpture at the Met”, Journal18 (2015), https://www.journal18.org/132

Licence: CC BY-NC