The Palace of Versailles remains a subject of interest and fascination for scholars and curators alike. Recent exhibitions and publications reveal that there are still new angles to explore of this already much-studied seat and symbol of power. The Versailles Effect: Objects, Lives, and Afterlives of the Domaine (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020) is one of the latest additions to the bibliography. Edited by Mark Ledbury and Robert Wellington, the collection of essays is based on papers presented at an international conference at the National Gallery in Canberra. Held in 2016, the conference was concurrent with the exhibition Versailles: Treasures from the Palace, jointly organized by The Palace of Versailles and the National Gallery of Australia. As Melissa Hyde, Professor of Art History and Distinguished Teaching Scholar at the University of Florida, wrote in a review, this new anthology illustrates that “Versailles was more than the magnificent palace of the Sun King. It was a domain, cultural, artistic, political; an experience, and an idea, whose power, meanings, and effects still resonate today.”

During the ancien régime, Versailles attracted diplomats and embassies from Europe and all over the world. Contemporary accounts illustrate how these foreign visitors, some of whom remained in France for multiple years, were confronted by political, cultural, and religious matters—among them Louis XIV’s 1685 Revocation of the Edict of Nantes—that they needed to negotiate. The research presented here emerged from archival study undertaken for both the Canberra Conference and the Visitors to Versailles exhibition held in 2017-2018 at Versailles and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. It concerns issues of religious expression and the ceremonial display of tapestries—not on the interior walls of Versailles but rather outdoors, on the streets of Paris, where many of these diplomats lived.

On June 13, 1721, Cornelis Hop (1685–1762), Dutch ambassador in France, wrote the following message to François Fagel (1659–1746), secretary to the States General (the representative body of the Seven Provinces constituting the de facto federal government of the Dutch Republic): [1]

This time the preparations for the Corpus Christi Day procession went in a decent manner. The Commissioner of the neighborhood came to ask me eight or ten days ago if I would permit the hanging of tapestries from the walls of my house… [2]

