Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800: Maurice-Quentin de La Tour (1704–1788) website, 2021 edition, http://www.pastellists.com/LaTour.htm.

French pastellist Maurice-Quentin de La Tour (1704-1788), whose sitters included Madame de Pompadour, Jean Le Rond d’Alembert, and Voltaire, is often and justifiably lauded as a “tour de force.”[1] Neil Jeffares, the author of a La Tour catalogue raisonné that is freely available online, should likewise be regarded as a force to be reckoned with.

Jeffares, an art historian who entered the field following a long career as a financier, has devoted well over fifteen years to his dictionary of pastels and pastellists. The La Tour catalogue, launched in 2020, constitutes Jeffares’s most recent and most comprehensive addition to this compendium. It is also the first catalogue raisonné on La Tour to be undertaken since 1928.[2] While the dictionary began as a printed book published in 2006,[3] the online version of this thorough contribution to the field constitutes a much-expanded iteration of the original print publication, though it largely retains the layout of the 2006 tome.

The online catalogue, which Jeffares routinely updates to reflect new research, is an indispensable resource for anyone keen on learning more about La Tour and for drawing new audiences to his work. At the same time, Jeffares’s perpetuation of the print book format, his reliance on alphabetical organization, and his persistent use of individual PDFs for each of the catalogue’s subsections hint at his own and some of his prospective readers’ continued comfort with old-school, hard-copy catalogues.[4]

The first PDF is an introduction to La Tour’s life and oeuvre. Here and throughout, Jeffares expertly consolidates and critically assesses the primary sources that he has scoured. In his catalogue entries, however, he often opts not to rehash the arguments presented by authors of the secondary sources to which he alludes. Readers are thus required to revisit these earlier texts on their own in the interest of getting up to speed. Parts of Jeffares’s introductory text, including its in-depth study of the many spellings of La Tour’s name, for instance, teem with minute details, which are impressive and exhaustive, if sometimes overwhelming. The forty-two-page introduction’s thirty-nine sub-subheadings are grounding, handy, and telling of the considerable exertion that is essential to the catalogue’s ongoing creation and, crucially, its use. Casual readers: be forewarned.

Jeffares’s essay on La Tour’s life and work is followed by the meat of the catalogue, which is divided into six separate parts/PDFs. The first of these parts/PDFs is devoted to self-portraits, the second through fifth parts/PDFs include named sitters who are organized alphabetically, and the sixth part/PDF includes unidentified sitters. Jeffares explains that the difficulty of dating La Tour’s pastels prompted him to arrange the catalogue in accordance with sitters’ names rather than the works’ chronology. His reticence with regard to the often-unresolved order in which La Tour made his many studies of a single sitter, as well as his reservations about works that he considers to be (and, in some cases, has personally identified as) copies after La Tour, also contributed to his choice of organizational framework. Readers with a particular interest in tracing the artist’s oeuvre over time will, however, be pleased to find an illustrated “chronological arrangement of dated or datable pastels” among the several supplemental materials that are hyperlinked on the catalogue’s home page.

Other supplementary PDFs that are easily accessible through the catalogue’s preface page include but are not limited to a chronological table of documents relating to La Tour and a compendium of criticism that spans the eighteenth through twenty-first centuries.[5] Twelve in-depth essays about specific portraits, which Jeffares asserts merit more attention than can be afforded by brief catalogue entries, also appear here. These essays often feature discoveries that Jeffares has made himself, sometimes with help from other scholars. They also outline the painstaking detective work that he has shouldered in the service of his conclusions, albeit in a colloquial tone that, while accessible, sometimes undermines the seriousness of his undertaking.

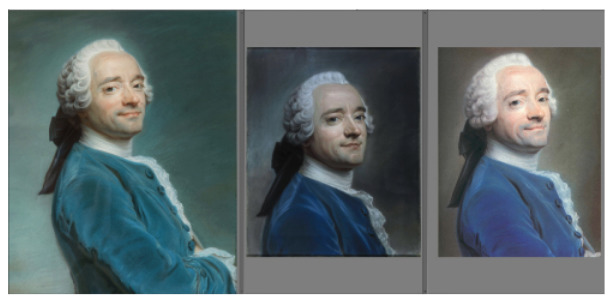

The works are listed in their respective online collection databases as, from left to right: La Tour, Autoportrait au jabot de dentelle, 1750. Pastel, 64.5 x 53.5 cm. Musée de Picardie, Amiens; La Tour, Self-Portrait with Lace Jabot, c. 1750. Pastel on paper, 45 x 37 cm. Musée Cognacq-Jay, Paris; La Tour, Self-Portrait, 1764. Pastel on paper, 45.7 x 38.1 cm. Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena.

