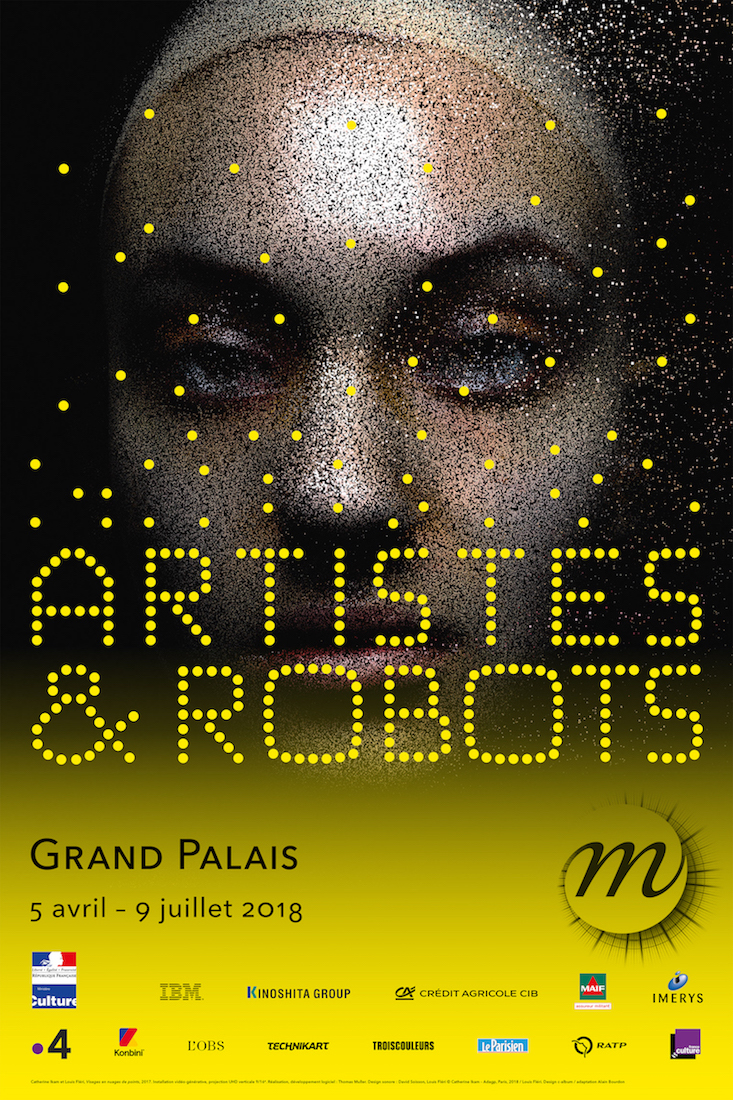

Artists & Robots is at the Grand Palais in Paris from April 5 to July 19, 2018. It is accompanied by the catalogue Artistes & Robots, ed. Laurence Bertrand Dorléac et Jérôme Neutres (Paris : Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2018)

Artists & Robots, an exhibition currently on view at the Grand Palais, is designed to be a crowd pleaser. The exhibition is billed as the first ever dedicated to “artificial imagination” defined as a “generic term used to group together robotic, generative and algorithmic art.” [1] One can easily imagine the desire of the curators, Laurence Bertrand Dorléac et Jérôme Neutres, to appeal to a broad audience eager to learn about robotics in an increasingly digitized modern art world. A smaller selection of works first appeared at the Astana Expo 2017, the World Fair at Kazakhstan, where Bertrand Dorléac and Neutres explored the theme in a vast exhibition space destined for a very diverse public. In Paris, they expanded the number of artists and edited a series of videos, strategically placed in the exhibition, that encouraged visitors to question artistic creativity at a time when robots increasingly co-exist and interact with human agency.