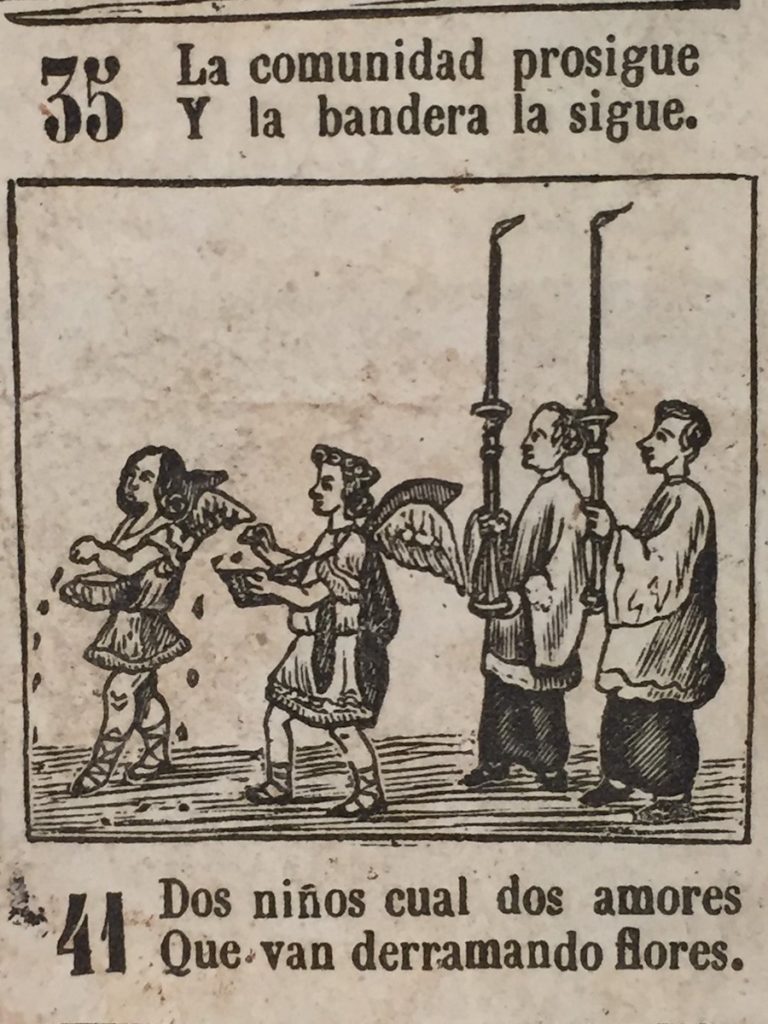

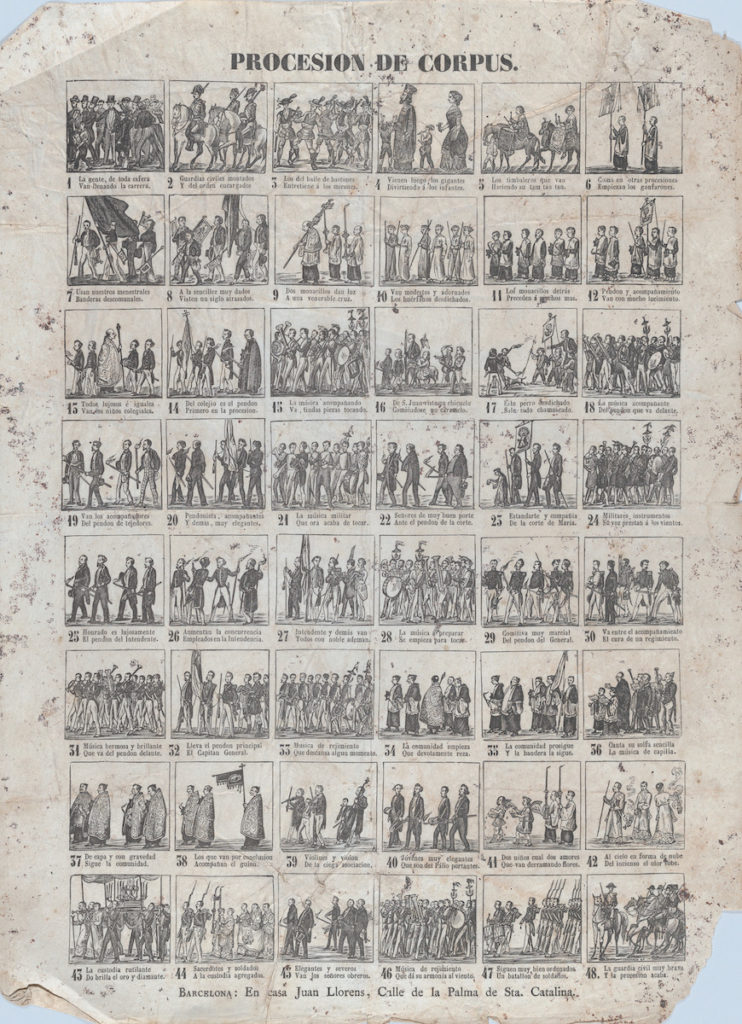

Since the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, tapestries had brought color and decoration to noble and wealthy households and had offered protection against drafts.[3] The best sets were reserved for special occasions and were even taken outdoors for public display during important secular and religious events, as was the case with the annual feast of Corpus Christi.[4] The feast’s observance dates to 1264, when Urban IV (1195–1264) issued a Papal bull instituting it as a universal feast of the Roman Catholic Church commemorating the transubstantiation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ.[5] Traditionally observed on the Thursday in late May or early June following Trinity Sunday, Corpus Christi (or Fête Dieu in French) was, from the fourteenth century onward, celebrated with a procession after Mass (Fig. 1).[6] For outdoor celebrations, streets were specially cleaned and strewn with sand or sawdust and greenery to guard against slippery conditions, while children scattered flowers along the way (Fig. 2).[7] As on days of the grandest secular ceremonies and triumphal entries, textiles lined the processional route, transforming the streets into ritualized space.[8]