The extended essay entitled “La Tour, Autoportrait au jabot” presents primary and secondary sources that Jeffares consulted, and it uses comparative analysis to posit a rather controversial argument about La Tour’s arguably most recognizable self-portrait, versions of which are in the collections of the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, the Musée Cognacq-Jay in Paris, and the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (Fig. 1). Jeffares asserts that the pastel in Amiens, long considered to be the definitive autograph version of this self-portrait, is actually a copy by Jean-Gabriel Montjoie (1725-1800), one of La Tour’s students, while the Cognacq-Jay version is a strong autograph replica of a “now lost or destroyed” La Tour original, and the Norton Simon version is either a “weaker” autograph replica or a copy by someone else.[6] Jeffares acknowledges that he has not yet examined the Norton Simon pastel in person, an admission that is at once admirable in its honesty and somewhat disconcerting. But who can be expected to have examined everything in a publication of this scope, especially now?[7] The far more succinct catalogue entry devoted to these and other versions of the Autoportrait au jabot summarizes this argument after pushing up against the suggestions put forth by previous scholars whose publications are fleetingly mentioned but whose actual arguments aren’t sufficiently outlined. Readers are thus obliged to refer to the extended essay and the many sources it mentions and, in some cases, contradicts in order to fully understand (much less assess the merit of) Jeffares’s position.

Given its availability online, consulting Jeffares’s extended essay on the Autoportrait au jabot in tandem with his online catalogue entry wouldn’t seem too troublesome a task were it not for the fact that the catalogue entry does not actually include a hyperlink to the extended essay on the same group of portraits. Instead, the entry twice includes the same hyperlink to a 2019 blog post about this group of pastels on the author’s personal website that is actually identical to the extended essay, barring its layout. Ironically, those interested in getting on the same page as Jeffares often have to leave the page on which an object of interest is featured to access and cross-reference other hyperlinked texts within the larger dictionary of pastels and pastellistsand/or on Jeffares’s personal website. Even if readers are of a mind to embrace this exercise in excavation by delving into the hyperlinked texts (not to mention scouting out other references that may be unavailable online), getting back to where they started can be complicated, as hitting the back button—the only way of returning to the catalogue entry—automatically takes them back to the beginning of the PDF in which the entry is included, not the page where they left off. Readers must thus keep the page in the original PDF in mind or, alternatively, be prepared to open different PDFs from the catalogue in different tabs in order to toggle between them more efficiently.

A similarly cumbersome process is required of researchers interested in using the dictionary’s search function (unfortunately, one cannot search the La Tour catalogue alone). They must search for a keyword, date, sitter, etc. to yield a list of PDFs in which the term appears and then initiate a separate search within each document using the Control+F/Command+F function. This complicated process is compounded by the catalogue’s double-decimal numbering system, its compressed formatting, its unusual placement of images after each main entry, its entries’ confusing way of referring to different illustrated and unillustrated versions of a portrait without clearly identifying which one is which, and its many symbols and shorthand notations that are impenetrable without careful study of the six single-spaced pages devoted to the dictionary’s internal system of abbreviations. During the time it takes to become proficient in these symbols, the PDF where the search began may well have been updated by the author whose unwavering commitment to comprehensiveness sometimes supersedes comprehensibility. The author’s routine alterations and researchers’ required reexamination of interrelated and often-updated PDFs by way of periodically returning to the website (toggling each time) cement the catalogue’s status as something of a moving target—a rapidly changing reference text whose PDFs, like the pastels that they feature, are fugitive.

Having just spent several years working through hundreds of portraits by another eighteenth-century artist called Carmontelle (1717-1806), I am beyond sympathetic to the daunting challenge of contending with centuries’ worth of scholarship that reproduces tangled and sometimes erroneous information. I know too well the urge to put everything on paper (or in a PDF, as it were) in the name of making years of work available to people who haven’t spent chunks of their lives steeped in the mountain of material at hand. Jeffares’s text operates as a fixative for a corpus of unstable archival materials in much the same way as an actual fixative helps to preserve a pastel. But if usability determines usefulness, suffice it to say that this online catalogue isn’t the most user-friendly.

