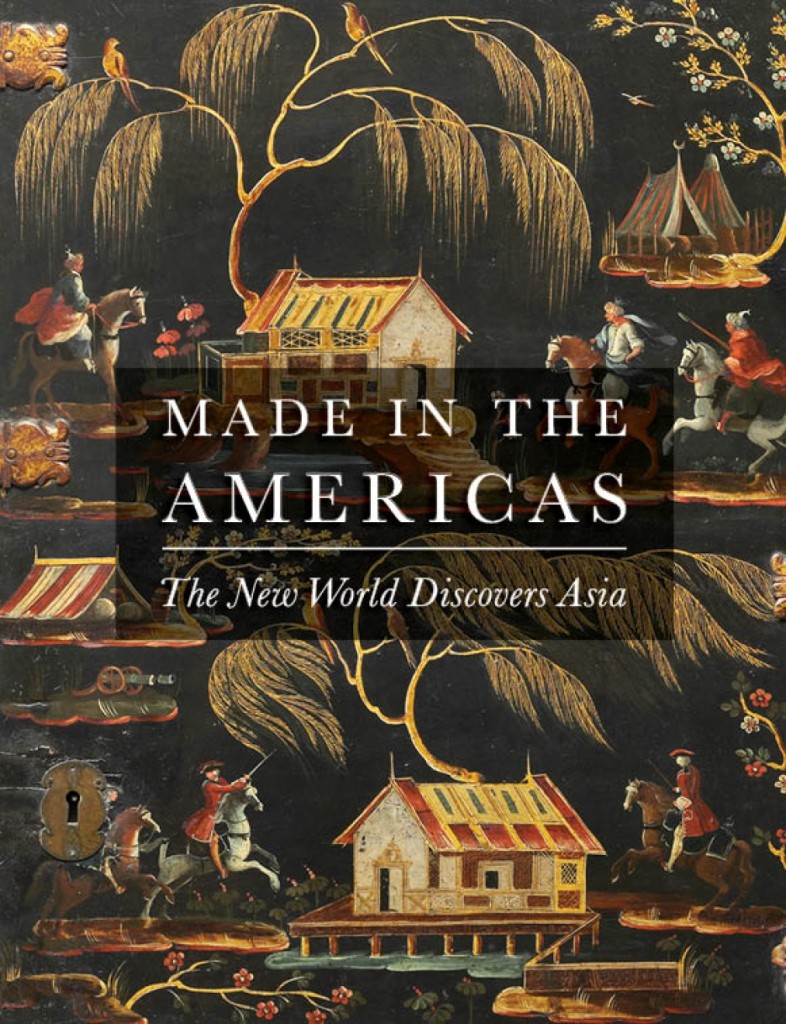

Passing through what is now southwestern Mexico in 1763, the Spanish Capuchin friar Francisco de Ajofrín paused to praise a local artist: “Today there flourishes a celebrated painter, a noble Indian named Don José Manuel de la Cerda, who has greatly perfected this faculty [of painting lacquerware], so that it exceeds in luster and delicacy the lacquers of China.”[1] A black lacquer desk-on-stand signed by De la Cerda is the star of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts’ striking exhibition, Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia. With its waving willow trees, Turkish tents, winged Pegasus, and quaint scenes of European gentry, this object draws together European, Islamic, East Asian and pre-Colombian artistic traditions. The work owes its color scheme and airy vignettes to East Asian lacquered objects that traveled via Manila to Mexico on enormous Spanish galleon ships that sailed across the Pacific Ocean beginning in 1565. Yet De la Cerda, an artist of Spanish and indigenous descent, combined pre-Colombian traditions of lacquer (made from insect fat and chia oil) with East Asian visual inspirations to create a hybrid art.[2] Made in the Americas, with just under one hundred objects, presents material evidence for the surprising, ironic and at times unsettling interactions that occurred between Asia and the New World in the early modern period.

The exhibition, like many recent shows, exhumes hybrid trade objects from museum storage to prove, as the exhibition’s opening wall-text states, “globalization isn’t a new phenomenon.” But globalization has always been weighted to favor different cultures, polities and peoples. In Made in the Americas, which is revolutionary in bringing together art from across the Americas, the eighteenth-century material culture of North America pales in comparison to the sophistication of Central and South America. The residents of New Spain were the first to lay hands on the spoils of the luxury trade with Asia, thus subverting the ordering of the imperialist state. The great Spanish galleon ships, laden with Asian spices and furniture, thousands of ceramic vessels and lengths of textiles, travelled from Asia across the Pacific Ocean directly to Mexico. Although many objects continued their journey – travelling overland to the eastern port of Veracruz and crossing the Atlantic for Spain – a majority of the objects likely stayed in the Spanish American colonies, ornamenting the estates of the high colonial elite.[3] While Acapulco had first access to imported goods from Asia, Boston received these goods only via Europe, due to British colonial trade restrictions that persisted until the end of the War of Independence in 1783.[4] The North American Japanned furniture and embroidered textiles in the exhibition resemble a European Chinoiserie style that imagined Asian art, but had less contact with originals.

