Fig. 1. Workshop of Frans Geubels (after Raphael), Triumph of Bacchus, ca. 1560. Wool, silk, and gilt metal-wrapped thread, 495 x 764 cm. Le Mobilier National. Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis.

For the past year, The Getty Center in Los Angeles has celebrated the reign of Louis XIV during the tercentenary of his death. Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV, which opened on December 15, 2015 and runs until May 1, 2016, is the last major event in this program. Three years in the planning, the exhibition brings together twelve tapestries collected, inherited and commissioned by Louis XIV from the Mobilier national in Paris (formally the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne) along with tapestries and prints from the Getty’s collection, Charles Le Brun’s design sketches from the Louvre, and more besides. This must-see show offers a sophisticated encounter with tapestries seldom on public display, often reserved for the decoration of French presidential residences, including the Élysée palace.

Inspired by the vast collection of tapestries assembled during Louis XIV’s reign, the exhibition is arranged in roughly chronological order and divided into three themes. It begins with the pieces collected by the Sun King, or at least bought on his behalf for the decoration of the royal palaces. The Triumph of Bacchus (Fig. 1) designed by Raphael hangs opposite the entrance. Still vivid despite being woven in the sixteenth century, this tapestry is in an excellent state of preservation. Indeed, all of the works on display were expressly chosen for their bright colors and legible designs so as to lure in a local Southern California audience who might be unfamiliar with or initially resistant to this medium. But this desire to appeal to a broad public does not compromise the scholarly integrity of an exhibition that deepens our understanding of tapestry collecting, design, production, and display under Louis XIV.

The exhibition continues with works inherited by the Sun King, including examples woven at the Louvre tapestry workshop established by Henri IV, one of the precursors to the more famous Gobelins Manufactory founded by Louis XIV.[1] This section shows the development of tapestry production in seventeenth-century France, from the stiff and mysterious designs after Antoine Caron for the Artemisia series, to the sumptuous flesh and billowing draperies of Simon Vouet’s Old Testament scene.

Fig. 2. Workshop of Jean Jans the Elder, Jean Jans the Younger or Jean Lefebvre (After Charles Le Brun), The Entry of Alexander into Babylon, ca. 1665-1672. Wool, silk, gilt metal- and silver-wrapped thread, 495 x 810 cm. Le Mobilier National. Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis.

The last part of the exhibition is devoted to tapestries commissioned for Louis XIV and includes two important works restored specifically for the show. One of these, The Entry of Alexander in Babylon (Fig. 2), is a highlight. Cleaned, conserved and freshly lined, it has more than paid for its upkeep as a key object in the exhibition. The story of its production and display is elaborated in the following gallery with a series of Le Brun’s original drawings for the painting after which it is modeled on view, along with a partially preserved cartoon used for another edition of the tapestry.

Among the prints and drawings in this gallery is a diminutive sketch by Sébastien Le Clerc of the original tenture (set) of the Alexander tapestries displayed in the Gobelins Manufactory in 1694 for the visit of the surintendant des Bâtiments, Édouard Colbert, marquis de Villacerf. The sketch, a study for the frontispiece to a set of small prints after the Alexander series, proposes an alternative order for the presentation of these images. The Entry of Alexander into Babylon hangs at the far end of the gallery, while the Queens of Persia at the Feet of Alexander is in the process of being hoisted up onto the wall at the far right, a direct swap of the two pieces with which the series conventionally starts and finishes.[2] This revised order is played out very effectively for other works in the exhibition. The monumental prints after Charles Le Brun’s Alexander series have been the subject of exhibitions and scholarly attention twice in recent years at the Getty Center.[3] Hanging these prints in the alternative sequence proposed by Le Clerc’s study is subtle evidence of an intriguing dialogue between specialists at the Getty Museum and Research Institute.

Fig. 3. Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV (installation view). © The J. Paul Getty Trust. Photo by Rebecca Vera-Martinez.