But Jeffares’s catalogue is written in the spirit of comradery and generosity, as is made evident by the supplemental PDF entitled “Maurice-Quentin de La Tour’s family.” This PDF—a consolidation of four blog posts on the author’s personal website—is refreshing, not only because it features actual photographs of the archival documents that Jeffares consulted and details the many steps that he took in order to answer minute questions related to La Tour’s family history, but also because it includes the author’s admittance of his own fallibility and his candid call for collaborators:

Some of my transcriptions contain errors for reasons which will be obvious from the images above: I shall of course be grateful for corrections, and also for any further documents which relate to La Tour or his pictures. Actually let me rephrase that: I shall be genuinely pleased to be told of the mistakes in my clumsy attempts to render these documents into something a computer can cope with, and I shall be thrilled if anyone can direct me to what I’ve missed. There must be invoices and bills and other material out there which I’m not going to come across without your help, and I hope that the sight of these examples will make you share my enthusiasm for gathering them together.[8]

Jeffares’s attempt at crowdsourcing is conveyed with disarming candor; he clearly lives with La Tour in a manner that seems to be unmatched, unencumbered by constraints, pressures, and responsibilities that come with institutional affiliations, and uninhibited by any need to claim La Tour scholarship as his exclusive domain. Learning about La Tour and disseminating this still-expanding knowledge in real time are the author’s top priorities.

I admire the voracity, tenacity, and meticulousness with which Jeffares has undertaken this La Tour catalogue and the historiographic, archival, and connoisseurial work on which it is predicated. Provided that researchers are prepared to take the time to familiarize themselves with Jeffares’s idiosyncratic notation system and to commit to exploring and critically assessing the text and the embedded hyperlinks associated with the works of art that are most pertinent for their purposes, their efforts are sure to be rewarded.

To some, a comprehensive compendium of a single artist’s oeuvre may seem out of step in an age when cross-cultural connections, be they engendered by choice or by force, are the field’s focus. Jeffares may not engage in this discourse or, for that matter, in a discussion of eighteenth-century portraiture, though the dictionary of which the La Tour catalogue forms a part does invite comparison across pastellists. But Jeffares’s cross-linked PDFs create an internal web of sitters, portraits, patrons, archival documents, etc., and his keen connoisseurial eye and comparative analyses, particularly when applied to what he believes to be autograph replicas (see Fig. 1), seek to clarify connections across works and, in so doing, to distinguish the distinctive techniques that make a La Tour a La Tour. His text seems both dated and timeless in its insistence upon a single artist’s self-contained corpus and in its mutability. Because establishing an artist’s corpus remains fundamental to the field of art history, researchers should be beyond grateful for Jeffares’s expert archival legwork in its function as both a means and an end.

Margot Bernstein is a Lecturer in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University, NY

[1] James Gardner, “A Tour de Force, Honest and Engaging,” The Wall Street Journal, June 4, 2011, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303657404576359690919393166.

[2] Paul Albert Besnard and Georges Wildenstein, La Tour: La vie et l’oeuvre de l’artiste (Paris: Les Beaux-arts, édition d’études et de documents, 1928).

[3] Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800 (London: Unicorn Press, 2006).

[4] In a roughly thirty-two-minute YouTube tutorial on how to navigate his online La Tour catalogue (and, by extension, the Pastels and Pastellists website), Jeffares jokingly remarks that this video is “if you like, a Janet and John explanation of how to find material in the website. If you know who Janet and John are, you probably need this film; if you don’t, that means you’re younger than I am, and you may well be able to work your way around the website intuitively.” Jeffares also created a video in which he introduces La Tour and summarizes some of the discoveries discussed in the catalogue. Both videos are hyperlinked on the La Tour catalogue’s preface page. See Jeffares, “Pastellists La Tour Guide,” March 27, 2021, video, 2:09, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dpYIC5RodQ; “La Tour and the Smile of Reason,” May 10, 2021, video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JXb1SVsTlxE.

[5] Jeffares has transcribed but has not translated these documents, nor any other French-language passages, throughout the catalogue.

[6] Jeffares, “La Tour, Part I: Autoportraits,” PDF updated April 27, 2022, Pastels & Pastellists website, 8, http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/LaTour1.pdf; Jeffares, “La Tour, Autoportrait au jabot,” PDF updated August 6, 2021, Pastels & Pastellists website, http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/LaTour_Auto_jabot.pdf.

[7] Jeffares, “La Tour, Autoportrait au jabot.”

[8] Jeffares, “Maurice-Quentin de La Tour’s family,” PDF updated November 1, 2016, Pastels & Pastellists website, 6, http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/LaTour_Family.pdf.

Cite this note as: Margot Bernstein, “Maurice-Quentin de La Tour: A Review” Journal18 (June 2022), https://www.journal18.org/6376.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.