Review of Portrayals from a Brush Divine – A Special Exhibition on the Tricentennial of Giuseppe Castiglione’s Arrival in China (October 6, 2015 – January 4, 2016)

On October 10, 1925, the Forbidden City in Beijing officially ceased to be the residence of the former imperial family and became the Palace Museum, with a collection that was largely formed in the eighteenth century as the personal property of the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736-1795). Born in 1711, the future emperor was still a small child when the Milanese professional painter and Jesuit lay brother Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) arrived in China in 1715 and became known by the adopted Chinese name Lang Shining. The relationship between this imperial patron and the Jesuit artist produced hundreds of paintings that can now be found in collections all over the world, but the largest concentration is still divided between the Palace Museum in Beijing and the National Palace Museum in Taipei. The National Palace Museum collection originated as a portion of the very same former imperial collection from Beijing that was shipped to Taiwan in 1948-1949 as the Nationalists retreated from the Communists during the Chinese Civil War. Today, the two museums remain separate entities, and the National Palace Museum does not loan works to its Beijing counterpart because such loans are unlikely to be returned. However, since 2009 Beijing has been repeatedly willing to lend to Taipei, and these collaborations are an important part of their shared ninetieth anniversary commemorations in Taiwan.

The blockbuster exhibition Portrayals from a Brush Divine — A Special Exhibition on the Tricentennial of Giuseppe Castiglione’s Arrival in China simultaneously celebrates the tercentenary of Castiglione’s arrival in China and the ninetieth anniversary of the National Palace Museum. Accompanied by a lavish catalogue (to which this author contributed an essay),[1] Portrayals from a Brush Divine occupied the entire suite of painting and calligraphy galleries in the west wing of the museum’s second floor. Within the multimedia gallery of that suite was a subsidiary new media exhibition, Nella lingua dell’altro: Giuseppe Castiglione – Lang Shining New Media Art Exhibition, one part of a simultaneous two-site installation divided between the National Palace Museum and the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, Italy. Combining formal exhibitions with imaginative digital animations has become a distinctive hallmark of the NPM in the last decade. Yet the paintings are what make Portrayals from a Brush Divine successful and relevant to the twenty-first century, demonstrating the extraordinary abilities of an immigrant artist whose ability to adapt allowed him to appeal to three successive Chinese emperors over more than half a century.

Encompassing a list of over one hundred objects – including paintings, porcelains, enameled metalwork, copperplate engravings, and palace memorials – the exhibition proceeds more or less chronologically through Castiglione’s work. Unprecedentedly, it opens with two monumental Christian-themed paintings in oils that were produced for the Jesuits in Genoa before Castiglione’s departure for China. Displayed in a museum for the first time, these two works are most compelling for the insights they offer into the extraordinary stylistic adaptations that Castiglione made to accommodate Qing imperial tastes. With no works from Castiglione’s first eight years in China known to have survived, the exhibition progresses directly from the early Genovese commissions to a series of unsigned ceramics painted with European styles and/or subjects using enamels during the Kangxi (r.1661-1723), Yongzheng (1723-1735), and Qianlong reigns. Scattered throughout an exhibition necessarily dominated by paintings, these vessels nonetheless enrich the checklist and serve to remind us of Castiglione’s brief time as a painter of enamels (when, it is said, he intentionally produced subpar work so as to be relieved of that tedium in order to focus on paintings). Nevertheless, his ability to replicate contemporary and earlier imperial ceramics in traditional glazes and patterns is shown in some of his earliest paintings that would be categorized in the Western tradition as still-life compositions. Here, images of imperial porcelains holding abundant plant arrangements purport to record rare auspicious natural omens, resulting in deeply inflected political paintings indicating divine approval of Yongzheng’s ascension to the Qing throne in the wake of a contested succession. The plants and flowers twist and turn in space, creating multiple opportunities to add dimensionality through tone and saturation rather than conspicuous shading or cast shadows. In an evolution of the traditional Chinese painting genre of birds-and-flowers (huaniaohua), the spectacular sixteen-leaf bird-and-flower album Immortal Blossoms in an Everlasting Spring [c. 1723-1766] demonstrates an engrossing level of detail and observation, which is only enhanced further by the surprisingly jewel-bright pigments and meticulously rendered textures.