While it may seem incongruous to review an exhibition dedicated to twenty-first century robotics in Journal18, in fact, even before Jacques Vaucanson’s display of three automata—a defecating duck, a pipe and tabor player, and a flute player—at the Hôtel de Longueville in 1737, issues of creativity and mechanical reproduction fascinated the eighteenth-century art world. As Jessica Rifkin has perspicaciously argued, Vaucanson’s automates engaged with philosophical questions about life processes and artificial intelligence, issues that resurface in Artists & Robots.[2]

The exhibition is divided into three sections. The first, entitled “Machines to Create,” focuses on how artists put together robots to paint, dance or produce music, not unlike their eighteenth-century precursors. The second section, “The Programmed Work,” suggests that as robotic machines disappear, they are nonetheless visible as computer codes on screens. A subtheme proposes that “in fact, robots are becoming so autonomous that they appear to challenge the authority of the artist who delegates part of their power to the machine,” a rather frightening concept that seems geared more toward science fiction than contemporary aesthetics. The third section, entitled “The Robot Emancipates Itself,” shows how artists seek to question and manipulate artificial intelligence. Before examining specific works, it is useful to cite the questions that the curators put forth as their guiding conceit: “What can a robot do that an artist cannot? If it has artificial intelligence, does a robot have an imagination? Who decides: the artist, the engineer, the robot, the spectator or everyone together? What is a work of art? Should we fear robots? Artists? Artist-robots?”

Fig. 1. Nam June Paik, Olympe de Gouges, 1989. Mixed media. Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, gift of the artist in 1989 in memory of Dany Bloch. Photo © Nam June Paik Estate/photo Eric Emo/Musée d’Art Moderne de la ville de Paris/Roger-Viollet.

Nam June Paik’s Olympe de Gouges (1989) (Fig. 1) opens the show in juxtaposition to Jean Tinguely’s Méta-Matic no. 6 (1959) and Nicolas Schöffer’s CYSP 1 (1956) cybernetic sculpture. Paik’s twelve TVs crowned with a bouquet of synthetic flowers certainly introduces visitors to how artists appropriate machines to create new works. However, the artist’s subtler engagement with the legacy of Olympe de Gouges, a leading female activist during the French Revolution, remains latent but unexplored throughout: where are the women artists? Is there a space for a feminized robot? Or cyberfeministes?

Fig. 2. Patrick Tresset, Human Study #2.d La Grande Vanité au corbeau et au renard, 2004-2017. Three robots, a stuffed fox and raven, drawings on paper. Photo © Aldo Paredes for Rmn-Grand Palais, 2018

In the following room in the same section, Patrick Tresset’s Human Study #2.d La Grande Vanité au corbeau et au renard (2004-2017) (Fig. 2) is inspired by Jean de la Fontaine’s fable: a taxidermized fox and crow are strategically placed on either side of a human skull. At the same time, three robotic arms are attached to school desks and produce drawings after a still life. The repetitive computer-generated drawings are in turn mounted into a wall display. An earlier version of this piece was shown at the Astana venue, where Tresset focused solely on the human skull; the inclusion of the fox and the crow was presumably meant to appeal to the French audience. The classic reference to flattery as a form of imitation suggests Tresset is questioning how the art market impacts individual creativity. At the same time, the work is a sensitive questioning of how we assess the artist’s presence as part of the creative process, recalling a central tenet of eighteenth-century art criticism.

