On March 1, 1720, the London theater entrepreneur and critic Richard Steele wrote of an opera rehearsal in an essay for his journal The Theatre: “At the Rehearsal on Friday last, Signor Nihilini Beneditti rose half a Note above his Pitch formerly known. Opera Stock [climbed] from 83 and a half, when he began; [closed] at 90 when he ended.”[1] The “Opera” here refers to the newly founded Royal Academy of Music, an opera company incorporated as a joint-stock enterprise [2] akin to the South Sea Company, inciter of the eponymous “South Sea Bubble.” Underwritten by a group of seventy-three wealthy aristocrats, the company ushered in a new form of musical patronage distributed among those entrepreneurial shareholders. Among them were dozens of investors in the South Sea Company including James Craggs the Younger, secretary of state, Matthew Decker, former governor of the Company, and many members of the landed gentry such as the Dukes of Chandos and Newcastle. Equally willing to sink money into the musical venture, some of them pledged £200 or more to obtain a voting share that would allow them to be personally involved in the decision-making of the company’s business: putting on Italian operas. At the time of the Academy’s incorporation, its sister enterprise’s South Sea share price was on a steep climb towards its eventual dizzying height mere months before the market crashed.

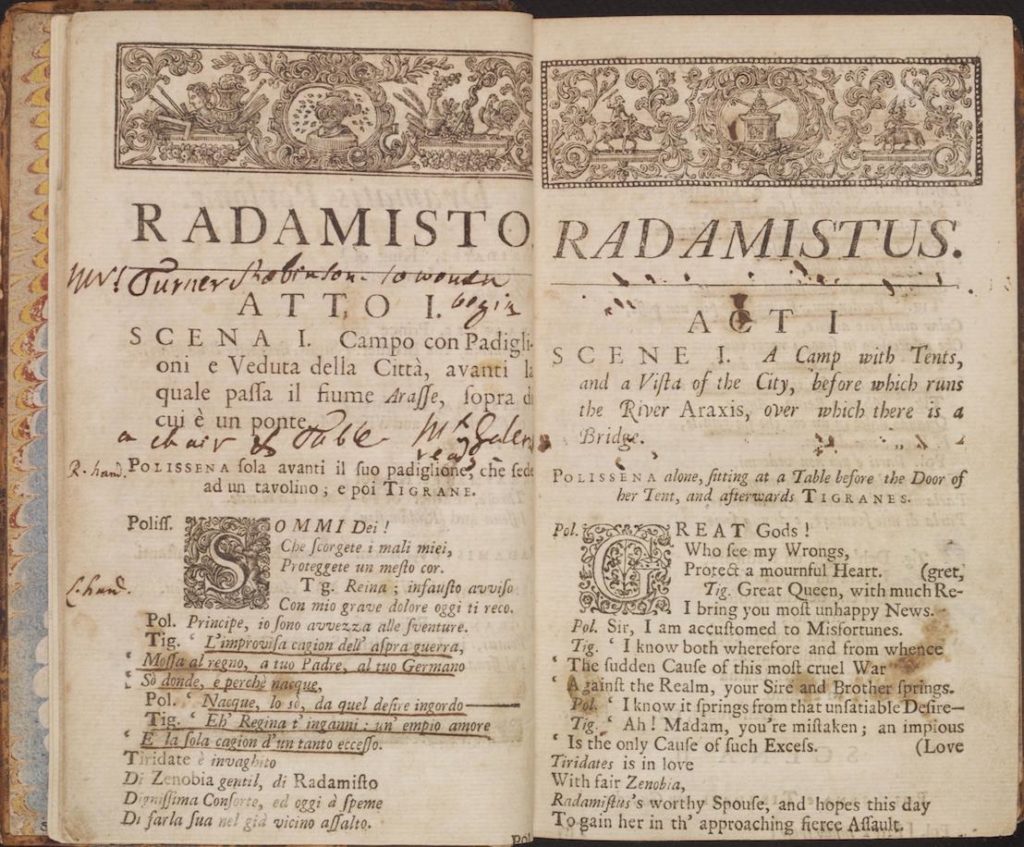

The performance Steele heard—assuming he indeed attended the rehearsal himself—would have been led by George Frederick Handel, another well-known investor in the South Sea Company. Recently made “Master of the Orchestra,” Handel had assembled his band of instrumentalists and singers in preparation for the two operas that would open the Academy’s inaugural season: Numitor by Giovanni Porta and Radamisto by Handel himself.[3] Of the original cast of these two season openers, Steele specifically singled out the castrato Benedetto Baldassari,[4] albeit with a fictive name, to show the market-shifting power of high-pitched virtuosity. It should not be a surprise because artificially produced, full-throated male sopranos were the headliners of Italian opera, a foreign import which had begun to dominate London’s theater scene. The superhuman techniques they purportedly possessed—exquisite breath control, range, agility, finesse, and so on—encouraged composers to write highly challenging arias that would send the hearts of the English audience racing and the market, as Steele saw it, into a frenzy. Sung by Baldassari, the aria “Deh, fuggi un traditore”[5] from Handel’s Radamisto (Fig. 1) was just one such example.