Although frequent handling, moving, and exposure to the elements are detrimental to the wellbeing of tapestries, some of these processional hangings survive. A Flemish example depicting the Mystery of the Eucharist preserved in the Cathedral of Saint Vincent in Chalon-sur-Saône, France, is a good example (Fig. 3). Dating to about 1500, the weaving allegedly embellished the nearby residence of Hugues Baichet, a procureur du Roi (public prosecutor) during the annual Corpus Christi procession. The textile would have concealed the lower part of the façade, but the architectural elements woven into its design—bases, pilasters, and entablature—are reminiscent of triumphal arches, which since antiquity were permanently or temporarily constructed for ceremonial entries into cities.[9] Divided into two tiers, possibly meant to conform to two stories of the Baichet house, the tapestry consists of multiple scenes punctuated by the device Spes mea Deus (God is my hope). Its registers depict Biblical stories from the Old and New Testaments that foreshadow or symbolize the Eucharist, framed by pilasters with Renaissance ornament.[10] One of the temporary altars, which were placed at regular intervals along the processional route, could be positioned in front of the hanging, thereby turning the textile into a retable, as is still done at the Cathedral of Saint Vincent. The tradition of decorating the streets on religious holidays also continues today, perhaps most notably in Toledo, Spain.[11] A set of six Flemish tapestries depicting subjects from the Triumph of the Eucharist, woven by Jan-Frans van den Hecke (active after 1660–d. 1695), is still hung on the exterior walls of the city’s cathedral on Corpus Christi day.[12]

