Jardins, Grand Palais, Paris, 15 March–24 July 2017. Curated by: Laurent Le Bon, Marc Jeanson, and Coline Zellal.

As the site of productive and often intriguing interactions between art and science, nature and artifice, the garden is an alluring subject, all the more so given the pervasive cross-disciplinary thinking in our current academic climate. Yet as historians of art, landscape architecture, and science know all too well, the garden can be complicated and unwieldy. Gardens have proven especially challenging for museums, and in the last five years a series of exhibitions in Europe have offered various approaches to presenting the garden within the confines of a gallery. Of particular note are shows in Versailles, London, and Paris where the curators proposed monographic, thematic, or single-medium approaches to the garden.[1] This summer’s Jardins exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris, however, takes a broader perspective on the topic—defining the garden as an enclosed, staged space that mirrors the world. In its geographical and temporal parameters, the exhibition is similarly vast: focusing (although the title does not acknowledge it) on the West, and on France in particular, from the sixteenth century to the present. From this expansive chronology, the curators have assembled a staggering collection of objects installed over two floors that range in media from books to film, ceramics to glass, wall painting to canvas, wax, and paper, and even precious stones and organic specimens.

Such a broad approach raises a seemingly contradictory question: How does one display the garden in the space of a cultural institution like the art museum? In response, the Grand Palais has proposed an exhibition that draws parallels between the circumscribed and mediated space of the garden and that of the museum, where the garden is present only at the level of representation. Consequently the galleries are organized thematically according to principles of garden organization or design: botany, allée, perspective, and bosquet. The structure of Jardins, however, does not follow the internal logic and cohesive plan of a formal garden. Instead, in its fragmented presentation of objects, the exhibition more closely resembles a florilegium, a bound collection of botanical specimens and illustrations found alongside garden manuals and naturalist texts in many libraries of eighteenth-century amateurs and curiosity collectors.

Like a florilegium, the exhibition stages several fascinating encounters between art and science. That gardening is an art and the garden a work of artifice—subjected to the rules of architecture, design, and, at times, painting and therefore the product of human intervention into the natural world—is commonplace. The natural sciences too have always existed in the garden. For example, physicians collaborated with botanists in medicinal gardens, hydraulics experts worked to realize the designs of garden architects, and artists teamed up with naturalists to illustrate botanical and garden manuals. While the relationship between art and science in gardens is well-trodden territory, Jardins offers new perspectives on the topic in part by exhibiting a series of truly extraordinary objects, some of which will be familiar to art historians. Albrecht Dürer’s watercolor Madonna of the Animals (1503) is one example: an otherwise traditional devotional image animated with meticulous renderings of plants and animals that herald the advent of modern scientific illustration. Other works present familiar subjects but in novel ways, as in a 1718 plan of the gardens of Versailles by Denis Le Fils. It superimposes upon the patterned parterres and bosquets the chaotic network of lead and iron pipes that fed the garden’s water features—a scientific and technical achievement that is all too often ignored. There are, additionally, objects that stand out simply because they are so rarely on public display, including Carmontelle’s painted transparency Les Quatre Saisons (1798), shown backlit as the artist intended—a superb example, moreover, of the exhibition’s presentation of the garden as spectacle (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Installation view of Louis Carrogis (called Carmontelle)’s Les Quatre Saisons (1798). Musée du Domaine départemental de Sceaux, Sceaux. Photo: Matthew Gin.