Castrati were both sensational attractions for those keen on fashionable entertainment and targets of criticism for those repulsed by the unsettling taste they represented: effeminate, lavish, and foreign.[6] Steele certainly belonged to the latter category, as the satirical nature of his comparing an aria to speculative fervor suggests. Moreover, the nickname he chose for the castrato, “Nihillini,” was perhaps a forewarning of the frothy nothingness those stock certificates would soon become. All ridicule notwithstanding, Steele’s comparison remains a telling example of music’s role in the time of the 1720 bubbles: it reveals a sensuous dimension of financial speculation such that psychic rewards from musical entertainment and monetary profits from investing become comparable. Thus, the burgeoning yet precarious financial markets in metropolises across Europe were rendered audible, and such “market music” was not only heard in theaters but also seen in print, performed at private gatherings, and consumed at home.

In the same year, another bubble known as the Mississippi Bubble was brewing across the channel in France. The Mississippi scheme, a credit system masterminded by the Scottish financier John Law, led to a debilitating bank run. It not only bankrupted many but caused a deadly stampede on rue Quincampoix, where creditors, investors, and brokers flocked to the Mississippi Company’s headquarters to redeem their soon-to-be-worthless scrip. Both capturing and caricaturing the devastating experience of financial speculators during this run, Francois Couperin wrote a five-voice canon entitled “Les agioteurs au désespoir.” In the extant copy of the canon, all five voices are notated in tenor clefs, likely suggesting the voices of five stockjobbing men grieving their loss of fortune.[7] The text begins with “pleurez, pleurez, mes tristes yeux,” an opening gambit for lament frequently found in French verse of the time:[8]

Pleurez, pleurez,

mes tristes yeux, mes tristes yeux:

fortune hélas! tu me flattois:

mais, pour me mieux trahir

fautil rentrer dans le néant de mes aveux;

quel sort fatal!

ah, quel supplice;

oh, Dieux! trop justes Dieux!

que mes accents et que mes plaintes pénètrent jusqu’aux Cieux!

[Weep, weep,

My dreary eyes, my dreary eyes.

Fortune, alas! You flattered me,

but it’s best to betray me,

for I must retreat into the emptiness of my confessions.

What ruinous fate!

Ah, what a torment!

Oh, gods! Ye righteous gods!