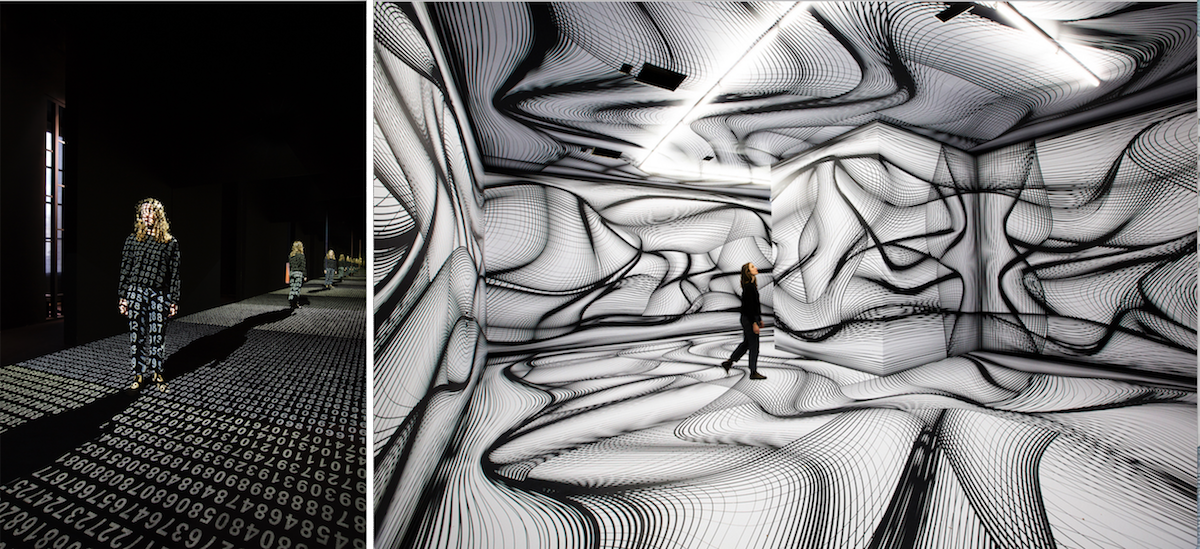

LEFT: Fig. 3. Raquel Kogan, Reflexão #2, 2005. Interactive installation, custom software, mirrors and projection, variable dimensions. Photo © Aldo Paredes for Rmn-Grand Palais, 2018

RIGHT: Fig. 4. Peter Kogler, Untitled, 2018. Digital impression on vinyl, variable dimensions. Photo © Aldo Paredes for Rmn-Grand Palais, 2018

Raquel Kogan and Peter Kogler’s contributions explore how computer generated images can provoke disorientation, a theme that also engages eighteenth-century art insofar as it recalls the spatial dynamics of rococo interiors. In Kogan’s piece the interior is a black box animated by streams of code that are projected and reflected on mirrors (Fig. 3). Visitors enter the cube and their own bodies are covered in code. Kogan’s Reflexão #2 (2005) is one of the most popular and interactive works in the show; however, this play with mirrors actually demonstrates how the curators have marginalized discourses by a range of digital artists, who have been exploring the augmented body—both hyper-connected and commodified—for the past twenty years. Peter Kogler’s Untitled (2018), a computer-generated spiral wall paper that was applied to the floor, walls and ceilings similarly confuses the visitor’s spatial orientation (Fig. 4). The black-on-white curvilinear lines and elongated s-curves recall eighteenth-century garden plans, notably the over 400 images of ornamental s-curves published by Georges-Louis Le Rouge in his notebooks of jardin-anglo chinois prints. This reference is further enhanced by the fact that as one progresses through the two rooms, one seems to be caught in a rococo garden labyrinth.