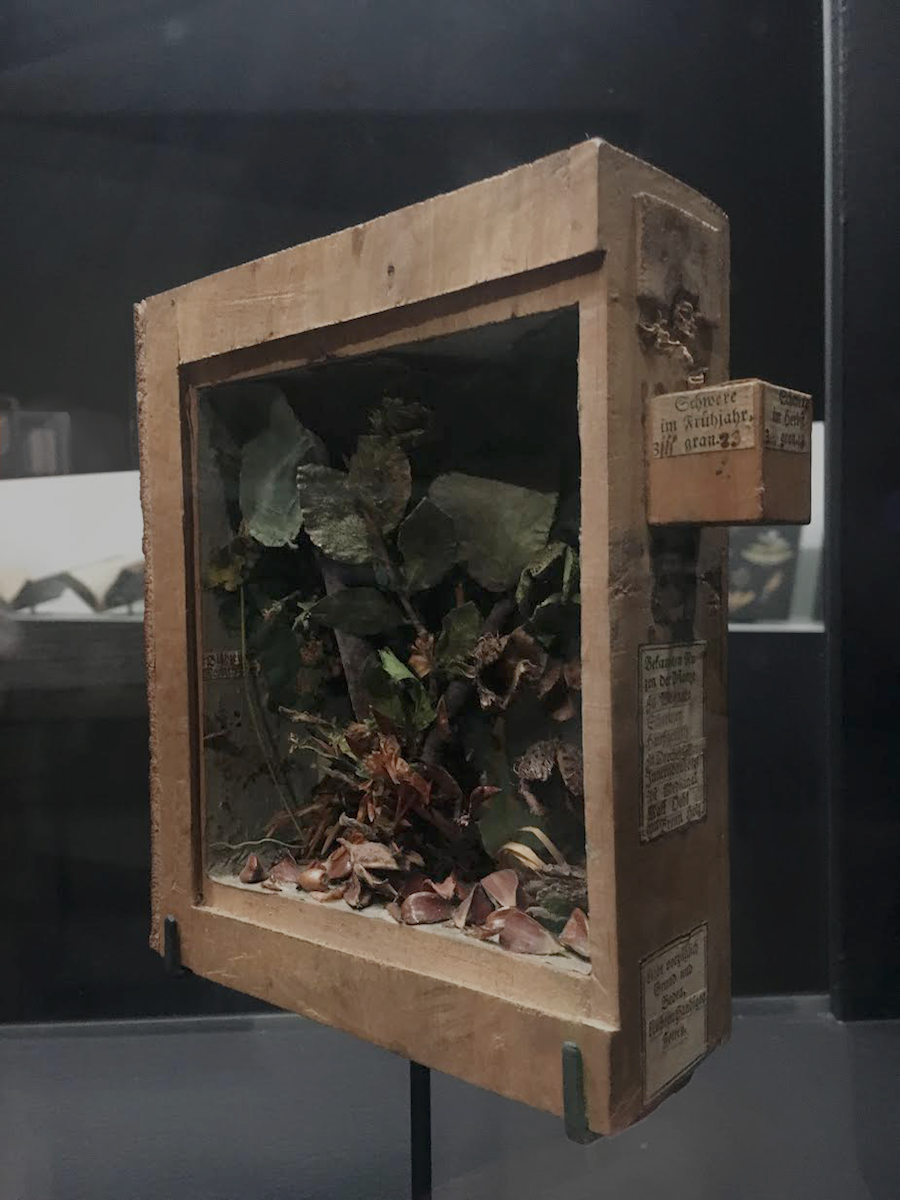

Perhaps most remarkable and unfamiliar are objects that originate from the study of botany. Most of these appear in a serpentine gallery divided into three thematic sections: “Botanique,” “Arboretum,” and “Mixed Border.” Among the first items displayed are a series of film clips from La Croissance des végétaux (1929), the collaborative project of Jean Comandon, a doctor who pioneered the use of film to analyze the movement of living organisms, and Pierre de Fondbrune, a director, scientist, and inventor. La Croissance des végétaux offers an almost hypnotic study of plants in motion. Sped up to make their growth process more easily discernible, the short films show dandelions bursting open and the thin tendrils of a pumpkin plant reaching tentacle-like for a wooden stake. The gallery also contains a series of paper cut-outs of flowering plants by the German artist Philipp Otto Runge. Made in the first decade of the nineteenth century, these cut-outs stage a curious encounter between the art of the silhouette and botanical study. Especially noteworthy, though, is Carl Schildbach’s Fagus sylvatica L. (1771–99), an object that hybridizes the herbier with the diorama, shadow box, and book (Fig. 2). Schildbach, a German naturalist, amassed a collection of 530 arboreal specimens organized like books with a volume devoted to each specimen, of which Fagus sylvatica L. is one. Comprising a box filled with dried specimens and replicas of leaves, fruit, and flowers made of wax, its name is written on one side of the wooden “spine” or frame.

Fig. 2. Installation view of Carl Schildbach’s Fagus sylvatica L. (c. 1771–99). Naturkundmuseum im Ottoneum, Kassel. Photo: Matthew Gin.