May my words and wails penetrate to heaven!][9]

While the stockjobbers’ sorrow, anger, and despondency culminate in a blasphemous moan in this elegiac text, Couperin’s musical setting was not without a hint of satire. It was written in a vernacular style found in a collection among many airs à boire (drinking songs), including another one of his salaciously entitled “L’épouse entre deux draps” (The Wife between Two Sheets).[10] Mixing genres and registers, the “agioteurs” canon thus provides both a musical portrayal of the volatile experience of frantic stockjobbers and a lighthearted jab at the folly of stockjobbery. This creative strategy certainly brings to mind examples of visual and literary ephemera thematizing the financial bubbles in the print collection Het groote Tafereel de Dwaasheid (The Great Mirror of Folly),[11] and with his canon Couperin, more than revealing a largely hidden side of himself as a humorist, joins the chroniclers, ballad writers, and printmakers of his time in preserving a collective memory of the speculative mania.

By 1720, speculative fervor and the news of both bubbles spread widely, and conceivably reached Frankfurt. Here, booming trading businesses were conducted by the Börse. Originally used to designate specifically the Frankfurt meeting for an assembly of merchants and traders, the word Börse now simply means “stock exchange” in modern German. This assembly had occupied the ground floor of Haus Braunfels on Liebfrauenberg since 1695 (Fig. 2). The Braunfels house itself was owned by the Frauenstein association, an influential local Stubengesellschaft, or parlor society, made up of groups of wealthy merchants and university graduates including members of the Börse. Living in an upper corner of the Braunfels house was the composer Georg Philipp Telemann. More than a tenant, Telemann served as the administrator and treasurer of several charities associated with the Frauenstein society and frequently organized social functions for them.

An orchestral suite (TWV 55:B11 in B-flat major[12]) Telemann composed during the heady days of 1720 was believed to have been commissioned by members of the Frauenstein Society and the Börse.[13] Several twentieth-century Telemann scholars have made conjectural connections of the suite to various developments in the financial crisis in Paris.[14] Adolf Hoffmann, for one, gave the suite the French appellation “La bourse” and added programmatic titles for its movements: “Le repos interrompu” (Interrupted Rest), “La guerre en la paix” (War in Peacetime), “Les vainquers vaincus” (Victors Vanquished), “La solitude associée” (Communal Solitude), and the finale, “L’espérance de Mississippi” (Hope for the Mississippi). These wittily oxymoronic titles give the suite a narrative arc that transforms the 1720 bubble into an audible history. In capturing the social, political, and psychological experiences associated with speculation, these titles provide a tantalizing suggestion of listening to Telemann’s suite as a sonic encapsulation of the “projecting age”—as Daniel Defoe calls it— shaped by the financial revolution.[15]