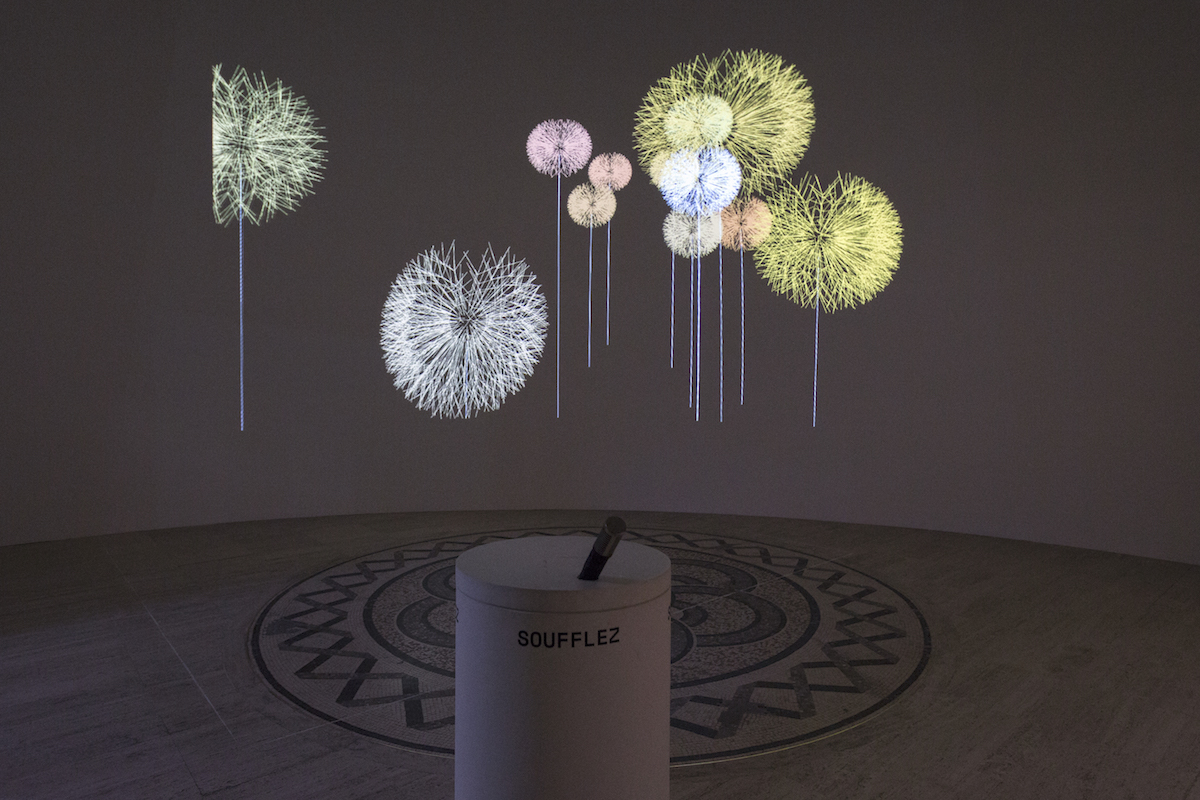

Fig. 5 Edmond Couchot and Michel Bret, Les Pissenlits, 1990-2017. Variable projection systems. Photo © Aldo Paredes for Rmn-Grand Palais, 2018