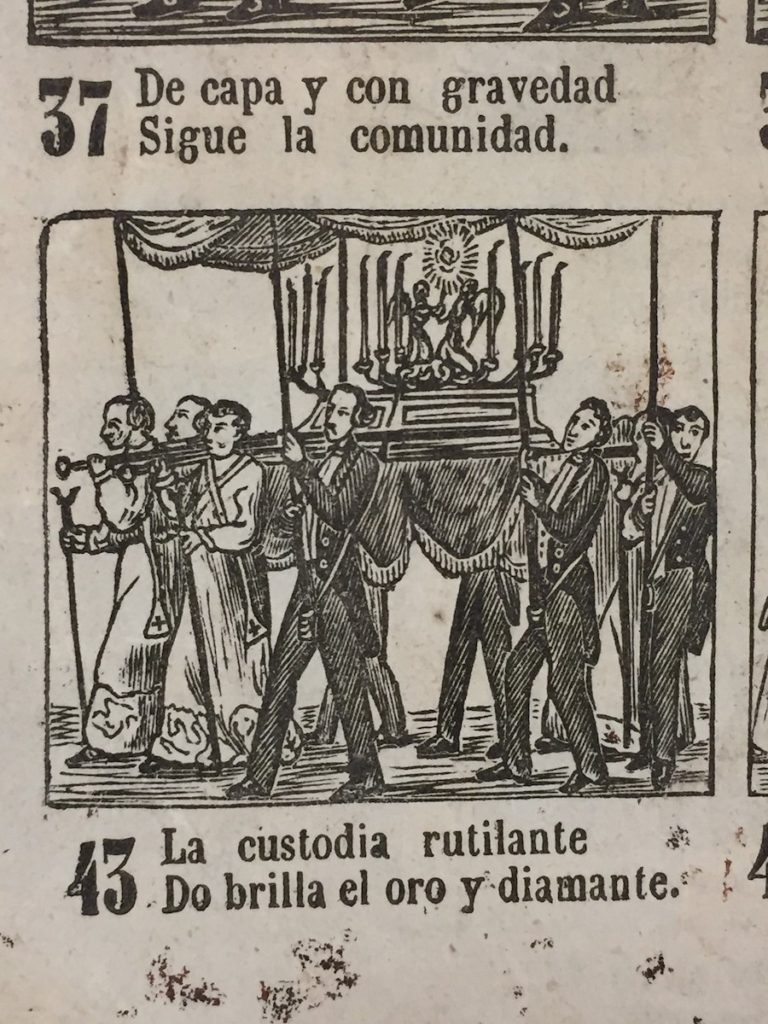

By the eve of the Reformation, the importance of the festival had surpassed that of Easter celebrations.[13] When Protestant reformers began to dispute the doctrine of the transubstantiation, the third Council of Trent (1551–1552) issued a decree confirming that Christ was present in both the consecrated bread and wine. This only reinforced Catholic belief in transubstantiation during the Counter-Reformation and further added to the significance of the feast.[14] The consecrated Host, carried respectfully under a canopy for all to witness, served as a symbol of the presence of Christ, while the procession constituted a public affirmation of faith (Fig. 4).[15]

The spectacle of clergy dressed in their finest vestments carrying banners, crosses, and candles and followed by hundreds of lay participants was very impressive, especially for Protestant spectators who were not used to such religious manifestations (Fig. 5). Having witnessed the Corpus Christi procession in Tours, British diarist John Evelyn (1620–1706) observed in 1644:

[It] was the Fête Dieu, and a goodly procession of all the religious orders, the whole streets hung with their best tapestries, and their most precious movables exposed; silks, damasks, velvets, plate, and pictures in abundance; the streets strewed with flowers, and full of pageantry, banners, and bravery.[16]

Early eighteenth-century diplomatic dispatches illustrate that the orchestration of the tapestry display for the Corpus Christi celebration in Paris did not always happen without incident. Hop, scion of a prominent Amsterdam family, was named resident ambassador to France in March 1718, a position he held until 1725.[17] As the representative of a Protestant nation serving in France (where Huguenots, since the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, were not allowed to openly practice their religion and were at risk of persecution), Hop was in the minority and regularly at odds with his host government. The Dutch diplomat frequently consulted with both the British ambassador, John Dalrymple, second Earl of Stair (1673–1747) and the Swedish representative, Count Eric Sparre (1665–1726), about sensitive religious issues. Their three embassies housed chapels where Protestant services were held on a weekly basis. When the sermons were given in French rather than in Dutch, there was objection from the French government out of fear that these services would attract Huguenots. From time to time the authorities arrested some of the faithful who worshipped at Hop’s chapel. The diplomat would intervene on their behalf at court and usually managed to get them released after a few days.[18] It is no wonder, then, that Hop was wary the day before Corpus Christi (he referred to it as Sacrament’s Day), when the stoop in front of his house (also serving as the embassy) was measured without his being asked. In a dispatch addressed to secretary Fagel of June 9, 1719, he wrote:

Yesterday around five o’clock in the afternoon, several people came to measure the distance from the wall which separates the courtyard [in front] of my house from the street. They did this without introducing themselves or explaining what their purpose was. Since tomorrow it will be the feast of the Eucharist when the Roman Catholics decorate the streets with their best hangings and furniture, I got the suspicion that the parish priest or another fanatic would secretly hang some tapestries, realizing that this would not happen at my initiative. I ordered my manservant to be vigilant and that if someone would arrive with the intention of displaying tapestries to prevent him from doing so without giving [him] another reason other than that I could not allow [him to do this] without having received my permission.[19]

Hop’s suspicions were correct, because early the next morning a wagon arrived loaded with tapestries to be nailed to the wall in front of his house. Unfortunately, the dispatch does not mention the subjects of these hangings or where they came from.[20] The diplomat refused to give his consent and several hours later the commissioner of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, where Hop rented a house, stopped by in an earnest effort to change Hop’s mind. The commissioner was unable to speak to the ambassador, since Hop had given his staff orders not to disturb him before he was awake. He was notified, however, that the diplomat was displeased that an attempt had been made to attach the tapestries without first asking permission. Hop also wrote to the British ambassador, hoping that the Earl of Stair, who had served in Paris longer than he, might be able to inform him about common practice in this situation. The British diplomat thought that his colleague was under no circumstances obliged to permit the display of tapestries, which Hop ultimately did not allow. The dispatch informs us that the procession passed by Hop’s residence without incident; the entrance gate and the windows of his house remained closed and none of his servants watched the spectacle from the street.[21] The story did not end there—further reports to Secretary Fagel indicate that Hop’s refusal to participate on Corpus Christi reached higher circles.