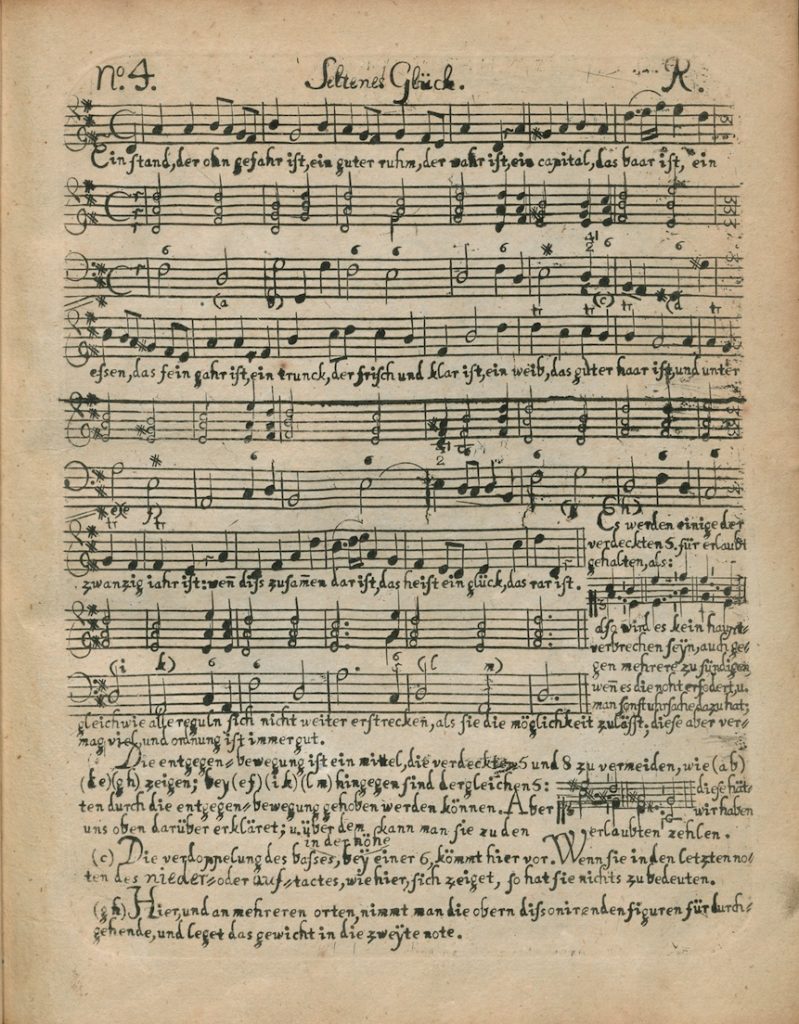

Unlike Couperin’s canon, Telemann himself did not give his suite a title or directly reference any connections to contemporaneous market events. He was, however, well aware of the appeal of using money as a musical topic. A decade later, Telemann would publish a weekly music column for the Hamburg press, each consisting of an aria and a recitative with continuo accompaniment appended with instructional advice on keyboard thoroughbass playing. These pieces, later compiled into Singe-, Spiel- und Generalbassübungen,[16] were musical offerings for the rising middle class who were keen to dabble in domestic music-making and were, as was advertised in 1733, meant to be “delightful and at the same time instructive.”[17] To delight its commercially minded readership, money frequently appears as the topic of such weekly ditties. The second song in the collection, “Geld”[18] (Money), for one, captures “the art of moneymaking” in a restless, nimble gigue. With a selective eye on the poems he would set to music, Telemann seized this publishing opportunity not only to teach music but to reflect, through his characteristic wit and humor, on the relatively new, commercial, and urban life experience brought about by modern finance. Take the fourth song “Seltenes Glück”[19] (Rare Luck), for example (Fig. 3). It exposes the transience and futility of paper wealth, among other things, and throws into relief such ideas as risk, uncertainty, and volatility that were particularly salient when lessons from the financial bubbles were still fresh.

Ein Stand, der ohn Gefahr ist,

ein guter Ruhm, der wahr ist,

ein Capital, das baar ist,

ein Essen, das fein gahr ist,

ein Trunck, der frisch und klar ist,

ein Weib, das guter Haar ist.

und unter zwanzig jahr ist,

wenn diß zusammen dar ist,

das heist ein Glück, dar rar ist.

[A standing that is without threat,

a good reputation that is true,

a capital that is ready money,

a meal that is well made,

a drink that is fresh and clear,

a woman with a good head of hair,

and under twenty years of age:

when all of these are combined,

it adds up to luck that is rare.]