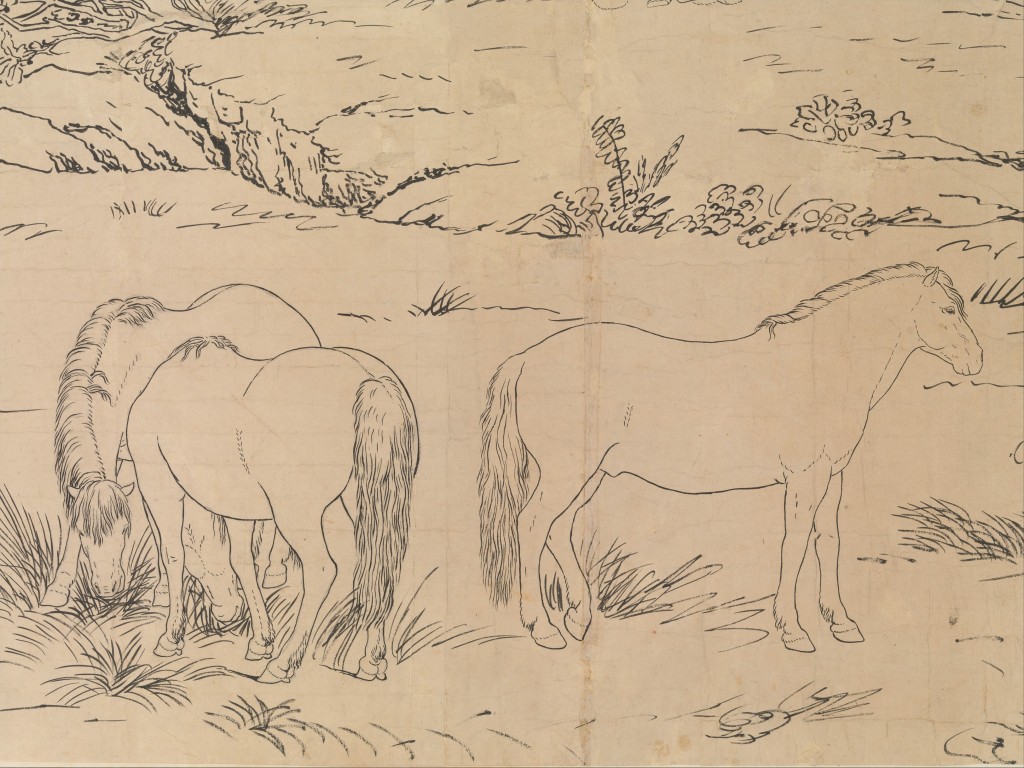

Castiglione’s ability to render the full spectrum of textures, from the mirror-smooth glaze on a porcelain vessel to the craggy bark of a gnarled pine, is seen from conception to completion in the pairing of his draft sketch and the finished work for his monumental One Hundred Horses project. Arguably the masterwork of his service for Yongzheng, the extremely rare juxtaposition of sketch and painting clearly indicates the process by which Qing court painters worked, and more importantly, the stylistic and subject changes made between versions in order to accommodate the emperor’s demands.

Detail of draft sketch for One Hundred Horses (dateable to 1723-25), handscroll, ink on paper (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Image courtesy of www.metmuseum.org.

With the shift in patron to the Qianlong emperor, the paintings become significantly larger, more overtly political, and more likely to be collaborative efforts. The show also includes a few works from other artists, including court painters who were Castiglione’s contemporaries and collaborators, and a late-nineteenth or early-twentieth-century imperial copy of the Immortal Blossoms album that serves to highlight the skill and sensitivity of the original. But despite the changes seen in the subjects, Castiglione’s ability as a portraitist—of people and of plants and animals—remains consistent throughout the exhibition. A number of sensitively rendered paintings of favorite imperial family members attest to Qianlong’s appreciation for Castiglione’s skill in rendering faces, which often included the sacred imperial visage itself. The numerous paintings of auspicious or rare birds and animals represented at (or larger than) life-size reveal that Castiglione’s abilities to depict detail were not at all limited to album leaves, and could easily be scaled up to the monumental desires of the emperor. Nearly all of these later works are accompanied by Qianlong’s imperial poems about the subjects inscribed at the top of the paintings, ensuring that his interpretation remained foremost in the viewer’s mind, whereas the paintings produced for Yongzheng are only rarely inscribed and allow the paintings to speak more for themselves.