Exactly a week later, on June 16, Hop described in detail that he went to court on the previous Tuesday (Tuesdays being the day that the foreign ambassadors were received at the Tuileries Palace to pay their respects to the king).[22] On that occasion, he was approached by Abbé Guillaume Dubois (1656–1723), adviser and envoy for foreign affairs to Philippe II duc d’Orléans (1674–1723), who was regent to the young Louis XV (1710–1774). Dubois showed the Dutch diplomat a declaration from the commissioner of the Faubourg Saint-Germain stating that it had always been the practice of Protestant ambassadors to allow the display of tapestries on days of processions. Hop was requested to cooperate the following Thursday, on the Octave of the holiday, when a procession would once more pass by his house.[23] He consulted again with the Earl of Stair, even though the home of the British ambassador was not on the traditional processional route. Both representatives agreed that “our residences being those of our sovereigns should not be embellished for a ceremony honoring a religion which is not theirs.”[24] Hop furthermore asserted that the reasoning of the commissioner was not applicable to his situation. In his declaration the official referred to a hôtel garni (a boarding house or furnished residence) belonging to a French subject who was required to follow local regulations. Hop argued that his having rented an empty townhouse furnished at his own expense should relieve him of the duty to adorn its walls with hangings.

The Dutch diplomat was called to meet with the regent, who deferred to the commissioner’s declaration. The Duke of Orléans pointed out that Hop might be in danger of maltreatment by zealots who considered his refusal to participate as disrespectful to their religion. Unperturbed, the ambassador stuck to his decision but proposed a convenient and diplomatic solution, ultimately appeasing both sides. The tapestries would be attached to wooden posts placed several feet in front of Hop’s residence, thereby asserting the building’s (and Hop’s) neutrality.[25] The commissioner, notified of this decision, told Hop that he had collected in great haste a few poles and that he was sorry not to have more time to find a larger number. Hop recounted that the hangings were affixed to these posts for as much as they could stretch and were further fastened to the wall of his garden.

This concession was repeated in subsequent years, and no further problems regarding the display of tapestries were reported during the remainder of Hop’s tenure in Paris. Instead, the Dutch representative shared in later dispatches that Louis XV spent part of the time in devotion now in this church and then in another during the eight-day observance of Corpus Christi in 1721.[26] The following year the diplomat described that the French king and his entire court joined the procession on foot at the Tuileries Palace.[27] Bridging religious differences without compromising allegiance to his Protestant nation or interrupting the display of textiles along the processional route, Hop’s clever compromise proved that diplomacy can save the day.

Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide is Henry R. Kravis Curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, NY

[1] François succeeded his father Hendrik Fagel in this position. G. Waterhouse, “The Family of Fagel,” Hermathena 21:46 (1931), 83.

[2] See Hop’s report of June 13, 1721. National Archives The Hague, Netherlands [henceforth NL-HaNA,] Hop, 1.10.97, inv.nr. 64.

[3] Thomas P. Campbell, Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002), 22–23.

[4] Bernard Guenée and Françoise Lehoux, Les entrées royales françaises de 1328 à 1515, Sources d’Histoire Médiévale 5 (Paris, 1968), 18, 70, 188. Quoted in Adolfo Salvatore Cavallo, Medieval Tapestries in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993), 29, 31.

[5] Miri Rubin, Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1991), 176–177. See also Edward Muir, Ritual in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997), 148–149.

[6] Rubin, Corpus Christi, 243–271. See also Teofilo F. Ruiz, A King Travels: Festive Traditions in Late Medieval and Early Modern Spain (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 2012), 269.