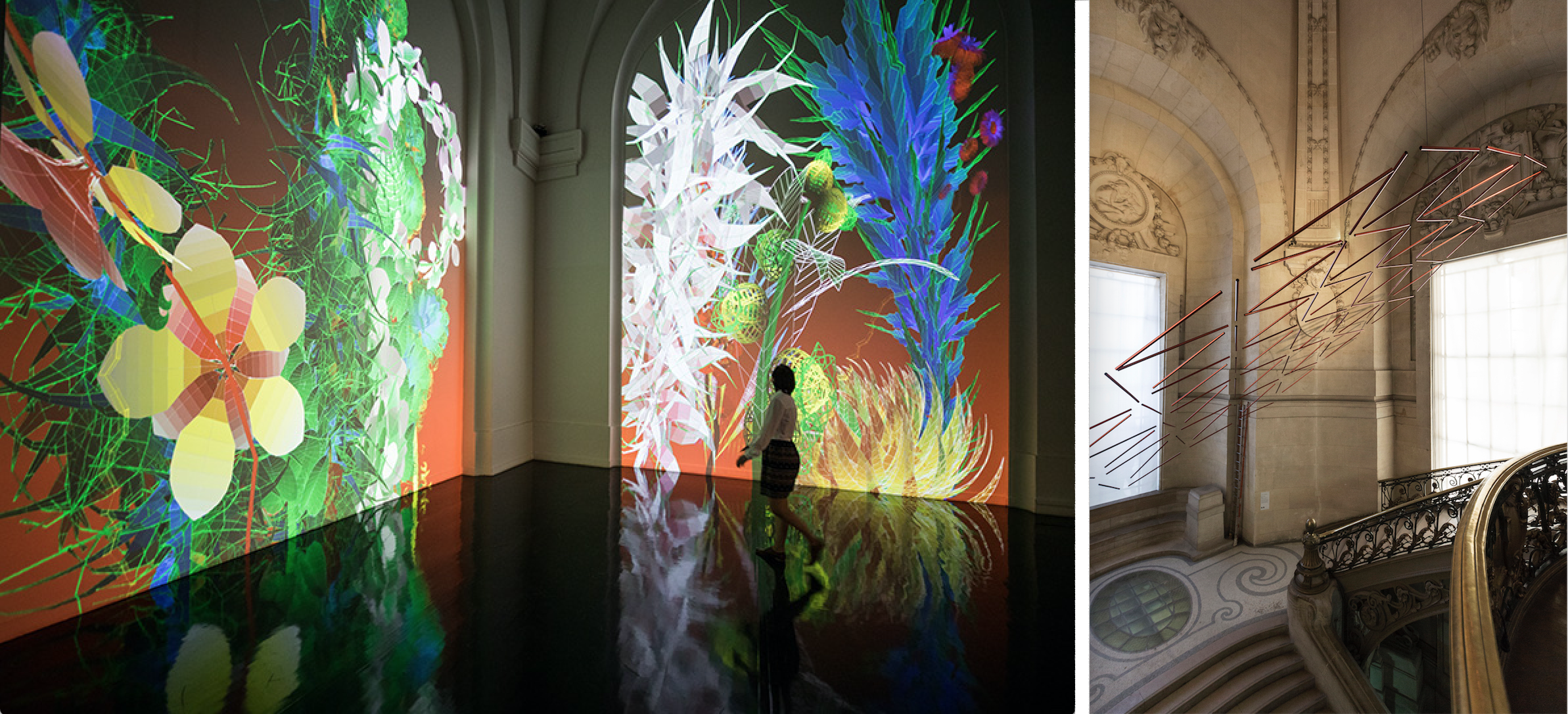

While many works in Artists & Robots explore mechanical processes, several artists turn to the natural sciences, recalling prolific studies by eighteenth-century botanists. Edmond Couchot and Michel Bret’s Les Pissenlits (1990-2017) and Miguel Chevalier’s Extra-Natural (2018) both challenge how we think about plants as species and in the natural world. In Les Pissenlits, visitors are invited to blow air into a sensor that then explodes the electronically generated flowers, creating pixelated blooms that re-enact pollination (Fig. 5). The ability to create with nature is echoed in Chevalier’s vibrantly colored plants projected onto two joined screens (Fig. 6). They respond to sensors that capture visitor’s movements and that, in turn, animate the plants. As the artistic advisor for the exhibition, Chevalier has effectively created new ‘species’ that question how we categorize plants and art. We can also imagine enlightenment mathematicians like Gaspard Monge being entranced by Elias Crespin’s deconstruction of one of nature’s most common geometric forms, the hexagon, which was observed in bee hives or snowflakes but is here is reconstructed in the Grand HexaNet (2018), a piece commissioned for the Grand Palais (Fig. 7). Crespin mounted 90 cylinders of interlocked triangles suspended above one of the grand staircases, where the tubes seem magically to scatter and recombine, forcing contemplation of mathematical games, a pastime common to eighteenth-century entertainments.

LEFT : Fig. 6 Miguel Chevalier, Extra-Natural, 2018. Generative and interactive virtual reality software. Software : Cyrille Henry & Antoine Villeret Technical production : Voxels Productions. Courtesy Lélia Mordoch, Paris/Miami. Photo © Nicolas Gaudelet © Adagp, Paris 2018

RIGHT: Fig. 7. Elias Crespin, Grand HexaNet, 2018. 90 cylinders of anodized aluminum, nylon, motors, electronic interface. Photo © Aldo Paredes for Rmn-Grand Palais, 2018