In addition to this staggering assortment of exceptional objects, Jardins provides opportunities for more sustained and focused reflection. This is most powerfully felt in the last gallery on the first floor. Situated midway through the exhibition, the room contains only three works: Thomas Demand’s photograph Hecke (Hedge; 1996), Henri Matisse’s cut-out Acanthus (1953), and a painting by Franz Gertsch entitled Gräser I (1995–96). All three take leaves as their subject. Demand’s photograph shows a closely cropped view of leaves that the artist has meticulously and deceptively crafted from paper to resemble an actual hedge. Franz Gertsch’s Gräser I offers a photorealistic rendering of grass, while Matisse’s cut-out contains exuberantly polychromed fragments of the acanthus plant. In this spare installation, foliage is offered as a meditation on the fundamental artifice of the garden and on the role of human intervention in nature. Similarly, a gallery of photographs by Wolfgang Tillmans in the exhibition’s second half affords a moment to reflect on the garden not as a place of Edenic promise and abundance but as a space in close but uneasy proximity with humanity. The photographs stand in stark contrast to the gallery of polite drawings of eighteenth-century gardens that precede them. In Mexican non-GM corn plant, the specimen is placed in a room where it pushes uncomfortably against the walls and ceiling, while shoe (grounded) (2014) depicts a disembodied Nike sneaker trampling dead leaves and fledging blades of grass underfoot.

The exhibition’s substantial catalogue is labyrinthine and, as a result, difficult to navigate. Like the galleries themselves, the catalogue—with contributions by Hervé Brunon, Monique Mosser, and Jean-Pierre Le Dentec, among others—is organized thematically according to components of the formal garden with the text set to resemble a garden parterre. One of the more interesting contributions to the critical literature on garden history is a short essay by film curator Dominique Païni, in which he asks if it is possible to “hypothesize that the invention of film was closely associated with the scenography of the garden.”[2] The installation asks this question as well, perhaps most effectively through a clip of Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), which is shown at the end of an “allée” of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century garden plans by André Le Nôtre and others. Whereas this juxtaposition cannily suggests how the formal garden’s construction of space lends itself to the medium of film, other clips—from Edward Scissorhands to The Godfather—serve merely to animate particular moments without contributing to the exhibition’s larger narrative.

Fig. 3. Installation view of Hubert Robert’s Grotte du parc de Méréville (date unknown). Private collection. Photo: Matthew Gin.

Drawing inspiration from Greenaway’s draughtsman, a lascivious (and fictional) artist named Mr. Neville who is commissioned to produce twelve drawings of different framed views of an aristocratic English estate, the exhibition’s curators constructed a temporary wall with rectangular “windows,” behind which were exhibited such paintings as Jean-Antoine Watteau’s Assemblée dans un parc (c. 1716–17) and Hubert Robert’s Grotte du parc de Méréville (undated) (Fig. 3). Here the intended effect of framing the visitor’s visual experience does not work. Instead, the viewer finds him/herself trying to peer through the windows in order to see the entirety of the paintings’ compositions.

The garden is complex, amorphous, and ephemeral. Any attempt to present all—or even some—of its facets is an ambitious one. Jardins is filled with incredible objects and impressive loans, but the tendency to cluster types of objects in repetitive multiples means that many works are easily overlooked. Instead of a wall of herbiers or a gallery of eighteenth-century French landscape paintings, what if the approach were chronological—built around time and moments in artistic and scientific history—rather than loosely thematic? Is there not much to be gained from seeing Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s Fête à Saint-Cloud (1775–80) alongside Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s herbier (1769–70), the latter a documentation of plant specimens from a trip to southern France? We are left to imagine the productive dialogue that would ensue from exhibiting Dürer’s watercolors of a clump of grass (mid-1490s) in the vicinity of Bernard Palissy’s terracotta grotto fragments (second half of the sixteenth century). A chronological presentation, one organized across swaths of time rather than media, would have presented not just highlights from the histories of art and science, but something of the thought patterns that led to the intermingling of those histories.

Lauren R. Cannady is assistant director of the Research and Academic Program at the Clark Art Institute and Matthew Gin is a PhD candidate in the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University

[1] André Le Nôtre en Perspectives, 1613-2013 (Versailles: Château de Versailles, 2013); Painting Paradise: The Art of the Garden (London: Royal Collection, 2015); Au-delà des étoiles: Le paysage mystique de Monet à Kandinsky (Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2017).

[2] “Peut-on faire l’hypothèse que l’invention du cinéma s’associa étroitement à la scénographie jardinière?” Dominique Païni, “Jardins en mouvement,” in Laurent Le Bon, Marc Jeanson, and Coline Zellal, eds., Jardins (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2017): 248-49.

Cite this note as: Lauren R. Cannady and Matthew Gin, “Nature Abundant: “Jardins” at the Grand Palais,” Journal18 (July 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1877

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.