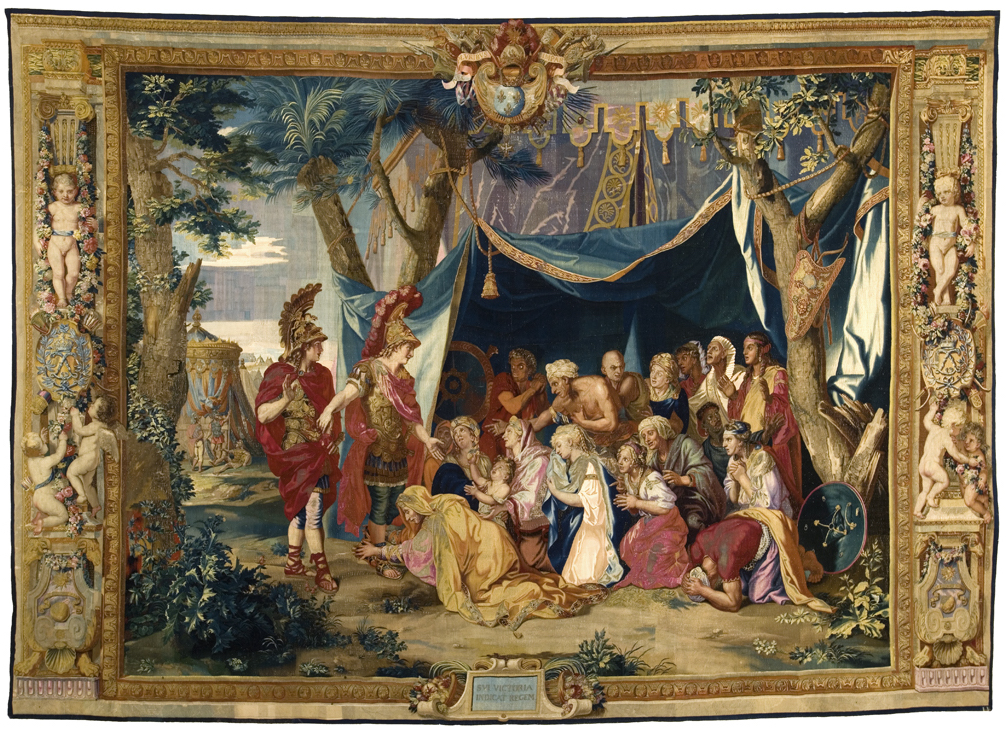

The Alexander tapestries on display also follow this amended arrangement to striking effect (Fig. 3). As you circle around from left to right to admire The Queens of Persia (Fig. 4), you are invited to compare the figure of Alexander in this piece with that of Scipio in The Reception of the Envoys from Carthage that hangs in the first gallery (Fig. 5). The juxtaposition makes for a convincing visual argument that Charles Le Brun was inspired by this earlier design when devising his most iconic work.

Fig. 4. Workshop of Jean Jans the Younger or Jean Lefebvre (After Charles Le Brun), The Queens of Persian at the Feet of Alexander, ca. 1665-1672. Wool, silk, gilt metal- and silver-wrapped thread, 480 x 367 cm. Le Mobilier National. Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis.

Fig. 5. Workshop of the Dermoyen Family (attrib.) (Design in the style of Giulio Romano), The Reception of the Envoys from Carthage, ca. 1530-1555. Wool and silk, 458.5 x 732.8 cm. Photograph by Victoria Garagliano/©Hearst Castle®/CA State Parks.

A canonical painting in the history of Western art, Le Brun’s Queens of Persia at the Feet of Alexander has been a source of endless fascination for scholars of the ancien régime. Two of the contributors to the symposium Apollo and Arachne: Louis XIV and the French Royal Collection of Tapestries, held on January 23-24, 2016 to accompany the exhibition, sought to expand the literature on this work. Louis Marchesano, the Getty Research Institute’s Curator of Prints and Drawings, astutely observed that the wear and tear visible on a print of the Queens of Persia that appears partially hidden in Nicholas de Largillière’s famous portrait of Le Brun is part of the complex narrative of this painting. Barbara Gaehtgens proposed that Hephaestion, the subject of mistaken identity in this painting, who defers to the real Alexander before him, is a veiled reference to the Grand Condé. Harboring ambitions for the French throne, Condé, like his cousin the king, was often compared to the ancient Macedonian emperor. Le Brun’s painting, Gaehtgens persuasively claimed, puts Condé in his place.

Other highlights of the symposium included Getty conservator Jane Bassett’s brilliant research into the metal wrapped threads used in the tapestries on display, and Wolf Burchard’s analysis of the Visit of the King to the Gobelins, a tapestry from the Histoire du Roi series. Bénédicte Gady presented her exciting discovery that a series of allegorical scenes of the history of Louis XIV’s reign may not have been abandoned designs for tapestries, as previously thought, but were perhaps instead cartoons for lost painted textiles. Florian Knothe’s keynote lecture examined the Gobelins as a “colony of artists,” that included a system of training and education rivaling that of the more famous Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. Speakers at the symposium left the audience in no doubt of the importance of tapestries in the age of Louis XIV, despite what remains being but a shadow of their former splendor.

With faded colors and perished silks, it might be hard to persuade a new audience why early-modern tapestries were once more treasured than their painted counterparts. The splendid examples chosen for Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV, complemented by an excellent scholarly catalogue and an insightful public program, go some way to address this problem, demonstrating the value of the curator’s expertise in the public display of art.

Robert Wellington is a lecturer at the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University

[1] On the Louvre Tapestry workshop see Isabelle Denis, “The Parisian Workshops, 1590–1650,” in Thomas P. Campbell (ed.), Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2007), 123–139.

[2] Louis Marchesano and Christian Michel, Printing the Grand Manner: Charles Le Brun and Monumental Prints in the Age of Louis XIV (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2010), 58–9.

[3] Marchesano and Michel, Printing the Grand Manner, and Peter Fuhring, Louis Marchesano, Rémi Mathis, and Vanessa Selbach, A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660–1715 (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2015).

Cite this note as: Robert Wellington, “Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV,” Journal18 (March 2016), https://www.journal18.org/477

Licence: CC BY-NC