Luxury objects made in early modern Latin America cannot be cast as a Spanish variant of eighteenth-century Chinoiserie. Beneath the stylistic quotations from Asia on the surfaces lie the material and artisanal richness of the Americas.[5] While the inspiration may have come from Japan and India for a mother-of-pearl-inlaid array of boxes, desks and, improbably, paintings, these objects have a distinctly New World luminosity. Similarly, the exhibition’s pairing of a seventeenth-century embroidered Chinese wall-hanging with an contemporaneous tapestry from Peru is intended to demonstrate a transfer of Chinese design. Indeed both compositions swirl with phoenixes and bursts of peonies. Yet while the silk floss on the Chinese export textile has faded, the wool of the Peruvian textile retains the tart, saturated red of cochineal dye. A parasite that lives on cactus plants in Mexico, cochineal was one of the earliest exports from the Spanish colonies, and it eventually replaced older red dyes in Europe, Iran and Asia.[6] While these objects may bear inspirations from Asia, their material and artisanal splendor reveals why the title of the show boasts not their faithful mimicry, but their making in the Americas.

At times, though, the exhibition suggests the difficulty of communicating the multiplying absences and presences that accrued in colonial encounters. The identity and social status of the artisans who made the objects largely goes unmentioned, and, unlike in the North American section, few of the Latin American makers are named. The catalogue for the exhibition elaborates that the Spanish and Portuguese brought to the colonies not just goods, but enslaved Asian artisans who worked in Mexico City’s craft workshops. In addition to these skilled artisans, thousands more laborers from India, Southeast Asia and the Philippines were purchased in Manila and shipped on the galleons to the American colonies. The “chinos,” as they were known, worked as unpaid labor alongside indigenous workers in the textile factories of New Spain.[7] This human aspect of the Asian presence in Latin America is silent in the exhibition except in the backgrounds of the many embroideries that emulate textiles from India. It is not the South Asian style of the embroidery that signifies for the chinos, but the blank white wool and cotton textiles beneath that evoke factory labor.

The concept of global interconnectedness may date back to the age of the galleon trade, but the contours of its reality are constantly shifting. This exhibition illuminated for many museum-goers a time when “Made in China” was among the most coveted designations in the world. For art historians, the exhibition demonstrates how evidence from art objects and material culture can demand more nuanced narratives of imperialism than those provided by political and economic histories. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the colonial sites in the Spanish Americas were not only rich sources of natural resources (although they certainly were), but were also centers of manufacturing ingenuity and worldly commerce. Most importantly, not everything worked by the rule of the coin. China, Japan and India produced craft objects that Europeans desired more than anything else in the world. The gold and silver mines of the New World funded the purchase, by besotted Spanish noblemen, of items made from the humbler materials of wood, cotton, clay and shell. Though their ships could sail to any continent, Europeans in this period were comparatively provincial. And as Made in the Americas suggests, it was the outlying colonies, the far reaches of the New World, where the most productive and innovative objects of cosmopolitanism were being forged.

Sylvia Houghteling is the Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fund postdoctoral fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY

[1] Original text: “Hoy florece un célebre pintor, indio noble, llamado don José Manuel de la Cerda, que ha perfeccionado mucho esta facultad, de suerte que excede en primor y lustre a los maques de China.” See Francisco de Ajofrín, Diario del viaje que hizo a la América en el siglo XVIII el P. Fray Francisco de Ajofrín (México, Institute Cultural Hispano Mexicano, 1964). Quoted and translated in Gustavo Curiel, “Perception of the Other and the Language of ‘Chinese Mimicry’ in the Decorative Arts of New Spain,” in Donna Pierce and Ronald Otsuka, Asia & Spanish America Trans-Pacific Artistic & Cultural Exchange, 1500-1850 (Denver: Denver Art Museum, 2009), fn. 11, 34.

[2] Mitchell Codding, “The Lacquer Arts of Latin America,” in Dennis Carr, ed., Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia (Boston: MFA Publications, 2015), 85-86.

[3] Donna Pierce, “By the Boatload: Receiving and Recreating the Arts of Asia,” in Carr, ed., Made in the Americas, 55.

[4] Susan Bean, Yankee India: American Commercial and Cultural Encounters with India in the Age of Sail, 1784-1860 (Salem, Peabody Essex Museum, 2001), 27.

[5] As Gustavo Curiel writes, “Unfortunately, many of the questions that can and should be formulated concerning objects of material culture that present formal, decorative, or symbolic elements of Far Eastern origin have been replied to, a priori, by reference to another concept that only complicates the problem: the phenomenon of chinoiserie, a label proper to the French Rococo style. The effect of this label when transferred to other environments and chronologies is devastating, for it lumps together a wealth of different artistic products, irrespective of the period at which they were made, and completely fails to explain the presence of Asian elements in American artistic productions. A possibility that has still not been explored in any depth is that this presence served as scaffolding for the construction of a specific and distinct artistic language, informed by European, indigenous, and Asian traditions.” Curiel, “Perception of the Other,” in Pierce and Otsuka, eds., Asia & Spanish America, 20.

[6] Elena Phipps, Cochineal Red: The History of a Color (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2010).

[7] Donna Pierce, “By the Boatload,” in Carr, ed., Made in the Americas, 59. See also Tatiana Seijas, Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 130-140.

Cite this note as: Sylvia Houghteling, “A Lacquered Past: The Making of Asian Art in the Americas”, Journal18 (2016), https://www.journal18.org/253

Licence: CC BY-NC