[7] This greenery is reminiscent of the palm branches on Palm Sunday. Neil Murphy, “Building a New Jerusalem in Renaissance France: Ceremonial Entries and the Transformation of the Urban Fabric, 1460-1600,” in Katrina Gulliver and Heléna Tóth, eds., Cityscapes in History: Creating the Urban Experience (London: Routledge, 2014), 183–185. See also Rubin, Corpus Christi, 248.

[8] Murphy, “Building a New Jerusalem,” 185.

[9] Richard Cooper, “Court Festival and Triumphal Entries under Henri II,” in J.R. Mulryne and Elizabeth Goldring, eds., Court Festivals of the European Renaissance: Art, Politics and Performance (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), 51–75.

[10] (Left upper panel) Melchizedek offers Abraham bread and wine (Genesis 14:18); (Left lower panel) Manna from Heaven for the Children of Israel (Exodus 16: 14–15); (Right upper panel) Last Supper (Luke 22: 7–23); (Right lower panel) Passover (Exodus 12:21). (Center upper panel): Altar with Holy Sacrament flanked by angels and donors presumably members of the Baichet family.

[11] Online videos document the procession filmed in recent years.

[12] Nora de Poorter, “The Triumph of the Eucharist,” in Guy Delmarcel et al., Rubens’s Textiles, exh. cat. (Antwerp: Luc Denys, 1997), 87–88, fig. 27.

[13] Philip M. Soergel, Wondrous in His Saints: Counter-Reformation Propaganda in Bavaria (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1993), 81.

[14] Britannica Academic, “Council of Trent,” accessed September 23, 2019, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Council-of-Trent/73300.

[15] Ruiz, A King Travels, 269. See also Muir, Ritual in Early Modern Europe, 69.

[16] May 25, 1644. William Bray, ed., The Diary of John Evelyn, 2 vols. (New York and London: Walter Dunne Publisher, 1901), 1:71.

[17] P.J. Blok, P.C. Molhuysen, Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek 2 (1912), column 602, entry by C.H.Th. Bussemaker. See also Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide, “Cornelis Hop (1685–1762), Dutch Ambassador to the Court of Louis XV,” in Mark Ledbury and Robert Wellington, eds., The Versailles Effect: Objects, Lives, and Afterlives of the Domain (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020), 193-212.

[18] See Hop’s reports of August 26, 1720; July 4 and 7, 1721; and October 6, 1721. NL-HaNA, Hop, 1.10.97, inv.nr. 64.

[19] Hop’s report of June 9, 1719. NL-HaNA, Hop, 110.97, inv.nr. 64.

[20] The tapestries could have been rented, loaned, or requisitioned, as happened with textiles used for ceremonial entries. Murphy, “Building a New Jerusalem,” 185.

[21] Hop’s report of June 9, 1719. NL-HaNA, Hop, 110.97, inv.nr. 64.

[22] Following the 1715 death of Louis XIV, the court moved from Versailles back to Paris with the young king residing in the Tuileries Palace. Louis XV remained in Paris until 1722 when he relocated the court back to Versailles.

[23] The Octave is the actual feast day and the seven days following it–here the last day of the festival.

[24] Hop’s report of June 16, 1719. NL-HaNA, Hop, 1.10.97, inv.nr. 64.

[25] This was apparently done elsewhere in the city and at the Tuileries Palace. Hop’s reports of June 9 and 16, 1719; April 29, 1720; and June 13, 1721. NL-HaNA, Hop, 1.10.97, inv.nr. 64.

[26] Hop’s reports of June 13, 1721 and June 10(?), 1721. NL-HaNA, Hop, 110.97, inv.nr. 64.

[27] Hop’s report of June 5, 1722. NL-HaNA, Hop, 110.97, inv.nr. 64.

Cite this note as: Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide, “To Display Tapestries on Corpus Christi or Not: Finding a Compromise,'” Journal18 (February 2021), https://www.journal18.org/5509.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.