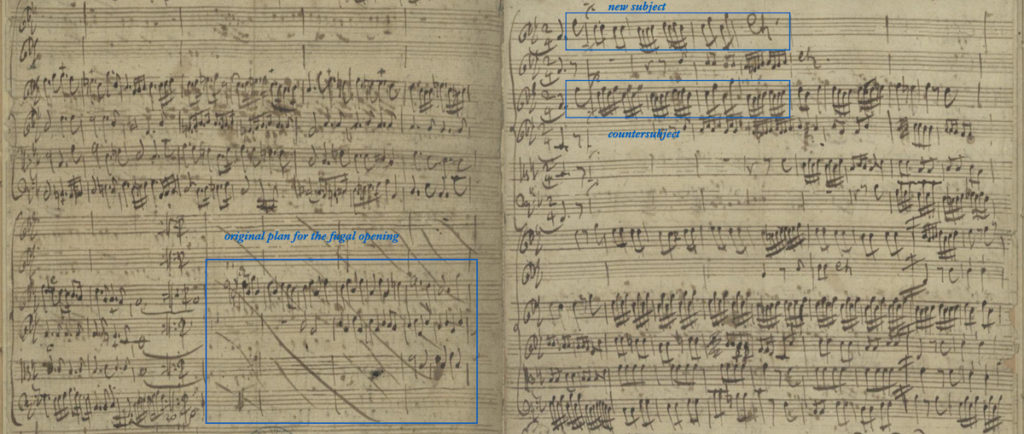

Given Telemann’s multiple associations with market-themed music and his stock-trading neighbors, it is little wonder that scholars would be tempted to give the B-flat suite the famous appellation “La bourse.” Such biographic speculations also led to colorful and imaginative hermeneutic exercises. Adolf Hoffmann, for one, has suggested that the opening movement in particular depicts “the pride and certainty of the stockholders.”[20] Perhaps one could venture even further.[21] While the regal French overture sections that frame this movement certainly lend a character of “pride and certainty,” it is the fugal section in the middle that seems to depict the dangerous exuberance of market speculation with its contrasting musical textures, daring harmonic shifts, and inventive orchestration. If one takes a look at the manuscript (Fig. 4), Telemann’s original design of the fugue had a jagged subject—the main melodic theme of the movement—made of long notes (mostly quarters) moving in a deliberate and unhurried pace. It was crossed out almost immediately and replaced with a new version: high-spirited and high-octane. The new and faster-moving subject (mostly in eighth notes) is further enlivened by a countersubject moving twice as fast (in sixteenth notes), their combination replicated seamlessly in alternating permutations of voices. Such a design gives the impression of restlessness, like an automaton churning out counterpoint with its whirling cogs and gears. If one could hear and interpret the proliferating counterpoint in the fugal exposition as the scurrying stockjobbers going about trading and bidding,[22] then the modulating sequence braving an unpredictable path of harmonic excursion in the middle of the fugue might be thought of as mirroring the precarity of quick money. Equal parts exciting and nervous, this music would have resonated with Telemann’s financially inclined neighbors when performed at one of those soirées the composer organized. A social lubricant, music in the time of the 1720 bubbles cast its imaginative impact on the bourgeoning financial market by giving it a sensuous shape that both stoked the fantasies of the speculators and incited the suspicions of their detractors. In so doing, such eighteenth-century market music reveals to us that monetary interests and aesthetic ones—their distinctions routinely invoked in today’s political and scholarly habitats—were mutually engendering in those early days of financial capitalism.

Morton Wan is a PhD candidate in musicology at Cornell University

[1] Richard Steele, The Theatre, by Sir Richard Steele; to Which Are Added, The Anti-Theatre (London, 1791), 149.

[2] See Judith Milhous and Robert D. Hume, “The Charter for the Royal Academy of Music,” Music & Letters 67:1 (1986), 50–58.

[3] Winton Dean and John Merrill Knapp, “Radamisto,” in Handel’s Operas, 1704-1726 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 324-367.

[4] Winton Dean, “Baldassari, Benedetto,” Grove Music Online, accessed 14 Dec 2019: https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.01849.

[5] Aria “Deh, fuggi un traditore” from Handel, Radamisto, by Il Complesso Barocco, conducted by Alan Curtis (Virgin Classics, 2004): https://open.spotify.com/track/2RLUCk9pZKxaAyavrmfAYj?si=B_lHEPbpRrK3A9hR-XttHA.

[6] For a classic example of critical views of Italian opera in London, see Joseph Addison, “From The Spectator, Tuesday, March 6, 1711,” cited in Oliver Strunk, ed., Source Readings in Music History (New York: W. W. Norton, 1950), 511-517.

[7] Greer Garden, “Un canon à cinq inédit de Couperin,” Bulletin de l’Atelier d’études sur la musique française des XVIIe & XVIIIe siècles 10 (February 2001), 16–17.

