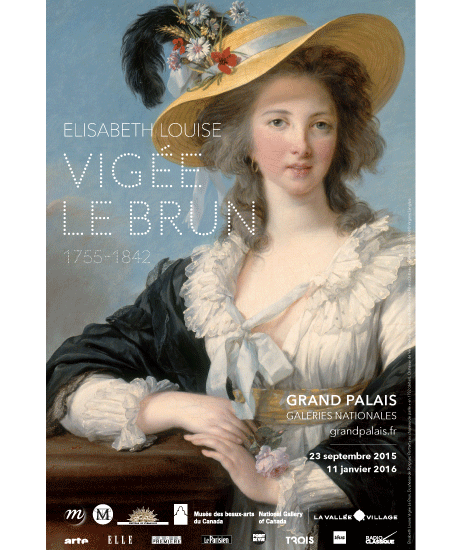

Vigée Le Brun, the most famous female French painter before the Revolution, has finally been recognized by a retrospective in her native country. The Parisian exhibition, to be followed by stops in New York and Ottawa, represents a landmark occasion to appreciate Vigée’s career from the late Ancien Régime to the July Monarchy, including an important focus on her long period of exile (from 1789 to 1802) as a result of her relationship with the French royal family. The Grand Palais display comprises approximately 130 works – mostly paintings since few drawings survive – and combines iconic images like portraits of the French queen Marie-Antoinette with many works from private collections that are scarcely known or have never been published.

Daughter of a pastellist and elder sister of a writer, Vigée married art dealer Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Lebrun in 1776. Although the marriage was unhappy, it provided her with access to her husband’s stock of old master paintings, which contributed greatly to her artistic education, as did a fruitful apprenticeship with Gabriel Briard (a mediocre artist but good teacher) and strong encouragement from fellow artists Gabriel-François Doyen and Joseph Vernet. Vigée’s early career is mostly dealt with thematically in the exhibition, through self-portraits of the artist brandishing her palette and claiming equality with her male colleagues; images of children poised between allegory and realism; and fashion pictures like her scandalous depiction of Marie-Antoinette en gaulle from the Salon of 1783. Also present are images of Vigée’s family and supporters – most notably her masterful depiction of artist friend Hubert Robert – and a range of aesthetic influences from Raphael to Rubens to Greuze. These influences coalesce in Vigée’s exquisite self-portrait with her beloved daughter Julie, an intimate and modern reworking of the traditional composition of the Virgin and Child that also channels the writings of Rousseau. In addition this section features Le Concert espagñol, a Spanish-inspired fête galante, and La Paix ramenant l’abondance, an allegorical subject that enabled Vigée to gain access to the French Royal Academy in 1783 despite strong opposition from its director, Jean-Baptiste-Marie Pierre. Included too are relevant works by her contemporaries, most notably Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, who is often compared with Vigée and is represented here by her gorgeous, full-length Self-Portrait with Two Pupils of 1785.

Portraits executed by Vigée during the final decade of the eighteenth century in Rome, Naples, Vienna and Saint-Petersburg pay homage to a European aristocratic community, while also testifying to the transformative impact that contact with Italian old master paintings and British outdoor portraits had on her work. Several of these portraits highlight Vigée’s ability to adapt her style to fit her subjects, an idea exemplified by her sensuous depiction of Lady Emma Hamilton dancing as a bacchante in front of Mount Vesuvius. Lady Hamilton’s seductive portrayal contrasts sharply with that of the artist’s rendering of Madame Adélaïde and Madame Victoire, the two surviving daughters of Louis XV, who are shown in exile in Italy with a soberness far removed from their royal identity, and with that of a Liechtenstein princess in the guise of Ariadne abandoned on Naxos, an echo of the sitter’s conjugal misadventures. Artworks from Vigée’s later years following her return to Paris in 1802 conclude the show. They comprise a range of new portrait subjects from the Empire to the Restoration, whose pictorial interpretations are tinted with a romantic note, as well as an astonishing series of eight landscapes – only a small portion of these survive from the nearly two hundred such works she recorded in her mémoires – made directly from nature in pastel, a medium she continued to favor and master.

Although this monographic exhibition attempts to claim for Vigée Le Brun both technical perfection and social achievement, there is a certain monotony in the installation that threatens at times to become boring and to detract from the artist’s lively, sensitive treatment of her subjects. Yet despite this minor misgiving, this is an unmissable opportunity to rediscover Vigée’s powerful if somewhat melancholic evocation of a bygone Europe, immortalized by her brush as it moved irrevocably into the modern age.

Benjamin Couilleaux is conservateur du patrimoine at the Musée Cognacq-Jay in Paris

Cite this note as: Benjamin Couilleaux, “Vigée Le Brun at the Grand Palais”, Journal18 (2015), https://www.journal18.org/122

Licence: CC BY-NC