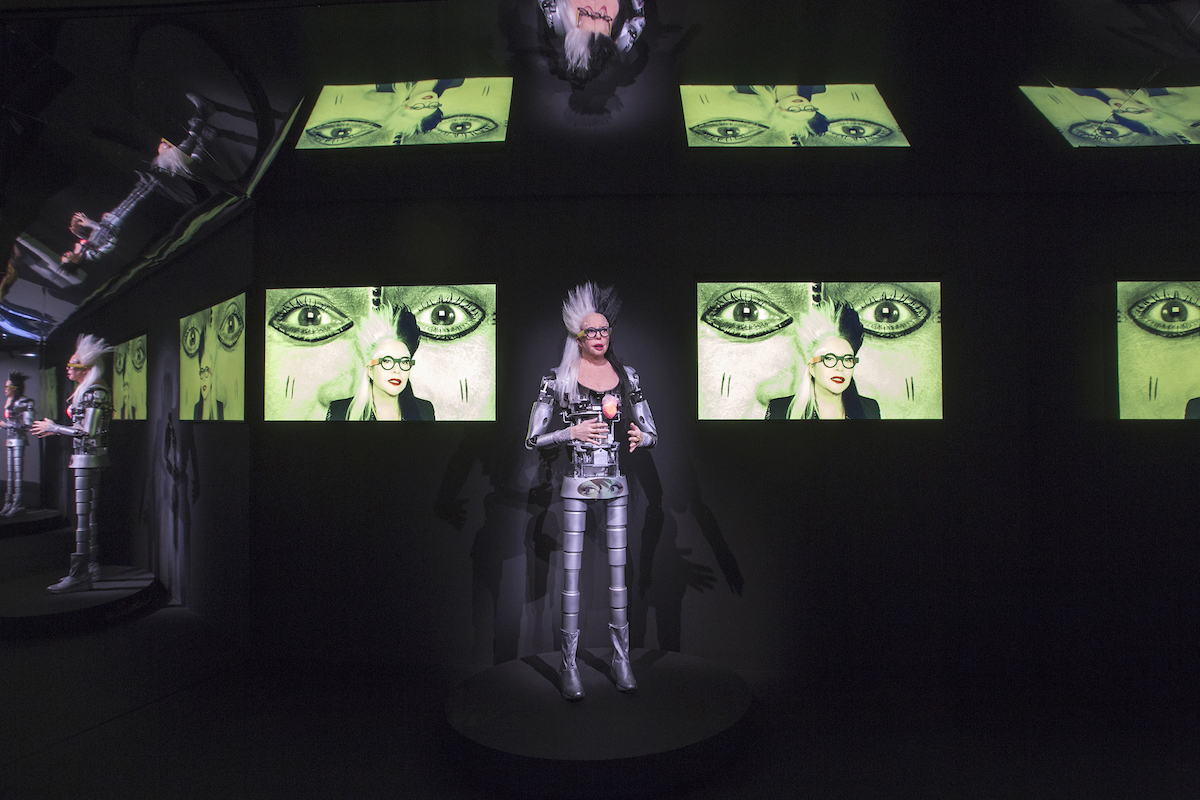

Vaucauson’s automata seem to rematerialize in the final section, dominated by two avatars: Orlan’s Orlan et Orlanoïde, Strip-tease électronique et verbal (2017), commissioned for the show, and Takashi Murakami’s Sans titre (2016). Murakami’s life size representation of himself as one of the enlightened figures of the Arhat Buddhist tradition is immobile, but three sets of moving eyes capture the viewer as the android recites the Sūtra du Coeur. In Orlan’s work, videos of the artist question her android, whose head is a self-portrait while the body, a transparent veil over mechanical parts, is transformed into a machine (Fig. 8). These modern androids call to mind how Julien Offray de la Mettrie’s L’Homme machine (1747) and Étienne Bonnot de Condillac’s Traité des sensations (1754) polarized Enlightenment philosophy’s attempts to grapple with similar questions about the human body, imagination, and autonomous agency.

Fig. 8 Orlan, ORLAN ET ORLANOÏDE, Strip-tease électronique et verbal, 2017. Mixed media. Photo © Aldo Paredes for Rmn-Grand Palais, 2018

While the dialogue posed between Artists & Robots will animate contemporary art for years to come, the rather narrow focus of the exhibition implies that the digital arts can be separated from debates about man and machine. By attempting to place artists at the cutting edge of the robotic field, the Grand Palais exhibition actually limits rather than expands the rich and evolving fields of digital arts, subjects that a thriving community of artists, hackers, and media art critics have been addressing for many years.[3] By comparison, the “Hello Robot. Design between Human and Machine” exhibition, which was curated by Amelie Klein, Thomas Geisler and Marlies Wirth and opened at the Vitra Design Museum in 2017, represents a thoughtful alternative approach to “artificial imagination,” suggesting how designers contend with the hopes and fears about robotics. Perhaps Vaucanson’s automata serve as a cautionary tale, providing a visualization of mechanical processes that stimulated debates about how we define humanity. This exhibition’s emphasis on robotic art restricts rather than opens the debates that Vaucanson initiated.

[1] Quoted from the Artists & Robots Exhibition Guide (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2018), n.p.

[2] Jessica Riskin, “Eighteenth-Century Wetware,” Representations 83:1 (Summer 2003), 97-125; and Riskin, ‘‘The Defecating Duck, Or, The Ambiguous Origins of Artificial Life,’’ Critical Inquiry 29:4 (Summer 2003), 599-633.

[3] See, for example, Culture(s) numérique(s) (Centre des arts d’Enghien-les-Bains et l’Institut Français, 2012), http://www.cda95.fr/fr/content/cultures-numeriques.

Cite this note as: Susan Taylor Leduc, “Artists & Robots: A Review,” Journal18 (July 2018), https://www.journal18.org/2759.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.