[8] Graham Sadler, “A Philosophy Lesson with Francois Couperin? Notes on a Newly Discovered Canon,” Early Music 32:4 (2004), 541–547.

[9] I thank Frederick Cruz Nowell for assisting with this translation and for bringing to my attention “the weight of sin” connoted by such words as “aveux” and “néant,” as well as connections between theology and finance: on this topic, see Charly Coleman, The Spirit of French Capitalism: Economic Theology in the Age of Enlightenment (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2021).

[10] Green, “Un Canon,” 16.

[11] William N. Goetzmann et al., eds., The Great Mirror of Folly: Finance, Culture, and the Crash of 1720 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

[12] La Bourse Suite in B-flat major from Telemann, Orchestral Suites, by Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra (Analekta, 1999): https://open.spotify.com/track/4eIh5R5yFNrASjJW0FEN2U?si=APZeSAKAQ3SWsq7wcqKNkQ.

[13] Alfred Hoffmann, Die Orchestersuiten Georg Philipp Telemanns: TWV 55 (Wolfenbüttel: Möseler, 1969), 17. Also see Steven Zohn, Music for a Mixed Taste: Style, Genre, and Meaning in Telemann’s Instrumental Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 105-108.

[14] Besides Hoffmann, see also Michael Philipp, Läppische Schildereyen? Untersuchungen zur Konzeption von Programmusik im 18. Jahrhundert (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1998).

[15] In his well-known 1697 “Essay upon Projects,” Daniel Defoe tried to make a case for the “projectors and projects,” the eighteenth-century buzzwords for entrepreneurs and enterprises, by outlining the social changes that could be brought about by joint-stock projects in Britain’s new capital market. For a discussion of Defoe’s essay, see Jon Klancher, “From the Age of Projects to the Age of Institutions,” in Transfiguring the Arts and Sciences: Knowledge and Cultural Institutions in the Romantic Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 30-33.

[16] Georg Philipp Telemann, Singe-, Spiel- und Generalbassübungen (Hamburg: Composer, 1733-1734); a facsimile copy can be found on IMSLP: https://imslp.org/wiki/Singe-%2C_Spiel-_und_Generalbassübungen%2C_TWV_25:39-85_(Telemann%2C_Georg_Philipp).

[17] Hamburgische Berichte von neuen gelehrten Sachen 2:88 (November 3, 1733). See also the discussion of the rising subscription price and commercial success of Telemann’s Singe-, Spiel- und Generalbassübungen in Brian Douglas Stewart, Georg Philipp Telemann in Hamburg: Social and Cultural Background and Its Musical Expression (PhD dissertation, Stanford University, 1985), 127-128.

[18] “Geld,” from Telemann, Singe-, Spiel- und Generalbassübungen, by Klaus Mertens and Ludger Rémy (CPO, 2006): https://open.spotify.com/track/2Vwz47ge21j61O8X0udTGL?si=qdeOf45iRESauK5syMPyeQ.

[19] “Seltenes Glück,” from Telemann, Singe-, Spiel- und Generalbassübungen (see n. 16).

[20] Hoffmann, Die Orchestersuiten,17.

[21] For a fuller market-inspired interpretation of Telemann’s suite and the Mississippi Bubble, and a wondrous inspiration for the present essay, see David Yearsley, “Market Music,” Counterpunch (February 23, 2018): https://www.counterpunch.org/2018/02/23/market-music/.

[22] For a technical account of stock-jobbery in the eighteenth-century, see Thomas Mortimer, Every man his own broker; or, A guide to Exchange-Alley (London, 1769); for an analysis of trading activities in the coffee houses, see Edward Stringham, “The Emergence of the London Stock Exchange as a Self-Policing Club,” Journal of Private Enterprise 17:2 (2002), 1–19.

Cite this note as: Morton Wan, “Music in the Time of Bubbles: Sounding the Market in London, Paris, and Frankfurt,” Journal18 (January 2021), https://www.journal18.org/5472.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.