It is these Qianlong-era paintings of birds and animals that provide most of the inspiration for the subsidiary new media exhibition that is inserted at this moment in the installation. Presented in a separate catalogue, this collaborative effort “makes good application of the freedom of 4G technology to wander around into art-making to reflect the interdisciplinary, multiculturalism, diversity, and interactive characteristics of new media art.”[2] The viewer is virtually “escorted” through this part of the show by motion-sensitive images of Qianlong and a nun, the former holding a large black-and-green imperial seal that bears a distinct resemblance to a circuit board, and the latter whose presence is both incongruous and inexplicable. Individual videos, digital animations, and theatrical light and sound installations bombard the viewer with bright motion and persistent noise. These kinds of installations are often explicitly tailored towards children, and likely offer those visitors an exciting intermission. However, considering the repeated emptiness of this space in comparison with all the other galleries, the vast majority of visitors seemed to prefer the silent elegance of the original paintings to their digital reinterpretations.

The National Palace Museum’s first 4K animation: Adventures of the Mythical Creatures at the National Palace Museum

The aggressiveness of the new media installation cast the subtlety of the exhibition’s concluding objects into sharp relief. In 1764, only two years before his death, Castiglione and the three other missionary painters then attached to the court were instructed to draft sketches of battles in Qianlong’s successful but brutal 1755-1759 campaigns quelling Dzungar Mongol and Muslim Khoja rebellions in what is now Xinjiang province. The sketches were sent to France to be reproduced by Charles-Nicolas Cochin and Jacques Philippe Le Bas as copperplate engravings, and the finished French set is presented alongside two rare galley proofs and a number of official documents about the original events, the printing process, and Castiglione himself. Considering the bright colors that otherwise characterize both the exhibition and eighteenth-century Qing court painting in general, concluding with these grisaille prints creates a somber, quiet end that also served to reflect Castiglione’s death in 1766, soon after the sketches were dispatched to Europe.

It is significant that a European Qing court painter was chosen as the topic of a monographic exhibition produced as part of the nonagintennial celebrations of the National Palace Museum. Although the Qing court and the Qianlong emperor have dominated both its exhibitions in Taipei as well as traveling exhibitions curated by the Palace Museum in Beijing for decades, a show of this magnitude dedicated to Castiglione reflects his continued appeal to diverse audiences as well as his relevance in the fully global and digital twenty-first century. It is perhaps more significant that the anniversary celebrations began with Portrayals from a Brush Divine rather than what succeeds it in the same galleries: Synthesis and Departure in Tradition: Painting, Calligraphy, and Dong Qichang (1555-1636) (January 9 – March 29, 2016). Dong was an extraordinarily influential Ming painter and painting theorist who continued to define the practice and teaching of Chinese painting for centuries after his death. This exhibition will be far more traditional and linear than Portrayals from a Brush Divine: “to clearly present the progression of Dong’s art and ideas, the exhibit revolves around his numerous dated works, presenting them chronologically as much as possible to provide viewers with a better understanding of his life and artistic accomplishments.”[3] In contrast, the chronological treatment of Castiglione’s works in Portrayals from a Brush Divine communicates more about the Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors than Castiglione himself, and details of his life remain elusive despite the wealth of extant paintings.

Most scholars of Chinese painting would likely consider Giuseppe Castiglione and Dong Qichang as polar opposites, artists whose works speak to the binary distinctions that many Chinese made between European and Chinese painting in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[4] And it is only now, thanks to the very recent acceptance of the Qing dynasty as a period worthy of study and a separate wave of interest in early modern global exchanges, that a Qing court painter could even have been considered for such an exhibition. That an eighteenth-century court painter — and a European one, at that — was chosen to inaugurate the National Palace Museum’s 90th anniversary celebrations reflects just how much the field of Chinese painting has changed since the museum was founded in 1925.

Kristina Kleutghen is David W. Mesker Career Development Professor of Art History and Assistant Professor of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis

[1] He Chuanxin, ed., Portrayals from a Brush Divine: A Special Exhibition on the Tricentennial of Giuseppe Castiglione’s Arrival in China (Taipei: National Palace Museum, 2015).

[2] National Palace Museum, Taipei, “Paintings Come Alive: New Media Installations Inspired by Giuseppe Castiglione’s Works,” accessed December 31, 2015, http://theme.npm.edu.tw/exh104/langshining/taipei/en/page-2.html#main.

[3] National Palace Museum, Taipei, “Introduction,” Synthesis and Departure in Tradition: Painting, Calligraphy, and Dong Qichang (1555-1636), accessed January 18, 2016, http://theme.npm.edu.tw/exh105/dongqichang/en/index.html.

[4] Martin J. Powers, “The Cultural Politics of the Brushstroke,” Art Bulletin 45, no. 2 (June 2013): 312–27.

Cite this note as: Kristina Kleutghen, “Castiglione and China: Marking Anniversaries”, Journal18 (2016), https://www.journal18.org/271

Licence: CC BY-NC